The Traditionalist

George Blake's retrospective at the Gou'dini Native American Arts Gallery

By Gabrielle Gopinath[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Artist George Blake has used needles finer than a hair's breadth to sew brightly colored songbird feathers into intricate patterns. He has strung bows, carved elk antlers into traditional Hupa spoons and shaped second-growth redwood trunks into dugout canoes. The things he makes document moments in a lifelong encounter with the old ways of believing and existing in the world, ways that were the norm in northern California for thousands of years prior to the 19th century arrival of white settlers.

Blake, who is Hupa and Yurok, was born in 1944 on the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation. His art continues to exude awe for that beautiful place and love for the spirit of its resilient people. In the course of a career now in its fifth decade, Blake has used painting, woodcut, sculpture, jewelry and regalia-making to evoke aspects of his great theme — the experience of a contemporary Indian artist regarding his ancestral heritage.

Blake makes extensive use of traditional Hupa and Yurok materials. Many of the textures, colors and forms in the artworks on display are deeply and enduringly familiar to indigenous people of northern California. Effects range — from the rough, matte surfaces of fired stoneware to the smooth, cold heaviness of antler and bone, from the opalescence of abalone to the dark luster of carved and polished yew.

Although titled George Blake: A Retrospective, the exhibition at Humboldt State University's Gou'dini Native American Arts Gallery makes no attempt to periodize Blake's work. Early sculptures like "Baby in a Basket," from 1974, are presented alongside elk antler spoons made in 2016 without benefit of commentary. Viewers wondering how Blake's work has been shaped by cultural context or how his work in different media evolved over time will leave this exhibition none the wiser. Nevertheless, Blake's work transcends.

Among other things, it presents a beguiling opportunity for projection, surely one of the higher purposes behind regalia-making and traditional crafts. None of us can know what it was like to live within the fully integrated Yurok past, when the place now known as Woodley Island was the beating heart of the world. But we can rest our eyes upon things that those people would have looked at and use technologies they would have used. When we do this we take part in a dimension of their experience. There is a richness in the visual and tactile experience of these materials that is rare in the context of our daily lives.

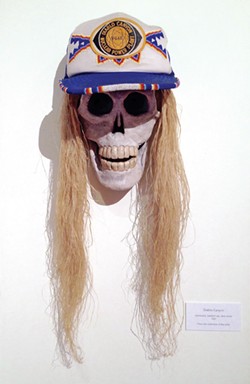

Not all of Blake's work is bounded by tradition. A series of sculptures shaped like tall, skinny humanoid totems exude the mordant funk I associate with the dirtier strands of West Coast Pop (think Bruce Conner's pantyhose-bestrewn assemblage, or Ed Kienholz's horror-core tableaux). They mash up traditional and decidedly non-traditional substances, some with bodily and animal origins. Elk skin, wolf skin and shredded money are only some of the substances that go into making "The Corporate Wolf," Blake's 1983 satire of Wall Street greed. The crisp blonde tendrils of hair dangling on either side of the grinning death's head titled "Diablo Canyon" are made from deer sinews.

Some of these pieces delve into autobiography, others into social critique. "How Do You Keep Him on a Reservation When He's Been to Paris?" — a self-portrait that alludes to Blake's time in the U.S. Army from 1963 through 1966 — gives us the young artist as a mustachioed hipster in beret and scarf, its title an American Indian-centric riff on a jazz hit recorded by World War I-era bandleader James Reece Europe about American G.I.s' experiences abroad.

While the sculptures allow personal hand to take precedence, individual style is subsumed within a traditional approach to design in other areas of Blake's work. The intricate crosshatch patterns he engraves in an elk antler purse look much as they would have in a Hupa purse made 100 years ago. The geometric shapes he uses to pattern paintings and stoneware ceramics derive from traditional beadwork designs. The dugout canoes he has made are based on extensive research into traditional boatbuilding practices, including oral instruction from tribal elders.

One of those canoes can be seen in the Humboldt State University Library, located a five-minute walk across campus from the Gou'dini Gallery. It's well worth a visit there, even though it is on display in a dark, high-traffic hallway on the first floor that makes viewing a challenge at best. Just stand and let the passersby flow around you. The canoe will be resting there silently, waiting for you. Blake crafted it 25 years ago with the help of his nephew and a team of student apprentices. Its heavy, bladelike form is dark and solid. The redwood exudes a satiny glow that will still be apparent even in the fluorescents' overhead glare. The lines have an intuitive rightness. You can tell this boat wants to be on the water.

The Gou'dini Gallery is located in the ground floor of Humboldt State University's Behavioral and Social Sciences Building. George Blake: a Retrospective will be on display there through Dec. 3.

CORRECTION: The canoe crafted by George Blake has been relocated to the second floor, where it is placed on a new pedestal built especially for it. It is much easier to enjoy there.

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »