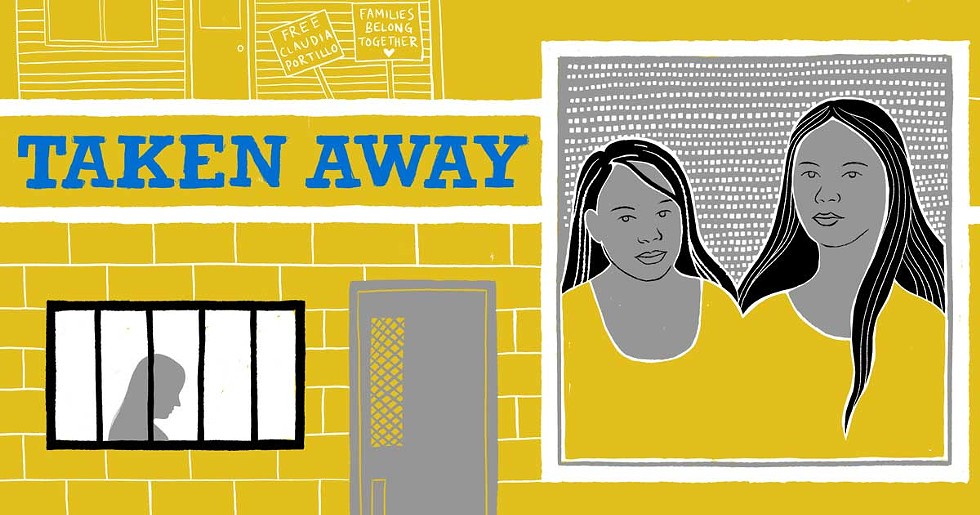

Taken Away: How an Arcata mom is working to rebuild what was lost during an immigration detention

By Kimberly Wear [email protected] @kimberly_wear[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Claudia Portillo is back in her Arcata home but it doesn't feel like the same one she left behind. And what seems like it should be a happy ending is instead just the beginning for the young mother and her four daughters, who are working their way back to a semblance of how things used to be while facing an uncertain future.

Once broken, some things prove hard to put back together.

After being unexpectedly detained for seven months in an immigration facility hundreds of miles away, Portillo says she has struggled to regain her footing in the weeks following her release. Some days she feels like a stranger to her own children. Sometimes she feels like a stranger to herself.

Portillo says things were different before that day in November when she headed down to the Bay Area for a regular check-in with immigration officials and was taken into custody. She had a tight bond with her girls, a home of her own and a business to run.

"I was living a perfect life," she says. "My girls were living a perfect life and we were doing so good. I mean, I'm not going to tell you it was perfect-perfect but we really were doing good. And then this happened and I can't just sit here and blame anyone else but the system."

During the time Portillo was away, unsure whether she would be deported to a country she has not seen since she was 7, the family's fabric began to fray. Where parenting once came easily, there is now hesitation. And after essentially being on their own for all those months, her two teenagers stiffen as she reasserts her role in their lives. They are, Portillo says, getting to know each other again.

"This is not what I left," she says.

The detention also forced Portillo to lay bare secrets she had been protecting her children from, including her immigration status and traumatic events in her past. But she also makes clear how grateful she is to be home and for the community support that helped bring her back.

"All of this help," Portillo says, "it's been amazing. I appreciate everything the community has done for me."

During Portillo's detention, much of the burden fell on the shoulders of her eldest daughter, Avigail, who was 17 when Portillo was taken into custody. She was left to pay bills, watch over the house and put food on the table for herself and her 14-year-old sister, while Portillo's two youngest girls stayed with other relatives.

Avigail kept going to school — at least for the most part — trying to outwardly pretend that nothing was wrong. And, for a short time, few beyond her immediate family circle knew what was happening. That's how Avigail wanted it.

"I don't like to ask for help," says the recent Arcata High School graduate who is headed to Chico State University in the fall and hopes to become a social worker. But, she acknowledges, "It was stressful."

When a local news outlet reported about her family's situation, it opened up extra lines of support for the girls — with teachers and others reaching out to help — but it also left Avigail and her younger siblings vulnerable to classmates' taunts and well-meaning but tone-deaf attempts by some adults to get them to talk about what was happening.

That included a teacher who Avigail says asked her to explain how her mother's detention worked in front of her classmates. She responded by saying that she didn't feel like talking about it. "I'm not a show," Avigail says.

Portillo says her other daughters had similar experiences, including her first grader, who was just 6 at the time and didn't know what was happening, having been told her mom was away at school. The sisters also endured hateful comments from kids who said Portillo was going to be deported or that they should be, too. "They had to go through a lot," Portillo says, wiping away tears.

Avigail says that with her mom gone, the house felt empty. They were struggling and went for long periods just eating tortillas and eggs. At one point, Avigail thought about selling some furniture to help make ends meet. Soon the cable and wi-fi were shut off.

Untethered from their mother's watchful eyes for the first time, Avigail and her sister also began to stray from the straight-and-narrow path she had set down. While family members did check in on them, the teenagers were largely on their own.

With seemingly little to do but sit around and stare at the walls, Avigail says she and her sister started going out to parties — sometimes with drinking and smoking — and staying out late.

"It was fun to be out with friends at 2:30 in the morning, even if all we were just doing was taking a walk on the beach," Avigail says.

Before her detention, Portillo says she was always the kind of mom who would check to make sure a parent was going to be at a party before letting one of her daughters attend, even sometimes dropping by to see what was going on for herself.

And although Avigail says she wouldn't describe her mother as overly strict, she quickly notes, "I wouldn't want to get my mom mad."

Avigail admits that it's hard to have so many rules again, to not be able to go where she wants, when she wants or to have friends come over without asking permission.

"We were best friends before she left," Avigail says of her mother, "but we've all changed."

Portillo says it's painful to hear about what her girls were doing while she was in detention. "That's just not the way I raised my kids," she says. But, at the same time, she doesn't feel like she's in a position to judge them.

"That," Portillo says, "is just not what they need right now."

Avigail eventually entered an independent study program, finishing up the last of her classes well before the end of the school year. She initially didn't want to walk on graduation day but Portillo insisted.

While she couldn't be there in person to see Avigail receive her diploma, Portillo was able to watch some of the ceremony via video chat from Avigail's cell phone. But just when the time came for Avigail to cross the stage beaming in a cap and gown borrowed from the school, the connection was lost.

It was one of many important milestones Portillo missed as a result of her detention. There were all of her daughters' birthdays, Thanksgiving, Christmas and the fifth and eighth grade graduations of her two middle daughters, a long-anticipated day that was supposed to see all of them wearing matching outfits.

"That's not at all what I had pictured all those years," Portillo says. "It was devastating not to be there."

The transition back to family life has been a hard one and Avigail says her mom is not the same person who left in November. She doesn't stand up for herself the way she once did. She just seems different.

"We feel like her being in the detention center made her soft but it made us harder," Avigail says.

Her mother agrees: "It changed me. That place changed me ... I do consider myself a strong person but in the detention center I was not strong. I would consider that the lowest of my lows."

Portillo suffered a mental breakdown during her detention, unable to get out of bed or communicate with anyone for two full weeks. She has sought help and is now working to rebuild her family.

She says she feels guilty that Avigail was thrown into so many adult roles while just 17.

"I'm sure there would have been more help for Avigail if she would have reached out to people," Portillo says. "There were times that she didn't have anything to eat. But she wouldn't reach out. I know that's just who she is but it breaks my heart."

There was a time when the 33-year-old Portillo would have been an unlikely target for a detention, let alone a deportation order. Brought to the United States as a young girl, the El Salvador native is the mother of four American-born children and has deep connections in her community, evidenced by the fact that its members turned out in force to lobby for her release and quickly raised the $12,000 bond set by an immigration judge last month.

But things have changed since Donald Trump was elected president and began rolling back many of the protections that President Barack Obama's administration afforded undocumented immigrants.

Within 100 days of Trump signing an executive order clamping down on undocumented immigrants last year, the number of "enforcement and removal operations" conducted by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement increased by nearly 40 percent, according to the agency. And a San Francisco Chronicle review of ICE stats found detentions of noncriminal immigrants rose by a similar amount between January and August of 2017, compared to the previous year.

Richard Boswell, a professor at University of California Hastings College of the Law who specializes in immigration law, says there's been a noticeable shift in how immigration proceedings are handled under the Trump administration.

In the past, high-profile cases involving individuals accused of criminal conduct or posing some other public safety concern would be prioritized for detainment and deportation proceedings.

"But that's not happening anymore," says Boswell. "It's everyone they catch or that they know of and they are putting them in the proceedings and that overloads the courts."

The only ones benefiting, he says, are the companies running the private detention centers.

From his perspective, it's simply a political ploy meant to satisfy a certain segment of Trump's base, one that Boswell says doesn't make any sense but comes at a great personal cost to the families involved. Many of the individuals who are now ending up in the immigration court system would likely be able to obtain some sort of status at some point, he says.

"It's almost like they are trying to criminalize everybody and the ultimate goal is to scare as many people as possible so that some people say, 'I don't want to be here' or 'I can't afford all this stuff, I'm going home,'" Boswell says. "That's the purpose. That's the underlying purpose."

The result, he says, is an overwhelmed system that is unable to process the onslaught of cases. And even more are slated to come online after Trump announced recently that he is ending the temporary protective status for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from half a dozen countries — including El Salvador.

In Portillo's case, she was detained in November of 2017, about nine months after Trump signed his executive order, despite having made regular check-ins with ICE for the last six years after she received a citation for driving on a suspended license, an offense that was itself related to her immigration status.

Such traffic infractions are how some immigrants living otherwise quiet lives in communities across the nation now find themselves thrust into detention and deportation hearings.

It's something the Department of Homeland Security even noted in a frequently asked questions handout from March of 2017, released to address how the agency would "implement the guidance provided by the president's order" on immigration enforcement.

In outlining whether ICE would move to deport people stopped for driving without a license, often an immigration-related issue, the answer was blunt: "All of those in violation of immigration law may be subject to immigration arrest, detention and, if found removable by final order, removal from the United States."

But after a cursory examination of Portillo's situation, Boswell believes she actually has quite a few options, including requesting what's known as a "cancellation of removal" to provide relief from deportation.

Since Portillo is the mother of young, U.S.-born children and has been in the country for more than 10 years, the law professor says he believes she can successfully argue that her children would face great hardship if they had to go with her to El Salvador — a place they don't know and one that presents a very real threat from rampant violence.

"There is a reasonable case for her to make that showing," Boswell says, noting the process will likely take years.

And when Avigail turns 21, as a U.S. citizen, she can petition to have her mother become a permanent resident — something Melania Trump is widely speculated to have done for her parents. Both options present potential paths to citizenship, although neither is guaranteed, Boswell notes.

Portillo — one of an estimated 1.17 million immigrants from El Salvador who fled poverty and dangerous conditions to come to the United States — has only vague memories of her childhood there. She says she suffered abuse and moved frequently after her mother left for the United States when Portillo was just 9 months old.

Portillo arrived in the United States at the age of 7 after human smugglers – often called "coyotes" — were paid some $30,000 to ferry her, her sister and a nephew into the country to be reunited with family.

But life here came with its own adversity. Portillo says she was violently assaulted by a friend's brother and his friends when she was 11 — another chapter of her life that she had tried to shield from her daughters. As the victim of a violent crime, Portillo could apply for what's known as a U Visa. To do so, she had to obtain the police report from all those years ago. It was sent to Portillo's house, where Avigail, who took on the duty of tracking down documents her mother needed for her immigration proceedings, retrieved it.

"Now, they know everything," Portillo says.

Asked about the difficulty of that moment, when she learned of her mother's assault, Avigail replies simply, "My mother didn't raise me to be weak."

Portillo describes having Avigail when she was 14 as life-changing. It helped her see that her life had value and gave her a strength she didn't realize she had. "The moment I saw her, I fell in love," she says.

While Portillo had protective status for a time, she eventually found herself having to make a choice between paying hundreds of dollars in fees to re-register each year and maintain a work permit or paying her rent and feeding her children.

Boswell says that one of the questions he often hears is why people like Portillo don't simply clear up their status. He says people just don't understand the complexity of the legal process involved.

There are many places people can make a mistake and set their case back, he says, especially if they don't have an experienced attorney. But legal services are expensive and come on top of an application process that costs thousands of dollars on its own.

For some, the process simply becomes too overwhelming and cost prohibitive.

Boswell asks people to imagine what would happen if everyone in the United States was required to pay a $500 fee to file their mandatory tax returns, regardless of whether they could afford it or if they were expecting a refund.

"A lot of people would not be filing" because they simply would not be able to pay the fee, Boswell says. Then, he says, imagine that you get in trouble for not filing and you end up with "something right out of Kafka."

Looking back, Portillo says she would have tried to do things differently regarding her status, but she was too naïve and scared. And, Portillo insists on addressing a question some have raised about why she didn't simply marry her longtime partner to resolve her immigration issues. (They are no longer together, Portillo notes.)

"That's just wrong to marry someone for a paper," she says adamantly. "That is not what I want to do."

Portilllo and her daughters are not public people by nature and it's been difficult adjusting to life in a small community that is now intensely interested — and, in some cases, invested — in their situation.

While emphasizing how much she appreciates all the support and the incredible way people donated to help raise her $12,000 bond, Portillo says there is also a flip side.

Sometimes her younger girls become confused by all the attention Portillo receives, noting that people will approach her crying even though they don't personally know her. And Avigail has bristled at what seems to her like a sense of entitlement about her family's situation, with people interjecting themselves — and their opinions — into their personal lives, often leaving them feeling exposed and a bit judged.

Portillo says she doesn't mind and hopes that being honest about her story will help other local immigrants and give the larger community a better understanding of the obstacles people in her situations face.

For now, they are trying to pick up the pieces of their lives and move forward but the trauma her family has suffered is severe, Portillo says. She feels like all the dreams she had to build a brighter future for her girls have been shattered, waded up like trash by the government and thrown away. Avigail's college fund and the nest egg Portillo painstakenly saved over the years through hardwork cleaning houses are gone, wiped clean to pay her legal expenses and the bills that came due during her detention. Now, she says, they are left to take things one day at a time.

"It's just tough," Portillo says. "I don't know how it's all going to work out but only pray that it's going to be OK."

Kimberly Wear is the assistant editor at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Speaking of...

more from the author

-

Huffman Joins Colleagues in Calling for Biden to ‘Pass the Torch’

- Jul 19, 2024

-

SECOND UPDATE: Victim of Fatal Shooting Identified

- Jul 17, 2024

-

Eureka Man Killed in SoHum Crash

- Jul 1, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023