The 200th Victim

Humboldt County's response to the 1918-1919 and what it teaches us a century later

By Jerry Rohde[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

In 1918 my dad, part of the U. S. Army's First Division, was on a troop ship bound for France. The soldiers on board slept in bunk beds. My dad had a lower bunk, and each morning he would kick the bunk above him to wake up the soldier sleeping there. One morning he kicked — and almost broke his foot. His friend had died in the night from the raging influenza epidemic and his body was hard as a rock.

The illness swept through the ship. My dad was detailed to take the victims' soiled bedding to the ship's laundry. He couldn't get any closer to the illness than that so he took another soldier's advice and started chewing tobacco to stifle the contagion. My dad never chewed tobacco again but, 40 years later, he still credited it with saving his life.

Other soldiers were not as fortunate. On Aug. 25, "somewhere in France," Clyde Hemphill, a soldier from Blue Lake, died from the influenza. He was the first person from Humboldt County to be claimed by what had become a pandemic.

The first, relatively mild, wave of the illness came in the spring of 1918. By August, the second wave had hit and it was much more lethal. Some sources believe that the Army's Camp Devens, in Massachusetts, was a starting point for the new attack. It soon became clear that soldiers were among the hardest hit.

In June of 1918, Joseph McCarthy left his family in Eureka, traveling to a training facility for the Army's radio corps. McCarthy first went to Corvallis, Oregon, then to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and finally to Camp Meade, in Maryland. There the influenza caught up with him and he died on Oct. 10.

Shedrick O'Hara, a butcher from Eureka, was claimed by the illness more quickly. On Oct. 14, he left Eureka for Army mechanics' training in Spokane, Washington. O'Hara contracted the flu while on the train to Spokane. Once there, he was carried by stretcher to the Fort George Wright Army Hospital, where he died. While alive, O'Hara had never worn his Army uniform but his body was dressed in it for the trip home.

By then the pandemic had come to Humboldt County. The first four cases were reported on Oct. 12. The victims were taken to a "safe house" in Eureka where they would receive care while under quarantine. Despite this precaution, the influenza vector was already at large. By Oct. 14 there were 19 cases in Eureka. Twelve days later, the total was estimated at 500. By mid-November there were 1,282 cases, with 45 deaths. The city's population then was about 13,000, meaning 10 percent of its residents had contracted the flu.

In late October, individual Humboldt County communities took action against the growing epidemic, ordering lodges, churches, schools, theaters and libraries to close. All public meetings were canceled. Towns began passing ordinances requiring the use of gauze masks when in public. On Nov. 6 the Ferndale Enterprise carried a banner headline announcing, "It is Unlawful for Any Person to Appear on the Streets of the Town of Ferndale without a Mask Covering Nose and Mouth."

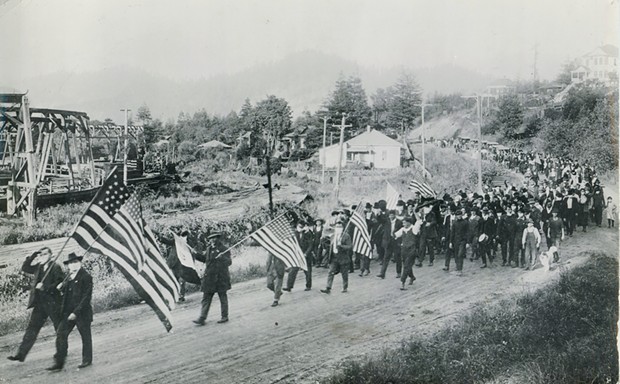

The following day a countywide face mask ordinance went into effect. In at least one instance, it was almost totally ignored. When World War I ended on Nov. 11, citizens marched from Rio Dell to Scotia in a celebratory parade. A photo of the event shows a few participants wearing gauze masks but most are crowded close together, maskless, with some even holding hands. The concept of sheltering in place did not yet exist.

The pandemic had by then hit Scotia so heavily that the Pacific Lumber Co. turned the Scotia Men's Club into an emergency hospital. In a little more than two weeks, eight PL workers had died.

If some people were careless or disdainful of the safety rules, others displayed ingenuity and compassion in dealing with the epidemic. Cal Munther, the superintendent at the California Barrel Co. camp east of McKinleyville, instituted a quarantine system for his workers. If any of them went to town they were segregated in a special tent when they returned. They had to eat their meals separately and work alone to avoid the possibility of transmitting the virus to other workers.

In Fortuna, Mr. and Mrs. A. G. Campbell turned their home into an emergency hospital. Fortuna's Red Cross Auxiliary provided the Campbells with bedding, food and other necessities. When it became apparent that more healthcare workers were needed, Mrs. Foster at the Arcata Fraternal Hospital organized a group of 10 emergency nurses and sent them throughout the county. Before the epidemic was over, at least three Humboldt County nurses had died from the flu.

The Sisters of St. Joseph converted their convent into a temporary hospital but they knew more facilities were needed. They convinced the Eureka City Council to temporarily reopen the Northern California Hospital, which had recently closed. In 1920, the facility became St. Joseph Hospital after Eureka citizens urged the sisters to continue the healthcare work they had initiated during the epidemic.

Ferndale had taken strong steps to fight the flu, even fumigating stores and public places. At first these tactics seemed to work, since by Nov. 1 the town had only a few cases of influenza and no deaths. By the end of the year, with the epidemic diminishing throughout the county, it appeared that Ferndale had dodged the bullet. Like other places in the county, the city began to relax its restrictions.

It proved to be too early. New cases began to appear in Ferndale in January. The town had no hospital and two of its doctors became sick. Two homes were converted into emergency hospitals and a Eureka physician came to Ferndale to treat patients. By the end of February, this late-wave epidemic had subsided. By then, 12 of the town's residents had died.

It's not certain how many Humboldt County residents were killed by the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, but the names of 199 victims appeared on a list compiled in 2018. There may have been more but as far as we know there was never a 200th victim.

One-hundred-and-one years later, we may ask, Why not? What kept the county from having more deaths? It probably wasn't because thousands of residents started chewing tobacco, like my dad. Nor was it because Humboldt County had an exemplary knowledge of epidemiology. If anything, it was because countless individuals, caught in an apocalypse they hardly understood, acted with care and compassion for the members of their community. They wore their face masks and they understood the intent of these primitive objects, which was to lessen contact and contamination, so they avoided gathering in public. Healthcare workers risked their well-being and perhaps their lives by tending to the sick. Each town or city, in the absence of guidance from the federal government, did what it could to protect its citizens from a modern-day plague.

No solution was perfect. No action ended the epidemic. But the impulse to help others was always present, and there were always people willing to act on that impulse — to act, as best as they could, based on the knowledge they had, to avoid there being a 200th victim.

A century later, we can all do the same.

Editor's note: This story relies heavily on information from Matina Kilkenny's pieces in the Humboldt Historian and from Jeff Coomber's Barnum essay

Jerry Rohde is an ethnogeographer and historian who writes about Humboldt County and prefers he/him pronouns. His most recent book,

Both Sides of the Bluff, is a history of the lower Eel and Table Bluff.

Speaking of...

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

more from the author

-

This Land Is Their Land

- Sep 1, 2022

-

The Women Behind the Trees

Laura and James Wasserman's Who Saved the Redwoods? The Unsung Heroines of the 1920s Who Fought for Our Redwood Forests

- Jun 6, 2019

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023