The Soeth Files

Local officer's record includes two shootings, $1.1 million in settlements, mistruths and little accountability

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson

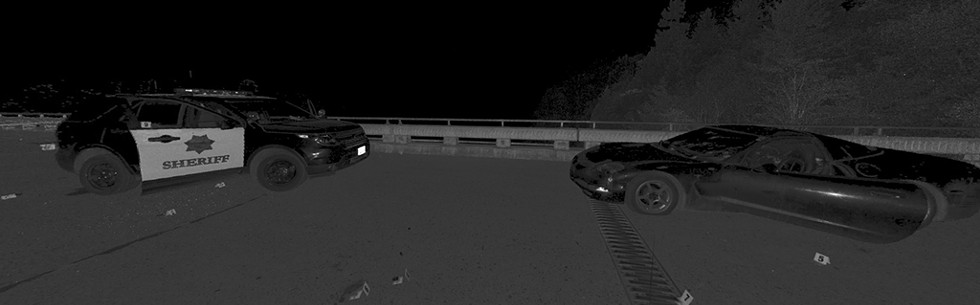

The scene of a July 14, 2017, shooting on Martin's Ferry Bridge, in which Humboldt County Sheriff's Office deputies opened fire on a night watchman in a parked car.

[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The moment the dog bit, five officers were on top of the prone suspect. Two knelt atop their legs, another held their handcuffed left arm, one knelt on the middle of their back and the other held their right wrist, struggling to pull the arm back into cuffing position. Then Humboldt County Sheriff's deputy Maxwell Soeth ordered the dog, a tactically trained Belgian Malinois named Yahtzee, to bite. The dog's teeth clamped down on the suspect's arm for more than 20 seconds, not letting go until Soeth grabbed Yahtzee by the throat, compressing the dog's airway in what's known as a "choke off" maneuver.

What exactly transpired in these moments in the northbound lane of U.S. Highway 101 near Shively Road before dawn that drizzly Saturday morning three years ago would become the subject of controversy within the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office. An internal affairs investigation and ensuing disciplinary process would span more than a year and leave Sheriff William Honsal deeply split from his command staff in their views of Soeth's conduct and whether the deputy should face discipline.

The case would also lead to a snowballing North Coast Journal investigation starting with a single tip and leading to a lawsuit seeking release of police dashcam videos and scores of records requests for other documents — more than 2,000 pages of internal affairs reports and court filings related to four incidents involving Soeth. These documented acts of violence left two people shot, one bit, Soeth's own son bruised and local governments paying a combined $1.1 million to settle lawsuits.

This is a story about a single problem officer with a decade-long track record of questionable decisions and uses of force who, at least temporarily, appeared to have lost the trust of his agency but wasn't fired, and now is back on patrol. But it's also a story about the apparent reticence of law enforcement agencies to turn a hard investigative eye toward their own following critical incidents.

Numerous attempts to reach Soeth by email, phone and text message for this story were unsuccessful.

Amid the backdrop of a national reckoning over policing and the use of force, and California implementing perhaps the most strident police accountability law in its history, the events involving Soeth also raise significant questions about law enforcement's ability to police its own — and prosecutors' ability to hold officers to account. Together, the incidents and their aftermath paint a pattern of escalation and dishonesty that's come into public view as police departments throughout Humboldt County and across the country have espoused renewed commitments to de-escalation, accountability and integrity.

The ramifications of the Soeth files coming into public view are potentially complex, but the incident that started the process was not, at least in the eyes of Ernie Burwell, a former K-9 handler for the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department who now works nationally as an expert witness.

Asked to review dashcam footage from two California Highway Patrol cars that captured Yahtzee's bite on April 4, 2020, Burwell doesn't hesitate.

"I policed for 30 years and I know a crime when I see one," he told the Journal, saying he believes the video shows Soeth committing assault under the color of authority. "The suspect was no longer fleeing at the time force was used. [They] never threatened any officer, did not assault any officer. The handler was trying to get the dog to bite and [the driver] was being used as a bite dummy."

Almost a decade before Yahtzee bit that driver on the side of U.S. Highway 101, Soeth, then a Fortuna police officer, shot and killed a 26-year-old man on O Street shortly before dawn on a wet Friday in 2012. Talking to the Journal a few days later, then Police Chief Bill Dobberstein said Soeth had opened fire as Jacob Newmaker raised a collapsible metal baton to swing at another officer, adding that he expected Soeth to be back on duty soon and the department's investigation into the shooting to be "wrapped up by the end of this week."

About six months later, the Humboldt County District Attorney's Office cleared Soeth of any criminal wrongdoing in the case. A letter detailing the office's review of the shooting states Newmaker was resistant and aggressive, and that he had a "potentially toxic" level of methamphetamine in his system as he ripped the baton from Soeth's hand and swung it at Sgt. Charles Ellebrecht's head, prompting Soeth to open fire.

But what the letter does not say is that the version of events Soeth relayed to investigators during the investigation both changed over time and was "materially contradicted" by physical evidence in the case, as an appellate court would rule in 2016. Instead, the review simply relied on Soeth's word for what happened.

The documents tell a different story. On March 15, 2012, with Soeth working patrol, Newmaker showed up at the Fortuna police station, shoeless and disheveled, asking to talk to a sergeant at 11:45 p.m. Someone, he said, had been chasing him.

When Soeth came to speak with him, he asked Newmaker if he wanted to make a report. Newmaker said no, he just wanted a safe place to be.

"I advised him that this isn't really a shelter ... unless you need to make a report, you need to leave," Soeth would later tell investigators.

Newmaker then asked for a ride home, or at least for an officer to follow him to make sure he got there safe. Soeth said he wasn't "a taxi service" and walked Newmaker to the door. A couple hours later, their paths crossed again when Soeth, out on patrol, spotted Newmaker parting ways with a friend he'd been talking to on Second Avenue. The officer decided to follow him to make sure he didn't "smash and grab any cars" or "try any door handles." At Ivey Lane, Newmaker, still shoeless, stopped and again asked the officer for a ride.

"I said, 'No, I'm just keeping an eye on you so you don't, you know, break any windows and steal anything,'" Soeth told investigators, adding that he followed Newmaker another mile to his mother's house.

Soeth was wrapping up his shift later that morning, around 6 a.m., when a call came in from a woman in the upscale neighborhood of Angel Heights Drive, who reported someone banging on her front door and window. Soeth and Ellebrecht were dispatched to the scene, where they learned the man was last seen heading east on a bicycle. Soeth began checking the area in his patrol car, using his spotlights. At the corner of 11th and P streets, Soeth saw Newmaker stopped on a bicycle. Soeth turned on his red and blue emergency lights to initiate a traffic stop — lawyers representing Newmaker's family would later argue this constituted an illegal stop, as he didn't have probable cause, or reasonable suspicion that Newmaker had committed a crime.

But when Newmaker saw Soeth's patrol lights go on, he fled, pedaling fast down 11th Street, dropping two steak knives as he went, with Soeth now in pursuit. This continued for several blocks at varying speeds, after which Soeth activated his car's siren, too. Newmaker eventually ditched the bicycle, at which point Soeth parked and caught up to him on foot, ordering Newmaker to "get on the ground."

According to Soeth — there are no witnesses to the encounter, it was not captured on video and Soeth did not activate a device that would have made an audio recording — Newmaker didn't comply, but instead laid "down on the hood of [a] car with his arms bent and his hands down in front of him." Soeth told investigators he again ordered Newmaker to the ground but he didn't move, at which point Soeth said he grabbed him and threw him to the ground, setting off a cascading escalation of force and a series of tactical errors as the officer struggled to gain compliance.

According to Soeth's account, Newmaker was actively resisting on the ground, so the officer decided to stun him with his Taser. But as Soeth did so, he later told investigators, Newmaker grabbed the Taser with his right hand and then Soeth said he felt something "wrap around" his leg, and figured it must be Newmaker's left arm.

"I pushed off and run — step back so that I don't get taken down to the ground," Soeth said, saying he also dropped the flashlight he was holding under his left armpit at the time.

Amid the commotion, Newmaker got up and ran away, according to Soeth, who said he then reported over the radio that he was involved in a foot pursuit, having failed to previously notify dispatch he was leaving his car or contacting a suspect, as would be standard protocol.

Police procedure experts interviewed by the Journal questioned Soeth's tactical decisions, including repeatedly engaging in foot pursuits with an identified suspect with a known address in town wanted, at most, on suspicion of committing a misdemeanor. Nonetheless, Soeth gave chase for a couple of blocks until Newmaker stopped running on the sidewalk in front of a parked car on O Street.

"He rips his pants off, is flexing, takes an aggressive fighting stance," Soeth told investigators of the encounter, which, again, was not recorded.

Soeth said Newmaker was yelling something but he couldn't recall what, and that he did not respond to repeated orders to get on the ground. Soeth then shot Newmaker with his Taser, its probes lodging in his chest, with the ensuing shock sending him to the ground. When the Taser finished cycling the first time, Soeth said he ordered Newmaker to put his hands behind his back but he didn't, so Soeth said he cycled the Taser again, sending another jolt of electricity through Newmaker's system.

At this point, Ellebrecht arrived on scene, responding to Soeth's call of a foot pursuit, and pulled his patrol car up along the sidewalk, bringing Soeth and Newmaker into the frame on Ellebrecht's patrol car dash camera, which was recording. When the two come into view, Newmaker is on his back on the sidewalk, naked from the waist down with a white T-shirt on. Soeth is standing over him, a Taser in his left hand and a collapsible baton in his right.

As Ellebrecht gets out to help, Newmaker pulls the Taser probe wires to his mouth and bites through them, then tries to get to his feet, prompting Soeth to hit him across the back with his baton. Soeth delivers at least two more blows with the baton as Ellebrecht tries to secure Newmaker's hands. Soeth is seen in the video fumbling with the baton for a moment before dropping it on the sidewalk to put hands on Newmaker, who is now wedged between the curb and a parked car. Throughout the interaction, Ellebrecht would later tell investigators, Newmaker, with whom he went to high school, kept repeating, "You know me," while resisting the officers' efforts to cuff him. The two officers can be seen in the video struggling at an awkward angle to secure Newmaker's hands before they decide to pull him into the street behind the parked car, where there's more room to maneuver. The move also places the parked car between the struggle and the camera in Ellebrecht's patrol car, blocking out much of what happened next from the its view.

