Woo-Woo and the Hammer

ResolutionCare and its mission to revolutionize the system

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The weekly staff meeting begins with the ringing of a Tibetan prayer bowl. ResolutionCare's entire staff — social workers, administrators, nurses, community health workers, clinicians, a chaplain, an "office synergist" and an IT specialist — crowd around a pair of tables pushed together as if a few people showed up unexpectedly for Thanksgiving dinner. Other employees video conference in from Mendocino, Del Norte and Shasta counties. Someone lights a candle and passes it around, inviting everyone to "check in" as waft of smoke drifts around the homey open floor plan office crammed with desks and computers. With the candle passed, someone takes out a stone — a small river rock with a hole drilled through it that's tied to a string — rubs it and begins passing it around the table. The stone represents a current or former ResolutionCare patient who died that week and each staff member takes a moment to rub it in his or her hands, to feel its weight and to share a remembrance of or a lesson learned from the recently departed.

"By the time the stone gets all the way around the room, it's warm to the touch," says Michael Fratkin, a palliative care doctor who launched ResolutionCare in 2014 searching for a healthcare model that better cared for patients and staff alike. "The next step of the meeting is we offer a poem or some such reflective stuff, a reading, a quotation, whatever. Then, we switch the meeting to an all-aboard operational meeting. But as we make that switch, the candle remains lit and the sacred space of honoring each other, of listening and respecting each other — we keep that sacred space open to connect the kind of woo-woo spiritual stuff we're doing with the practical hammer swinging."

Another ringing of the Tibetan prayer bowl calls the staff meeting to a close, after which the staff returns to ResolutionCare's mission of "bringing capable and compassionate care to everyone everywhere in the face of serious illness."

At the center of ResolutionCare and its ritualized staff meetings stands Fratkin, a softspoken yet talkative man who can be seen as some kind of amalgamation of guru, savant, physician and insurgent. To hear those around him tell it, Fratkin has a unique ability to inspire people, to empower them to be their best and to embrace the possible. There's a magnetism about him, they say.

Take ResolutionCare chaplain Carl Magruder, who was driving to work in the Bay Area one day when he heard NPR interview Fratkin and said he instantly wanted to work for the man.

"I said to myself, 'If that guy ever needs a chaplain,'" Magruder recalls with a laugh. "He's an iconoclast, someone who shatters molds."

When ResolutionCare launched in 2014, it consisted of little more than Fratkin, a community health worker and some furniture they'd brought from home and stuck in an office space donated by Wahidulluah Medical Corp., which owns Redwood Urgent Care. A bit more than four years later, it has three dozen or so employees and serves almost 200 patients in four counties.

In Fratkin's eyes, the rapid expansion underscores the need for what ResolutionCare offers its patients and staff: intensely personalized care and a collaborative, nurturing work environment. Both were born of Fratkin's own professional burnout.

Now in his mid 50s, Fratkin got a medical degree from Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland before coming to Eureka's St. Joseph Hospital in 1997 to practice palliative care, defined as a treatment that relieves or lessens pain and negative systems without necessarily attacking their causes or seeking a cure. It's similar to hospice but differs in that hospice is limited to patients with terminal diagnoses and less than six months to live who have ceased any curative care, while palliative care is more open. While it is limited to those with serious and often terminal illness, palliative care patients need not ceased other treatments to qualify.

Palliative care can be seen as a collision of health and wellness, where a patient with a dire health prognosis is empowered to find a sense of well-being as they live out their final days, months or years.

Here's how Fratkin describes his approach to new patients: "I let them know who I am and explore who they are. I help them understand the totality of their circumstances. I identify with them what's most important to them, what matters to them given all the things that can't be changed or can't be known about their future course. Then, I roll up my sleeves and let them tell me what my job is."

But as Fratkin entered his second decade on the job, his frustrations mounted. He increasingly felt palliative care's goals — empowering patients to set their own priorities, to chart their own course — conflicted with a "siloed, commodified, transactional" healthcare system designed to cure ailments but not necessarily to treat people. And within that system, Fratkin says he began to burn out. He found himself at odds with other physicians, increasingly isolated, feeling an ever-growing pressure on his shoulders.

"I'm not alone," Fratkin says, pointing to studies, like one from the Mayo Clinic in 2015, showing that more than half of the nation's physicians and nurses show signs of burnout. "Everyone's a widget, everyone's a gear grinding against the messy experience of human existence, so patients aren't getting what they need and people inspired to help people, to show up for people, are being burned out."

Asked what that looked like for him personally, Fratkin says if you asked people around him at the time, they'd say he was surly, ego-driven and frustrated, but he says he often just felt sad and depressed. He felt there had to be a better way, both for patients and those caring for them.

ResolutionCare Operations Director Amy Bruce and nurse Lauri Rose are sitting at the office's conference table, which is really a repurposed dinning room table from someone's home that now has a black, skull-clad runner down its center anchored by a poinsettia plant. Both have spent decades in health care, Bruce most recently as an administrator at Planned Parenthood and Rose as a nurse at Redwood Memorial Hospital, a hospice volunteer and with Southern Trinity Health. And both came to ResolutionCare precisely because it was trying to do something different.

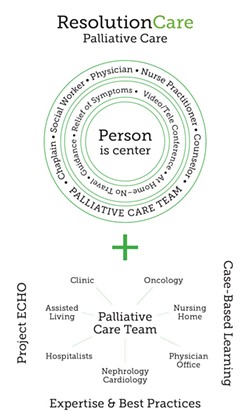

They're trying to describe a day in the life at the office. At the core of ResolutionCare's work, they say, are interdisciplinary teams consisting of a nurse, a provider, a social worker, a community health worker and a care coordinator who are assigned to patients. The teams meet and discuss every aspect of a patient's care and how to best meet his or her priorities. To hear Bruce tell it, a lot of the work is about helping patients manage and navigate their care, making sure it fits with their goals and desires.

It's important to remember, Bruce says, that a lot patients aren't familiar with the systems that come to dominate their lives.

"For a cancer patient, it's like you're dropped on Planet Cancer," she says. "You're supposed to know how to do cancer but you don't."

So the team helps its patients navigate the new terrain and the ways it intertwines with and disrupts other aspects of their lives. A lot of ResolutionCare's patients are low-income, qualifying for the company's services through a relatively new law requiring that Medi-Cal cover in-home palliative care for qualifying patients. Consequently, a lot of the teams' work revolves around helping patients deal with housing and food insecurity, and getting the little things that they can't afford but would improve their quality of lives.

For Don Brown, who spoke to the Journal last year, relaying that he'd found ResolutionCare after suffering five pulmonary embolisms, two strokes and 18 deep vein thrombosis, in addition to having a fully clogged artery in his heart, that mean getting him a lounge chair in which he could recline and elevate his legs, taking pressure off his delicate veins. For other patients, it's finding them the walker insurance won't cover. For one woman who was working full-time until recently being diagnosed with a serious heart problem, it meant helping her sign up for food stamps, general relief and long-term disability. It means picking some patients up and taking them to appointments, or repeated calls to remind them to take their medication.

Bruce says a lot of people might wonder why it should be a healthcare provider's job to cajole people into keeping up with their medication regimens. She counters that keeping patients healthy is inherent to their mission and that it reduces overall costs to the system.

"If we don't help a patient take their pills, they're going to end up in an ambulance and the emergency department," Bruce says flatly. "That's the other option."

And while ResolutionCare's model centers around in-home video conferencing, allowing clinicians to check in with patients regularly without disrupting their lives, much of the team's focus is on the non-medical aspects of having a serious illness. The focus, they say, is often on helping patients make informed decisions and live their best lives.

That takes some unusual forms. Rose points to one patient who for years has collected recyclables for a living — plucking them from dumpsters and trash cans and collecting them to take down to the recycling center. The man didn't have a car and had gotten too sick to haul the recyclables to the center himself. But recycling had become part of his identity and the piles of bottles and cans around him were causing stress.

"This is who he is," Rose says, "so we're going to figure out a way to help him get that recycling to the center."

Another guy wanted to spend as much of his limited time in this world fishing. "So," Rose says, "sometimes we went and met him at the river."

Magruder, the chaplain, recalls taking a man who'd grown up on a farm to the local petting zoo to give him a taste of his childhood, taking another guy to ride on a train. Then there was the woman who'd been bedridden inside her small trailer for years.

"We arranged for her to be strapped to a gurney to go out in her front yard to feel the sun on her skin," he says, pausing a moment to reflect. "Healing is available even when a cure is not. ... pain is inevitable, perhaps, but suffering is optional. From a spiritual standpoint, it comes back to healing. There are people (in our care) who are more well than they have ever been, more full of gratitude, more free of fear, more full of forgiveness in their personal relationships."

