Liquor Run

After an earthquake shakes Humboldt, the Harbor District continues its push to avert looming disaster

By Grant Scott-Goforth [email protected] @GScottGoforth[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

When the undulations of the March 9 earthquake rousted Jack Crider from his sleep, his first thoughts were the Samoa pulp mill; specifically, the nearly 3 million gallons of caustic fluids poised to spill out of old, failing storage tanks and into Humboldt Bay.

Those liquors — remnants of the pulp mill's production days — have been a threat to the bay for years, and even a gentle rolling earthquake like that one was enough to motivate Crider, CEO of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District, to put on his shoes, grab a flashlight and head down to the mill to look for leaks. He was the only one poking around the old tanks that night, but half a dozen concerned community members called him the next morning. People are worried about those liquors.

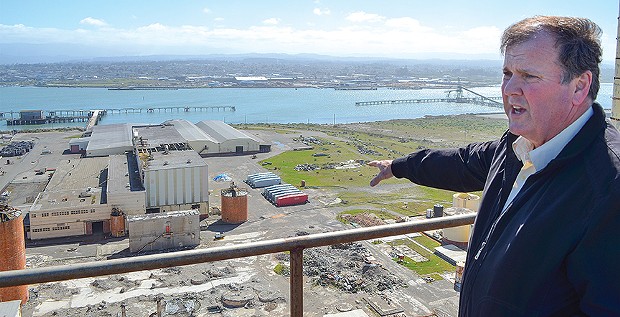

A couple weeks later, Crider stands on a tarpaper surface 200 feet above the sands of the Samoa Peninsula, beaming at the structures and piles of rubble below as gusts of cold ocean air ruffle his hair.

He paces across the broad, flat roof of the Samoa pulp mill's boiler, the hulking monolith unused since 2008 that once spewed stinky white steam into the air above Humboldt Bay. From the dizzying height of the county's tallest building, Crider excitedly points out the improvements and potential of the 72-acre mill site that his agency acquired in August.

In that short time, the harbor district has gotten rid of and secured hazardous chemicals around the old mill. And a steady stream of trucks is scheduled to soon begin hauling the remaining pulping liquors — millions of gallons of ultra-basic chemicals — up to Washington, where they will be reused.

Crider and the harbor district aren't the only ones relieved to see the liquors going — The Environmental Protection Agency and local oyster farmers are thrilled, too. And you should be, if you recreate on the bay, enjoy local shellfish or benefit from Humboldt County's economy. Those chemicals, housed for the last six years in failing and nearly overflowing tanks, have been threatening the economy and health of Humboldt Bay, with every tremor or rainstorm increasing the danger.

But safety is nearly here, as well as a new life for the Humboldt Bay property.

When the harbor district acquired the pulp mill after a year of negotiations, the district board and staff knew they were in for a large project.

Concerned about the security of the estimated 4 million gallons of pulping liquors, the caustic fluid used to turn wood into pulp, the district asked EPA coordinator Steve Calanog to inspect the site.

"I was out there earlier doing some work on Indian Island and the harbor district acquired the pulp mill and asked me to come over and take a look," Calanog said. "I determined there was quite a bit of hazardous material and began to initiate an emergency response."

By that point the tanks were nearly overflowing as years of rainwater had accumulated in them. But quick action was no guarantee — the federal sequester was about to begin.

"That was a time of real political turmoil," said North Coast Congressman Jared Huffman. "When the concern about leakage arose it was at the worst possible time — it was right as we were heading into a government shutdown."

Huffman said he and his staff pressed for federal funding on the site, "but to EPA's credit they responded immediately — they understood what was at stake here."

The uncertainties didn't end there. EPA began searching for a barge company that could transport the liquors — 3 million gallons, after some measurements — and a pulp mill that would accept them. One solution came from Capstone Paper in Longview, Wash., a town of about 36,000 on the Columbia River. The company will boil the liquors down and reuse them. No money will change hands over the liquors, Calanog said.

But shipping the liquors has been frustrating for the agencies and will be costly. Anticipating that the liquors would be shipped by barge, the harbor district rebuilt its dock, brought in temporary tanks and laid down a large network of large black pipes. But the barge fell through. Longview's port demanded $800,000 worth of improvements in order to offload liquors there and coast guard-approved chemical barges are scarce on the West Coast, Crider said.

The EPA is still searching for a barge, but will begin shipping the liquors via truck by the beginning of April. The first 200 shipments are already scheduled — trucks will haul the liquors, about 2,500 gallons at a time up U.S. Highway 101 to Crescent City, along the twisting U.S. Highway 199 over the pristine Smith River to Grants Pass and up Interstate 5 to Longview.

"There's additional risk with trucks, especially that many," Crider said, but it has to be done. "We're just on borrowed time."

The hauling will be just another drop in the stream of around 2,000 trucks that come in and out of Humboldt County daily, Crider said. Whether logs, gasoline or pulping liquors, there's always potential for an accident. Crider said both the harbor district and the hauling company have insurance in case of a spill. Trucking the entire liquors supply to Longview will cost $1.6 million, Crider said.

Peering over the dock as a crew worked on oyster equipment below, Taylor Mariculture Operations Manager Mitch White said getting the liquors away from Humboldt Bay is crucial. The oyster company is investing millions of dollars into the dock and warehouse facilities at the pulp mill — investments that could be ruined by a leak. White's anxious for the cleanup. "The sooner the better — for everybody," he said.

If the tanks failed, the liquors would flow into the bay, Calanog explained, dramatically changing the pH and disrupting oyster production and the bay's fragile ecosystem. And the longer the liquors sit on the peninsula, the greater the risk. "There's no telling how long it would take the bay to recover," he said. "It would both be an environmental and economic disaster up there."

As Calanog knows, a spill could prove catastrophic for one of the area's emerging industries.

Though aquaculture remains a relatively small percentage of Humboldt County's recorded economy, the county listed "fisheries, processing and aquaculture" as one of its nine industries to promote as part of its prosperity strategy. A 2010 survey reported that Humboldt Bay shellfish production totaled $9.3 million in sales, half of the bay's total seafood value that year. Aquaculture made up 30 percent of the North Coast's total $31.4 million in seafood landings, according to the survey.

Although the March 9 earthquake, a strangely mild 6.8, caused no damage, it increased the harbor district's urgency, Crider said.

Perched above the pulp mill grounds, Crider points out that there's a lot of work still to be done. Once the liquors are shipped away, the EPA's superfund people will remove the sludge and solids and dismantle the liquors tanks. The Harbor District also secured EPA brownfield funding to clean up less hazardous materials around the mill.

After Evergreen Pulp's quick departure in 2009, the company sought to recoup costs by selling off valuable copper wire, piping, steel and other reusable materials that made up much of the water, sewer and electrical infrastructure of the mill. Still, valuable assets remain on the property, and Crider is confident they will attract businesses who will invest in and lease space from the district.

Looking west, Crider pointed to a mile-and-a-half pipeline into the Pacific, which could eventually discharge the entire peninsula's wastewater. Below the boiler building sits an electrical substation and the site's natural gas pipeline — two important incentives for businesses, Crider said.

To the east sit the mill's massive warehouse space, dozens of offices, the mill's operational generator and the dock. Still-functioning cranes dot the pulp mill's landscape. Taylor Mariculture has already built "flupsies," large nursery rafts used to culture oysters in the bay. The accessibility of the dock will make for convenient "show and tell" opportunities for Taylor and others in the oyster industry, Crider said.

Even the dormant giant under Crider's feet, the boiler that once cooked organics off of the liquors so they could be reused, may be valuable to the district. Crider said the agency is negotiating with a pulp mill in the Philippines to sell the boiler. He expects the district can get around $2 million for it, money that would be used to help pay for the cleanup.

Final plans for the pulp mill are evolving, and depend on the businesses that will eventually land there. Potential uses dreamed up by the district include export of lumber and other goods, aquaculture and research, food and industrial manufacturing and a public dock. Crider thinks the district will have enough interested businesses that the most difficult part will be deciding what kind of uses are best for the mill site — and Humboldt County.

For more than 40 years, the mill site has lurked as one of the area's most prominent landmarks. Crider visited Eureka as a fish buyer in the mid-'90s and distinctly remembers the odorous mill's effect on the city. Enamored with the area, he recalled thinking, "It really sucks about the pulp mill."

In the years to come, the boxy, sooty boiler building, one of the most recognizable parts of the Humboldt Bay skyline in combination with the 300-foot-tall crimson-topped smokestack, may be gone for good.

Pulp Mill Timeline

1964 — The pulp mill is built by Georgia-Pacific on the Samoa Peninsula.

1965 — The mill begins operation.

1989 — Environmental groups sue Louisiana-Pacific, which now runs the mill, and the Simpson Paper Company, which runs another mill nearby, alleging the mills are daily discharging tens of millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into the ocean. According to the suit, scientists found traces of a host of toxic chemical byproducts of the chlorine bleaching process, including dioxin and furan, in fish and crab samples from near the discharge sites.

1991 — The companies settle the suit, agreeing to pay a combined $5.8 million in penalties to the Environmental Protection Agency. Following the settlement, Simpson shutters its mill and Louisiana-Pacific converts its mill to a chlorine-free production process. In the ensuing years, Louisiana-Pacific sells the mill to a group of investors, which then re-sell the mill several times, with it ultimately landing in the hands of Stockton Pacific.

2005 — The Chinese-owned Lee and Man Paper Co. purchases the pulp mill under the name of a subsidiary, Evergreen Pulp.

2006 — Environmental groups again sue the mill's owners, this time alleging significant and ongoing violations of the mills federal air quality permit.

2007 — Evergreen settles the suit by agreeing to install a $1 million, state-of-the-art emissions control system.

2008 — Lee and Man Paper Co. sells Evergreen Pulp to a new investment group as the mill announces a temporary closure with plans to re-open in three to six months. During its ownership of the mill, Evergreen pours more than $40 million into improving the facility and remains profitable. However, in 2008, the pulp market goes into steep decline and Evergreen falls delinquent on its bills, with some suppliers and contractors acquiring court liens.

2009 — With Evergreen Pulp totally insolvent, Freshwater Pulp Co., led by Bob Simpson, purchases the mill with plans to get it up and running again.

2010 — Simpson announces he is unable to secure some $400 million in financing needed to re-open the mill and that it will be permanently closed.

2013 — The Humboldt County Harbor, Conservation and Recreation District acquires the mill site from Simpson at no cost, knowing there are some 4 million gallons of caustic pulping liquors on site that need to be removed. Within months, the district has the federal Environmental Protection Agency inspect the site and it is immediately federalized as the EPA initiates an emergency response to secure the pulping liquors and plan for their removal.

2014 — The EPA and the district plan to begin trucking the liquors off site beginning in late March.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

more from the author

-

Flamin' Hot's Stale Corporate Propaganda

- Jun 15, 2023

-

Hell is Visiting Other People

- Sep 22, 2022

-

The Bear Roars

- Aug 18, 2022

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023