After a few seconds, the video shows Soeth walk back to the sidewalk to retrieve the baton before returning to Newmaker and Ellebrecht, who are still struggling on the ground behind the car. The three are then hidden from view for about five seconds, after which Ellebrecht and Soeth stand up. What happens next passes quickly and is difficult to decipher, but you can see the officers appear to step back as Newmaker seems to lunge, lose his balance and fall to the ground. As this happens, Soeth can be seen pulling his firearm before he approaches Newmaker, now on the ground, in what law enforcement describe as a "fire-ready" position.

Soeth would later tell investigators he attempted an arm-bar maneuver with his baton to pry Newmaker's arm into cuffing position but that Newmaker wrested the weapon, slippery from the rain, from him. When initially asked to describe what happened by then Humboldt County District Attorney Chief Investigator Mike Hislop after the shooting, Soeth was clear and concise, according to a transcript of the interview:

"He jerks the batons [sic] out of my hand. I yell, 'He's got my baton.' I create some distance between me and him, draw my weapon, my firearm. He is — he has the baton in both hands and he's — he's just swinging it back and forth towards Charles. He takes a step or two towards Charles. I'm ordering him to drop it. ... Giving him orders to comply. I shoot him twice. Subject drops."

Soeth then clarified that Newmaker was "aggressively swinging" the baton at Ellebrecht at "head height" when he shot him. But later in the interview, Hislop circled back and suggested a different chain of events.

"OK," Hislop started. "So, you shot two shots and — let's go back to that real quick. You shot two shots. ... He's doing this big overt swing toward Sgt. Ellebrecht. You shoot him. And then he falls down and he's getting back up again. And then you shoot him again?"

"After seeing the video, I — I believe that is what happened," Soeth answered.

"OK. Good," Hislop said, bringing the interview to a close.

Hislop's interview with Ellebrecht followed a similar course, with the sergeant saying Soeth fired back-to-back shots as Newmaker swung at him, after which the suspect fell to his knees, and Hislop then suggesting the second shot came later, as Newmaker was trying to get back up.

But neither version of events is what plays out in the video. The footage is hard to decipher but, at most, it shows Newmaker swing once at Ellebrecht, though it's unclear if the baton is ever in his hand from the footage. The autopsy results also tell a different story.

Performed by forensic pathologist Mark Super on March 20, 2012, the autopsy report describes injuries completely inconsistent with someone shot while standing upright by a shooter who is also standing, as Soeth undisputedly was. Specifically, Super describes the trajectory of one wound as entering Newmaker's lower left back just above his belt line and traveling upward, perforating his left lung and coming to a stop in his left pectoral area. The other bullet, according to Super's report, entered Newmaker's lower right back at the beltline and traveled upward into his heart.

Ronald O'Halloran, one of two forensic pathologists hired as an expert witness by Newmaker's family's attorneys, later opined that "the only reasonable ways for these bullet wound trajectories to occur ... are for Mr. Newmaker to be leaning forward sharply at the time he was shot or for him to be on the ground on his knees in a steeply forward-leaning posture, or to be prone on the ground."

Both pathologists' analysis of the wounds and the video footage conclude that almost 20 seconds elapsed between shots, with the second fired as Newmaker appeared to lay motionless on his knees.

During his interview, Soeth said he kept his gun trained on Newmaker until Ellebrecht ordered him to holster the weapon and begin administering first aid.

After the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling overturned a summary judgment dismissing a wrongful death lawsuit brought by Newmaker's family, the city of Fortuna opted to settle the case to avoid trial, paying out $900,000 to Newmaker's family.

If the Fortuna Police Department ever conducted an internal investigation to determine if Soeth had lied during its probe, there's no public record of it.

By the time Fortuna settled the lawsuit with Newmaker's family in 2018, Soeth had already moved on, hired as a deputy by then Humboldt County Sheriff Mike Downey in November of 2015. He'd also already been involved in another shooting.

In a July 9, 2019, letter clearing Soeth of any criminal wrongdoing in his second shooting, then Humboldt County District Attorney Maggie Fleming wrote that Soeth feared for his life when he opened fire on a July night two years earlier. Like the Newmaker case years prior, the letter is noteworthy for what it includes (that the suspect was booked into county jail for brandishing a firearm at a peace officer, for example) and what it omits (that said suspect was never charged with a crime).

Soeth, now a corporal, was working as a field training officer and was tasked with taking a new trainee — deputy Nathan Cumbow — on an orientation of the "40 Beat," a sprawling, rural swath of the county that runs east from Lord Ellis Summit to the Trinity County line, north to the Siskiyou County line and northeast to about halfway over Bald Hills Road, which Soeth had been working about a year.

It was a quiet shift, the deputies would later tell investigators, so Soeth decided to take Cumbow to some of the beat's outlying areas. At about 9:30 p.m., they met deputy Tismil Matilton at a gas station in Hoopa — Soeth later said he liked to bring an additional officer with him into these remote areas because if something happens, "backup is a long ways away." In two cars — Cumbow driving one, with Soeth directing him from the passenger's seat, and Matilton trailing in his own patrol vehicle — the trio made its way up State Route 96 out of Hoopa to Weitchpec before turning onto State Route 169 toward Martin's Ferry Bridge, which spans the Klamath River.

As Cumbow drove, Soeth pointed out landmarks and explained which roads lead where. It was shortly before 10 p.m. when they made it to Martin's Ferry Bridge, which sits on a remote area of the Yurok Reservation with no nearby housing or streetlights. They described conditions as "completely dark," with Soeth noting the moon "hadn't even risen yet." As they turned left onto the bridge, they noticed a black Corvette parked in the northbound lane with its parking lights on. Soeth decided to do a "vehicle investigation," illuminating the spotlights on either side of the patrol car and training them on the Corvette as they pulled in front of it.

George Richard Robbins III, a Hoopa resident, would later tell investigators he was working as a night watchman for Kapel Construction while sitting in his Corvette that night with his Pomeranian, "Baby," as he had every night for a couple months, keeping an eye on some heavy equipment the company had parked on both sides of the bridge. Robbins said he was "effectively blinded" by the headlights and spotlights pointed at him in the utter darkness of the night, and could not see who was approaching.

"There weren't any identification lights," Robbins later told investigators at the hospital. "I had no clue they were cops. It was just headlights and their floodlights right on me. I thought it was my cousin, fucking with me. He would pull up and do that sometimes."

So Robbins said he took a .44 caliber revolver from the back of his car and held it up in the windshield, at which point, "it was just like, boom, boom, boom." When the firing stopped, he said, he called out to stop shooting and followed officers' commands.

Soeth told investigators that as his patrol car pulled in front of the Corvette, its spotlights illuminating the sports car's interior, he saw a "silver revolver pointed directly at me."

"This looked like a big fuckin' gun," he said. "So, I yell, 'Gun.' ... and I bail out the — my side of the car. I stay low and I start runnin' to the back of the car, screaming, 'Gun,' knowing that deputy [Matilton] is right behind us."

Soeth said he got to the rear quarter panel of the patrol car, turned back and drew his firearm.

"I don't see the gun anymore," he told investigators. "I yell, 'Sheriff's Office, drop the gun. Show me your hands.' And the gun comes up again over the steering wheel. And I open fire on the driver's side of that Corvette, where I perceived that threat to be."

He repeated the description of events later in the interview when asked what would have happened had he not opened fire.

"I feel that that guy was going to shoot me given the fact that I had just given an announcement saying who I am and to drop the gun ... then the gun was presented again. I felt that I was going to get shot," he said.

Cumbow and Matilton, however, recalled things differently.

Cumbow, who was just five weeks into the job, working his 18th shift, when the shooting occurred, told investigators the patrol car was still pulling to a stop when he saw the gun come into view and heard Soeth begin yelling "gun," adding he then pushed the car into park, ducked down and tried to get out of his seatbelt.

"Before I could get my seatbelt all the way off, um, I heard firing," he said, adding that, seeing movement in the Corvette, he too stepped out of the patrol car and started shooting until he heard Soeth call out, "Red, red, red, red," having fired 16 times, emptying his clip.

Knowing the "red" call meant Soeth's gun was either malfunctioning or empty, Cumbow said he stopped firing but "stayed on target" to cover the vehicle while Soeth either reloaded or sought shelter.

"During the shooting, corporal Soeth was yelling, 'Hands, let me see your hands,'" Cumbow said. "And right after I stopped firing, I seen two — two palms come up in front of the windshield." Cumbow said he never heard Soeth identify them as deputies.

Matilton recalled things similarly, saying he saw Soeth exit the patrol car in front of him yelling, "Gun, gun, gun."

"His passenger door flew open and he was yelling gun several times," Matilton said. "Then he exited and within a split second, he was shooting."

The discrepancy is a potentially important one, as sheriff's office policy states that, where feasible, deputies "shall, prior to the use of deadly force, make reasonable efforts to identify him/herself as a peace officer and to warn that deadly force may be used." As such, the investigators tried to clarify.

"From the time you open your door to get out did you hear anybody, you know, say, 'Sheriff's department — police,' anything you know identifying yourselves as law enforcement" one asked.

"I did not," Matilton replied.

Investigators also asked Cumbow if he heard Soeth say anything after calling out the gun and the trainee said he heard him order Robbins to show his hands, but only after he started shooting. One of the investigators then asked if the situation was stressful and scary, and maybe that has caused Cumbow to forget some things. The trainee said he wasn't sure exactly when he turned his spotlight on, but remembered "everything else confidently."

In total, Soeth and Cumbow fired 22 shots into Robbins' Corvette but only one grazed his left shoulder. After the shooting, he crawled out of the vehicle, complied with orders, and was handcuffed and placed in the back of a patrol car while screaming in disbelief, "You shot me!" (Baby the Pomeranian was later found unharmed in the vehicle by an investigator.)

After Robbins was detained in a patrol car, Soeth went back to his vehicle to reload his gun and grab two extra magazines, handing one to Cumbow.

"We didn't know what was gonna happen next," Cumbow told investigators, adding the officers feared "somebody else was gonna come out shooting at us."

Nobody else came out shooting that night, though the incident did anger many on the Yurok Reservation, who felt the deputies should have notified tribal police before entering an area they rarely patrol and taken steps to more clearly identify themselves to Robbins.

In her letter clearing Soeth and Cumbow of any criminal conduct, Fleming describes the incident as a "misunderstanding." The letter presents Soeth's account of how things unfolded as fact, despite there being no video or audio recordings of the encounter to corroborate it and that it diverges from the recollections of Robbins, Cumbow and Matilton. "Corporal Soeth announced, 'Sheriff's Office, show me your hands!'" Fleming writes, though she later states Matilton "did not recall" hearing any verbal identification.

Fleming also notes that Robbins "claimed" he did not fire the gun at deputies and that a subsequent inspection of his gun "could not support or refute" the claim, though no one at any point alleged Robbins had fired a shot.

Robbins sued the county in the aftermath of the shooting, alleging unreasonable use of force, unlawful arrest and unlawful search and seizure of his property. On Oct. 11, 2019, the county settled the suit, paying Robbins $200,000 to avoid a trial while denying any wrongdoing.

Five months after Robbins' settlement, a pair of California Highway Patrol officers were driving northbound on U.S. Highway 101 near Hooker Creek Road when they noticed a Jeep Wrangler weaving in and out of the lane in front of them, and initiated a traffic stop. But the Jeep failed to yield, leading the officers on a pursuit that spanned almost 50 minutes but never reached speeds greater than 60 miles per hour and at times slowed to 25 mph, with the driver never taking any evasive actions or seeming to attempt to "lose" the police trailing them.

Multiple Journal attempts to contact the driver for this story were unsuccessful. (Police reports alternately refer to the driver with different gendered pronouns, so we will apply they/them pronouns in this story.) Comments later made to officers would make clear the driver was in the midst of some kind of mental health episode, delusional and convinced they were a CIA operative and Secret Service agent working directly for President Barak Obama, repeatedly saying officers didn't have the clearance to be told their mission.

Over the course of the pursuit, the driver pulled over multiple times but refused to exit their vehicle, each time pulling back on the road and continuing on before they could be contacted by officers. In one of these stops, they slowly backed their Jeep toward the pursuing vehicles before shifting it into drive and continuing on. It was a strange, prolonged pursuit, with the CHP officers calling it in as a misdemeanor while noting the driver wasn't taking any evasive actions or driving recklessly in any way.

By the time the driver pulled over for the final time on the shoulder near Shively Road, Soeth, then a special assignment canine officer with the sheriff's office, had joined the pursuit, responding to a call for backup.

The two dash camera recordings of the incident released by CHP to settle litigation brought by the Journal show what transpired next. Once the Jeep Wrangler pulled to a stop, CHP officers with weapons trained on the vehicle began ordering the driver to show their hands and exit the Jeep. The driver remained in the car but unzipped the Jeep's plastic driver's side window and put their hands out.

Soeth, meanwhile, got Yahtzee out of his car on a long leash and then, without saying much of anything to the CHP officers, commanded the dog in Dutch to jump into the car's driver's side window and attack the driver. (Soeth would later tell investigators he issued a verbal warning, "Get out of the Jeep or you're gonna get bit," but if he did, it's not audible in either of the two dash camera recordings and none of the other officers reported hearing it.)

Yahtzee then ran up to the driver's side of the Jeep and put his front paws on the driver's door, but appeared confused as the driver reached out in an apparent attempt to pet him.

The dog then ran back to Soeth, who continued issuing commands, then back to the driver's side door, and then around to the passenger side, all as CHP officers continue to order the suspect out of the car. The driver then complied, opening their door and stepping out of the vehicle. At this point, Yahtzee ran back toward them and Soeth again ordered the dog to bite. But again, the driver appeared to try to pet Yahtzee and the dog didn't bite, and instead ran back toward Soeth. As officers yelled for them to "get on the fucking ground," the suspect took three casual steps toward officers, their hands clearly visible, then began to lower themselves to one knee.

About the same moment the driver's knee touched the road, Soeth can be seen running into the frame and tackling them, after which the other five officers on scene descend to try to get them into handcuffs. After the officers rolled the driver onto their stomach, Soeth punched them three times quickly in the ribs, later saying it was an effort at pain compliance. The officers were able to control the suspect's left arm and get it cuffed but were struggling with the right. This is when Soeth again ordered Yahtzee to bite, and the dog did, clamping down on the suspect's right arm near the elbow, causing them to cry out in pain. In the video, the dog appears to have stayed latched on for about 27 seconds, only releasing when Soeth conducted the choke-off maneuver and physically lifted the dog from the ground and carried it back to his car.

When Soeth later wrote his police report of the incident, he omitted the fact he'd punched the suspect in the ribs — a violation of policy, which requires all uses of force to be documented. Soeth also neglected to note that the suspect was being held down by five officers at the time he commanded the bite. After being notified that the CHP had video of the arrest and it was inconsistent with his report, Soeth wrote a supplemental report that documented his punches to the driver's ribs.

On April 12, 2020, Sgt. David Diemer wrote a memo to his supervisor, Lt. Gregory Musson, detailing his review of the use of force, which included interviews with Soeth and the other officers at the scene. The officers' takes on the situation varied, with two saying the dog bite was justified and the dog was under Soeth's control, and two saying they felt Yahtzee was out of control, including one who also said deploying the dog was unnecessary. It seems things may have ended there had CHP Lt. Ben Fillman — now serving as the agency's Williams Area commander — not brought a complaint.

That complaint is referenced in the internal affairs investigation but not included in documents released to the Journal, and Fillman declined an interview request, so its exact content is unclear. But it was enough for the sheriff's office to take action, suspending Soeth and his canine from field work and launching an internal affairs investigation in June of 2020.

The investigation, assigned to then Lt. Peter Cress, examined six potential violations of department policy. However, only two — unreasonable use of force and exceeding lawful peace officer powers by unreasonable, unlawful or excessive conduct — were deemed publicly disclosable under state law. The other alleged violations of policy and the findings associated with them are redacted in the documents released to the Journal.

When interviewed during the investigation, Soeth was adamant that his conduct at the scene was appropriate and his use of force justified. He told investigators he believed it was — and should have been — classified as a felony pursuit. This is a key point under department policy, which requires handlers to take into account the "nature and seriousness" of the suspected offense and only deploy the dog if a suspect has committed a "serious or violent" offense and either poses an imminent threat of violence, is physically resisting arrest and the canine "reasonably appears to be necessary" to overcome the resistance, or the suspect is hiding somewhere that it would be dangerous for officers to enter.

Asked why he felt it was a felony pursuit, Soeth noted its length and said the driver was weaving at times. He also pointed to the driver having backed up toward officers' cars, saying he took that as a threat. And had he not deployed Yahtzee, Soeth said the unsearched suspect could have produced a weapon from their waistband, flailed and injured an officer or escaped all six officers on scene and gotten back into their car to flee, posing a danger to the community. The CHP, Soeth said, should have treated the case as a felony committed by a potentially impaired suspect rather than a misdemeanor by someone in a state of mental health crisis.

"I think had this gone to the DA's office, like, with real charges, I ... would hope that the sheriff would support me more on my actions, but I think, uh, the CHP dropped the ball on their end and the metaphorical bus is runnin' me over," he told investigators, when asked if he had anything to add.

Interviews with the other officers, as seems to be a pattern with Soeth's use of force incidents, paint a different picture. While they at times appear reticent to criticize Soeth's conduct directly — with all the CHP officers noting they have no experience working with police dogs — it's clear that none perceived the level of threat Soeth said he did and none believed the individual involved was aggressive.

Deputy Kellen Brown described the suspect as appearing "confused," while officer Brian Evans described them as "kind of meandering" and officer Neil Johnson described them as seeming "kind of lost." Officer Jose Maldonado used the words "lackadaisical" and "slow moving." Officer Kevin Wills said the suspect was "uncooperative ... but wasn't trying to fight us."

"She seemed overly relaxed," Evans told investigators. "I mean, she was trying to pet the dog."

The other officers also all agreed that the suspect, after Soeth tackled them to the ground and the other five officers joined the fray — was tense and noncompliant, but not violent. They all agreed the threat was minimal.

"She was pretty tight — um, naturally. I probably would be, too, if I had a dog latched onto me and six people on top of me," Brown said. "Based on how many officers we had, there wasn't a very high risk."

When Cress' investigation was finished, its findings would become a point of contention within the sheriff's office. Musson and Capt. Brian Quenell felt the incident looked like "crap" because the use of force "even justified, is often violent in nature," according to an inter-office memo, and felt additional training would be warranted. Musson later advised Soeth that his report writing after the arrest was "unsatisfactory" and discussed what his "tactical role should have been versus what it was." But neither felt Soeth had violated policy.

The case then went to Undersheriff Justin Braud for an executive review in January of 2021. Over the course of nine pages, Braud details various opinions on the case, noting, "It is hard for me to believe that, even if lawful, the use of the K9 to retrieve the other arm, with all the other resources available, was the most reasonable use of force in that situation."

Ultimately, though, Braud opined that discipline was not warranted in the case and that Soeth should keep his police canine duties, "but with a new emphasis of responsibility and accountability expected of him." Departmental policy, Braud wrote, should also change to ensure more oversight of the canine program.

But when it came time to decide Soeth's fate, Honsal diverged from his command staff, notifying Soeth on April 2, 2021, that he intended to suspend him for 40 hours. Honsal's analysis makes clear he found Soeth's deployment of the dog "unreasonable."

"It is my determination that you escalated the situation, and the deployment of the [police services dog] was not reasonably necessary due to the overwhelming force of officers on scene," Honsal wrote. "The evidence shows that all six law enforcement officers on scene had control over this incident when the driver was on the ground. The use of the PSD was not justified because the torso, arms and legs were already being controlled."

Honsal further wrote that Soeth's police report failed to document his punches to the suspect's ribs and made it sound "like you were wrestling with the driver alone when the bite was initiated."

At a Skelly hearing — an opportunity for an officer to plead their case before final discipline is meted out, as guaranteed under the California police officer's bill of rights — Soeth appeared with attorney Julia Fox, a partner with the high-powered law firm of Rains Lucia Sterns, which contracts with police unions throughout the state. She walked in with an air of confidence.

"I have to tell you candidly, sheriff — not being cute — I really don't know why we're here on that case," she said, according to a transcript, noting Honsal's executive team has said "this is on the up and up when it comes to policy."

She then pointed specifically to Braud's review, saying, "I think, frankly, were this to go to arbitration, I would probably just plagiarize a lot of the points that he made. He teed up the argument for me."

Ultimately, Fox's assessment was persuasive and in a final notice of disciplinary action issued July 26, 2021, Honsal reduced Soeth's punishment to a written reprimand.

