Crash

Humboldt has one of the highest vehicle fatality rates in the country. Is it the roads or us?

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It was Aug. 25, shortly before noon, and Jason Dewayne Fleming, 41, was driving along Lower Pacific Drive, not far from his Shelter Cove home. For reasons that are still under investigation, Fleming lost control of the car and crashed through a wooden fence before careening down a steep bluff, coming to rest about 20 feet down. Fleming, who police suspect had been drinking, was killed on impact.

About six weeks earlier, on July 8, two U.S. Forest Service firefighters, Dale Alexander Mendes and Jason Fritz Price, left work in Salyer. The following morning, a passerby found Mendes' Toyota SUV overturned in the Trinity River near Kimtu Beach, apparently having veered off Seeley McIntosh Road and into the water sometime during the night. Mendes, 29, and Price, 20, were both dead inside. A toxicology report later found both men had been drinking, with Mendes recording a blood alcohol level of .21 — more than twice the legal limit. He also tested positive for a prescription sedative.

Six days before Mendes and Price got in that SUV, 23-year-old Daniel Jeffrey Pudlicki was pronounced dead at Redding's Mercy Hospital. About a month earlier, on a warm Arcata evening, he'd been crossing Samoa Boulevard near I Street with a friend when he was struck by a black and silver Toyota pickup that fled the scene. The driver of that truck, Donald David Watts, was later arrested and charged with vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated. He has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.

Twelve days before Pudlicki's death, at about 5 p.m. on June 20, a 2007 Nissan Altima travelling south on U.S. Highway 101 near Myers Flat crashed into a dirt embankment and flipped several times. A passenger in the car — 32-year-old Stephanie Marie Vandelinder — wasn't wearing a seatbelt and died at the scene.

At about 1:30 a.m. the day before, 31-year old Bridgette Bailey was alone in her 1996 Ford sedan, speeding northbound on U.S. Highway 101 in the safety corridor, going between 80 and 100 mph. According to records from the Humboldt County Coroner's Office, she was legally drunk and high on methamphetamine when she crossed over the median and rolled across both southbound lanes before coming to rest on the railroad tracks. Bailey wasn't wearing a seatbelt and was ejected from the vehicle. She died on impact.

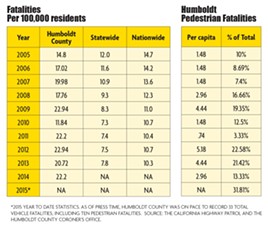

And so goes the steady drumbeat of vehicle fatalities in Humboldt County, which plays on with alarming — if numbing — consistency, leaving a trail of lives both shattered and lost. Statistics show Humboldt has some of the most dangerous roads in the country, with fatal accident rates double the national average and nearly triple those of California. The rates are so high, in fact, that in 2013 Humboldt's per-capita motor vehicle fatality rate — 20.72 deaths per 100,000 residents — eclipsed that of any state in the country save for Montana (22.6), according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

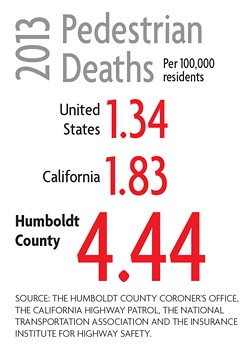

Our rates of vehicle-versus-pedestrian fatalities are also some of the highest in the country. In 2013, the last year for which data is available, California recorded 1.83 pedestrian fatalities per 100,000 residents. Nationally, the rate was 1.34. In Humboldt that year, it was 4.44.

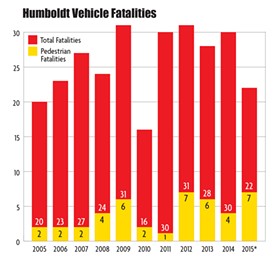

Perhaps worst of all, Humboldt County's rates in both categories have trended sharply upward over the last decade, while national and state rates have dropped almost 50 percent. Humboldt is on pace to have one of its deadliest years yet. About two-thirds of the way through 2015, the county has already recorded 22 vehicle-related deaths, seven of which were pedestrians. If that rate continues, we'll close the year with 33 vehicle-related deaths, including 10 pedestrians — 10-year highs in both categories.

So what makes Humboldt's roads so deadly?

Stewart seems to be spot on. According to data from the coroner's office compiled by the Journal, drugs and/or alcohol have been a factor in 19 of the 22 roadway fatalities so far this year, and half of those recorded last year. Differences in testing patterns, data collection and record keeping make it difficult to determine the extent to which they were involved in prior fatalities.

Looking at this year's statistics alone, there's a clear correlation between methamphetamine and alcohol use and traffic fatalities. Of the 22 people killed on Humboldt roads so far in 2015, seven — including three pedestrians — had methamphetamine in their systems, according to the coroner's office. Ten — including two pedestrians — had blood-alcohol levels above the legal limit for driving. Prescription drugs also were also present in some, like a wheelchair-bound Rio Dell man who tested positive for a heavy dose of morphine after he wheeled into traffic on a freeway off ramp and was struck and killed in June.

Local California Highway Patrol spokesperson Matthew Harvey agreed drugs and alcohol are prime factors, pointing out that his agency has responded to three double-fatality accidents this year and all were DUI related. However, Harvey said Humboldt's traffic safety issues run deeper than DUIs and are likely the result of a complex fabric of factors.

"There are so many layers to look at," he said. Harvey said Humboldt is vast and rural, meaning the average resident probably logs more vehicle miles per year than a counterpart in a more urban area. We also have a lot of transients and visitors, he said, noting that they aren't familiar with our rural roads and generally comprise a portion of our grisly crashes. Compounding that out-of-towner factor, Harvey said, is that Humboldt's roads can be unforgivingly narrow and windy. And because Humboldt is so rural — with roads stretched across 4,000 square miles of land — emergency responses can take a while, meaning some crash victims die on scene before medical personnel arrive.

But — next to drug and alcohol related crashes — Harvey said by far the biggest problem on Humboldt's roads is a stubborn, almost cultural refusal to wear seatbelts. "We see less seatbelt compliance in rural areas than we do in the city," Harvey said. "It's hard to know why that is, but people don't feel like they need to put their seatbelts on." Harvey pointed to a quadruple fatality accident that occurred on State Route 36 last August as an example. In that, the deadliest crash in Humboldt County in more than a decade, a 2002 Dodge Dakota pickup truck carrying eight people veered off the road and collided with a tree, killing the driver and three unrestrained passengers, including a 13-year-old girl who had been riding in the truck bed. A toxicology test on the driver later came back positive for methamphetamine.

In addition to the cultural aspect of refusing to click it, Harvey said that, unfortunately, the drug and alcohol problems seem to exacerbate the seatbelt problem, noting that drivers under the influence are less likely to belt up and make sure their passengers do the same.

While Humboldt's traffic safety problems stretch from Mendocino to Del Norte, and from the Pacific to Trinity, there's no question their epicenter lies in Eureka. According to the California Office of Traffic Safety, Eureka was the most dangerous of more than 90 similar-size cities for fatal and injury traffic collisions in 2010, 2011 and 2012, the last three years for which the rankings are available. Similarly, the city has ranked in the bottom three for pedestrian safety from 2008 through 2012. Eureka Police Sgt. Gary Whitmer knows the intricacies of the problem better than probably anyone in town, having worked traffic for 13 of his 20 years on the force. "It's always been bad," Whitmer said with a sigh before being asked why. "I've been asked that question a lot of times over the years and if I had the answer, we'd be able to do something about it. But I don't. It's really not one specific thing."

Whitmer said having the biggest regional freeway running directly through Eureka's downtown and it being the county seat — meaning its population of 27,000 probably doubles during the day — certainly contribute. But Whitmer said there's also something less tangible at play.

Almost a decade ago, Kim Bergel, now a Eureka city councilmember, was the mother of a couple of young kids and spent gobs of her time out on city streets, pushing a stroller or riding her bike, toting her kids behind her in a tag-along trailer. "I just felt so unsafe," Bergel said. "I just felt like cars didn't pay any attention." Not one to sit idle, Bergel said she joined Eureka's Transportation Safety Commission with the hope of making a difference.

The commission has made attempts at public outreach in recent years and tried to identify the most dangerous intersections in town. The results aren't surprising, as surveys found residents felt the Broadway corridor, Fourth and Fifth streets were littered with dangerous intersections. They also zeroed in on H and I streets, especially where they intersect with Sixth and Seventh streets. Recently, the city has taken a number of steps aimed at improving traffic safety, including reducing speed limits in some areas, adjusting traffic signal timing for smoother transitions, installing radar speed detecting signs in problem areas and upsizing the face of traffic lights from 8 to 10 inches in diameter to a foot.

Most notably, with the help of a grant from the California Office of Traffic Safety, the city launched a massive pedestrian safety public awareness campaign, dubbed "Heads Up," encouraging residents to disconnect from distractions, use crosswalks and remain visible. Whitmer said the pedestrian education effort is huge, as he said pedestrians and bicyclists are at fault for a shocking number of accidents in town.

"We have a lot of people that just blatantly walk out into traffic, and it's everyone: the transient population, business people, students," he said. "That flashing red hand — we call it the 'red hand of death' — people walk against it. There's this misconception that pedestrians always have the right of way, and they don't."

In addition to current efforts to improve engineering in the city and raise public awareness, Whitmer said he thinks increased enforcement might help. EPD currently only has two traffic enforcement officers, and they are sometimes pulled to do patrols and other department functions when staffing is short. If there were a large, sustained traffic enforcement effort, Whitmer is hopeful it would yield positive results, noting that when people see a cop on the side of the road they tend to slow down and pay more attention.

Back at CHP, Harvey had a similar take, noting that his department has had some staffing shortages recently that have kept it from patrolling as much as it would like, especially in outlying areas. This year, Harvey said his department is ramping up staffing and will hopefully have a maximum presence on the streets. Traffic enforcement patrols, Harvey said, have a strong impact. "You pull one person over for speeding and every other person that passes you on the roadway gets that message," he said.

But additional enforcement is no magic bullet. Whitmer said EPD has been fortunate over the years to get a lot of Office of Traffic Safety grants, which pay officers to work overtime shifts spent entirely targeting traffic violations. A few years back, Whitmer said the department also got a Safe Streets grant, which funded regular CHP traffic enforcement patrols throughout the city. "The weird thing was that was one of the top years for the highest number of collisions in the city," Whitmer said. "And CHP did a great job. They came in and wrote all kinds of tickets, and you'd think that would make a big difference and slow people down."

Despite a raised awareness of the problem and numerous efforts to address it, Humboldt roads are on track for their deadliest year in recent memory, on pace to record 33 fatalities, including an unprecedented 10 pedestrians. Harvey and Stewart at the coroner's office believe these numbers are a symptom of a larger drug and alcohol problem. That makes the issue harder to address, akin to trying to mitigate the impacts of local homeless populations without addressing the root causes of homelessness in the community.

Harvey said it's imperative for Humboldt residents to be proactively aware of the problem, so they won't get in the car with someone who's been drinking or will speak up when they're at a bar or a dinner party and a friend who's had too much to drink tries to get behind the wheel. One thing people need to understand, Harvey said, is that there's little margin for error in Humboldt County.

"When you're on a major freeway, they're typically straighter with guard rails, medians and shoulders," he said, adding that a motorist can get distracted, leave the roadway and often live to tell about it. That's not the case with many roads in Humboldt, like State Route 36, which twists and turns along the banks of the Van Duzen River. "Any local knows that roadway and why it's dangerous," Harvey said, adding that more than 35 percent of the fatalities CHP responded to last year were along State Route 36.

Sure, Whitmer concedes, Humboldt has some windy roads and tricky intersections. But he's not willing to point the finger at them for the county's ranking as one of the deadliest places to drive in the country. "I don't want to say the roads are dangerous," he said, pausing for a moment. "But I think some of the people driving them are."

For a deeper look at Humboldt's drug and alcohol problems, and efforts to address them, pick up next week's Journal, on newsstands Sept. 10.

Data:

Fatalities:

(Year — Total Fatalities — Fatalities per 100,000 residents — Pedestrian Fatalities — PF Per capita — PF/Total — statewide fatalities per 100,000 residents — nationwide fatalities per 100,000 residents)

2005 — 20 — 14.8 — 2 — 1.48 — 10% — 12.0 — 14.7

2006 — 23 — 17.02 — 2 — 1.48 — 8.69% — 11.6 — 14.2

2007 — 27 — 19.98 — 2 — 1.48 — 7.4% — 10.9 — 13.6

2008 — 24 — 17.76 — 4 — 2.96 — 16.66% — 9.3 — 12.3

2009 — 31 — 22.94 — 6 — 4.44 — 19.35% — 8.3 — 11.0

2010 — 16 — 11.84 — 2 — 1.48 — 12.5% — 7.3 — 10.7

2011 — 30 — 22.2 — 1 — .74 — 3.33% — 7.4 — 10.4

2012 — 31 — 22.94 — 7 — 5.18 — 22.58% — 7.5 — 10.7

2013 — 28 — 20.72 — 6 — 4.44 — 21.42% — 7.8 — 10.3

2014 — 30 — 22.2 — 4 — 2.96 — 13.33% — NA — NA

*2015 — 22 — NA — 7 — NA — 31.81% — NA — NA

* = Year to Date statistics. As of press time, Humboldt County was on pace to record 33 total vehicle fatalities, including 10 pedestrian fatalities.

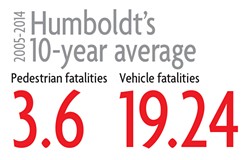

Humboldt’s 10-year average (2005-2014):

19.24 vehicle fatalities

3.6 pedestrian fatalities

2015:

22 — Total traffic-related fatalities

19 — Times the person killed tested positive for drugs or alcohol

7 — Pedestrians killed by vehicles

5 — Killed pedestrians who were legally drunk or on methamphetamine

10 — Times the deceased was above the legal blood-alcohol limit

7 — Times the deceased tested positive for methamphetamine

3 — Times the deceased tested positive for prescription narcotics

Pedestrian deaths per 100,000 residents in 2013:

California — 1.83

United States — 1.34

Humboldt County — 4.44

Where We Rank:

The California Office of Traffic Safety ranks counties and cities annually on per-capita accident rates. Humboldt County is ranked against all of the state’s 58 counties, while Eureka is compared with 92 similar-sized cities. The rankings go from worst to best, so a first-place finishes means more accidents per-capita than anywhere else. Here’s where we stood in 2012, the last year for which statistics are available.

Eureka

Total fatal and injury collisions — 1

DUI crashes — 4

Pedestrians hit — 2

Bicycles hit — 5

Hit and run collisions —5

Composite ranking — 6

Humboldt County

Total fatal and injury collisions — 13

DUI crashes — 4

Pedestrians hit — 2

Bicycles hit — 8

Hit and run collisions — 3

Composite ranking — NA

Source: The Humboldt County Coroner’s Office, the California Highway Patrol, the National Transportation Association and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

more from the author

-

Deputy Shoots Cutten Shooting Suspect

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Officials Weigh in on SCOTUS Case's Local Implications

- Apr 25, 2024

-

Arcata Lowers Earth Flag as Initiative Proponents Promise Appeal

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023