What Now?

Two men, 20 minutes and the fracture in Arcata

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

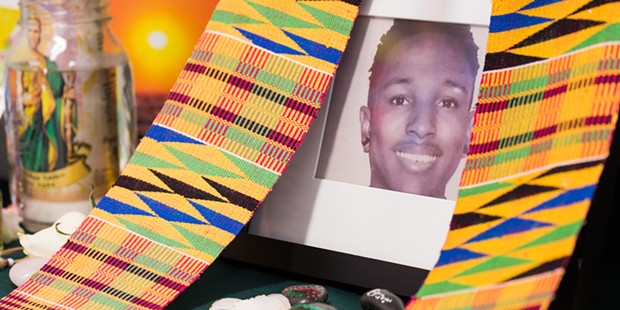

David Josiah Lawson's mother's grief is audible as she speaks with her Jamaican accent. But so is her pride. She's in KHSU's studio talking to a radio DJ just a few days after her 19-year-old son was fatally stabbed at a house party. She explains her son's childhood love of green-apple Jolly Rancher candies and how he'd ask his grandmother to make curried goat and rice and peas when he came home from school.

Michelle-Chermaine Lawson says her son was almost always smiling — a statement later echoed by his friends. In an interview a few days later with the Journal, Katauri Thompson, an HSU freshman, says the college sophomore's grin was so powerful that he would sometimes sit in front of people who were angry or sad, grinning at them until they cracked and reciprocated. On the radio, Lawson's mother also notes that her son always had to make sure he was looking good. You'd never find a bit of dust or lint on him, Thompson agrees, like he kept a hidden stash of lint rollers. "He'd stop and lick his finger to wipe dirt off his shoe," Thompson says. "He was squeaky clean, boy. He would make you recognize all the things you could do better."

Michelle-Chermaine Lawson talks about how her son had a way of getting things done, of setting goals and achieving them. He decided he wanted to run track and eventually qualified for the junior Olympics in the long jump. And when she — a single mother — told him going to college wasn't an option, he got the grades to get into Humboldt State University and tirelessly cobbled together the scholarships to pay for his education.

About 11 miles south and a couple of days later, Eric Zoellner — father of Kyle, the 23-year-old McKinleyville man charged with Lawson's murder — answers the phone sounding exhausted. He, too, has layers of grief in his voice. "None of this makes sense," he says. But asked to talk about his son, his voice changes as he describes an introverted young man — "the definition of a home body," he says — who works hard at his job as a chef for a catering company and grew up in local churches.

Kyle Zoellner has always been bright, his dad says. In seventh grade, he was taking geometry classes at the high school. A few years later he was frustrated that his high school didn't offer calculus. "He just went and got a calculus book and started teaching it to himself," Eric Zoellner says with a chuckle, before gushing about his son's love of music, from the days when he played trumpet in the Eureka High School jazz band to his current fixation with making electronic music in his makeshift home studio.

Friends of Zoellner, all of whom declined to be named talking publicly about him, say he's just a humble, working class guy. He's friendly, they say, with a reserved but sharp sense of humor.

These are the two men — David Josiah Lawson, 19, and Kyle Christopher Zoellner, 23 — who are the center of the case that's fracturing Arcata. It's a case that is rife with racial tension: Lawson is black and Zoellner is white. It's also one that is laying bare that a division exists between Humboldt State University and the community that surrounds it.

In the hours and days after Lawson's death, a narrative has emerged — a theory of the case — which holds that because of his race, Lawson was accused of being a thief, stabbed and then left to bleed out in the mud as prejudiced or incompetent first responders stood by.

But nothing about this case is clean, nothing about it seems to fit neatly into a narrative. Of the dozens of news reports about Lawson's killing, none contain an eye witness account of the stabbing. Similarly, at a party reportedly attended by more than 100 people, not a single video or photo has surfaced of the stabbing or even the fights that surrounded it. Meanwhile, witnesses contend that Zoellner was badly beaten at the party — which his jail booking photo seems to confirm, though it's unclear how much of that damage was done before or after he is alleged to have stabbed Lawson.

As the Journal goes to press, a court hearing to determine if there's enough evidence to hold Zoellner to stand trial for Lawson's killing is ongoing, providing the public with the first full vetting of the evidence police have collected in the case. In the weeks since Lawson's death, the Journal has interviewed more than a dozen people — partygoers, friends of the deceased and the accused, first responders and neighbors of the home where Lawson was stabbed at around 3 a.m. on April 15. The result is the following timeline, offering the public its most complete look yet at what happened immediately after Lawson fell to the ground with two stab wounds — one to the ribs and one to the upper abdomen — on a dimly lit cul-de-sac off Spear Avenue.

3:02 a.m.

The first 911 call comes into the California Highway Patrol dispatch center, reporting a disturbance in the 1100 block of Spear Avenue. A flurry of calls follows, one on top of the next, reporting a stabbing.

The party had been going for hours at the beige home with green trim at the end of a short driveway. Estimates vary, but it seems between 100 and 150 people were there, including a contingent of more than a dozen members of the HSU club Brothers United, whose members describe it as an inclusive club formed about a decade ago to help give students of color a safe haven and a feeling of belonging as they transition into adulthood far from home. The group had been celebrating a birthday at Bayfront One in Eureka before coming to the party, where a Brothers United member was supposed to be DJ-ing.

One neighbor said the party had been steadily escalating since about 1 a.m., noting that he'd considered calling the cops earlier to break the thing up. At about 3 a.m., he says he heard "a girl screaming like crazy." Clearly fed up with the college students having intruded on his neighborhood, he says the party and stabbing were the result of "stupidity, alcohol and entitlement."

Meanwhile, Arcata Police Chief Tom Chapman said a single dispatcher was trying to triage all the 911 calls.

3:03 a.m.

The first officer arrives on scene. A neighbor interviewed by the Journal said he returned home right as the officer pulled up, and watched the scene unfold. "It was like something you see in a movie — people yelling, 75 kids everywhere, girls crying and screaming and shit," he said, declining to be identified discussing the case.

Zoellner, he says, was sitting over in the first driveway off the cul-de-sac, with his girlfriend and a couple other people nearby. "He was just slumped," the neighbor says. "The picture didn't even do it justice. His face was mangled."

Chapman says the first officer responding to a call like this is tasked with scene assessment, essentially figuring out "what do we have and how do we respond to it." In this case, Chapman says the officer "did encounter a really chaotic, dynamic scene. As the officer's coming in, cars are leaving and people are flooding out."

As the officer's getting out of his car, Chapman says he "immediately encounters people who are hysterical and he's directed to a person that is being detained or being held and that ultimately was Zoellner, who was being identified as the person responsible for the stabbing." The officer immediately "intercedes" and takes Zoellner from the group, Chapman says, finally placing him in the back of his patrol car.

3:04 a.m.

A second officer arrives just as the first officer radios to dispatch that there's a fight in progress with about 100 people on scene. Around the same time, dispatch receives a 911 call reporting a fight with a knife and possibly a gun.

3:05 a.m.

A third officer arrives on scene. Meanwhile, Chapman says, the first officer on scene is still with Zoellner at his patrol car, standing guard. "Unfortunately, people from the crowd tried to get to the car," Chapman says. "They were banging on the windows with the appearance that they were trying to get at Zoellner. The officer could not disengage with that situation."

At the same time, a tone sounds at the Arcata Fire Department notifying personnel that a medical aid call is coming in, according to Chief Justin McDonald. The fire chief said there's a bit of a delay in notification because medical response calls are channeled through the Cal Fire dispatch center before being passed on to local crews.

3:06 a.m.

Arcata police advise dispatch that medical personnel are cleared to enter the scene as soon as they arrive. When there's a call for medical aid to a potentially violent scene, it's customary for first responders to stage nearby until getting word from police that the scene is safe to enter. According to Chapman, McDonald and Arcata Ambulance CEO Doug Boileau, this call was made within about four minutes of the first officer's arrival on scene.

3:07 a.m.

Arcata Ambulance's crew, which is stationed at 220 F St., south of Samoa Boulevard, is called out, again through the Cal Fire dispatch. At this same moment, an Arcata Fire crew with two cross-trained emergency medical technicians leaves its station on Janes Road near Mad River Community Hospital.

Elijah Chandler, a friend of Lawson's, told the Mad River Union he ran to Lawson's side almost immediately after his friend was stabbed, finding him bleeding and semi-conscious in some bushes under a small tree on the right side of the cul-de-sac. He says he performed CPR on Lawson for about 15 minutes and was insistent that none of the responding officers helped, but that they were instead "only there to make sure that this group of colored people didn't get rowdy and out of control."

Chandler told the Union that as he was fighting to save Lawson's life, two white women stood nearby, saying, "I really hope that nigger dies."

During her testimony Monday, Casey Gleaton, essentially corroborated that statement, saying she was standing next to her friend Lila Ortega, Zoellner's girlfriend, when Ortega said repeatedly, "I hope that guy dies." "I told her if she doesn't shut her mouth I might be the one to smack her," Gleaton testified. Asked if Ortega might have used a racial slur instead of the word "guy," Gleaton said she didn't remember but she may have because "people do weird things when they're very, very upset and she was very, very upset."

3:08 a.m.

About one minute after being called out, Arcata Ambulance is en route to the 1100 block of Spear Avenue. Boileau says it's about 3.3 miles from the station to the scene, and the crew chooses to take U.S. Highway 101 north to Sunset Avenue, Sunset over to Foster Avenue, and then make a right on Alliance Road to Spear Avenue.

3:09 a.m.

Seven minutes after the initial 911 call came in, an Arcata Fire crew arrives on scene. McDonald says when the crew arrived a bystander was there waving it in. One EMT immediately made his or her way to Lawson and, according to Chapman, found two police officers administering CPR. According to McDonald the officers had already readied an automated external defibrillator, a device that automatically diagnoses life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias and delivers an electrical shock designed to stimulate a heartbeat.

Meanwhile, the second EMT readied equipment to care for Lawson, including a bag-valve mask to help deliver oxygen into a dying patients airway. When the second EMT got to Lawson, McDonald says they decided they needed to move his body in order to better care for him and ready him for handoff when the ambulance arrived.

To the Union, Chandler said the EMTs "grabbed his left leg and his left arm and just dragged him out from where he was," later saying that a detective on scene told him they did so because they were afraid to administer CPR where Lawson was laying, with Chandler and another Brothers United member nearby.

McDonald says Chandler's description of the EMTs moving Lawson is accurate but not their reasoning for it. "Seconds count. This is a traumatic event that's immediately life threatening," McDonald said, adding that the EMTs' aim was to get to work on Lawson as quickly as possible and to ready him for transport to the hospital. "It's kind of hard but death is not pretty."After reading Chandler's account in the Union, McDonald said his wife spoke to him about it. "She asked, 'If this was your son under the bushes would you have done anything differently?' I said, 'Hell, no.'"

3:10 a.m.

Whatever the rationale for moving Lawson, just about everybody agrees the sight of his body being dragged from the bushes riles the crowd of onlookers.

"That's accurate," Chapman says. "That was not pretty. It's not gentle and it's hard to see those things — really hard to see those things."

The crowd begins pushing and shoving, according to McDonald and Chapman, with EMTs reporting being bumped as they're performing CPR on Lawson and officers trying to keep the crowd back and give the EMTs space to work.

"His friends weren't helping at all," one neighbor says of the crowd surrounding Lawson. "(The officers) were outnumbered. They didn't have enough cops. They were doing their best."

Another neighbor said additional officers responding to the scene were met with hostilities from the crowd, particularly a group he described as "gang bangers" with that "Oakland mentality."

Meanwhile, EMTs continue doing CPR, according to McDonald. While Chandler alleged to the Union that, at points, EMTs seemed to be doing nothing, McDonald says they were constantly working on Lawson and preparing him for the ambulance's arrival. There are certain things — like using the defibrillator, which requires everyone to be hands-off for 30-40 seconds while it assesses the patient's heartbeat — that may seem odd to onlookers. "To someone from the outside, it might look like we're not doing anything," McDonald said.

As to the notion that his crew may have reacted differently because Lawson and his friends were black, McDonald said he takes any criticism of his personnel seriously but has seen nothing to make him believe race played a factor in how his crew performed that morning.

"I don't want to be cliché about it but our job is to help people," he says. "I would not stand for that in our department. Race, creed, orientation — it doesn't matter. Our job is to help people."

3:15 a.m.

Thirteen minutes after the first 911 call, an ambulance arrives on scene. Boileau says his paramedics arrive about eight minutes after being called out to find that the EMTs have situated Lawson in a place where paramedics can immediately begin assessing his condition and preparing him for transport. "I think they did very well to have the patient in a place where we could work," he says. "That's important."

Boileau says the crew then began moving Lawson toward the ambulance, saying "the thing that saves people who have been stabbed is getting them into surgery, so that's the focus."

But Boileau says there were a lot of people there and a lot of people "trying to help," including by pushing the gurney, all of which complicated efforts. "That can just slow things down," he says.

3:21 a.m.

With Lawson on board, the ambulance departs for Mad River Community Hospital. Boileau says according to the industry standard for a trauma scene, paramedics are doing well if they can get he patient loaded and en route to a hospital within 10 minutes of their arrival on scene. His crew did it in about six. "From my perspective, the timeline of response is actually very good," he says.

An Arcata police officer follows the ambulance, and those remaining work to secure the crime scene.

3:22 a.m.

Lawson arrives at the emergency room and is rushed into surgery. According to Chapman, at the time he arrived at the hospital, Lawson still had a heartbeat and paramedics were maintaining his respiration through CPR.

4:07 a.m.

Lawson is pronounced dead. By this time, a crowd of more than two dozen has gathered outside the hospital and in the emergency waiting room. Many are friends of Lawson's who were at the party — some having simply walked there from the scene.

The crowd grows distraught upon learning of Lawson's death, and the hospital staff sets up a room where it offers grief and counseling services, and hospital employees work to deescalate tensions.

Sitting in the Humboldt State University library last week, Katauri Thompson says he's still working to process everything. He was at the party that night but left as soon as police started arriving, unaware that his friend had been stabbed. But he says he believes what he's heard: that the emergency response wasn't adequate and that police were "more worried about people rioting" than his friend who lay bleeding to death.

For his part, Chapman says he's heard the criticisms of his officers and takes them seriously and — once the murder investigation is complete — will make sure they are thoroughly investigated. "But from the preliminary review of this, I think the officers are being demonized," he says. "From the audio recordings and the video recordings that we have from the police cars and the radio traffic, I heard officers trying their best to get control of the scene and doing what they could to help," he says. "What I've seen in my initial evaluation is that it's a dynamic and chaotic scene and the APD officers that responded, in particular the two officers who were involved in CPR, did everything they could to save Josiah Lawson's life."

Chapman has deemed the case "complicated" and both APD and the university have publicly called for more witnesses to come forward. Emblematic of how shaky the case against Zoellner may be is the fact that his defense team chose to allow his preliminary hearing to go forward on Monday when it had the option of delaying to give its investigators more time to look into the case. Even if prosecutors can prove Zoellner stabbed Lawson, some close to the case feel there's a potentially strong self-defense argument to be made. Meanwhile, some in the community are calling on the district attorney's office to charge Zoellner with a hate crime — which would require prosecutors to not only prove Zoellner intentionally killed Lawson but that race was also a motivating factor in the slaying.

Thompson, who's known Lawson since grade school and in some ways followed him up to Humboldt, says he doesn't know what comes next, whether he'll return to HSU in the fall or go elsewhere. The freshman says that since arriving on campus he's felt he was sold a bill of goods, wondering what happened to the pictures showcasing diversity on the school's website and fliers as he looks out over a predominantly white campus in a predominantly white city in a predominantly white county.

Racial tensions are nothing new to HSU and have recently been the subject of an ongoing series of campus dialogues. But students like Thompson and others feel administrators have done little to take on the issue proactively. Now Lawson's death has brought it to the forefront. "It's like they didn't want to see it but now that somebody's dead we know it's not OK," Thompson says. "Honestly, we don't see anything getting better. We don't."

Thompson leans back and smiles, recalling how he and Lawson used to have this thing, where they'd frequently look at each other and ask simply: "What now?" It's a question they'd pose to each other matter-of-factly after finishing dinner, or plaintively after something bad happened or challengingly after reaching a goal or running into an obstacle.

David Josiah Lawson's death has laid bare something hidden in plain sight. A few days after the killing, Arcata Vice Mayor Sofia Pereira held back tears at a council meeting and proclaimed that "as a community, we failed Josiah. And we failed other students of color who stated over and over again that they do not feel safe or welcome here."

No matter what exactly happened the morning of April 15, it's now more clear than ever that racial tension and distrust are very present in Arcata, as is the constant strain between campus and the wider community. The question is, what now?

Editor's note: This story was updated from a previous version that misspelled Arcata Fire Chief Justin McDonald's name. The Journal regrets the error.

Thadeus Greenson is the news editor at the Journal. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Speaking of...

-

Robert William Astrue: 1928-2023

Feb 13, 2024 -

Susan Ellisa MacConnie: 1952-2023

Oct 1, 2023 -

Voter Guide Contains Error on Arcata City Council Race

May 6, 2022 - More »

more from the author

-

Deputy Shoots Cutten Shooting Suspect

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Officials Weigh in on SCOTUS Case's Local Implications

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Arcata Lowers Earth Flag as Initiative Proponents Promise Appeal

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023