[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

For the grand finale of a Sierra hiking trip this past August, we got up at 2:30 a.m. and left from Guitar Lake to summit Mt. Whitney for sunrise. There was a new moon that night, and the neon and incandescent civilization was far away. With no competing light in this rarified air more than two miles high, we emerged from our tent to skies ablaze with stars. There were so many bright stars that I had trouble picking out even the most familiar constellations. And the radiant band of the Milky Way was like a sparkling belt around the well-fed waist of the heavens. I was awestruck.

On the North Coast it can be easy to forget that these same celestial objects lie above our tenacious coastal marine layer. I had only lived in Humboldt County for a few years before I stopped looking up. My evenings in the Sierra rekindled my interest in the night skies.

Russ Owsley, president of the Astronomers of Humboldt group, confesses that stargazing along the coast is "difficult at most times," but his enthusiasm is infectious. He brushed aside my reservations. My goodness, man, you can't let a few clouds get in the way.

Owsley did have some welcome advice. "Dress in layers and dress warmly," he cautioned. He uses gloves with the fingers free. "Take some food and a good planisphere." Although smart phone aps have increasingly made this traditional star chart obsolete, I'm still old school. You don't have to invest in an expensive telescope. Binoculars can do a very good job of opening up the heavens. After all, the ancient Babylonian astronomers were incredible observers and did so without benefit of magnification.

I initially started by trying to plan my outings. I contacted Ryan Campbell, who teaches astronomy at HSU and graciously offered to include me on a weather contingent class trip to the HSU observatory on Fickle Hill. Of course, after a string of clear nights, our appointed date arrived concurrent with the first wet storm of autumn. Hmmm ... star gazing on the North Coast depends on your ability to seize the moment.

Later, a string of cold, clear nights presented my first opportunity for spontaneity. I quickly collected my binoculars and a guide to the autumn sky, and dutifully added enough clothing that I looked like a porcine Michelin Man. I headed to the Arcata Bottoms, where I was immediately mesmerized by the setting sliver of a moon. For the first quarter hour I was content to watch its descent over the greater Manila skyline. You cannot help but notice the ghostly image of the full moon extending from the illuminated crescent. This view always makes me think, admiringly, of Leonardo DiVinci who first conceived of the concept of "earthshine." One of the many great stories that accompany the study of the night skies.

Some years ago I had seen some of DaVinci's Codex Leicester, a collection of 18 sheets of paper filled with drawings and script covering a variety of scientific topics, on display at the Seattle Art Museum (Bill Gates owns this Codex). It included the section where Leonardo correctly suggested that we are always able to see the faint outline of the complete moon because of the light reflected off the Earth's oceans (actually most of the light is reflected by clouds). In fact, our own planet lights up the lunar night fifty times brighter than a full moon and produces the ashen glow. Leonardo's genius solved this riddle some 30 years before Copernicus suggested that the sun was the center of the universe in 1543 and 100 years before German astronomer Johannes Kepler proved DaVinci correct.

After watching the moon on that clear night, I spread out my blanket and positioned myself to watch the heavens. I had not realized just how much ambient light spreads from Arcata and Eureka. There is a good case to be made for driving to the vista point on Berry Summit or to the Kneeland Airport, where I headed for my second rather spontaneous outing. Yet I was still able to see a great deal. My active imagination bounced around with each noise from adjacent fields. There was cud chewing and scuffling by smaller denizens of the night. It took a while to settle in and focus my attention on the night sky.

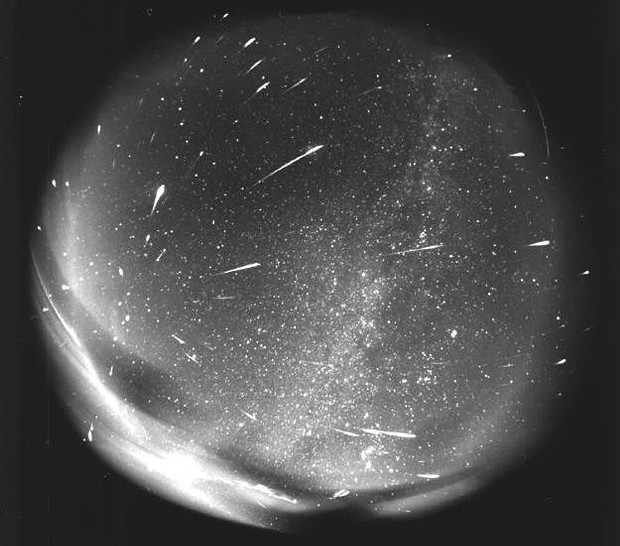

Patience was rewarded by several vivid meteorites with luminescent vapor trails. And perseverance helped me match much of my planisphere with what I was seeing above me. Ursa Major and Minor, of course. Delphinus, the dolphin, Cassiopeia, and Cepheus are distinctive. Hercules and Pegasus took me longer to identify. The International Astronomical Union recognizes 88 constellations, although many of those are not visible from the northern hemisphere and those that are change with the seasons. I pulled out my binoculars and spotted several well-known double stars. Satellites crisscrossed with a sense of urgency. They always seem rushed to me; out of sync with the rest of the night. Mankind's incongruous addition to the firmament.

All this in an hour or so. I had neglected to bring gloves and my fingers were yearning to wrap themselves around a warm cup of tea. There is something to be said for star gazing from the vantage point of a well-situated hot tub.

My later trip to Kneeland Airport, while above the clouds, was compromised by a mostly full moon. The night however, turned out to be much warmer and the tarmac of the runway shared its accumulated heat from the day. Not far from the airport, at Kneeland School, is one of three local observatories. (The others are HSU's Fickle Hill observatory and CRs campus facility). Using the 14 inch Celestron telescope and a 6 inch refractor, it is possible to get a glimpse into what Owsley had called "deep space," the home of galaxies, nebulae, planets and other celestial objects. This can best be done by attending one of the meetings or events hosted by the Astronomers of Humboldt at Kneeland School on the Saturday closest to the "dark of the moon." The group will also have telescopes set up at the Gazebo in Eureka during the Saturday, Dec. 1, Arts Alive -- weather permitting of course. It has an excellent website for both specific club information and general astronomical resources: http://www.astrohum.org/.

Several upcoming meteor showers will reach their peak at times when the moon offers minimal interference. The Leonids Meteor Shower, with its climax around Nov. 17-18, and the Geminids Meteor Shower (considered by many to be the best meteor shower in the heavens) with a peak around Dec. 13-14, should offer excellent celestial shows. EarthSky notes that while the Leonids have produced some of the greatest meteor storms in history (1966, most notably) with rates as high as thousands of meteors per hour, many years they are but a whimper.

It does not take but a night of peering into the skies to appreciate mankind's fascination with stars. Lord Byron called stars the "poetry of heaven." The clear night sky is part aesthetic and romantic, part spiritual and scientific. In a vast, infinite universe, it is a poignant reminder of our humanness.

more from the author

-

Building Trails and Resilience

An update on the virtual Trails Summit

- Jun 11, 2020

-

Throw Like the Irish

Road bowling for beginners

- May 14, 2015

-

Thar She Blows

Whale watching on the North Coast

- Mar 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in Get Out

Readers also liked…

-

A Walk Among the Spotted Owls

- Apr 27, 2023