'I'm the Monster'

After 21 years in prison, a Eureka murderer is recommended for parole

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Francine Schulman has forgiven the man who murdered her 14-year-old daughter and left her alone and bleeding on the South Jetty. In fact, it's taken nearly 25 years but Schulman says she now feels it is time for Thomas Jerome Dunaway to be released from state prison, where he's been held since June of 1997.

Schulman may soon get her wish as a parole board recommended last month that Dunaway be released from Mule Creek State Prison to become a free man for the first time in his adult life.

"When I went to the parole hearing, I felt it was time. It was time to forgive him," Schulman says. "I would rather the government release him. I want to get my life back. (Holding Dunaway in prison) will never bring back Amber. It will never change the trauma or prevent the changes that have thrown my family into the abyss. I just want to keep going forward."

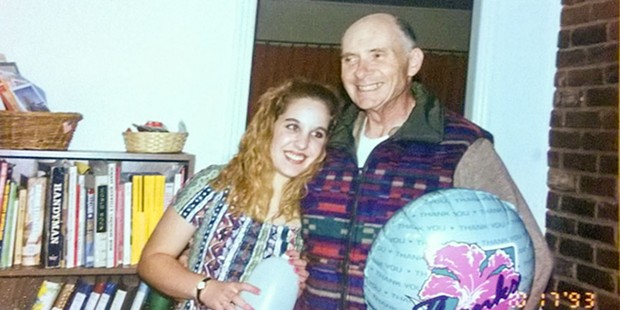

Asked about Amber Slaughter, the eldest of her three daughters, Schulman smiles broadly.

"She was like a fluttering butterfly," she says, adding that Amber was the only of her daughters to get her curly, red hair. "She was like a mini-me."

Amber loved animals and raised pigs, ducks, geese, sheep and rabbits in 4-H. She often helped Schulman with her landscaping business and was good to her younger sisters, who were three and five years her junior. She was also bullied in school, which had a profound effect on her, Schulman says.

Around midnight on Jan. 23, 1994, Amber snuck out of her house and got into a car with three friends — Dunaway, who was 17 at the time, Thomas Winger and Abraham Gerving, then both 16. On several occasions, Amber had come over to Gerving's house, where she'd hang out with the three boys, who'd take turns having consensual sex with her, according to court testimony. The boys found out that Amber had told some people at school about their encounters and Winger was afraid word would get back to his girlfriend. So that night in January, the three teenagers — all of whom were founding members of the Eurekaville Crips gang, with Dunaway having developed a reputation as the enforcer — decided to murder Amber. They picked her up from her parents' house and drove her down to the jetty where, on Dunaway's signal, Winger shot Amber in the back of the head without warning. (After reaching a plea deal with prosecutors and testifying against Winger and Dunaway, Gerving was paroled about halfway through a 16-year prison sentence. Winger died in prison.)

At Dunaway's parole hearing on Nov. 28, retired Assistant District Attorney Wes Keat called the killing "brutal," "senseless," atrocious" and "planned." But the parole board's task that day wasn't to re-litigate the murder. It was to determine whether Dunaway — who was sentenced to serve 25 years to life in prison for a crime he committed while still a juvenile — still poses a danger to society. A year earlier, a different parole board had decided that he didn't — that, despite Schulman's pleas at the time to keep Dunaway in prison for the rest of his life, he had been rehabilitated — but Gov. Jerry Brown took the rare step of reversing its decision. Dunaway had remained violent in prison, Brown said, and didn't express sufficient remorse or insight into his actions.

On Nov. 28, answering questions from Presiding Parole Board Commissioner Michele Minor, Dunaway walked the parole board through his first 17 years of life, trying to explain what brought him to that moment he and his friends killed Amber and how he's worked in recent years to deconstruct his young psyche and gain control of his emotions.

Dunaway said he he grew up in an abusive household. His father was a gang member who was in and out of prison. His stepdad beat his mother and his grandfather beat his stepdad. He told the board when he was a young kid, his grandfather would take him and his sister to the park, where he'd make Dunaway fight random children.

"He would point some kids out sometimes or he'd go go out there and tell me to go get into a fight, 'Let me see what you got,'" Dunaway said. "And, uh, if I tried not to, he would beat me up in the car until I got out and went and fought ... if I won, then it was like we were friends and he was proud of me and he would reward me with like ice cream or McDonald's afterwards, and, uh, if I didn't do good, he would smack me around a little bit and belittle me and talk down to me."

Dunaway said he later learned that while he was out of the car fighting, his grandfather would molest his sister, for which he was later arrested and jailed. Dunaway said was also molested by a neighbor when he was 9.

The family moved to Eureka when Dunaway was 14 and he told the parole board he was "angry," "insecure," "self-conscious," "impulsive" and "selfish." He said he craved respect and validation, and found both through committing acts of violence.

"I didn't have an identity that was based on anything other than being violent and being of worth to my friends that were also violent," Dunaway said, adding that the gang he formed filled emotional gaps in his life. "As dysfunctional and as ignorant as that sounds, we just — we formed something to where we felt we belonged, and we felt like we were a part of something, and we weren't alone in the world no more."

Even after entering prison, Dunaway said his mindset was unchanged. He fought regularly, trafficked in contraband and associated with gang members. It wasn't until 2009, when a fellow inmate he admired said they couldn't be friends anymore because of Dunaway's violent tendencies, that he set about bettering himself. Over the last nine years, he's participated in a variety of self-help programming, including substance abuse treatment, counseling and classes in victim awareness and anger management. He said he's come to realize he's spent much of his life seeking external validation with no regard for how his actions have impacted others. At one point, Minor asked him about Amber, about how the night of Jan. 23, 1994, must have felt from her perspective.

"I think about her being scared and feeling betrayed. ... We were supposed be her friends," Dunaway said, sobbing. "She needed acceptance. She needed friendship. She needed validation. She needed to be a part of something. She needed all — basically, the same things that we needed, I believe ... and we took advantage of that."

Toward the end of the hearing, Minor tried to get to the heart of the board's decision. How can the board and the governor be sure Dunaway has taken responsibility for his actions, that he understands them and he would leave prison markedly different than when he was admitted 21 years ago?

"I didn't know how to change who I was," he said. "I thought I was stuck being that person. I thought that that's all I was destined to ever be was this scumbag white trash from a scumbag poor white trash family, and that was my identity, and since then I've developed an identity. I understand who I am. I understand that — that things I do such as ... being a 12-step counselor and mentor to other inmates, these things allow me to gain the self-worth I lacked all my life. They allow me a true sense of accomplishment and they make me feel good about myself and it shapes a good, positive, healthy identity that I never had as a kid, that I didn't have until I was 30-something years old. And I look back and I'm ashamed that it took me that long to develop it. I'm ashamed that it took me all those years to really understand how I impacted the Slaughter family, what I did to Amber, what I did to her sisters, her mother and her father, her grandparents, her cousins, what I did to their community, and I'm aware of what I did because I hear the words they say and their voice. I hear the words they say to describe what I did to them. I listen. I understand. I'm the monster."

Schulman says she believes Dunaway, that she feels the change in him. Working toward her masters in social work at Humboldt State University, Schulman is forming Broken Spirits Rising, a grief support group for those who have suffered the murder of a loved one, and is working as a specialist advocate intern with Victim Witness.

"What does it mean to forgive someone who has murdered your loved one?" she asks. "It has taken me a quarter of a century of process to get where I am."

On Nov. 28, after deliberating for about 20 minutes, the parole board recommended that Dunaway be released from prison. The decision will become final in February if not reversed by the governor.

Thadeus Greenson is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Speaking of...

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

more from the author

-

Deputy Shoots Cutten Shooting Suspect

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Officials Weigh in on SCOTUS Case's Local Implications

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Arcata Lowers Earth Flag as Initiative Proponents Promise Appeal

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023