[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

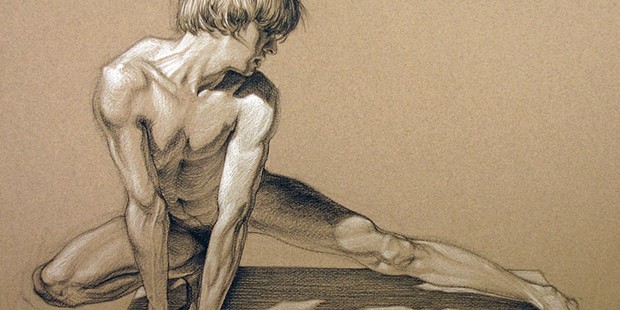

As you pass the Fifth Street storefront that's now home to Evolution Academy of the Arts, you might wonder where Eureka Studio Arts went. In fact, the art school and exhibition space was known as Eureka Studio Arts when it was under the direction of Micki Flatmo and Linda Mitchell. Artists Brent Eviston and his wife Sarah Fay Philips took ownership in October and changed the name. The new owners plan to continue the school's legacy of community engagement and accessibility, while expanding the range of courses to include more specialized classes in watercolor, oil pastel and animation — in addition to courses in the foundational skills of painting and drawing, which remain the backbone of the curriculum. Eviston calls Evolution an "atelier style studio school" where students learn to draw in the traditional way, through a step-by-step process based on study of a live model.

This month during Arts Alive, along with paintings by Guy Joy and a preview of February's figure drawing show, the academy hosts the third in an ongoing series of community art projects. Participants create work on the theme of "Abstract Color," and it's free and open to all. Evolution staff will provide instructions and materials, and anyone who gives it a shot can enter to win gift certificates toward Evolution classes.

An upcoming animation class builds on Eviston's longstanding interest in stop-motion. Gallery-goers will remember the animated drawings Eviston made in collaboration with Steven Vander Meer shown last year at Eureka's Piante Gallery. Those works drew inspiration from 19th century technologies like the zoetrope, the spinning cylinder that creates "moving pictures." Graphite drawings quivered, whirled or gyrated, to uncanny and memorable effect via stop-motion. That show illustrated the artists' conviction that drawing is not just a tool or an arcane skill, but a vital way to interpret the observed world. The same message informs Eviston's approach to teaching.

"Art is not a talent," Eviston says. "It's a skill, and it can be learned. People often say, 'Oh, I can't draw, I'm not talented,' but drawing from life is a skill like any other." Eviston aims to bring this empowering message to the Eureka masses via affordable, accessible classes designed to be welcoming to beginners of any age, with little or no prior experience.

In conversation, Eviston emphasizes that students need to demystify drawing — and lose the mental baggage associated with concepts like "talent" and "genius" — in order to be able to approach it with creative freedom. Competent draftsmanship is no more the effortless product of talent than a bull's eye in archery or a black belt in martial arts. Mastery derives from hundreds or thousands of hours behind the pencil.

In traditional studio classes, students hone their powers of observation through a disciplined, step-by-step process that sharpens the connection from eye to hand. It has changed little since the Renaissance, but Eviston argues persuasively for its contemporary relevance in a 2012 TED talk posted on YouTube titled "How Learning to Draw has Taught Me How to Live."

Because drawing is a time-consuming process that inevitably incorporates mistakes, it exposes learners to a process in which errors must be incorporated. It models a mode of creative thinking that Eviston thinks may be particularly important in the fluid, unstable, contemporary workplace.

"There's a sense that people often get, when viewing an old drawing, that it was done because the camera had not yet been invented," Eviston says. "But the act of drawing is much closer to solving a mathematical equation than to taking a photograph. Drawing is an active way of engaging reality — of observing, analyzing and recording it, with the possibility of reimagining it."

Drawing also helps us understand the value of errors. "Too often people experience a sense of shame regarding their mistakes, Eviston says. "But imagine what might have been different in your life if your mistakes in any area had been viewed as normal, temporary and holding vital clues to your eventual success."

But how do you get students to let go of that critical interior voice?

"First, you have to get past the myth of talent and accept that art is a skill like any other," he says. "It's like learning to drive. When drawing or painting, you have to think of an act in multiple ways at once. I don't just put students in front of the model and say, 'OK — draw!' I try to isolate the steps and treat each one independently."

Eviston stresses learning lightly first and accepting that those first lines won't necessarily be right. But every line offers the opportunity for correction: the opportunity to do over, to translate optical information more vividly with greater accuracy. "It's a process. And over time, you correct your mistakes. Over time, you darken and solidify the lines. Drawing is a lifelong process," he says. "The best students are not the ones who get it right the first time; they're the ones with the fortitude to persevere, and keep on."

Eviston himself began drawing at a tender age, like most children, "and just never stopped. Nobody starts off good at drawing!" he laughs. "But, it was always what I really enjoyed doing. And really enjoying the process was important. If I had a particular strength, I would say that it was this: I was not too hard on myself. If I didn't get it right the first time, I would just keep trying."

When you concentrate on making a record of your visual perception, it creates a meditative pleasure outside the realm of language. This pleasure remains key to Eviston's practice. "The observational aspect of engagement with the subject is very meditative. Any other time of day an orange sitting on a table is ... an orange sitting on table. But when you start to pay attention to that orange, you develop a relationship with it. You feel the form. You become attuned to the smallest shifts of light and color." Through paying attention, one actually learns to see more.

The deep, sustained absorption that drawing demands is a valuable counteractive to the distracted multi-tasking of "screen time" at home and in the workplace. It's easy to understand why Eviston wants to reach the widest possible audience. Through the classes and the community projects, Eviston is "calling for a widespread visual literacy — whether it's on paper, tablet or any other form of technology. And visual literacy begins with drawing."

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »