[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Artist and blacksmith Monica Coyne works in steel and her sculptures are riddled with reminders of the forge. That's enough to make them strange. We're used to thinking of steel as a substance that comes in identical prefab units, from I-beams and girders at construction sites to the machine-finished tools hanging on the wall at the hardware store. We're not accustomed to making the connection from human hand to forged implement.

But Coyne's sculptures treat these obdurate materials in a way you very possibly haven't seen before. This body of work showcases steel pleated like an accordion, folded like linens and crimped like the hairstyles of the 1980s. This estranges but also humanizes the material, making it relatable. A sculpture like "Contrapposto," in which you see the transition of unarticulated steel to sinewy likeness, reminds that steel does in fact belong to nature; it does not emanate direct from the abstract object-world that 20th century visionaries proposed as nature's replacement.

It's 2020 and even those who never sought out the poetry of William Butler Yeats are waylaid by regular reminders in the news that the center cannot hold. This comment is often put forward as a metaphor for the state of society but in the case of Coyne's compositions, it's a statement of fact. Female bodies figure in most of the sculptures, seldom at rest; their facial expressions are checked out, bodies wholly engrossed in some athletic ordeal of transformation or transit.

Tightly wound athletes modeled in motion stride or surge forward, muscles engaged, their poses often the opposite of balletic. Feet flex; arms flail to the sides, as if seeking balance. Centrifugal forces often send these figures flying out from a vacated center, the way swings suspended from a carnival ride will orbit a spinning core. Even functional pieces, like the glass-topped "Dovetail Table," are constructed in ways that makes it possible for them to uncouple. Their stability is not an immutable characteristic but the outcome of force applied in a vector direction.

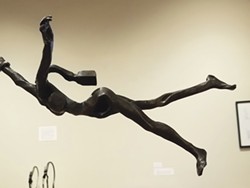

The sculpture "Nude Midstride" appears to be suspended in a process of becoming. Its form consists of a scissor-like pair of pinchers with a big rivet at breast level and a midsection that segues incongruously into a sensuously curving haunch. This figure lacks a head but she's got a multitasking industrial fragment subbing in as an outstretched arm. The sculpted steel slides easily into and out of representation, flickering like a mirage on summertime blacktop — only in space, instead of time. In the sculpture titled "Flying," three related figures spring from a swooping base. Who ordains this collective metamorphosis? Is it of the figures' volition? The piece brings the word "rapture" to mind, in the sense of abandon but also in the born-again sense of a group levitation or lift-off.

Redirected forces and repurposed materials also characterize Coyne's off-the-grid studio practice in Southern Humboldt, where her forge is powered by solar panels and a hydroelectric Pelton wheel. Acute awareness of blacksmithing as an energy-intensive activity and a commensurate interest in energy conservation has led her to arrive at some ingenious methods of forge management. "About nine years ago, I began researching if I could somehow make my own oxygen," she wrote in an email. "This would greatly lower my fuel consumption. I found out that I could!"

It's a lesson in chemistry. "I use an oxygen/propane torch and a propane forge," Coyne continued. "The steel needs to be heated to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit. The flame temperature of propane in air is 3,596 F. The flame temperature of propane in oxygen is 5,108 Farenheit. So propane mixed with oxygen burns way hotter, which saves heating time and propane. Oxygen is clean and not a fossil fuel. I bought an oxygen generator. It splits the nitrogen out of the air and slowly fills a bottle with oxygen. The power that I use to do this is renewable, solar or hydro. So my solar panels fill my oxygen bottles and my oxygen cuts my fuel use by almost a third."

When Coyne studied industrial arts at Humboldt State University, her emphasis was woodworking and furniture. Later, when she trained as a blacksmith, her woodworker's appreciation for joinery translated into the forge. Her works implement a range of joins, from the familiar dovetail to more complex fastening systems rooted in practices of traditional Japanese cabinetry.

"Joinery is a puzzle," Coyne mused. "Using joinery, I can create pieces that can be kinetic, or that can be taken apart .... I look at a cut woodworking joint and develop a method for making that joint by moving the material. This involves projecting where the material will go and what it will look like after it is moved. For instance, with a hole. In wood I would drill the hole and remove the material. When I forge a hole in metal, I punch a slit and then force a drift (a long, tapered tool) through the small hole and push the sides of the metal out around the hole until I get the size hole that I want."

Steel might be gendered male in the popular imagination but these pieces' insistent evocation of the forge's heat and light propose a re-gendering. "Woman-axle," for instance, is part ecorche figurine, part crankshaft, caught in a moment where neither term will suffice. Plenty of male artists who have sculpted in steel have referenced its strength in stasis. In contrast, "Woman-axle" and many of the other sculptures in this exhibition celebrate steel as a dynamic force that draws power from its shape-shifting capacity for change. The nature spirits like dryads and djinn evoked in their titles reinforces this association. Coyne's pieces won't let you forget the slipperiness and fluidity that steel displays when subjected to extreme heat and pressure: It's literal grace under fire.

Monica Coyne - Iron Dryads and Other Forgings will be on view at the Morris Graves Museum of Art from Sept. 16 through Nov. 8.

Gabrielle Gopinath (she/her) is an art writer, critic and curator based in Arcata. Follow her on Instagram at @gabriellegopinath.

Speaking of...

-

Music Today: Sunday, Feb. 18

Feb 18, 2024 -

Full Circle Journey

Oct 26, 2023 -

Truth Units

Sep 7, 2023 - More »

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »