[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

I was thrilled to run into my little cousin working at a gas station in Redway. After all, he'd been watering his meth-addled daddy's plants from the time he could toddle. Third generation of growers, I never expected him to get out. But there he was with his wide, cheeky grin, slinging high-octane coffee and unleaded gas, talking about going to College of the Redwoods next semester. I didn't hug him so much as tackle him to the ground.

I can count on one hand the number of boys in my generation who left my small Southern Humboldt hometown and went on to college. Some moved to town, some even further away. But most took their high school diploma back to the hills with them and took up the trade they'd been taught from grade school onwards. It's hard to blame them. A minimum wage job is poor competition for the kind of money a cash crop like illegal weed brings in.

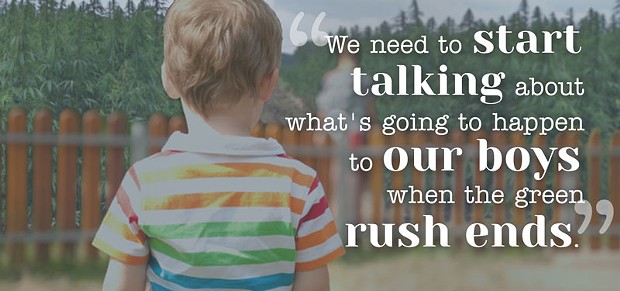

We need to start talking about what's going to happen to our boys when the green rush ends. We need to talk about it because they are just that, our boys, our boys in flat-brimmed hats and mud-covered trucks, our boys from Alderpoint to Honeydew to Orleans and all points in between. They grow the crop that translates to money that trickles down into our local stores and our local homes. Many are like my cousin, several generations into the industry and conscripted into its culture from birth. Many have never needed bank accounts or resumes. When the great experiment that is the wink-wink, nudge-nudge, hush-hush culture of illegal agriculture croaks its death rattle, brows will furrow over faltering businesses and diving home prices. Statisticians and entrepreneurs will discuss how to fill the gap. And an entire generation that came of age in a time of fast money will in all likelihood become inheritors of systemic poverty.

Grow culture is just that — a culture — with a culture's lore, etiquette and transitions and diffusions. The story of our boys is more complicated than a cautionary tale. For every one who ended up in jail, in prison or dead there's another who came out on the other side with a young family and a small legal business, all funded by many seasons of patient work and savings. And for every diesel dope mega-grow blighting the view from my kitchen window, there's a mom-and-pop mini-grow whose sole intention is to finance a simpler life.

But that simpler life is getting harder and harder to finance. A subtle exodus has begun — the folks who arrived on the tail end of the California green boom intent on making their nest egg are packing up. Others are falling behind on their land payments. Still others are scaling up to make ends meet, just as we face an unprecedented drought and the industry comes under greater scrutiny for environmental impact.

And our boys? I see them fixing their trucks instead of just buying new ones, the way they used to when they were high school graduates earning a lawyer's salary. I can't help but wonder what's going to happen to them once the bubble finally bursts. Will they go on unemployment? Will they get hired on by friends of friends and learn to punch a clock in the city? Will their skills and experience somehow transfer into the brave new world of legalized weed?

My little cousin, he got out but he didn't stay out. The last time I saw him he was climbing out of a new truck with a running board that came up to his waist. There were some gaps in his wide, cheeky grin. I still hugged him hard enough to break his ribs. I love our boys.

Linda Stansberry is a freelance journalist from Honeydew.

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

- More »