Champions of the Rodeo

While segregation was still the law of the land, two black men helped break rodeo's color barrier in Fortuna

By Susan J. P. O'Hara and Alex Service[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

On March 27, 1912, the Fortuna Advance newspaper ran an article headlined, "Black Man Rides White Man Thrown." The Advance reported that a "bronco busting exhibition given by Jeff Stall the colored dare-devil from Ferndale" took place March 24 "at the old fairgrounds in Rohnerville." More than 200 people attended and "in return for the two-bits gate money were given a two-hour exhibition of riding outlaw horses by the colored man." According to the Advance, the dare-devil rode four horses to a standstill before leaving Rohnerville for Fort Seward and Dyerville "in search of other outlaw horses, which ... he will attempt to ride at a date and place to be announced."

Despite getting Jesse Stahl's name wrong, the Fortuna Advance article chronicles the first chapter in the career of a man who would go on to become one of the most celebrated figures of early rodeo history. A few months after he rode those four horses to a standstill in Rohnerville, Stahl would burst onto the scene with a ride in Salinas that is now part of rodeo legend. In 1979, more than 40 years after Stahl died penniless and alone, he was posthumously inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame — becoming just the second African American to receive the honor.

Humboldt County's rich ranching heritage and history are celebrated each year at the Fortuna Rodeo, which kicked off this week, as well as others held throughout the North Coast. The Fortuna Rodeo is the region's oldest, having started in 1921 as entertainment for the Humboldt Stockmen's Association. Many cowboys and animals featured in the first rodeos held in Humboldt came from area ranches. Local men and women have competed in Fortuna and other Humboldt rodeos, stock gatherings and riding exhibitions since the 1850s, some going on to great fame. Among them were two African-American cowboys who became rodeo legends in the 1910s and 1920s: Stahl and Ty Stokes.

The lives of Stahl and Stokes illustrate the experiences of black cowboys who worked on cattle drives and ranches in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Historians estimate that one of every six cowboys was African American, many traveling west after the Civil War. These men encountered numerous prejudices on the frontier and were often given the hardest jobs involving taming rough stock. This work provided the training ground for black rodeo performers, perhaps including Stahl and Stokes. The incredible abilities of Stahl and Stokes led them to be recognized for their skills, allowing them to rise above some of the discriminations of an era of blatant and violent racism. Jim Crow laws were prominent in the south but the south had no monopoly on racism and discrimination. For instance, in a tourism publication dated 1937, Humboldt County proudly advertised itself as the only county in all of California with no Chinese residents. During this period, far less than 1 percent of Humboldt's population was comprised of African Americans, according to Census records. The 1910 Census showed 23 African Americans living in Humboldt County, a number that had only risen to 53 a decade later.

Stahl and Stokes encountered racism on the rodeo circuit. They were often ranked lower than they deserved and ultimately turned to exhibition riding. Newspaper accounts and other sources cited in this article include disparaging and prejudiced comments, and offensive nomenclature, but are included to reflect the environment in which the two men worked and the discrimination they faced.

The older of the two, Stahl, was born in 1884. His birthplace is listed in different accounts as Tennessee, Texas, or California, perhaps in Humboldt County. One story has him coming to Humboldt as a cowhand with a herd of cattle from Oregon on its way to a ranch near Petrolia. At the ranch Stahl was challenged to a riding contest and ultimately defeated every competitor. Stahl is also known to have worked as a street sweeper in Ferndale and in 1912 he is listed in the Ferndale directory as a horse trainer.

Stahl's World War I draft registration lists him living at 1212 F St. in Eureka, self-employed in the "garbage business." His birthday is listed as July 7, 1884, and he reported being 34 years of age in 1918, with his height and build recorded as "medium." A paper by Humboldt State University student Dennis O'Reilly titled "The Black Experience in Humboldt County 1850 - 1972," written for Dr. Hyman Palais' history class in 1971, notes Stahl and Stokes spent the offseason from the rodeo circuit in Eureka during their careers. Oral history collected by O'Reilly recalls Stahl living in Eureka during WWI, racing his horse and practicing trick riding in alleyways behind his home.

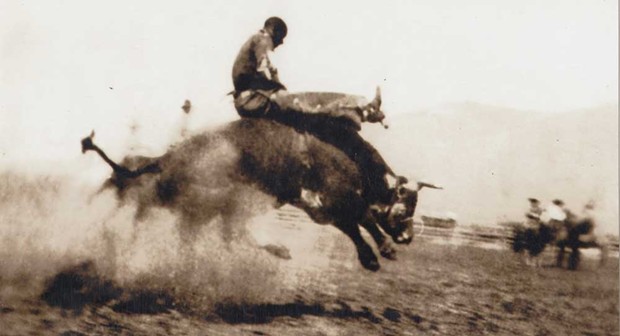

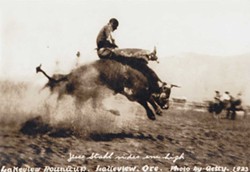

Four months after his exhibition ride at the Rohnerville fairground, Stahl rode in the Salinas Rodeo and became part of rodeo history when his riding of "Glass-Eye," a bronc that had never been ridden, brought him instant fame. A photograph of Stahl on Glass-Eye depicts the horse on one leg and Stahl grinning as he completes his ride. Another cowboy of the period observed Stahl was very strong and could pull a horse's head back so that it would not, or could not, buck him off. At that time, saddle bronc riding had only two rules: The rider had to hold the reins in one hand, the other hand not touching the horse, and the rider who stayed on the longest won, with the ride continuing until the horse stopped or the rider was thrown. Modern rules require the rider to stay on the horse for only eight seconds.

Regrettably, Stahl's outstanding ride on Glass-Eye was judged third place, falling into a pattern in which Stahl's performances received less official recognition than deserved, the likely result of prejudices of the era and all-white judging panels. Many black cowboys experienced similar discrimination during this time. White cowboys would often refuse to compete against black men. But Stahl's answer to biased judges and riders was to prove his skills in exhibition rides. After being scored second at a rodeo in Klamath Falls, he came out of the chutes backward on a bareback bronc, holding a suitcase. He also perfected a well-known routine in which he rode a bronc with another man, frequently Stokes, with one facing forward, the other backward.

Stahl performed at rodeos throughout the 1910s and 1920s, traveling from California to Canada and New York. In 1919 the San Francisco Chronicle, under the headline "Black Bronco Buster Going After Big Prize," observed "Jesse Stahl, a bronco buster from Salinas, as black as tar and with a smile that spreads to his ears left here last night for Calgary, Canada, to horn in on the $25,000 cash prizes put up for rough riding, bulldogging steers and such like. And Jesse intends to bring back some of that dough. He says he can ride anything that wears hair and is not afraid to tackle bald-faced horses." Cowboys, like athletes, have their own superstitions and white faced, or "bald faced," horses were thought to be bad luck or hard to ride.

The article also notes Stahl "went to New York in 1916 and won the bulldogging event and also took first in the barebacked riding. His specialty is riding barebacked with his back turned to the horse's head. He challenges the world in that style of riding." In 1920 the San Francisco Chronicle included a photograph of Stahl with the caption he "is as much at home on the back of a steer as on a bucking bronco," in reporting about the Salinas Rodeo. The Oregon Daily Journal that year, reporting on the Pendleton Round-up, observed Stahl was "the only colored bulldogger ever seen here," noting he was "prepared to battle again for the title."

Stahl was also renowned for creating a rodeo event called "hoolihanding," similar to bulldogging, which was created by African-American cowboy legend Bill Pickett. In bulldogging, a rider jumps from the back of horse on to a young bull, twisting the neck, until the animal is flat on its back. Pickett was known to bite the nose of the animal to encourage it to fall. In hoolihanding, the rider jumps from a horse onto the back of a full grown bull. Once aboard, the cowboy grabs the horns, riding the bull until it is tethered by its horns. Hoolihanding was canceled as an event after a bull broke its neck at a rodeo in California and the sport was deemed too harmful to the animals. Hoolihanding and bulldogging have both been replaced with steer wrestling, as steers' necks are not as strong as bulls', making them easier to flip.

Stahl traveled frequently in the 1920s. In October of 1920, reported the San Francisco Chronicle, Stahl, "the well known colored bronco buster and cowboy rider, a prominent figure wherever rodeos are held," had "reached San Francisco last night from the Pacific Northwest and left for Oklahoma City, where he is under contract to appear. Stahl has just finished with exhibitions at Bozeman, (Montana); Boise and Weiser, Idaho and Pendleton, (Oregon)." Rodeo organizers would hire Stahl as an exhibition rider, which allowed him to avoid judges' and other cowboys' prejudices while providing needed income. In July of 1921, the Reno Gazette-Journal observed "Stahl gave a wonderful exhibition of riding. The bronc he was on tried every way to throw him and finally rolled Jesse, but the game colored boy held fast and had his horse 'dead.' He was dragged from under him. Stahl was not hurt and came back and won the bull dogging and wild horse race."

Perhaps the greatest accolade given to Stahl is that the newspapers changed from mentioning the color of his skin to highlighting his abilities, endurance and athleticism. In 1925, Stahl competed at the Klamath Falls Rodeo, 10 days after a steer he threw at the Prineville Rodeo gouged a finger off his right hand. Throughout the article, the Klamath News never mentioned he was African American, instead focusing on his skills riding the horse "Hot Dam." The paper quoted Stahl as saying, "Folks, them rodeo radiators shore (sic) is hot to sit on" and noted that the public was "entirely unaware of his painful physical condition." The article commends Stahl, noting he "put up one of the most sterling riding exhibitions of the rodeo." In 1928, after almost two decades on the rodeo circuit, Stahl's performance at the Hayward Rodeo was hailed by the Hayward Semi-Weekly Review as "the outstanding feature of the riding events."

Then 44, Stahl easily outdistanced modern bull riders who retire by age 30, having at most a 10-year career, half the length of Stahl's. In 1965, Sam Howe, a cowboy contemporary of Stahl's, described him as the greatest bull rider he had competed with in an article in the Petaluma Argus-Courier. Another account, from Texas cowboy Henry Howe, also reported in the Argus-Courier tells of a time when Stahl was in a bar in Texas with other cowboys when Ku Klux Klan members appeared, saying, "'If you don't want a fight, hand us that negro cowboy.' As Howe put it, cowboys in those days never ran from a fight, and instead of handing over Jesse Stahl, they beat the daylights out of the Klan members."

Stahl's last year on the rodeo circuit came in 1929 and one of his last rides was at the Fortuna Redwood Rodeo, where he participated in the professional bucking competition, drawing "Pancho Villa" for one ride and "Prohibition" for the other. It was not his best performance and he scored second to last in both rides. It may have been a particularly painful experience for him because Stokes, his longtime friend and a regular at the Fortuna Rodeo, had passed away earlier that year.

For the next six years little is known about Stahl but the Great Depression was a difficult time for many. In April of 1935, the Woodland Daily Democrat reported "a few months ago [Stahl] disappeared and early this week he was found all alone in a Yolo County shack on the Sacramento River. He died at the hospital." Word of Stahl's death made its way around the rodeo circuit.

The Woodland Daily Democrat noted "the world of the rodeo was in mourning today for the news had been flashed to cowhands in Arizona and crowned heads in Europe that one of the most famous figures of bygone years had died, penniless and alone in a Sacramento County hospital." After describing Stahl's abilities, the paper observed "when his wooly thatch turned gray and his joints stiffened, Stahl could no longer sit on his leaping mounts, but even at the age of 60 he could ride a bucking steer bareback and backwards, and to the end he could pass the dice with the best of them." The Daily Democrat overestimated Stahl's age by a decade. He was a few months shy of his 51st birthday at the time of his death.

Stahl was mourned at rodeo events throughout that year and the May 1935 monthly bulletin of the Rodeo Association of America was dedicated to his memory. The dedication, reported the Ukiah Republican Press, "read, 'This bulletin is dedicated to the memory of Jesse Stahl, the colored cowboy who was well known and well liked by everyone who knew him. He . . . was buried through the co-operation of friends." Stahl was also honored during the broadcast of the Mother Lode Rodeo in Sonora in May of 1935. At the end of the broadcast, "a 30-second period of silence will be imposed in tribute," reported the Oakland Tribune, "after this mourning period . . . his favorite melody, 'Home on the Range,' will be played and sung by the Tuolumne Hill Billies." Stahl's greatest recognition came in 1979, when he was posthumously admitted to the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City, becoming just the second African American to receive the honor, following Pickett, who was admitted in 1971. Stahl's achievements during a time of aggressive and obvious discrimination are substantial, and his athleticism and abilities have continued to be recognized over the more than a century that has passed since he rode those four horses to a standstill in Rohnerville in 1912.

Stokes' grave marker indicates he was born in 1888, four years after Stahl, who would eventually become his friend and competitor. According to his obituary in the Hayward Review, he was born in Kentucky to parents who had been born into slavery. By 1912 Stokes made his way to California, performing at the Wild West Show in Salinas. In 1919, the Oakland Tribune noted Stokes had worked for the 101 Ranch of Oklahoma. Most likely Stokes worked for the ranch owners' Wild West Show, as it was touring in California in the early 1900s. The show would have provided many opportunities for Stokes to learn the skills of trick riding, roping and clowning from fellow performers Tom Mix, Pickett and Will Rogers.

In 1916, the Oakland Tribune reported Stokes lived in Alameda and performed as a trick rider in the San Jose Rodeo. The paper noted "No circus rider ever outclassed Rose Walker of Salinas in the trick and fancy riding event, although Ty Stokes of Alameda was a close second in the opinion of the judges. He received a major part of the crowd's applause." The following year, Stokes won the wild mule race and wild horse race at the same rodeo, placing second in the Trick and Fancy Riding event. During the off-season that year, according to his WWI draft card, he worked for the Black Beauty Horse Show on the Pier at Venice Beach, Los Angeles. Stokes also injured an eye and a hand while riding for the show, making him ineligible for the draft.

From 1918 to 1928 Stokes continued to compete in bull riding and bronc riding on the rodeo circuit in the Pacific Northwest. The San Francisco Chronicle reported, under the sub-heading, "Colored Boy Amuses" that "there is a colored boy down here doing clown stuff. His name is Ty Stokes, and he uses a pair of comedy mules to help him ... for a brief spell this afternoon [he] started a little fancy riding on his own hook ... when Stokes had exhausted his repertoire, a whole lot of white boys had been treated to a riding lesson." In 1975 the Petaluma Argus-Courier described some of Stokes' repertoire, reporting that "Old, old-timers will remember Ty. Ty was also known as a trick and fancy rider ... Ty would leap from a galloping horse to the ground and then vault over the horse to the ground on the other side without touching the saddle. Ty Stokes rode standing on his neck with his feet straight above the saddle. They used to say that for variety few cowboys belonged in the same class as Ty Stokes."

In 1921, the inaugural Fortuna Rodeo was held as entertainment for the annual Humboldt Stockmen's Association picnic. This first rodeo was more of an exhibition, with hired riders, and Stokes was one of the performers. His act at the Livermore rodeo that year indicates what his performance was like. The Oakland Tribune reported Stokes would "ride steers, trick ride and rope, but also he will get down off his horse and fight bulls from the floor of the arena. When he isn't working along these lines he will provide comedy stuff, and he has a lot of it." Thus, Stokes was becoming a clown, one of the most dangerous of rodeo occupations, as clowns both entertained the audience and protected riders from dangerous bulls. Stokes also continued to participate in arena events. In her book Fearless Funnyman, Gail Hughbanks Woerner explains that this was a common path for early rodeo clowns. They did not make enough money as funny men of the rodeo and supplemented their income by competing.

In August of 1921, Stahl and Stokes both performed at the Petaluma Rodeo, the Petaluma Argus-Courier reporting "Ty Stokes and Jesse Stahl (colored) have arrived for the rodeo. They are known as the 'Buckaroo Twins' among the rodeo riders, and are great performers and are also known throughout the state by the followers of rodeos." Their exploits at the Petaluma Rodeo included "the outlaw automobile," a routine in which one of them tried to rope an animal from the car while the other drove. Another of Stokes' skills was tricks with a rope; he could keep six ropes spinning simultaneously.

Starting in 1922, the Fortuna Rodeo became a contestant rodeo and Stokes continued to enter the rodeo as a rider and clown. In 1924, the Humboldt Beacon reported, "Ty Stokes, the Black Ace of cow punchers signified his intention of being present and will not only do stunt riding but will also enter the competition and it is predicted by those who know the riders of the Pacific Circuit that Ty will give them a hard ride for their money." The Fortuna Advance also added that Doug Prior, of the Tooby and Prior ranch near Alderpoint, would be bringing in "the wild mule ridden last year by Ty Stokes and which has never been ridden since." The Advance reported after the rodeo that Stokes had, "as usual, played the clown with the assistance of his donkey." For the next four years, Stokes continued to follow the Pacific coast rodeo circuit, expanding his repertoire to include mules he had trained to do tricks.

In April of 1929, Stokes was admitted to a hospital in Fairmont, where he died of a heart attack at the age of 44. The Hayward Daily Review reported his death under the headline, "Noted Figure of Wild West Shows Rides Last Steed." The paper describes Stokes as "one of the most noted of the Negro riders in wild west shows between Cheyenne and the Pacific Coast. It was said of him that he could ride anything on four legs."

His obituary in the same paper captured the respect Stokes' friends on the rodeo circuit felt for him. Under the headline, "Ty Stokes, Noted Rodeo Rider, Laid to Rest by Friends," the article begins, "The tumultuous and spectacular career of Thomas 'Ty' Stokes, noted Negro rodeo rider and horse breaker was given a fitting climax Wednesday afternoon in one of the most unusual funeral services held in many years. Cowboys ... associated with him ... assembled at the Sorenson Brothers mortuary, a number of them clad in their finest and most vari-colored costumes to pay him their last tributes of respect and admiration. The Rev. Richard C. Day ... paid an eloquent tribute to the man who had won affection across the barriers of race by his courage and comradely qualities. In the procession to the cemetery ... the favorite horse of the dead man was led behind the hearse with a huge purple garland across the saddle to denote the rider would ride no more ... Harry Rowell owner of the ranch where ... [Stokes] had ridden in two rodeos was prominent among the mourners. Pallbearers were: Jack Bayliss, Tex MacKinnon, Frank Duarte, Lee McKinney, Jesse Stahl and Harry Rowell."

Stokes' passing continued to be marked that year at many of the rodeos in which he had performed, including the Fortuna Rodeo. In the August Roaring Camp Nugget, the program for the Fortuna Rodeo, an article was included to explain Stokes' absence. Under the headline "An Absent Face," the Nugget notes "The missing one is Ty Stokes, the old colored man who at every Rodeo, since its inception here, has amused the children and the grown-ups too, with his clown stunts. ... Ty won't be here no more 'cause Ty has gone to another land where the ponys [sic.] don't buck and they say the streets are lined with gold, and angles [sic., angels] look after the good old colored men. Ty passed into the great beyond at Hayward a few months ago. Old friends attended the funeral and the floral tributes were many and beautiful." Alongside the affection felt for Stokes can be seen a possibly subconscious attempt to minimize his legacy: recalling him as a clown rather than a rider, and as an "old colored man" rather than a performer who held his own against all competitors, of whatever race.

The lives of Stahl and Stokes read like an old western with their prowess in the saddle and many accomplishments. Both men were able to overcome many prejudices of their era due to their abilities and the fulfillment they found in demonstrating their skills. Certainly, however, they could both have accomplished even more if their careers had not been stymied by the racism of the time. In spite of the challenges Stahl and Stokes faced competing on the rodeo circuit some 30 years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball, with their incredible skil as riders, both men proved themselves time and again to be champions of the rodeo.

Susan J.P. O'Hara grew up in Humboldt County and has worked as a teacher for the past 29 years and is currently teaching at Casterlin Elementary in Southern Humboldt Unified School District and chairs the Fortuna Historical Commission. She and Alex Service have written several books on local history, their most recent book is Mills of Humboldt 1910-1945.

Alex Service is curator of the Fortuna Depot Museum, located in Rohner Park adjacent to the Fortuna Rodeo grounds. She is also active in community theater, and combines her loves of history and theater in Fortuna's annual Grave Matters and Untimely Departures cemetery tour.

More by Alex Service

-

Return of The Valley of the Giants

- Nov 2, 2023

-

Not Expelled But Not Fully Welcome

Japanese experiences in Humboldt's Chinese exclusion era, from education to terrorism

- Aug 24, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023