'Profoundly Disturbing'

Dick Magney was preparing to die on his own terms, then the county of Humboldt stepped in

By Kimberly Wear [email protected] @kimberly_wear[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

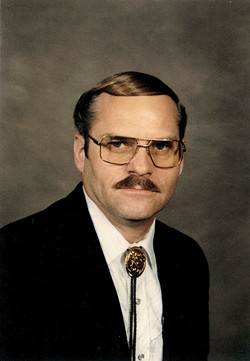

Dick and Judy Magney knew his life was drawing to a close when he was admitted to St. Joseph Hospital in February of 2015. The 73-year-old former truck driver was suffering from a series of incurable long-term ailments. His quality of life was waning. Pain had become a constant companion.

The couple had prepared for what lay ahead, having gone to an attorney four years earlier to draw up an advance health care directive that set out his final wishes. If Dick Magney could no longer make decisions for himself, his wife was designated to make them for him, with his sister as an alternate.

"I want to live my life with dignity and for my loved ones to have pleasant memories of my final days. Thus, I wish to be allowed to die without prolonging my death with medical treatment ... that will not benefit me," his instructions read.

Together with a team of doctors at St. Joseph, the Magneys charted a course of care that would keep him as comfortable as possible without invasive measures, which included discontinuing antibiotics for a heart valve infection.

Then, without warning, came notice that Humboldt County Adult Protective Services had been granted temporary jurisdiction over Dick Magney's medical decisions. The previously agreed upon palliative care route was reversed.

While that temporary order was later withdrawn, another would follow, this time an ultimately unsuccessful petition for a conservatorship over Dick Magney's affairs by the county's Public Guardian Office.

Meanwhile, the couple faced a new kind of struggle. It wasn't for Dick Magney's survival but for his ability to make the most personal of decisions: the right for him to die on his own terms.

It's a struggle the Magneys ultimately won after the county of Humboldt was found to have overstepped its bounds, to have deliberately mislead the court and intentionally concealed evidence in filings by Deputy County Counsel Blair Angus to wrestle temporary control over Dick Magney's treatment away from his wife.

An independent court investigator called the county's actions "inhumane" and "appalling." A law professor described the case as "disturbing." Allison Jackson, the attorney who represented the Magneys, said it was simply "unfathomable."

A panel of appellate court justices did not mince words in a recent decision holding the county of Humboldt responsible for the attorney's fees that Judy Magney incurred while challenging the forced medical treatment of her husband.

"We cannot subscribe to a scenario where a governmental agency acts to overturn the provisions of a valid advance directive by presenting the court with an incomplete discussion of the relevant law and a misleading compendium of incompetent and inadmissible evidence and, worse, by withholding critical evidence about the clinical assessments and opinions of the primary physician because that evidence does not accord with the agency's own agenda," the opinion states.

"No reasonable person, let alone a governmental agency, would have pursued such a course."

Meanwhile, the county continues to dig in its heels in the case despite the judicial rebukes. Last month, county counsel filed a letter asking the California Supreme Court to depublish the appellate opinion.

"This was a difficult case for all involved, with no easy answers and no winners," county spokesperson Sean Quincey said. "While we respectfully disagree with the court's findings, we do not intend to re-argue the case in the court of public opinion. Due to privacy laws and regulations, we are unable to comment further."

A little more than two decades before arriving at St. Joseph Hospital, the Magneys had been celebrating the start of their new life together.

Mutual friends set the couple up during a party in 1992. Judy was 47 at the time and Dick was 51. Neither had previously thought marriage was going to be in the cards for them. They hit it off right away.

While they initially lived 375 miles apart — with Judy in Long Beach and Dick in Mountain View — they visited each other over the ensuring weeks. Within six months they exchanged vows in an Anaheim wedding chapel.

On their honeymoon, the couple drove up the California coast and stopped in Humboldt County, where Dick Magney had ventured before on camping trips. He made another proposal to his new bride: Let's move here.

"I said, 'Sure,'" Judy Magney recalled during a recent interview in Jackson's office. "I was ready."

By January of 1993, they were settling into their modest home in Carlotta with enough property for Dick Magney's many collections, which ranged from the wood stoves he worked on as a side job to 1950s travel trailers.

With the kind of quiet timbre to her voice that is normally reserved for libraries, Judy Magney became more animated as she described her husband of 23 years who died in October of 2015, one month past his 74th birthday.

He had, Judy Magney noted with a smile, American Pickers "tendencies," recounting the time he called her at work because he had found a door from a submarine. He was so excited he could barely speak.

"He had cars, too," she said, adding that one of his prized possessions was a black Jaguar sports car, a picture of which he kept in his wallet, while he kept Judy's displayed in the vehicle.

"Oh gosh, he had a lot of hobbies," Judy Magney said, adding her husband was also a gifted painter.

Every year he grew his own corn so he could use the stalks for Halloween decorations. Both born-again Christians, the couple shared a strong belief in their faith and a love for working with their hands. For her part, Judy Magney is an avid baker who enjoys sewing her own clothes.

A self-described "stubborn Swede," Dick Magney arrived in the United States by ship with his family at 5 years old. The Navy veteran liked peanut butter, fast cars and going out on the ocean. A World War II movie buff, his favorite film was Tora! Tora! Tora! — the historic reenactment of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

"He told me once that wished he'd been born 100 ago," his wife said. "He liked everything old."

"He loved to joke around," she said, adding that his Whoopee cushion remains in a desk drawer at their house. "I just plain old miss him. He was a very kind man. He wouldn't hurt a fly. He just adored me. I just miss him."

When the conversation turned to the couple's legal battle with the county, the petite woman with a bob of gray hair who looks 20 years younger than her 71 grew even quieter. At times she only nodded in reply to a question, or paused to turn away for a moment before answering.

"I'm just glad they found in favor with us," Judy Magney said of the appellate court's decision. "It's bad enough when someone is sick and you are dealing with everything that is happening with them. To have all those additional things go on was horrible. It was awful."

It all began with a mandated reporter's call to Adult Protective Services soon after Dick Magney was admitted to the hospital that day in February.

There's no dispute that his situation was grim. In addition to chronic health issues, he was suffering from malnutrition — likely related to his heart valve infection — and pressure sores that developed during long bouts in the bathroom due to colon problems. He also had, according to court documents, terrible hygiene.

An investigation into the possibility of caretaker neglect began in March of 2015, after Dick Magney's treating physician Stephanie Phan had already determined he was unlikely to "bounce back" even if all of his underlining medical conditions were treated in a "full-court press," according to court documents.

In the unlikely event Dick Magney would recover, Phan believed the prognosis was a "really terrible quality of life."

Adult Protective Services assigned public health nurse Heather Ringwald to investigate the call. She spoke with Dick Magney, whom she reported to be confused, as well as Phan, who told her that she agreed with the course of palliative care decided in consultation with other doctors, the patient and his wife.

Judy Magney provided Ringwald with a copy of her husband's written advance care directive, which specified that he did not want his life prolonged by non-beneficial treatment.

Ringwald admitted in testimony, according to the appellate court, that she "personally disagreed" with Phan and that she and her supervisors decided to "challenge" the doctor's clinical assessment of Dick Magney's condition and his mental capacity to choose palliative care.

The county has asserted there were questions about whether Judy Magney was following her husband's wishes coupled with concerns that Dick Magney had been neglected prior to his hospitalization. No calls were made to Dick Magney's sister, his alternative designee, who would later testify she supported Judy Magney's decisions.

But when Deputy County Counsel Blair Angus filed a petition with the court to force treatment in March of 2015, there was no mention of Phan — Dick Magney's treating physician and the designated medical authority under the Health Care Decisions Law — nor her findings that further treatment was futile.

Instead, the county presented what the appellate court later described as an "appallingly inadequate" request with "glaringly incompetent and inadmissible evidence" and "multiple levels of hearsay."

That included an assessment from Dick Magney's VA physician — who by then had not seen him in months and was not involved in his hospital care — that stated Dick Magney could die without treatment.

Based on the information that was provided by the county, a judge issued a temporary order for medical intervention. Judy Magney challenged the order and it was withdrawn. The Public Guardian's petition for conservatorship that followed — basically a request to take control of Dick Magney's financial and medical decisions — was briefly granted before being denied by a judge in May of 2015, four months after Dick Magney entered the hospital.

While a Humboldt County Superior Court judge denied Judy Magney's request for attorney's fees, he chided the county for withholding the information about Phan and noted the temporary order might not have been issued if those details had been included.

"Given the basic and fundamental rights involved," the judge wrote, the court "would expect the information received from Dr. Phan, a hospital physician caring for Mr. Magney, to be provided to the Court when the temporary order was sought."

When Judy Magney's request for attorney's fees landed before the First District Court of Appeal, it issued a scathing opinion in November, describing the county's actions as "beyond the pale."

The court's panel of three judges also took the step of publishing its decision — something done in only 10 percent of the cases that come before the appellate court — meaning the opinion became citable case law in California.

Calling the county's authority to have even petitioned the court to compel treatment under the state's Health Care Decisions Law "questionable," the panel's opinion outlined why the justices concluded that "Humboldt deliberately misled the trial court and made what could be called a "fraudulent" showing of evidence in the appeal.

Using phrases like "lack of candor," the panel found that Angus — the county's deputy counsel — seemed to have the view "that if Humboldt needed to be duplicitous to get an order compelling treatment, so be it."

"In sum, Humboldt was not merely negligent in preparing its petition and request for an order compelling medical treatment under the Health Care Decisions Law; it knowingly and deliberately misrepresented both the law and the facts to the trial court," the opinion states. "We would find such conduct troubling in any case. In the instant context we find it profoundly disturbing."

The county never took action regarding the allegations that Dick Magney had possibly been neglected, and, the appellate court noted, the county never presented "any competent and admissible evidence" that any neglect had occurred.

The opinion goes on to state that "Humboldt clearly lost sight of the fact that the Health Care Decisions Law does not provide a forum to debate the wisdom of a particular individual's health care choices" and that advance health care "instructions remain operative after a loss of capacity."

"While it may have been Humboldt's view that further medical treatment was in Mr. Magney's 'best interest,' that was not consistent with his instructions or stated personal values — all of which he set forth when he indisputably had capacity to make health care choices and none of which Humboldt ever discussed or directed the trial court's attention to in its removal petition or application for an order compelling treatment," the opinion states.

David Levine, a professor at UC Hastings College of the Law, said the decision shows the panel of judges was clearly "very disappointed in (Angus') conduct throughout the case."

"This opinion contains some harsh language but when a court believes it has been so deliberately misled by an attorney, the written opinion can sometimes be withering," he said. "It is unusual, but not unique."

Based on his reading of the opinion, Levine said he's unsure why the case got to the point it did.

The law professor said Dick Magney's condition — an older man with serious health problems — was exactly the type of situation the Health Care Decisions Law was designed to address: allowing individuals to decide for themselves whether to receive life-prolonging treatment, and for that decision to remain in effect even when they could no longer speak for themselves.

"Everybody here is on board except an outside third party, and they're not even family members," Levine said. "It's a very unusual case. ... An outlier."

He also noted that Angus made numerous "obvious" mistakes in the original proceeding then continued to adhere to them in the appeal. Angus, meanwhile, appears to be under consideration for a Humboldt County Superior Court judgeship based on letters of query sent to local attorneys by the governor's office.

"I would hope that this opinion would get substantial attention in the course of that process," Levine said. "In itself, it may not be disqualifying, but it is certainly disturbing and deserves careful weighing."

When Jackson, Judy Magney's attorney, first received the case back in March of 2015, she thought it was all a simple misunderstanding. A former prosecutor, she had worked with Adult Protective Services in the past and was well acquainted with Angus, a former public defender.

Surely someone would realize what had gone wrong and correct it, Jackson recalled thinking at the time.

That's not what happened, Jackson said. Instead the county would double down, then triple down and now — nearly two years later with the recent request to depublish the appellate opinion — quadruple down while continuing to cite what the court has already disregarded as "appallingly inadequate" and "unsupported factual assertions."

That includes once again raising the never pursued or substantiated allegations of neglect, with County Counsel Jeffrey Blanck going so far as to claim that the county did what it did "to ensure Ms. Magney did not deliberately hasten her husband's, Dick Magney's, death against his express wishes by allowing doctors to withdraw treatment for the life-threatening medical condition created by her neglect" in the county's depublication request.

"They're creating their own universe just to justify their civil rights violation," Jackson said.

The case took a devastating toll on the Magneys, she said, noting at one point the county wouldn't even allow Judy Magney to be told how her husband was and what was going on with his care.

"The emotional costs, I can't begin to calculate, but she didn't give up," Jackson said. "The financial costs. I can't begin to calculate that either, but she didn't give up. She didn't give up because this was her husband."

Dick Magney died in a skilled nursing facility eight months after the county first began efforts to take control over his health care decisions, living long enough to see them denied — at one point testifying in his own conservatorship case that he was angry at the accusations being made against his wife.

He described her as simply "the best," saying, "She's a great cook, and must have the patience of Job to put up with someone like me."

The appellate court's scathing opinion about the county's action came a little over a year after he died having spent his final months in a legal tug of war over his medical decisions and end-of-life wishes.

While the county of Humboldt argued in its letter seeking depublication that the precedent set by the appeals court's opinion would tie the hands of other investigators looking into future cases of abuse, Levine disagreed.

The law professor said the ruling is extremely helpful in laying out the path that should be taken in the event an advance care directive is being challenged, as well as who has the authority to do so.

"Humboldt is really trying to minimize the embarrassment flowing from this opinion," Levine said of the depublication request.

The ruling should, he noted, be used as a primer in training abuse investigators as a "cautionary tale" that says: "Don't let this happen to you. Follow these steps."

Noting the difficult job involved in investigating abuse cases, Levine said there needs to be an acknowledgement that sometimes mistakes are made. According to the county, Adult Protective Services received more than 1,000 reports of suspected abuse that had to be investigated between July of 2015 and June of 2016.

That being said, Levine noted, there are questions to be raised about the way the Magneys' case was handled and why the county is continuing to "double down" on its position.

"The nature of investigating abuse cases is you're going to have to separate out the wheat from the chaff," he said. "What is it about the personalities that kept this one going?"

Jackson said what needs to happen is simple: The county needs to acknowledge what happened, apologize and settle with Judy Magney; the supervisors at APS need to take a hard look at what occurred with their agency; and the Board of Supervisors needs to question the actions of its county counsel office.

"The clock," she said, "is ticking."

For her part, Judy Magney said she is in a much better place than she was a year ago. If the case helps prevent someone else from enduring what happened to her and her husband, "that would be great."

Right now she's clearing out the country property where she and Dick started their new life together all those years ago. It helps, she said, to stay busy.

"I don't want to stay in Carlotta anymore," she said, "now that he's not there."

Editor's note: To read attorney filings in the case and the appellate court's decision, click on the hyperlinks in the story.Speaking of...

-

Repairs to Grandstands Ready By Humboldt County Fair Time

Aug 21, 2023 -

Supes Decide Not to Censure Bushnell

Nov 1, 2022 -

Supes to Consider Bushnell Censure

Oct 31, 2022 - More »

Comments (12)

Showing 1-12 of 12

more from the author

-

Dust to Dust

The green burial movement looks to set down roots in Humboldt County

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Our Last Best Chance

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Judge Rules Arcata Can't Put Earth Flag on Top

- Apr 5, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023