The Gray Whale Die-off

As strandings continue, scientists scramble to figure out why

By Kimberly Wear [email protected] @kimberly_wear[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

With a bulbous upper jaw jutting out from an elongated head dappled by a patchwork of barnacles, the gray whale may not cut the same sleek figure as its oceanic cousin — and mortal enemy — the orca, which recently made some forays into Humboldt Bay.

But the whales named after their slate coloring can be easy to spot from shore during their twice yearly jaunts past the North Coast, sometimes showing off with spectacular displays of breaching or a simple flip of the tail fluke.

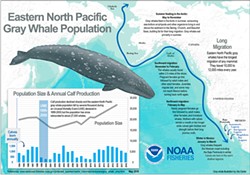

Currently returning from a winter break in the warm water lagoons of Mexico, where a new generation was born, gray whales are nearing the last leg of their journey back to the cool Arctic waters where they will spend the summer feeding and fattening up for next year's trek.

The marathon migration — traversing some 13,000 miles — is believed to be the longest of any mammal. But in recent months, something has gone terribly wrong.

Gray whales, the official state marine mammal of California, have been washing up dead in such alarming numbers that NOAA Fisheries recently declared what is known as an "Unusual Mortality Event," freeing up resources and triggering a multi-faceted scientific review to try to figure out why.

"The significant die-off of these animals that we've seen this year demands an investigation to determine what might be causing the die-off, such as environmental conditions, disease or human activities," says Deborah Fauquier, a veterinary medical officer with NOAA's Office of Protected Resources.

More than 150 of the marine giants have been found dead on beaches from Mexico to Alaska since January, a dramatic upswing in deaths not seen in two decades. More are expected in the coming weeks and months.

And because whales — especially emaciated ones — are more likely to sink into the ocean depths than wash ashore, marine biologists believe the reality is far worse than what's been found.

"It's a number that's difficult to quantify," says John Calambokidis, a marine biologist studying West Coast whale populations with the Washington state nonprofit Cascadia Research in Olympia, noting the 150 number could represent as few as 10 percent of the actual deaths. "The event is still very much ongoing."

What has been established is that most of the stranded grays seem to be starving.

"We know many of the whales have been skinny and malnourished, and that suggests they have not gotten enough to eat during their last eating season in the Arctic," Mark Milstein, a public affairs officer with NOAA, said during an announcement of the mortality declaration late last month.

That was the case with the two whales discovered in Humboldt County in April and May — an adult female observed in heavy surf near Scotty's Point in the Trinidad area and an adult male that washed up on the oceanside of the South Spit.

The whales were "emaciated" and bore no obvious signs of being hit by a ship or other "human interaction," says Dawn Goley, a zoology professor at Humboldt State University and the Northern California coordinator for the Marine Mammal Stranding Network, who responded to both scenes.

"There was none of that," she says. "So, it seems it's mostly along the same lines as the others that died along the Pacific Northwest."

That, Goley says, raises the question: Have the food resources dwindled for some reason or is there simply not enough food to go around?

"Hopefully, we'll be able to figure some of that out," she says.

The local network has teams scouring 31 beaches in Humboldt, Del Norte and Mendocino counties each week, with every found whale helping to build another data point as scientists strive to unlock the mystery of the high mortality rate.

But even that level of effort leaves vast stretches of shoreline unchecked in the isolated reaches of the North Coast.

It's important, Goley notes, to reach the whales as soon as possible to collect samples in order to glean as much information as possible before nature takes its course in the form of decomposition and scavengers.

The network collaborates with as many organizations as possible, including the Bureau of Land Management and state and national park employees, Goley says, but it always needs more help. And, that's where the public comes in.

"The quicker people call (the stranding hotline to report a washed-up whale), the quicker we can get there," she says. "The more eyes the better. ... The more of a community effort we can get, the better the understanding we can get of what is going on."

Goley notes the Guadalupe fur seal has been facing a similar dilemma to the gray whale since 2015, washing up alive and dead across coastal California in numbers NOAA describes as "eight times higher than the historic average."

"Those stranding are mostly weaned pups and juveniles (1-2 years old)," the NOAA mortality event page for the seals states. "The majority of stranded animals showed signs of malnutrition with secondary bacterial and parasitic infections."

Guadalupe fur seals found alive are sent to The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito or Sea World in San Diego for treatment.

Unlike the gray whales, which can reach lengths up to 49 feet and weigh in at a boisterous 90,000 pounds (with females slightly larger than males), Guadalupe fur seals are "quite slight" at 3 to 7 feet and perhaps a few hundred pounds, making them harder to spot, Goley says.

"They can be preyed upon pretty quickly," she says.

The animals may differ greatly in size but both were nearly hunted to extinction a century ago with the gray whale, now often thought of as a gentle giant, earning the name "devil fish" for fiercely fighting back when harpooned in a grisly hunt to provide lamp oil.

The entire population of Guadalupe fur seals, once coveted for their luxurious pelts as well as oil-rich blubber, was thought to be lost until a small colony was discovered in the 1950s.

Both species are recovering from near decimation after protections were put in place but both are now facing a different battle, although any role humans may have played this time around is still unclear.

While data is now being processed in the case of the Guadalupe fur seals, the search for what is causing the unusual mortality event for gray whales is just getting started.

An investigation into a similar gray whale die-off two decades ago found starvation to be a "significant contributing factor," according to the report, but no conclusion was reached on why the whales were unable to find enough food.

One question raised today is whether the gray whale population of 27,000 — one of the largest recorded in recent decades — has exceeded its so-called "carrying capacity," or the ecosystem's ability to support the burgeoning population.

David Weller, a research wildlife biologist with the Southwest Fisheries Science Center, says that is one theory but also notes that "carrying capacity is not a set ceiling but it is a shifting threshold."

"The capacity of the environment to support a whale population varies from year to year," he says, adding that as dire as the die-off sounds, the whales should be able to bounce back.

Another potential factor is the interplay between the early melting of Arctic ice due to climate change and how that impacts the shrimp-like amphipods that make up the whales' primary food source.

"It becomes a complex question," says Sue Moore, a biological oceanographer at the University of Washington, adding the whales may eventually need to "shift to other prey."

One aspect being researched is whether "sea ice provides fertilizer to those amphipods beds" amid the sediment of the Arctic seafloor, Moore says, noting that the beds appear to be shifting northward.

"Right now, we are just piecing it together as we can," she says, noting there are a number of potential factors, including environmental changes and disease, that will be examined in the coming months.

Like Goley, NOAA Fisheries officials and marine biologists are asking for the public's help by reporting distressed, floating or beached whales, while also emphasizing that people should not approach the animals, which is against the law.

And with more strandings expected, NOAA has even put out the call to property owners in the Pacific Northwest to volunteer sites where the unusual number of whales can be allowed to naturally decompose.

Meanwhile, marine biologists will continue to assess the situation as they collect samples and pore over data in an attempt to unravel what is behind the massive die-off.

"The No. 1 priority is learning all we can from the stranded animals," Weller says. "We've got our fingers on the pulse and I would say we want to continue to monitor it closely. The expectation is we're halfway into to this."

Kimberly Wear is the Journal's assistant editor. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Speaking of...

-

High Risk of Sneaker Waves on Saturday

Feb 25, 2022 -

Orca vs. Whale

Jun 24, 2021 -

The 25 Days of Crustmas

Dec 19, 2019 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

Dust to Dust

The green burial movement looks to set down roots in Humboldt County

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Our Last Best Chance

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Judge Rules Arcata Can't Put Earth Flag on Top

- Apr 5, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023