Can Humboldt County Solve Addiction?

Where our resources lift addicts up, and where they let them down

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Editor's Note: This is the second in a two-part series looking at addiction on the North Coast. The first installment ("What's Killing Us?" Sept. 10) analyzed the theories of addiction and its causes.

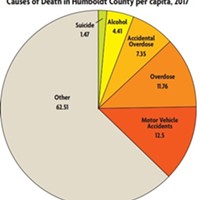

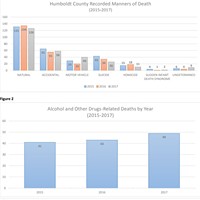

The first thing you see when you walk into detox are the names of the dead. A wooden plaque on the wall displays them on brass plates, a tribute to former patients of Alcohol and Drug Care Services in Eureka who did not survive the disease of addiction. Twenty percent of all deaths in Humboldt County over the last three years were related to alcohol and other drugs. Less tangible, and less measurable, are the numbers of those who have broken free from addiction's grasp. What does it take to beat addiction? And what help does Humboldt County have to offer?

"We have many resources," says Dr. Ruby Bayan, Medical Consultant for Alcohol Drug Care Services. "The problem is coordination of care."

ADCS is one of the few programs in Humboldt County that tries to address the multi-faceted challenges of addiction, from health issues to social support to housing insecurity. Although we have six residential and seven outpatient treatment programs, a handful of self-help groups and clean and sober housing options, navigating the requirements of each can be a challenge for both addicts and those trying to help them.

Treatment professionals often stress the importance of willingness. As the adage goes, the first step is admitting that you have a problem. But even the willing may face significant hurdles in their attempts to recover. The first? Staying clean long enough to get treatment.

It may seem counterintuitive, but most drug and alcohol programs require patients to test clean in order to remain in treatment. This means that patients must be fully detoxed and medically stable before they begin therapy. Marijuana, which can take up to 30 days to leave a person's system, is usually an exception.

But becoming medically stable enough to benefit from treatment is a challenging process. It requires going through withdrawal — experiencing the symptoms that occur when an addict stops using a drug upon which his or her body is chemically dependent. Withdrawal's symptoms are mental, emotional and physical, ranging in intensity from strong cravings to hallucinations to strokes. Hospitalization and medication are sometimes necessary. A person withdrawing from alcohol may receive benzodiazepines; an opiate addict thorazine. Northern Humboldt's lone detox facility — run through ADCS — uses social support such as groups and counseling to help users through the first week of intense craving, but relies on local hospitals to treat and medicate symptoms first.

The program is currently in the process of hiring Bayan as a medical director to supervise and prescribe medications at the nine-bed facility. Executive Director John McManus says that, although hospital staff do their best, they're not addiction professionals, and addicts are often released from care with an inadequate amount of medication, reducing their chance of success. Bayan adds that mental illness, which is a common co-occurring disorder with addiction, has traditionally been treated separately. The appointment of Bayan, who is a child and adult addiction psychiatrist, may go a long way toward creating an integrated approach. But the program is not accessible to all addicts.

The county currently subsidizes beds in the ADCS detox facility for opiate and alcohol addicts because of the medically precarious nature of withdrawal from these substances, but doesn't do the same for methamphetamine users. Methamphetamine withdrawal is protracted and often requires social support but not medication. With only nine beds total in the detox facility, McManus says the county chose to "spend those resources on people who were in jeopardy."

"Folks detoxing from meth can still come in; they should come in," he says. "The main thing they need is a safe place to sleep."

The out-of-pocket cost for a stay at detox is around $125 a day, or addicts with private insurance or sufficient resources can go to Singing Trees Rehabilitation in Southern Humboldt, which charges $3,500 for a week of detox.

Once an addict is stable, he or she can begin treatment, which usually consists of group therapy sessions, individual counseling and attending 12-step groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. But focusing on recovery can be difficult for those whose active addictions included compounding issues such as housing insecurity, legal troubles, mental illness and family dysfunction.

The only free residential programs in Humboldt are faith-based, relying on a "Biblical" understanding of recovery. The county subsidizes a limited number of beds in the two other residential programs, ADCS and Humboldt Recovery Center, for indigent clients, but the waiting lists are long. HRC says that clients can often wait four to five months. These programs accept patients on Supplemental Security Income (SSI). But getting SSI can also be a long process, during which the window of willingness may well close. Patients who don't qualify for SSI must pay between $1,800 and $2,200 a month for residential treatment.

Few insurance plans cover residential treatment. No local residential programs accept MediCal, although county outpatient alcohol and drug services do. Outpatient clients must find their own housing, however. There are several "clean and sober" houses throughout Humboldt, offering dormitory accommodation for anywhere from $250 to $500 a month, but few are structured to accommodate families. Relapsing — getting drunk or high — usually means getting kicked out and starting the process all over again.

Recovery from addiction is more complicated than overcoming the cravings and physical symptoms of withdrawal. It can take months, even years, for a brain whose dopamine levels have been depleted by drug abuse to reach chemical equilibrium. Dopamine is the "feel happy" chemical in the brain that scientists believe addiction hijacks. Most treatment programs top out at between 30 and 90 days, which many professionals feel is an insufficient amount of time to correct the physiological impact of addiction.

"By shortening the amount of time in treatment, dopamine isn't given enough time to reproduce," says Dale Ward, who coordinates alcohol and drug services at Eureka Community Health. Ward uses an opiate addict as an example. Opiate withdrawal (from heroin or prescription drugs) is notoriously difficult, with a host of physical and emotional symptoms. "If he was to go to a three- to five-day detox, then a 90-day program, he might be able to sleep at 45 days. By 60 days, he might be able to have regular bowel movements. But it's going to be awhile before he has the ability to listen."

Even if a longer treatment program is available, many patients will resist taking the necessary time to recover. Some may be mothers who want to return to their children, employees who want to get back to work, or people who just want to return to some semblance of a normal life, one that doesn't revolve around group therapy and restricted residential living. A key point that most counselors try to instill in patients is that however they choose to live their lives once they leave treatment, complete sobriety from all mind-altering substances must be prioritized.

Now a substance abuse specialist at Humboldt Recovery Center, John Remen started his career from a place of hard-won experience. Sixteen years ago he graduated from the program where he now works, after a lengthy run with alcohol and methamphetamines. Remen worked as carpenter for many years, spending most of his money on alcohol and drugs, and much time behind bars. He was 43, sleeping in his truck in a bar's parking lot off Broadway Street in Eureka when he got sober. He had 31 felony arrests on his record.

"My biggest problem is I didn't think I was OK," says Remen. His counselor at HRC was patient with him, coaching him toward a kinder view of himself.

Now a counselor himself, Remen says he knows he's the exception, not the rule.

"A lot of people don't make it. But we get to keep the doors open," he says. "I've had people come through treatment seven or eight times. Then all of a sudden you hear something come out of their mouth and you do a double take, and you know they've got it."

As with most local treatment programs, Humboldt Recovery Center requires its clients to remain abstinent from all mind-altering substances to stay in treatment. Remen confesses that he often regrets having to eject patients who have relapsed, knowing their exit may result in a return to the streets, jail or even death.

Over at ADCS, social worker Tina Garsen says she shares Remen's fears, but keeping a person who is actively using in the same program as addicts trying to get clean is "unfair, unsafe and unkind."

"It sounds harsh, but you have to protect the people who are there to stay clean," she says.

Remen says he tries to pass on to his clients what has worked for him for 16 years.

"I believe in total abstinence," he says.

"Abstinence only is unrealistic for many people," says Brandie Wilson as she crouches to pick up a cigarette butt. We are walking through Cooper Gulch Park, where Wilson and other members of the Humboldt Area Center for Harm Reduction regularly pick up trash, dispose of used needles and distribute information and safe injection supplies to heroin users who might be sleeping and shooting up in the bushes.

The concept of harm reduction has been practiced in one form or another for many years, most notably in the 1980s when activists and public health officials tried to stem the spread of AIDS by distributing clean needles to intravenous drug users. Its primary goal is to reduce the negative health effects of drug use and help addicts take steps toward a healthier lifestyle. Under harm reduction, success can take many forms: an alcoholic no longer at risk of dying from exposure, a heroin addict who enrolls in a methadone program, a methamphetamine user who switches to marijuana. But traditionally, harm reduction is not introduced as a mode of treatment, and old-school recovery advocates are often skeptical of its efficacy. Complete abstinence is easy to measure. Harm reduction is less tangible.

"It's unfortunate. Propaganda will tell an addict that [complete abstinence] is the only way to save his life," says Wilson.

Ward, who is in charge of the Suboxone program at the Open Door Clinic, agrees with Wilson to a point. Suboxone prevents the symptoms of opiate withdrawal and blocks the euphoria of use. Essentially, patients treated with Suboxone get neither high nor get low for as long as they're on it. Ward's patients take Suboxone in concordance with counseling and groups. Nationally, Suboxone has a 40 to 60 percent success rate, measured by the length users stay in the program.

"Total abstinence is available for a select few," says Ward. "I have it. How many people get it? Not many. Building a system around abstinence only is building a system to fail."

Ward says Suboxone is a much better alternative to traditional methadone programs, which prolonged the withdrawal process of users. Like many in the field, he believes a pharmaceutical answer to addiction is right around the corner. A medication similar to Suboxone for methamphetamine users is currently in clinical trials.

Rates of heroin use in the United States have skyrocketed over the past decade, many believe largely in a response to the availability of prescription opiate-based painkillers. Some opiate users — who may have started on the pills as a way to manage pain after injuries — transition to heroin as a cheaper alternative once their prescriptions run out. Chief Deputy Coroner Ernie Stewart and former Public Health program manager Mike Goldsby both note a spike in heroin use and overdoses locally. Stewart says transition from pharmaceutical abuse is a common factor in overdose deaths, calling heroin use a local "epidemic."

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, there were 107.9 opioid prescriptions for every 100 residents in Humboldt County in 2014. Clients in Eureka Community Health's Suboxone program — 200 strong — range from street addicts and county employees to pregnant women and veterans. The pain they've been suppressing with the opiates, Ward says, is often more than physical. Once they stop using, their feelings come to the surface.

In the meantime, there may be many who aren't ready for treatment of any kind. That's where Wilson and her group come in. HACHR was recently awarded a grant by the Humboldt Area Foundation to help its efforts, but Wilson says she has been on the receiving end of skepticism from people who feel handing out clean needles is encouraging use.

"It doesn't matter how you feel about it," she says. "It's not a moral issue. It's a public health issue."

According to the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services, Humboldt's rates of Hepatitis C, a liver disease often spread by sharing needles, are far above the state average. In 2011, Humboldt ranked fifth in the state for newly reported cases of the disease, at 132.7 per 100,000 people versus the state average of 88.3. (Del Norte has the highest rate in the state, with 215 newly reported cases for every 100,000 people.) One in 26 people in Humboldt County lives with the chronic disease, as opposed to 1 in 118 statewide. Sexual contact and sharing personal items can also transmit the disease. On the day we visit Cooper Gulch, Wilson and her friend Michelle Ellis find no needles, but they do find a used condom sitting next to an old shoe in the bushes.

"Yay!" says Wilson, gingerly putting it in a trash bag. "I double-wash my hands when I finish these clean-ups," she adds.

Occasionally they'll find the first aid kits they distribute to users to help clean infections from injections. They consider this a mark of success.

"All we're trying to do is move the addict to the next least-harmful place," says Wilson. "We try to reframe it as, 'We're reducing your healthcare cost.' The bottom line is, these are people, and for the most part people who have undergone some pretty intense things in their lives."

Different cities and countries have experimented with harm reduction techniques that include providing safe injection sites — so users don't have to shoot up in bathrooms or public parks. Locally, several clinics and other organizations offer needle exchange services. Wilson says that one goal of her organization is to offer a safe space to hold groups that don't have an abstinence-only requirement. Many of the people Wilson hopes to reach are homeless, a population she says is uniquely vulnerable to self-medicating with alcohol and drugs.

"Sometimes living without a home requires substance abuse."

It's mid-morning and the north parking lot of the Bayshore Mall has filled with folding tables and vans. A representative of Friends of the Marsh, a homeless advocacy group, trots from table to table, introducing herself. The group recently changed the date of its free weekly meal to coincide with the service fairs that now take place on the last Friday of the month. Organized by the Eureka Police Department's homeless liaison, Pamlyn Millsap, the fair features representatives from Open Door, St. Vincent DePaul, St. Joseph Hospital and several other organizations. The goal is to connect homeless residents living in the PalCo Marsh with services, especially housing. The city has been trying for more than a year to evict the 100-plus people camping illegally in the area. Citywide, Eureka has an estimated 730 homeless people.