"I recognize that there are differences of opinion in this investigation," Honsal wrote. "And to be frank, those conflicting differences make it difficult for me to impose major discipline. ... You should take this as a severe warning regarding your conduct with future use of force actions."

Asked if her office's prosecutors ever considered filing an assault charge against Soeth related to the dog bite, now District Attorney Stacey Eads said it did not.

"The video was not reviewed by the district attorney's office for that purpose nor was a law violation by an investigative law enforcement agency made to our office in connection with Mr. Soeth's deployment of the canine," Eads said.

The suspect in the case, meanwhile, was deemed mentally incompetent to stand trial and ordered to undergo treatment. After almost two years, "a mental health expert concluded it was doubtful [they] would ever regain competency," Fleming wrote in an email to the Journal, adding that as a result her office had dismissed the misdemeanor failure to yield charge filed against them.

Twelve days after Soeth ordered Yahtzee to bite that driver on the side of U.S. Highway 101, his ex-wife picked up their 6-year-old son from his care. On the drive home, the boy told her something that alarmed her. According to court documents, he said his dad had caught him telling a lie and, as punishment, punched the boy in the face twice and spanked him four or five times.

The corporal punishment, Soeth's ex would allege in court filings, left bruising on the boy's left cheek and "covering much" of his buttocks, saying the bruising on his cheek remained visible for almost two weeks, while the bruising on his backside subsided after five or six days. She also alleged the boy said Soeth had previously threatened to punch him or "shoot" the television in response to bad behavior. (Soeth, for his part, never denied the allegations in the court filings.) Soeth's ex reported the incident to the sheriff's office, which would conduct a criminal investigation and ultimately submit a report to the Humboldt County District Attorney's Office recommending Soeth be charged with a misdemeanor violation of Penal Code 273a(b), or inflicting "cruel or inhuman corporal punishment" on a child. But instead of charging the case, on May 18, 2020, the district attorney's office offered Soeth a pre-charging diversion agreement, saying that while it believed he had committed the crime it would agree not to file the charge if he successfully completed a parenting course and received mental health counseling. Soeth agreed to the terms and completed the agreement in February of the following year, so no charge was ever filed in the case and — absent Soeth's ex referencing it in family court filings — it may never have become a part of the public record. Soeth's ex declined to be interviewed for this story.

Fleming, the district attorney at the time, told the Journal she felt the agreement was appropriate in the case because "isolated incidents of parents slapping or spanking their children over their clothes — as in this case — are generally not considered physical abuse," and her office doesn't generally charge such cases. But in this instance, Fleming said, she saw "an opportunity to encourage improvement in a law enforcement officer's future interactions with both his family and possibly the public and the officer agreed to participate in the parenting class."

Two experts in child abuse prosecutions told the Journal that the outcome in the case seemed appropriate based on best practices — taking into account the absence of any prior abuse allegations and the potential trauma involved in a young boy testifying against his father — though they said Soeth's status as a police officer who regularly works with the district attorney's office posed some challenges, both optically and logistically.

This became apparent June 14, 2021, when then Deputy District Attorney Jane Mackie walked into court on a drug case she'd been handling that had been filed almost a year earlier and asked to speak privately with the judge in an in-camera hearing. She told the judge it had "come to her attention" a few days earlier that Soeth — a witness in the case, as he'd been handling Yahtzee when the dog reportedly found more than 2 pounds of suspected heroin in the defendants' car — had recently completed a pre-trial diversion agreement with her office, a matter that may warrant disclosure to defense attorneys.

Superior Court Judge Kaleb Cockrum ruled the agreement should be turned over to the defense, saying the child abuse charge constitutes an "act of moral turpitude" legally, which could reflect on a witness' credibility. Additionally, he said, the pre-charging diversion agreement (which he described as "uncommon" and Fleming said were reached in about a dozen cases a year in her office) would constitute the witness having received a "benefit" or a "deal" from the district attorney, which the defense has a right to know. Mackie then turned over the diversion agreement to defense attorneys in the case, including current Public Defender Luke Brownfield, who said it was the first he became aware of it.

And it appears Mackie only became aware of the agreement because the Journal had started asking about it a couple months earlier.

"Here is the packet that was sent to the North Coast Journal," Fleming wrote in a June 11, 2021, email to her deputy prosecutors, forwarding the documents released in response to a Journal public records act request. "I have discussed the issue with [Eads] and we agree the best path would be for us to provide the materials (not our letter to NCJ but the documents sent to him) to the judge in each case Soeth is called to testify and leave it to the court whether or not it is disclosable."

Eads, having now taken over for Fleming, told the Journal that Soeth was involved as an arresting officer or potential witness in 22 cases the office handled between May 22, 2020, and June 11, 2021.

She said Fleming's email was "neither the first nor only occasion" the office's prosecutors were made aware of the agreement involving Soeth, but said she found no other emails documenting such advisements. And according to the transcript of the hearing in the drug case, Mackie makes clear she had only just learned of the agreement that had been reached 13 months earlier and its relation to a case she'd been handling for nearly a year.

Brownfield, for his part, said it does not appear his office was notified of the agreement in five cases it handled involving Soeth, though he said a subsequent review found the nondisclosure would not have affected their outcomes.

Informed of the findings of the Journal's broader investigation into Soeth, Brownfield said a documented pattern of dishonesty in internal affairs investigations would absolutely warrant his office revisiting cases in which Soeth was a principal witness.

"Yes, if he's being dishonest, especially on the record, then we're going to review all the cases he's been involved in," Brownfield said.

There's a saying in law enforcment, "If you lie, you die." It's meant to underscore the importance of honesty in a profession in which your word alone can result in someone's arrest. As such, the requirement for honesty in report writing and investigations is written into departmental policies and even case law, with a state court of appeal noting in a 2019 ruling upholding a deputy's firing for lying, "dishonesty is incompatible with the public trust."

It's also why sustained findings of dishonesty are included in recent California transparency laws that open certain types of police personnel records to public inspection for the first time, adding them to the likes of cases involving deadly uses of force, excessive force and sexual assault committed on duty.

Records requests seeking sustained findings of dishonesty involving Soeth submitted to both the sheriff's office and the Fortuna Police Department indicate none exists.

Senate Bill 2, which went into effect Jan. 1, created a process to decertify police officers throughout the state for serious misconduct, including acts of dishonesty. In fact, of the 23 police officers decertified to date in the state, five were for dishonesty. But the system depends largely on reviewing the findings of local agencies' internal affairs investigations, which are now required to be turned over to the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training for review. POST will also accept complaints from the public about allegations of police misconduct, but generally just refers them back to the employing agency for investigation, though the law does give POST the authority to "conduct additional investigation," as necessary.

Under a provision of the new law, the sheriff's office will have to turn over all cases involving complaints or findings of series misconduct that occurred between 2020 and Jan. 1 of this year — which should include Soeth's dog bite case — for review by POST by July 1. Sheriff's office spokesperson Samantha Karges said the department is aware of the deadline and "working diligently" to gather the records for POST.

Speaking to the Journal in 2021, after an arbitrator had overturned the firing of a sergeant accused of sexual assault in 2014 despite the county spending more than $240,000 in legal fees fighting the appeal, Honsal voiced support for the new decertification law. He said he believes police chiefs and sheriffs should have more leeway to fire problem officers than the law currently allows.

"If we identify a law enforcement officer who has moral issues, integrity issues or racist issues, a law enforcement executive should be able to fire those people so they don't carry a badge and don't carry this awesome power afforded to peace officers," Honsal said, adding that because he doesn't have that leeway, he supported a statewide decertification process. "Trust in law enforcement is so important."

In that same interview, Honsal also spoke to the need for honesty and personal accountability generally, and in internal affairs investigations specifically.

"I tell my people when they get hired and I reinforce this, 'People are going to make mistakes. Deputy sheriffs are going to make mistakes,'" he said. "I don't expect perfect. All I expect is honesty."

In July of 2021, Honsal stripped Soeth of his canine handling duties and assigned him to serve as a bailiff at the courthouse. Asked about the changes, Honsal said he has the ability to reassign someone "based on the needs of the department."

"There's a lot of trust in these [canine handling] positions, so we have to make sure we have the right deputies in them," he said.

But Soeth returned to patrol about six months later under a provision of deputies' contract that allows them to choose shifts based on seniority. Honsal said he could have overruled the switch and permanently assigned Soeth to the courts but did not.

"There were no restrictions and, to be honest, I wasn't following it closely," Honsal said. "He opted to go back to patrol."

It's unclear if the sheriff's decision to strip Soeth of canine duties and temporarily place him in the courthouse was related to Soeth's having ordered Yahtzee to bite that driver or something else. He was also disciplined for an unrelated matter around the same time — suspended for 60 hours sometime between April and July of 2021, according to documents released to the Journal — but it's unclear for what. Court filings indicate an internal affairs investigation was conducted regarding the child abuse allegation, but related documents — if they exist — would be considered confidential personnel records.

Whatever the reason for the suspension, stripping a deputy of canine handler duties is not typically a decision made lightly. Departments invest heavily in training handlers and dogs as a team. In the sheriff's office's case, that means sending both to an initial five-week training in Santa Rosa, as well as quarterly "refresher" trainings. Changing handlers means starting that process over, at a cost of more than $10,000.

"It's an investment," Honsal said, adding that the dog and their handler also become ambassadors for the department, going to schools and community organizations. "It's an extremely expensive investment to train a canine and handler."

There's also the bond forged between dog and handler, as the officer takes their canine home when their shift is over and the animal becomes a part of their household, and their family.

"The handler's personality will go right down that leash," Burwell, the expert witness, said of police canine handlers generally. "If the handler's an idiot, the dog will be, too. The poor dog doesn't know any different. He just knows what he was told to do and what he was trained to do."

Yahtzee, meanwhile, remains in the field, now working under the handling of deputy Hal Esget. The dog, apparently, never lost Honsal's trust. Even that driver whose right arm Yahtzee bit three years ago and held for almost 30 seconds never held anything against the animal.

"The dog," they told investigators at the hospital while being treated for the bite wound, "did an admirable job."

Thadeus Greenson (he/him) is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at (707) 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected].

more from the author

-

Deputy Shoots Cutten Shooting Suspect

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Officials Weigh in on SCOTUS Case's Local Implications

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Arcata Lowers Earth Flag as Initiative Proponents Promise Appeal

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023