Gone After Dinner

Marcelli's Italian Restaurant shuts down

By Jennifer Fumiko Cahill [email protected] @jfumikocahill[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Cork-down wine bottle chandeliers light Marcelli's Italian Restaurant from the chipped green linoleum counter on one side to the corner that was once walled off during the spot's time as an Italian deli but is now decorated with framed news articles. Outside the front windows, cars flash by on Fifth Street's three lanes as a tall grim-faced man makes his way out of the shop and down the sidewalk with a 2-foot stack of ravioli and take-out boxes. A few regulars cheerfully hassle another man coming through the door.

"You're not welcome here," one calls, earning a smile and wave from the man.

The server adds, "Actually, we're closed," and he buys it just for a second before everyone breaks out laughing.

It's Thursday, Jan. 2, and the small restaurant run by the family that's been making ravioli in Eureka for 90 years will close for good the following day after dinner service. While the ravioli will still be made in the back and shipped to stores for at least a little while, long time customers and curious newcomers are ordering boxes at the register before they're gone.

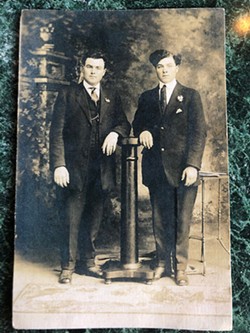

The ravioli — soft 1-inch squares of white durum wheat dough filled with finely ground meat or cheese — and the accompanying containers of sauce are made according to the same recipe Attilio Marcelli used when he started making it in 1911. According to family research, Marcelli immigrated from Olivola, Italy, a northern town between Milan, Genoa and Turin, through New York's Ellis Island in 1909 on a ship named The Chicago. From there, they say he traveled to Pennsylvania and eventually California, landing in Eureka and partnering on a ravioli factory with two other men. According to family lore, when the partners offered to buy him out at a lowball price, he countered and bought their shares. Eventually Attilio Marcelli's sons, Gino and Danny, took over the factory, which moved to Third and G streets around 1927. (This meant passing into the "North of Fourth" zone from which Italians were banned during World War II due to proximity to the harbor and fear of spying or sabotage, but, according to the family, the local police knew Attilio and let him pass.) When Danny left, Gino ran it with his son Angelo. Now Angelo and his son Mike run the business Mike's great-grandfather started.

Sitting shoulder to shoulder at the counter, Angelo and Mike scoff at "egg noodles" and extoll the pedigree of their long-cooked "gravy" sauces: the "restaurant sauce," which is dark and meaty enough to be mistaken for chili at first glance, and the lighter "store sauce" dotted with ground meat. Both are earthy and salty with a hint of nutmeg, and for loyal customers, they represent old-school, homestyle Italian cooking. "People move out of the area and we ship to them," says Angelo's wife, Roberta Marcelli. "A lot of our customers have," she lowers her voice, "passed away. A lot of them are older." But she's quick to add that younger folks are drawn in by the newer dishes and the family atmosphere, evidenced by the basket of children's toys in the corner.

But the ravioli and gravies are the cuisine of another era and reviews, online and word of mouth, ricochet between devotion and scorn (though the service is universally praised). And what is a homey and familiar dining room to some is simply run-down to others. None of this seems to affect their loyal following, for whom news of the restaurant's closure was met on Facebook with despair worthy of a tragic Greek chorus.

It's not a lack of customers that led the family to decide back in May to shut down, says Mike Marcelli. "If we could find help to cook, we'd still be doing it," he says.

While they've had additional cooks for years at a time, the Marcellis have mostly been in the kitchen themselves. After a stint as a deli from 1953 to 1973, the space was converted into a restaurant with a few tables and Angelo did the cooking in the roughly 8-by-10-foot kitchen that once served as an office. Roberta, who worked for 34 years for California Children's Services, would come in after work and cook for the evening shift. Sometimes she'd cover a lunch so Angelo could take a break. After a brief retirement, she was back in the tiny, chaotic space, working, as she is today, with six pots over four burners on one side and keeping an eye on the blackened stove on the other side, where one tall pot bubbles with sauce and a mountain of meatballs rises from another.

"She's been the driving force behind the restaurant and the catering, too," says Mike, adding that she created the bulk of the menu like the pesto and alfredo pastas. But after 44 years in the kitchen, Roberta, who's cooking today with a leg brace after surgery for a torn ligament, is ready for retirement.

Finding reliable help has become more difficult lately, says Angelo. "Nobody wants to work," he says, swiping his hand over his white push-broom mustache. He says the restaurant went through three cooks in a matter of months. "One went on a 10-minute break and I haven't seen him since."

Mike says it was either close now or in another four years at the most anyway, and his parents would like to travel and enjoy life. What will happen to the building, which the Marcellis own along with the one next door that houses a gun range (they say you can only hear shots once in a while), is something they're not commenting on just yet. Asked if they'd sell the business if a sweet enough offer came in, Mike is cagey, only saying they have a number in mind. But Angelo says yes. "If the price is right," he says, "we'd be gone after dinner."

Jennifer Fumiko Cahill is the arts and features editor at the Journal and prefers she/her. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 320, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @JFumikoCahill.

Speaking of...

-

Return of The Valley of the Giants

Nov 2, 2023 -

Humboldt History, Maui Fires and Fair Baking

Aug 25, 2023 -

Salmon Runners, Kinetic Racers and Anti-Chinese History

Jun 3, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

Hole Food

- Apr 27, 2024

-

SCOTUS on the Homeless, CPH Protest and Local Entertainment

- Apr 26, 2024

-

Look Up for Rooftop Sushi

- Apr 19, 2024

- More »