Having been a part of ResolutionCare for a couple of years now, Rose says it's clear to her this is a model to follow, not just in palliative care. After all, if this can be done for the seriously ill and dying, why shouldn't it be done for pregnant mothers, children and families?

"This is just good medicine," she says, referencing medical care that wraps around people, seamlessly integrating their care with the rest of their lives. "This is what everyone wants."

Fratkin is posing for a picture, sitting in a teleconference room tucked in the back of the ResolutionCare office. There's a custom-made wood bench shaped in an arch, which lets multiple team members conference with a patient. Bamboo erupts from a pot in the corner next to a meditating gnome statuary. The back wall is covered in blue wallpaper with fluffy white clouds. Fratkin asks the photographer to make sure a B Corp sign makes it into the shot.

The B Corp certification is a point of pride for Fratkin. The nonprofit B Lab certifies for-profit companies as B Corps that meet certain standards for environmental performance, accountability and transparency, somewhat akin to a Fair Trade stamp for coffee. A big part of the reason ResolutionCare qualified for the designation is its approach to taking care of its employees — whom Fratkin says he prefers to refer to as "co-workers."

There are a host of ways the company strives to care for its caregivers, Magruder says. There's the measurable stuff — it offers competitive pay, insurance and retirement benefits, counseling services and the flexibility to work around family demands. But just as important, Magruder says, is its democratic, team-based approach to the work that makes it truly unique in health care.

Magrduer recalls a time early in his tenure at ResolutionCare when he and a community health worker went over to St. Joseph Hospital, where a patient was receiving chemotherapy, to have him fill out some enrollment paperwork. It didn't go well. The room was loud and bustling, making it hard to have a conversation.

"We came back to the office and Michael was sitting at the table," Magruder says. "The community health worker just said, 'I'm never going to have that kind of conversation with someone in that setting again. I'm not doing it.' Michael just said, 'I hear you. Let's not do that again.'"

Magruder was blown away, saying that type of exchange doesn't happen with doctors in other settings.

"It's a hierarchy like the military," he says. "The private does not come up to general to say we should not go up that stream bed. It doesn't happen. But this is a pretty great place to work."

ResolutionCare is different, Magruder says, adding that when doing an in-home visit with a patient, he won't hesitate to reach out to the clinician if the patient seems in pain or in need of help he as a chaplain can't provide.

And with that collaboration comes support, Rose says, adding that team members can lean on each other or brainstorm solutions together.

"In this business, having that level of support is a really, really nice feeling," she says. "It's also naturally collaborative and I can say, 'No, I can't take on any more,' and that's honored."

Part of what enables all this, Magruder says, is that ResultionCare is new, allowing teams to explore solutions "based on our values and intentions, how to do this best rather than how to follow a huge list of rules."

But the company has also grown exponentially, fueled by changes to Medi-Cal that cover in-home palliative care benefits and contracts with two other insurance providers. For Bruce and Fratkin, that growth has proven challenging to manage on the fly while maintaining the company's loftiest ideals.

Reflecting back on where he was five years ago, Fratkin says he's happy. His work is fulfilling and nurturing. He feels good about the care his company is providing and the way it has empowered his co-workers to do their best work.

But he admits he personally has some work to do on the self-care side of things as he tries to bring his health and wellness into balance.

"I need to get to a place where I'm not working a million hours a week, not drinking 5 gallons of coffee every morning and not getting fat from eating bad food fast," he says. "I need to get to a place where I'm working out, feeling physically fit and doing all the stuff our team members are doing."

Back at the conference table, Bruce sits below the branch of a Manzanita tree that hangs from the ceiling, dubbed the spirit tree. Attached to it are more than a hundred of those river rocks, hung to honor and remember the deceased. Two other branches loom over other parts of the office, visible reminders of not only the lives ResolutionCare has touched but also the intentional nature of the company, the way it approaches people.

"It's a B Corp thing but it's also built into the DNA of the organization and the people here," Bruce says. "It's wonderful being in a place that's just trying to do the right thing, all the way around."

Thadeus Greenson is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Speaking of...

-

Resolution Care Sells to Healthcare Tech Company in Merger that Could Lead to National Expansion

Jun 4, 2021 -

Grief When the Losses Mount

Apr 29, 2020 -

Into an Unknown Wilderness

Mar 26, 2020 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

more from the author

-

Deputy Shoots Cutten Shooting Suspect

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Officials Weigh in on SCOTUS Case's Local Implications

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Arcata Lowers Earth Flag as Initiative Proponents Promise Appeal

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023