"I've never agreed with the statistics," says Millsap, who has been working with homeless people locally in one capacity or another since 1992. "When I was studying social work, they said 40 percent of homeless people have alcohol and drug issues. I just laughed. I think at least 90 percent have AOD issues. I'm seeing second- and third-generation people with AOD issues. It's just heartwrenching."

Millsap is wearing a thick bulletproof vest with the words Homeless Liaison emblazoned across it, a concession to the dangers of her job. Not everyone believes law enforcement officers are the proper means to address homelessness, but Millsap says police do a fine job. She has seen officers pay for motel rooms for families, give people rides to services and write letters for parents in child custody battles. As we speak, several EPD officers walk into the marsh, ostensibly to tell campers about the services fair. People start to filter in, some pocketing the free granola and water, others stopping to talk to representatives, weighing their options. Two toddlers, twin boys, tag after their father as he gets them balloons at the Humboldt Recovery Center table. One little boy has scrapes all over his face. Both are covered in dirt.

"If I was living out there I'd probably be using something too," says Millsap. "Asking people to step out into a new reality is scary. They don't see housing as a success, they've had housing and they blew out of it. They're scared they're just going to lose it."

Proponents of the housing first model argue that those struggling with addiction cannot properly address it until they're safe, warm and dry. Housing insecurity often becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. Homeless people struggle to find employment because they can't keep themselves or their clothes clean. They can't use emergency shelter or sober housing because they can't meet abstinence requirements. Housing stabilizes their lives, allows them to feel safe and grounded long enough to access available resources, the theory goes. A 2009 study published in the Journal of the American Medicine Association found that a program in Seattle that housed chronically homeless alcoholics saved taxpayers $4 million in its first year — by reducing emergency room visits and incarceration. The program did not require sobriety, but there was a documented decrease in alcohol use and health problems related to alcoholism once clients were housed.

Currently, Eureka is working to move people into transitional housing, but the need seems to far outnumber the availability. A full analysis of available housing is due to be completed by mid-October. In the meantime, a number of methods have been proposed to address the issue of people camping in the marsh and other greenbelt areas. Some argue that the police should forcefully evict each person, while others say that would just push them into other areas of the city. Some say the city should install bathroom facilities and use the marsh as a "sanctuary camp." Affordable Homeless Housing Alternatives, a local "safe, warm and dry," initiative, is promoting a village of tiny houses, but no one has proposed a viable site. The one thing that seems certain is that, as divided as people are on what should be done, something must be done.

"The frustration is building citywide," says Eureka Police Department Chief Andy Mills. "We've been very understanding, but we've got to do something about this mess out here."

He gestures to a cluster of trees, a campsite he and two captains just visited. The officers contacted a young woman there who was "strung out on heroin and had injection sites on her neck."

"I told her, 'You have mountain bikes here and we know you didn't buy them.' This theft has to stop," says Mills. He asks Remen, tabling at the fair, if the woman is eligible for treatment. Remen explains that she would probably have to go to detox first.

As we speak, a man comes up and nudges Remen on the back of the knee. Remen turns, greeting the former client by name.

"Hey, how you doing?" says Remen with his customary gruff bark.

"I'm good man, doing good."

"You living out here?"

"Yeah, I am, you know, just doing my thing."

"Okay, well, it's good to see you."

"Good to see you too, man."

The man looks sideways at the officers as he walks away, back down the trail. Both Remen and Ward say they mourn the passing of Proposition 47, which reduced nonserious and nonviolent property and drug crimes from a felonies to misdemeanors. Fewer addicts are being mandated into care and, Remen says, a lengthy rap sheet can be the thing that pushes someone into recovery. It worked for him.

While police officers may be the first point of contact for many people struggling with homelessness, addiction and mental illness, their presence can alienate those who need the help most. And navigating the tangle of services and requirements can be a challenge for trained social workers, not to mention untrained cops. EPD officers talking with Remen, for example, were unaware that Humboldt Recovery Center was a residential program.

Back at the service fair, a woman expresses interest in spending the night at the Rescue Mission but can't find someone to tell her what time it opens. More former clients of Remen stop by to say hello. One, Steve Tyson, tells Remen that he's doing well, staying clean except for the weed. Tyson and his fiancé Terrie Smith have been living behind the Bayshore Mall, off and on, for almost a year. Terrie tells Remen that she, too, is staying clean, except for the weed, and will celebrate a year's sobriety this month.

The couple has no immediate plans to find housing. Smith underwent a medical procedure that left her weak, and she must make weekly visits to the doctor. They'd like to have jobs, they say. They can't go to the Rescue Mission. They have dogs, and the Rescue Mission doesn't let couples stay in the same room, anyway.

Steven Porter, who once volunteered as a street outreach worker and then worked as a case manager for the county, says housing is a "big picture issue."

"There's so much that everyone's trying to do that it ends up just being a bureaucratic maze," he says. "There's overlapping coverage and gaps in coverage. But how do you keep people alive today? I think it comes down to the core conviction of building relationships."

As an outreach worker, Porter would sometimes deliver meals to people who were completely antisocial, even violent. He remembers one man who would just sit inside his tent and scream obscenities. Porter brought food and set it outside. Eventually the man came out and talked to him. After a year or so, he actually began accessing services.

"My opinion is that in order for us to ever get to a place where we genuinely get to the issues of homelessness we have to build a bridge of trust," he says.

A recent Grand Jury report described "a lack of oversight and coordination" in regards to the issue of homeless service. If homelessness, mental illness and addiction are intimately connected, there seems to be as persistent an issue connecting people with resources as there is agreeing on which resources are best suited to addressing their needs. As Bayan at ADCS said, the "continuum of care" seems to be broken. ADCS recently received donations from St. Joseph Hospital and other organizations to revitalize its Serenity Inn, where low-income clients can stay in dormitory accommodations as they get back on their feet. It now boasts a new jungle gym, improved bathrooms and a resource room.

"We're trying to make it more family friendly," says McManus. The program is first come, first serve.

In the meantime, addiction is still stigmatized, abstinence is still the stick by which we measure success, and more than 1,000 children are growing up homeless in Humboldt County, vulnerable to becoming yet more statistics in the annals of communicable disease, overdoses or vehicular incidents. But the recovered walk among us, too, waiting for the light to come on, and for the now dying to swell their ranks.

Resources:

ADCS Detox

445-3869

Singing Trees

http://singingtreesrecovery.com/

247-3495

Clean and Sober Housing

Name: Mark and Karen Mesa

Phone Number: 442-1104

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Men and Women, Dogs Considered

Name: Steve Little

Phone Number: 616-5773

Location: Fortuna & Rio Dell

Accepts: Men, women, kids

Name: Tim Shelly

Phone Number: 499-1266

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Men, women, children

Name: Connie Burris

Phone Number: 845-6744

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Couples and Families

Name: North Coast Veteran’s Resource Center

Phone Number: 442-4322

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Veterans (men and women)

Name: Serenity Inn

Phone Number: 442-4815

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Men and women, children

Name: Agape House

Phone Number: 444-2084

Location: Eureka

Accepts: Women

Under 18?

Raven Project

http://rcaa.org/division/youth-service-bureau/program/raven-project-street-outreach-program

445-7099

Boys and Girls Club Teen Court

444-0153

DHHS Adolescent Treatment Program

268-2800

Harm Reduction

North Coast Aids Project (Eureka)

599-6318

Open Door Suboxone Program (Eureka)

498-9288

Open Door North Country Clinic (Arcata)

822-2481

Redwood Rural Health Center (Redway)

923-2783

United Indian Health Services (Weitchpec)

(530) 625-4300

Faith-Based Residential Programs

Teen Challenge

268-0614

Men and Women, 1 year program

New Life Recovery Program

445-3787

Men only

Mountain of Mercy (Honeydew)

601-3403

Men and women, children considered

Inpatient Residential Treatment Programs

Humboldt Recovery Center

443-0514

Men and women accepted

Alcohol and Drug Care Services

268-0264

Men and women accepted

Outpatient Programs

Department of Health and Human Services AOD

476-4054

Healthy Moms

441-5220

(For pregnant and parenting women)

Eureka Community Health Center

442-4038

Kimaw Behavioral Health and Human Services (Hoopa)

(530) 625-4237

Free with Tribal ID

United Indian Health Services (Arcata, Fortuna, Weitchpec)

825-5000

For tribal members

Groups and Meetings

Alcoholics Anonymous

aahumboldtdelnorte.net

844-442-0711

Narcotics Anonymous

http://www.humboldtna.org/

(707) 444-8645

AlAnon

(for family members of addicts and alcoholics)

443-1419

Celebrate Recovery

(faith-based)

442-1784

Circles of Solutions

(Through the Betty Chinn Center)

407-3833

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023