[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Arts Arcata audiences are spoiled for choice this month. Up on the hill of higher learning, Humboldt State University's Gou'dini Native American Arts Gallery features an information-intensive show that documents the fight to undam the Klamath. Meanwhile, Edson Gutiérrez shows tattoo prototypes downtown at Gallery Métier, on H Street right across from Bubbles.

The Gou'dini group show is titled Stories of the River, Stories of the People: Memory on the Klamath River Basin. Curated by HSU history grad and Hoopa Valley Tribe member Brittani Orona, it features paintings, oral history and documentary video made by members of California Indian tribes of the Klamath River Basin.

Upon entry, viewers encounter a banner by Julian Lang, emblazoned with the single word "Ithivthaneen'aachip." The melodious Karuk designation literally means "the Center of the World," but it can also be simply translated as "Karuk country." In the background, a brightly colored landscape of abstract symbols and native Californian words unfolds.

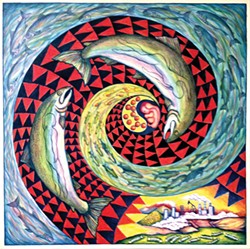

The banner is flanked by brilliantly patterned paintings of salmon by Lyn Risling, posters by Annelia Hillman and documentary photographs by Regina Chichizola. Viewers are invited to contribute memories of the river to a collaborative message board, and a documentary video projected on one wall shows activists speaking about the grassroots fight for river restoration spearheaded by members of Klamath Basin tribes.

A brief primer in local environmental activism is probably necessary here, in order to refresh longtime residents' memories and bring newcomers up to speed. In summertime, the mass diversion of Klamath water to Oregon farmers and ranchers via the river's four dams make for unnaturally hot, stagnant river water depleted of oxygen. These water conditions have repeatedly proven toxic to resident populations of salmon, steelhead and lamprey. Tribal members have been instrumental in the decades-long movement advocating for the removal of these dams.

In 2002, overheated, toxic river water sent 77,000 mature Chinook and Coho salmon belly-up, eliminating a significant chunk of those species' Klamath-region breeding populations in a single, devastating event. The fish die-off spurred many witnesses to take political action with the aim of preserving the river ecosystem, along with the rich repository of native rituals, traditions and cultural practices that depend on it. Several speakers in the video name this as the event that brought them to full recognition of the river's crisis status.

"Dams choked the river more, there's been less flow. It's changed how the river looks, smells, how the fish tastes," one speaker observes. "Tribes have to request that water be let down into the river to do the ceremonies, because now there is not enough water to do the ceremonies, not enough draft for the boats."

In 2010, a swath of diverse groups that depend on the Klamath — from ranchers to tribes and farmers to fishermen — came together and forged a compromise, the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (and a pair of subsequent pacts) that would have removed the four Klamath dams that have been blocking the free flow of Klamath water since the first was erected in 1903. The agreements failed to get the necessary approval of Congress, but stakeholders recently announced a new pact they hope will revive the agreements and see the dams removed in 2020. Many hope uncorking this century-long stoppage will return some measure of balance to the ecosystem, protecting decimated fish populations from further damage and giving them a chance to recover.

The long struggle that led to this landmark Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement is chronicled here by contemporary photographs and video, interspersed with reproductions of photographs of California Indians made in the early 20th century by photographer Edward Curtis. Curtis's pictures are paired with latter-day photographs of similar subjects. For instance, the image of a Hupa fisherman from 1923 is hung side-by-side with Chichizola's 2005 photo of a boy fishing with similar tackle.

The installation shows us that the indigenous people who lived along the Klamath in the past share important aspects of their identity with their descendants who live along the river's banks today.

The photographs' ability to convey this message is somewhat impeded by the fact that both the contemporary digital inkjet images and the silver gelatin prints from the 1920s have been blown up and reproduced on foamboard, at similar scale. This presentation emphasizes shared content, but obscures the differences between mediums and we lose the chance to explore them as objects through close looking.

Regardless, there's much to be learned in this valuable exhibition. Tribal members' video testimony about the river is forthright and affecting. Risling's mandala-like salmon paintings and Lang's banner seem to vibrate with intensity, thickening the atmosphere around them.

One of the principles this exhibition clarifies is that rivers are tough to depict. Systems are hard subjects in general. The nature of a system is to be interconnected and plural, while the canvas favors figures that isolated against a ground. And a system as complex as the Klamath exists as a dynamic situation, more than a discrete subject. Like the philosopher Heraclitus observed, you can't step twice into the same river, "for other waters are ever flowing on to you."

Meanwhile, Edson Gutiérrez is showing works on paper intended as tattoo prototypes at Gallery Métier, a spirited little pop-up space in downtown Arcata. Owned and curated by Joliene Bourassa, the gallery takes its name from the French word for "trade." In its initial months of operation Bourassa's programming has displayed real commitment to the principle behind the name by showing the work of artists working in folk genres that remain distinct from the contemporary art mainstream, like tattoo.

Gutiérrez, an apprentice at Sailor's Grave Tattoo in Eureka, respects the tradition by showing classic motifs like anchors, roses, empty bottles and broken hearts — all executed in a thick, fluent line that lends gravitas to even the most familiar subjects.

Some of his more elaborate designs enter stranger territory. A sweet-faced femme fatale wears a fancy headdress that seems to have been freely interpreted from historical Aztec models. The lady is no joke: She looks like Carmen Miranda's more intimidating cousin, with the glossy curls of her piled-up hair imperfectly concealing an alarming assassin's cache that includes live snakes, a sinister-looking gurka khukri knife and (I think) an octopus.

The two shows make a surprisingly effective double feature. If the complexity of rivers is beyond our comprehension, tattoos do the opposite. They are eminently portable, fitted to our personal specifications, priced accessibly and as public or as private as the bearer wishes. Like rivers, tattoos exist in time. But rivers exceed our grasp, while tattoos seem poignant because they are so human it hurts. See these shows while you can, before they flow and fade away.

Stories of the River, Stories of the People: Memory on the Klamath River Basin shows at HSU's Gou'dini Native American Arts Gallery through Feb. 20 with a closing reception Friday, Feb. 19 at 4:30 p.m.

There will be an opening reception for Edson Gutiérrez at Gallery Métier during Arts Arcata on Friday, Feb. 12 at 6 p.m.

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »