Fixing the World

If the condor comes back to Yurok country, maybe the country will come back for everyone

By Heidi Walters[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

A couple of hours past noon the turkey vulture rode a current from the northwest into the blue space above the Bald Hills, east of Orick. It soared, black-and-gray wings fixed in a teetery V, up over a grass-yellow pointy hill topped with trees and out over a broad ridgetop prairie dense with tall grass, dandelions and low tufts of dark brackenfern. The past few days, there'd been food down there: dead bear. The smell had been enough to draw the keen-nosed bird in, and the black furry heap a confirmation.

Another turkey vulture soared over the horizon into the blue above the hills, and another and another. A meadowlark trilled, liquid, from somewhere deep in the grass where the flattish ridgetop began to slope down toward more sets of rolling grass hills mingled with oak woodland.

There was a whiff of something. But instead of circling down to investigate, the vultures stayed high, made a few distant tilting sweeps, and sailed on. People were down there today.

Tiana Williams saw the vulture soar into view and pointed it out to Chris West. When the other vultures came in and swirled briefly above the close hills, Williams and West revived their latest running joke: that the turkey vultures know them.

"We leave carcasses everywhere," West said. "And turkey vultures can't open up carcasses. A condor can. But the turkey vulture's beak isn't strong enough. And here we go out to seal and sea lion carcasses and open 'em up. And the turkey vultures go, ‘Oh great! The people with the knives showed up!'"

They'd not only been knifing open dead marine mammals down on the beaches. West and Williams also had been leaving fresh carrion on this flat ridgetop. But today there was just a small remnant of a black bear they'd left days ago -- a shaggy leg with clawed paw still attached and in the flattened grass nearby a dried twist of something, maybe entrail. The bear carcass had been donated to West and Williams from a dissection lab at Humboldt State University.

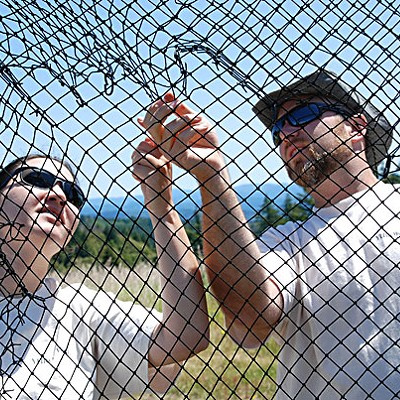

Now they were slowly erecting a net-draped rectangular cube around the bear scraps: four panels made of PVC pipe, each wrapped in strong black netting secured by hooks, clamped together and covered with an airy roof made of wood and wire. Part of the roof was ladderlike with rungs upon which, say, a turkey vulture could perch before dropping between rungs to feast on the carcass within, but through which it would be unable to lunge back out. West designed the contraption, modeling it after one he'd used belonging to U.C. Davis researchers. His is lighter and can be assembled on the spot, making transport into the backcountry easier. And, yes, the trap is intended for turkey vultures -- several could gather in it at once.

Williams and West are the sole employees of the Yurok Tribe's fledgling wildlife program. West, a 38-year-old condor biologist, was hired by the tribe to head the program. Williams, a 23-year-old Yurok Tribe member, graduated from Harvard a couple of years ago with a biochemistry degree and an itch to get into wildlife management. Their first project is to explore what it would take to reintroduce the California condor to Yurok ancestral territory.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service awarded the tribe a $200,000 grant to do the feasibility study, and the tribe is working with many other collaborators, including Redwood National and State Parks, several universities, Six Rivers National Forest, the U.S. Geological Survey, condor breeding programs in California and Oregon, and private landowners.

But it was the Yuroks' idea.

"It's written in the Yurok constitution, and it's always been one of our goals, to have restoration of Yurok ancestral territory -- the landscape, the animals -- to what it was pre-contact with Europeans," said Williams.

Toward that end, the tribe is nearing closure on a deal to buy 47,000 acres from Green Diamond Resources Co. Right now, the tribe's reservation is but a two-mile-wide ribbon of land, through which the Klamath River flows, that descends from Weitchpec down to the ocean.

A few years back, said Williams, some elders were discussing what creature they wanted the wildlife program to restore first once they had more land. Some said, let's do the salmon -- but another department was already taking care of salmon. Someone else said sturgeon -- but, same story as the salmon. And then someone -- Williams doesn't know who -- said, how about the condor?

It made sense. Cathartidae -- the taxonomic family the condor, like the smaller turkey vulture, belongs to -- means purifier. Vultures clean the world. And the condor is the biggest vulture.

Gymnogyps californianus nearly went extinct. In 1987, when the last wild California condor was brought into captivity, there were just 22 of them left in the world, all in California, all now captive. A controversial, laborious captive breeding program over the ensuing 20 years coaxed the California condor slowly out of the ghostland. As of this June, there were 358 in existence, 189 of them living in the wild, including some wild-hatched chicks. About half the wild ones live in California, the rest in the Grand Canyon region and in Baja Mexico.

Williams and West have to find out if the things that pushed the California condor over the edge, and still pose a threat today, are in high concentrations in this region: lead bullets and DDT, but also other toxins, like mercury. First, they're collecting the blubber of marine mammals -- potential condor food -- to measure exposure to DDT.

"DDT binds to fat, so we don't get that much of a problem with fish because they're just not that fat," said West, who has worked with the condor reintroduction program in Big Sur since 1999. "But animals that are long-lived, like pinnipeds, that have a lot of blubber on them -- it just accumulates over the lifetime of that animal. In Big Sur, recently, they found that condors that were feeding on pinnipeds were getting high levels of DDE, which is a breakdown product of DDT. There was a lot of late-stage egg mortality -- the chicks died of dehydration from increased water loss through the thinned eggshells. It was similar to what happened in the '70s during the height of DDT."

West said California condors nesting in Southern California far from the coast didn't have DDT-compromised eggs. The historic record indicates that North Coast-dwelling condors in the past feasted regularly on marine mammals. But West said maybe our resident mammals, at least, like California harbor seals, won't have been exposed to DDT spills in southern California, and to current use of DDT in countries south of the U.S. border. However, the sea lions that migrate through here might show exposure.

They're also catching vultures in the region.

"Condors and turkey vultures eat the same things, so we can use turkey vultures as a ‘sentinel' species," said West, adding that turkey vultures can survive lead exposure much better than condors can. "But they do absorb it. So we can observe exposure trends in them."

At the Bald Hills site, they've been putting out fresh bait to gain the vultures' attention. Now they're pre-trapping -- luring the birds into the trap, but with the net walls rolled up so they can escape. Once the birds are used to the trap, it'll be baited again and someone hiding in a nearby copse will pull a string and lower the net the next time the birds drop in. (The traps will be opened at night so other animals won't get stuck in them.) Once caught, each bird will be measured and tagged with an ID number, have its blood drawn, then be let go. The blood will be tested for lead and mercury, and possibly DDT.

One problem: Turkey vultures do migrate. They arrive on the North Coast in May, and they leave in August just as hunting season is starting up. But condors, if reintroduced here, would remain during hunting season. So West and Williams are also trapping ravens, who live here year-round, to fill in the picture. Although, said West, the omnivorous ravens aren't the purest of sentinels.

"They'll eat cheese puffs at a campground," he said.

Although the condor eked out a desperate living up until the 1980s in southern California, the last condor to soar over our particular hills may very well have been the poor fellow now ensconced behind glass at the Clarke Historical Museum in Eureka. It was shot sometime in the 1890s up in Kneeland.

But the California condor likely ranged widely across North America in prehistoric times. After the mass extinctions of large vertebrates 10,000 years ago, the California condor retreated to the West Coast. Some scientists think a few condors lingered around the Grand Canyon area, also, and maybe in some other inland states.

The California condor appears in a lot of tribal cultures. Helene Rouvier, of the Wiyot Tribe, says condor feathers are part of the traditional doctoring regalia, much of which, however, was lost to pilferers but which they're trying to regain.

The Yurok word for the condor is prey-go-neesh. They say there is a place on the Klamath River called "Condor where he sits." Yurok Bob McConnell says condor feathers traditionally were used in the Jump Dance and White Deer Skin Dance, both part of the tribe's late-summer world renewal ceremony -- which, said McConnell, a deer skin dancer, is intended to restore the world for everyone, not just the Yurok. But for a long time the tribe hasn't had fresh condor feathers to use. Like the Wiyot's, much of its regalia were taken away to museums. And although some have been returned, they're contaminated with toxic preservatives.

"We bring those feathers back, and those feathers are taken to the ceremony," said McConnell by phone a couple weeks ago. "And they get to watch the ceremonies, because we believe there is a spirit associated with each feather in the regalia. But they don't get to participate. So there's kind of an unfulfilled capacity."

With the return of the condor, and new, uncontaminated feathers, those spirits could participate again -- although the tribe wouldn't kill the birds to get the feathers, said McConnell.

Richard Myers, a Yurok tribal council member, is one of the Jump Dance participants who sing and fast for 10 days. By phone a couple weeks ago, Myers recounted how surprised he was 20 years ago when the tribe was reviving its ceremonies and an elder from Pecwan sang a condor song.

"It was the first time any of us had ever heard it," Myers said. "We didn't know there was a condor song. And we thought, what happened to the condor?"

Someone gave Myers fresh condor feathers four years ago, and he saw his first condor a couple years ago at Pinnacles National Monument, a condor release site. The elder who sang the condor song has passed on, but now one of his grandsons sings it. So pieces of the bird are slowly coming back.

Every piece is important, said McConnell. "In today's world, humans see almost everything as subordinate to themselves," he said. "And in the past, we Yurok didn't see ourselves as that. We saw ourselves as one piece of this greater picture. And our duty was to conduct ceremonies, and pray for balance, and pray for good things to happen like a good harvest of food, whether it be acorn or salmon or deer. But a lot of that has been lost.

"We as Yurok are looking to restore our culture, and to restore our culture we need to have a healthy ecosystem. And to have a healthy ecosystem you've got to have all the participants, and the condor certainly was one. He's one of the big missing pieces."

Condors, as carrion-eaters, have to check out everything. Which often puts them in harm's way. European settlers shot at them, thinking erroneously the birds could carry off children and pets. Or the birds died after eating strychnine-laced meat intended for wolves or other predators -- or after eating the poisoned predators themselves. Some Gold Rush miners used condor feathers, for which the birds were killed, to store gold dust. Museum collectors killed some condors. Then DDT, lead shot and even overhead wires practically finished them off.

Today, lead poisoning may be the biggest threat to California condors. When an animal is shot, the impact scatters lead throughout the animal. Condors will ingest the lead-ridden gut piles left behind, or the remains of an animal that was shot but got away then died. Since 1992, says the Center for Biological Diversity, at least 15 condors have died in California from exposure to lead, while dozens of others required de-leading treatment.

A movement to ban the use of lead in hunting and even fishing is gaining momentum. The 2007 Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act banned hunting of big game like deer and elk, as well as coyotes, with lead ammunition where condors currently range in California. The California Fish and Game Commission wants to extend the ban to the hunting of small game like rabbits and birds. And the National Park Service announced this spring that it has banned its staff from using lead ammunition to cull wounded or sick animals, and said it hopes to ban all use of lead bullets and fishing tackle by the end of next year.

The National Rifle Association isn't pleased. But not all hunters are opposed to a lead ban. A recent call to a local hunter hangout, Bucksport in Eureka, caught Reed Gatton working his part-time shift. He said he's observed that about half the hunters he talks to who come through the shop are worried about a lead ban. But the other half thinks it's worth a try.

"Personally, I think it's not a bad idea to not use lead," Gatton said. "But the biggest problem is a lot of people have ammo stacked up. For myself, I've stocked up 200 rounds. And I only shoot 20 rounds a year."

Plus, the alternatives -- bullets made of copper, or alloys of other metals -- can cost twice as much as lead bullets. But they work really well, said Gatton. And with time, their price would come down if they became the standard.

Tiana Williams, who hunts, said she will switch to non-lead bullets this year. And she and West think a voluntary switch to non-lead ammo would work better than a ban in this region. She said a switch would benefit not only future condors, but people as well.

"The tribe does a lot of subsistence hunting, and because the shot scatters in the animal on impact, my people are eating lead too," she said.

Up in the Bald Hills in a grassy saddle between hilltops, a herd of elk grazed. The surrounding sweep of hill and forest revealed little sign of humans: a few twisty dirt tracks; an old barn; the fortress-like fire lookout on School House Peak. There were a few hilltop snags where a large bird could perch to survey the broad landscape or just soak up the last light of evening or the first light of morning. A cold wind blew in, steady as ever, from the ocean -- a condor could easily open its 10-foot spread of wing into that wind, lift its great bulk into the air, and soar on one wingbeat for 60 miles or more. In an hour, it could be at the coast ripping open dead sea lions and gorging. Or in some valley eating a downed elk. Or back to the redwood tree cavity -- or perhaps that place in the cliff on the Lost Coast -- where it had laid its egg.

A robin chortled. The meadowlark trilled once, twice. Movie-style, a redtail hawk swept overhead and let loose a sky-curdling cry. Then a turkey vulture rode silently in on a northwest current into the blue space above. And here came another, soaring in over the yellow-grass horizon. And another.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Lincoln's Hearse

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023