McKinleyopolis: Humboldt County's Largest Unincorporated Area Mulls Whether Cityhood is a Path to Prosperity

By Elaine Weinreb[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Some see McKinleyville — Humboldt County's third-largest population center, and one of its fastest growing — as the 18-year-old high school graduate ready to leave home. The prospect of freedom from parental control is tempting — she'll finally be able to make her own decisions about where she goes and how she'll get there. But she would also face the burden of fully supporting herself, paying the rent and utilities without help from mom and dad, maybe even getting a second job to make ends meet.

Does McKinleyville really want the freedom — and the financial responsibility — of becoming an incorporated city? It's a question that's been raised repeatedly over the past 50 years, as the community has quickly grown from a small agricultural village to what would be Humboldt's third largest city if it were, in fact, a city. The idea made it to the ballot in 1966 but the community, then largely agricultural, saw few advantages to cityhood and voted it down. A few decades later, in 1997, the question was re-considered. A study conducted by students at Humboldt State University examined the revenues and expenses associated with running the town, concluding that McKinleyville generated enough revenue to stand alone, though no one pushed the idea forward.

But now, recently seated Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone has been pushing the issue since upsetting incumbent Ryan Sundberg in last year's election. Madrone says that while on the campaign trail, many McKinleyville residents asked him if incorporation would be possible. He's now asking the same question, wanting to examine the county's finances to see if incorporation is still financially feasible.

"Is the county making money on McKinleyville? Is it losing money? Nobody knows," Madrone says. "If (the county's) making money, (McKinleyville) should be getting more services. If it's losing money, (the county) might well want to get out from under the burden of running a city."

In recent weeks, Madrone has gathered support — albeit somewhat reluctant — from the McKinleyville Community Services District's Board of Directors and the McKinleyville Advisory Committee for his fact-finding mission, as both voted to support his request to start having county department heads track how much of their budgets are being spent on providing services to McKinleyville. In the coming weeks, he's slated to take the request back to the board of supervisors in an effort to move the process forward.

Interestingly, for an idea that's now bounced around for more than a half-century, not to mention one that hinges on a lengthy bureaucratic process and deep-dive accounting, the question of whether McKinleyville should step out on its own is divisive in the town where it was long bragged that horses have the right of way. It's so divisive, in fact, that many contacted by the Journal for this story asked not to be identified, whether or not they had much to say.

"I support the idea of getting financial data on McKinleyville expenses and income to the county on which to base decisions about incorporation but I have no opinions on it yet," said one woman, asking that her name not be used in the story.

"This is a really divisive issue," said another, "so I don't want to be quoted about it."

Humboldt County is home to seven incorporated cities — Arcata, Blue Lake, Eureka, Ferndale, Fortuna, Rio Dell and Trinidad. Each is governed by an elected city council, whose members listen to their constituents (or are supposed to, anyway) and then negotiate with each other to make decisions and plan for their city's present and future needs. They have control over some — but not all — of the revenues collected through property taxes, sales taxes and vehicle license fees.

A city council must also make sure basic services are provided to the town's residents and there is enough money in the budget to pay for them. Such services include law enforcement, road maintenance, delivery of drinking water, processing of wastewater, trash collection, maintenance of parks and trails and whatever other amenities citizens decide they are willing to pay for.

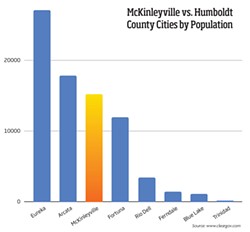

McKinleyville does not have a city council. Its major decisions are made by the county Board of Supervisors, with one of its five members representing the county's expansive Fifth District, which includes McKinleyville and stretches from the Mad River north to the county line and east past Willow Creek. In the frequently polarized district, McKinleyville voters not only must grapple with the likelihood they disagree with their supervisor on a given issue, but that said supervisor is also juggling the interests of many smaller communities scattered over hundreds of square miles. For a town with more than 15,000 residents — or more than double the combined populations of Rio Dell, Ferndale, Blue Lake and Trinidad — McKinleyville residents can sometimes feel they don't have a seat at the table.

McKinleyville takes care of most of its own basic services — water, sewage, parks and recreation and street lights — through its community services district, which collects monthly fees according to the amount of services provided, and most people seem reasonably contented with it. However, community planning, zoning decisions, road maintenance and law enforcement services are all provided by the county and McKinleyville residents have no direct voice as to how much the county will spend on these services, and how, where and when they will be delivered.

Some residents wish they had more direct control over planning their community's future and would like to see the town incorporate. Others are perfectly content with things staying the same, not wanting to take on the added tax burdens and responsibilities that would likely come with cityhood.

The basic problem with incorporation is financial. Even after the community incorporates, state law requires that some of the city's property, sales and vehicle tax subventions go back to the county. Current state law demands any new incorporations be revenue neutral, meaning they won't negatively impact the counties from which the fledgling cities are splitting. Ideally, the savings from the counties' no longer providing services to the city would compensate for the loss of tax revenue the counties would face. But that one-for-one trade-off seldom happens. If a county does lose money through the transaction, the city would have to find some way of paying it back, which generally translates to new taxes in the new city. And even if the county does not lose money, the new city has to fund the services previously paid for by the county.

But there's more to such a move than finances. After all, how many 18 year olds would ever leave home if analyzing the move strictly on a dollars-and-cents basis?

When you listen to those who favor incorporation in McKinleyville, you quickly get the sense their frustrations and curiosities extend beyond a balanced budget. Instead, it's often the stuff of the high school senior tired of the way his or her folks stock the fridge, decorate the home, set curfews and dole out punishments. Some simply feel their voice doesn't carry much weight around the proverbial family dinner table.

There was the recent controversy surrounding the permitting of a Dollar General store at the corner of McKinleyville Avenue and Murray Road, right across the street from McKinleyville High School. Many residents felt it was an inappropriate locale for the discount store, which now sits in a predominantly residential neighborhood, but the county had zoned the property such that the store was a principally permitted use. By the time Dollar General came knocking, its hands were tied. If McKinleyville were an incorporated city, it could make its own zoning maps but, at present, the county is the boss on land use matters.

There are plenty of other examples, too. There was the flap over the county's decision to build a social services center in town and the zoning provision that made it difficult — and costly — to open pre-school childcare facilities in McKinleyville, despite a desperate need.

Others point to 2010, when the county decided that in order to meet state-defined housing goals, it would zone swaths of McKinleyville for high-density, multi-family housing developments, despite the community services district's protestations that it didn't have the sewer capacity to accommodate such development. The district sued and, eventually, the county backed off.

But the county nonetheless passed a General Plan Update that many felt ignored or trampled the existing McKinleyville Community Plan on which many residents had labored long and hard. (Some also complain that the county hasn't done enough to support the McKinleyville Town Center plan, though others deem that more of a failure of private developers to get the ball rolling.)

Then there was the financial crisis of 2011, when amid slashing budget cuts then-Sheriff Mike Downey threatened that he would have to close the McKinleyville substation. Downey ultimately relented, though the budget essentially left just two deputies to respond to calls in the entire Fifth District.

It was amid this backdrop of frustration — potentially exacerbated by McKinleyville's seeing an 11.6 percent population spike that nearly doubled the countywide growth rate from 2000 to 2010 — that spurred then-Fifth District Supervisor Sundberg in 2012 to come up with compromise of sorts. Sundberg pushed forward the idea of a planning committee made up of seven appointed McKinleyville residents, property owners or business owners who could gather input from their neighbors and advise the county on McKinleyville's concerns. Given the catchy nickname The McMAC, the McKinleyville Municipal Advisory Committee was designed to give the town a larger seat at the county's table, if strictly in an advisory capacity.

The McMAC is responsible for reviewing and commenting on proposed zoning amendments, land use amendments and long-term planning issues that affect McKinleyville. It can also comment on public works, health, safety, welfare and public financing, though it is limited to big-picture decisions and is barred from weighing in on property-specific matters, like conditional use permits.

Members are appointed by the county Board of Supervisors, with the majority being appointed by the sitting Fifth District supervisor. The committee is tasked with working closely with the county's planning and public works departments, as well as the clerk of the board of supervisors. Meetings are agendized, open to the public and the committee has to follow all state government transparency laws.

Formed in 2012, the McMAC has since maintained a low profile. A sample of minutes downloaded from the county website shows the committee keeps busy, interacting with a variety of other public agencies, including the sheriff's office, the public works department, the Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District and the county planning department. Occasionally, it has rallied the public, such as in support of Measure Z. But its role remains advisory and it has no authority to enact the will of the people it represents.

Its members also aren't elected but appointed, meaning its makeup is subject to the whims of the sitting Fifth District supervisor and the balance of the board. One McKinleyville resident told the Journal the makeup of the committee has been heavily slanted toward business owners in the past — calling it a "chamber of commerce spin-off" or the "McK-Rotary" — but others said it has done a solid job of making the community's interests known. Several lamented that as an advisory body, it just doesn't have the clout to garner public involvement and keep residents informed and contributing.

One resident said it's "tough" to think that more than seven years after it was launched as a way to bring their voices to the county's decision makers, most McKinleyville residents don't know much about the McMAC or what it does.

Madrone, who took office in January, has wasted little time pushing for more information on what incorporation would mean for McKinleyville and the rest of the county. At the board's Feb. 19 meeting, he asked his fellow supervisors to consider directing county department heads to track costs that originated in McKinleyville for a 12-month period, after which they'd report their findings back to the board.

The idea, he explained, was to get a picture of how much money the county was spending to provide services to the town.

At first, the board seemed dubious. Fourth District Supervisor Virginia Bass commented that "annexation" was "a really bad option for cities." Second District Supervisor Estelle Fennell said she was concerned about the costs to the county's department heads in taking on extra work that had not been included in the county's annual budget.

Some supervisors wanted to see some evidence of community buy-in for the idea of exploring incorporation. Madrone promised to go back to the MCSD board and the McMAC seeking resolutions officially asking the supervisors to pursue the information-gathering mission.

County Administrative Officer Amy Nielsen suggested a compromise. Instead of asking department heads to begin tracking the information, the board could "direct the CAO to work with all county departments to determine what efforts it would take to come up with cost estimates for McKinleyville." Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson turned this into a motion, Bass seconded it and it passed unanimously.

Madrone later consulted the Humboldt Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO), which is tasked with sorting out issues that involve more than one entity, kind of like a family law court for relationships between cities, counties and special districts.

The LAFCO Board of Directors is composed of city and county officials, including Fennell, Wilson and Arcata City Councilmember Paul Pitino. George Williamson, who owns the consulting company Planwest Partners, serves as the commission's senior advisor.

LAFCO staff prepared a four-page handout that outlines the detailed procedures involved when a town looks to incorporate. First, the applicant must produce a preliminary study that deals with costs, revenues and how various services would be provided to the new community. This is generally performed by a professional consultant at a cost of about $50,000. Then either a local agency — like the community services district or the McMAC — passes a resolution asking for incorporation, or proponents circulate a petition among the citizenry, requiring 25 percent or more of the registered voters in the community to sign on.

After one of those steps is completed, LAFCO would then do its own financial and legal review of the issues involved, confirm the proposed boundaries of the new community and conduct an environmental review. All these costs would be passed on to the applicant.

During this process, if 50 percent of McKinleyville voters were to protest for any reason, presumably via a petition, everything would come to a halt and the issue would be dropped. But if that doesn't happen, and if LAFCO were to approve the proposed incorporation, one final election would be held. If the majority of registered voters in McKinleyville were to approve, the new city would be incorporated.

Madrone reasoned that there is no point in spending the money on a feasibility study without first getting an estimate of what it costs the county to keep McKinleyville running. But first he needed to do his homework and show his fellow supervisors that McKinleyville residents think incorporation is an idea that warrants exploring.

On April 3, Madrone addressed the MCSD Board of Directors — the only elected board representing all the town's residents — and asked it to pass a resolution asking the supervisors to pass a resolution formally directing the sheriff's office and county public works department to begin tracking expenses in McKinleyville. Data about revenues, Madrone pointed out, was already readily available through the tax collector's office, but gathering information about expenses would take more effort.

This was not an easy sell. Most of the directors admitted that getting information was a good thing but said they were not sure about the end result or motive. Director Dennis Mayo was skeptical about the whole process.

"You can get information that doesn't tell you anything," he said. "Because one year, the county expenditures can be radically different in an area than another year in an area. ... I've never had anybody ask me, 'Why don't we incorporate?' Not ever. ... We're a very good, well-run district. I don't see any city run better."

He later added, "I don't want to be paying parking tickets down at the shopping center to pay for the meter maid."

Director Mary Burke, on the other hand, thought getting more financial information would be helpful.

"I'm looking for information that would help us be able to make decisions," she said. "I cannot say whether our community would move forward with wanting to vote on incorporation. "

Director David Couch said the district has lots of options and could opt to provide many of the services the county currently provides, even without incorporating.

"As a special district, we could have our own police department," he said. "We could have our own planning department as a special district. But we'd have to pay for it. But I'm not going to advocate for it because we don't have the revenue stream. ... I'd be happy to get more information."

Eventually, the board narrowly passed a resolution, supported by Burke, Corbett, and Couch, asking the board of supervisors to direct county staff to track county expenses within the MCSD's boundaries. Mayo and Director Shel Barsanti opposed the move.

On May 22, Madrone went to the McMAC to ask for its support getting the county to cooperate with his fact-finding efforts.

Madrone said communities like direct control over their planning, noting that McKinleyville created its own community plan in 2003 but, when the county changed the General Plan, it changed the provisions of the community plan without notifying the residents.

"The goal of this is to gather current financial information on revenues and expenses within the MCSD boundary area," Madrone said. "The last time this information was collected was 20 years ago and they were not able to get detailed expense information because it's never been tracked that way. ... Once we have that information, my goal is to hold a community forum where we can discuss that information.

"This is the most logical way to start," Madrone continued. "Rather than spending $50-grand on a consultant, I'm being a fiscal conservative, saying can we get this information in a simpler way without costing the community anything by working with department heads to do something that doesn't take a lot of time and effort."

While the committee's members generally agreed that collecting information would be a good thing, the McMAC's conversation indicated some skepticism.

"Arcata and McKinleyville have approximately the same population," said MCSD General Manager and McMAC member Greg Orsini. "But the MCSD's budget is about $8 million and Arcata's is $40 million. We would need some kind of city sales tax. Nearly every other city has one."

Madrone countered that people don't mind paying a tax if they see a direct benefit. "Look at Measure Z and Measure O," he said, referring to recently passed sales tax initiatives.

Several committee members wondered how useful collecting information over a one-year period might be, considering conditions constantly change. McMAC member Kevin Jenkins noted that the McKinleyville Chamber of Commerce had previously tried to investigate incorporation but was stymied by the lack of financial information.

After about a half-hour of discussion, committee member Burke, who also serves on the MCSD board, moved that the McMAC support Madrone's requests. The motion passed unanimously.

With two resolutions of support under his belt, Madrone can now return to the board of supervisors and once again ask for it to direct county staff to begin tracking McKinleyville's financial information. While most in McKinleyville won't say exactly where they stand on the incorporation question — or at least not publicly — most agree, if somewhat reluctantly, that it can't hurt to look at the numbers.

"I'm in support of finding out the estimated profit and loss numbers for McKinleyville, and then assessing the situation from there," said Katie Cutshall of Azalea Realty. "The numbers will tell us if it makes sense to incorporate or not."

Speaking of...

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

Trouble on the Mountain

A popular outdoor recreation area is also a makeshift shooting range, causing growing safety concerns

- Jan 11, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023