Albert and the Baskets

The Clarke gains a collection that reveals a tradition saved

By Heidi Walters[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

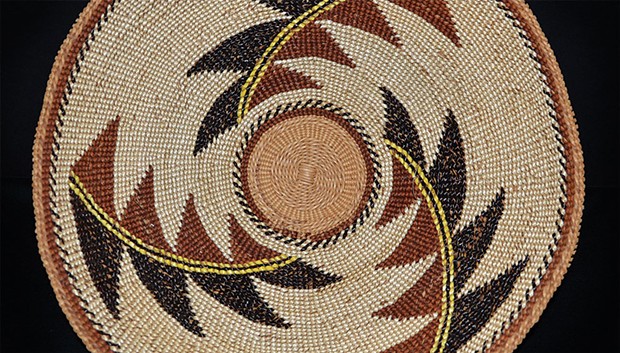

The women in her family made baskets — Yurok, Karuk and Hupa women who, since time immemorial, went into the woods and hills to gather sticks and bark, lily stems and other materials, then pounded, split, dried, dyed and bleached them and wove them into beautiful, strong tools. Baby carriers, hoppers, cooking and eating bowls, trays and, after whites arrived, more decorative items made to sell.

Vivien Risling Hailstone, who was born in 1913 at Moreck on the lower Klamath River, learned to weave, too. But she didn't take it up seriously until she was in early middle age. As a child, like many of her peers, she was forced into the Indian boarding school in the Hoopa Valley, where their native culture and language was beaten out of them. Girls could no longer go out with their families to burn the hazel-stick and bear-grass collecting grounds, to pick ferns and willow shoots and wolf lichen. They couldn't practice their weaving.

"That's the place where they took the Indian out of you," Vivien recalls in the video "Through the Eyes of a Basketweaver," produced by the California Indian Basketweavers Association. "... They took away our language, our songs, our way of life — and when that happens, you're nobody. You're just floating."

In the early 1950s, Hailstone began tugging on those old threads of her youth, the old ways, and pulling them tight, trying to anchor her people back to their culture in some way.

It started after she and a partner opened the I-Ye-Quee Trading Post Gift Shop in the Hoopa Valley, and began selling baskets made by local weavers. The baskets were beautiful, and she often kept some and brought them home, recalls her son Albert Hailstone. But she began to worry: There weren't very many weavers anymore, and some day these women, these friends and relatives of hers, wouldn't be around to make baskets or pass on their knowledge to new weavers. So Vivien and her friends started basket weaving classes.

Vivien ran the gift shop for 40 years and, as she grew older, she began sending pieces from her basket collection to Albert, who had moved to San Francisco in his 20s.

He kept those baskets she gave him. And he collected more on his own, displaying a few on shelves in his home and storing the rest. After Vivien died in 2000, Albert found more baskets in her home and preserved them, too. Two years ago, he and his partner, Gene, moved to Eureka to retire. And this year, Albert donated his and his mother's joint basket collection to the Clarke Museum. The collection is the Clarke's to keep and protect, and will be on display through September 2015. After that, at Albert's request, at least 20 baskets will be on display at any given time.

The Vivien and Albert Hailstone Collection, featuring Yurok, Karuk and Hupa works mostly from the 1940s through 1980s, complements an earlier donation to the Clarke, the Hover Collection, whose baskets date from the 1880s to the 1930s. The Hailstone Collection is rare in that the names of the creators of nearly half of its 219 baskets are known. There are some ceremonial caps and also some older work baskets. But most are "trinket" baskets, strikingly designed decorative pieces created by Vivien, her friends and relatives. These weavers not only were among the best of their time but, spurred on by Vivien, they sparked a basketweaving revival at a time when the art was in danger of dying out.

At 72, Albert is slender and white-haired, a soft-spoken man who appreciates finely crafted things, history, political intrigue novels and the sound of the first geese returning for the season. He has firm opinions, he says, and jokes somewhat unconvincingly that people avoid him because of it. He's writing a book about his family's history.

But there was a time when his aptitude as a preserver of tradition, and of examples of a mid-20th century revival period in Northern California basketweaving, might have been doubted.

As a teen in the mid-1950s, Albert had to work after school in his mother's gift shop. "It was brutal," he says, semi-seriously. A lot of tourists and locals passed through, and Albert was social, so he liked the interaction. But he would rather have been running around with his friends.

When Albert turned 15, Vivien packed him off to Modesto to live with her brother David Risling Jr., who was a teacher at Modesto Junior College.

"My mother was concerned about education," says Albert, "and also I was starting to make friends with people she was getting concerned about."

It took several months for Albert, a country kid from a quiet valley with maybe 400 residents, many of them relatives, to adjust to the city pace. Modesto High School alone, where Albert spent his junior and senior years, had 3,000 students. But soon he loved his new life.

After high school, he lived briefly in Hoopa again. A few years after the 1964 flood, which ravaged the valley, he and his family moved to Redding. Albert went to community college there for two years. Then he met a cousin who'd become a hairdresser in San Francisco after taking advantage of vocational training funded through the Indian Relocation Act of 1956.

"I went down and visited her, and I thought, 'Oh my god, she did this in nine months and she has her own apartment, and this and that.' I was never good in school, and I was tired of lying and telling everyone I was going to be a doctor to get them off my back."

He wanted to try commercial art, but was told there was a five-year wait to get into that program. Well, he asked, then what about hairdressing? It wasn't something he'd ever dreamed of doing, but they said that was just a six-month wait so he signed up. Soon he had a job at a salon in San Francisco. But he got bored with the repetitive stream of updos. "All you did was throw in rollers, put 'em in the dryer, comb 'em out. And when they're under the dryer you're not talking to them!"

He quit, and cast around for a few years trying on other vocations. One day, he says, he started noticing there were people with all kinds of new haircuts walking around the city. He asked a few of them who did their hair. "Yosh," they said. Yosh Toya, he learned, was the former assistant to Vidal Sassoon — the man who had saved the world from boring hair with his ready-to-wear-cuts revolution. Albert trained with Yosh and got back into hair. The process was more fun and gave him time to chat with his clients. "And you could charge more money," Albert says.

He was 30, and had finally settled down. His mother started sending him baskets.

"She'd say, 'Why don't you take this one? I've enjoyed it; you enjoy it for a while.'" Albert says. "Or she'd say, 'You know, I'm going to sell this one; you'd better take it.'"

His mother often visited him on buying and selling trips to the city, and they talked a lot about baskets. They talked about the work that went into making them, and about how important it was to share the beauty, and complexity, of this art with more people so that it could survive into the future.

"For me, the past begins with my great-grandmother [Jane Young]," says Vivien in the video by the Basketweavers Association, a group formed in 1992 to advocate for the art and for preservation of gathering grounds. "She was born before there were any white people. She was born in the 1840s. She was the storyteller, she was the historian, she was the teacher, the babysitter. She'd tell us about before there were people, about the animal times. And then she'd tell us about the early history of our people, and about what happened when the new people came in. She was a great influence on my life."

Her father, David Risling Sr., a ceremonial dance leader, showed her how to regain some control over a present determined to wipe out that past. He helped turn the boarding school she had been forced to attend into a day school; eventually it became Hoopa High School. Her mother, Geneva Orcutt Risling, was "the backbone" of the family who taught her to respect all things. Vivien herself was a modern woman for her time, raising a family and running a couple of businesses. During World War II, many Hoopa families moved to Eureka where there were jobs. Vivien and her two sisters worked in the shipyards — Vivien as a welder. Albert, her first son, was born in Eureka in 1942. Her husband and brothers, like many Native American men, went off to war and one of her brothers died there. When the war was over, the family moved back to Hoopa where a post-war lumber boom allowed Vivien's husband, Albert Hailstone Sr., to resume being a logger and Vivien and her brother Anthony to run the only Indian-owned sawmill, started by their father, among the many new mills that sprang up in the valley.

Albert Hailstone remembers his mother as a bright, business-minded woman with numerous interests. Besides doing the books and scaling at the family sawmill, she joined organizations and, in the early 1950s, she and her partner opened the I-Ye-Quee Trading Post Gift Shop.

"It was very small," Albert recalls. "And you're not going to make it selling just Indian things, so it also had gifts and sundries and magazines. It really did serve the local community."

But Vivien was ready for the tourists.

"I remember she and a friend went to the Southwest and came back with turquoise and silver and a couple of rugs," says Albert. "That was the Indian things."

That, and locally made baskets.

"She knew a lot of weavers, and met a lot of weavers as a result, and she was able to see what was being made," Albert recalls. "She began to realize our basketweavers are getting old and there aren't many new ones; our designs could be lost."

The repression of local native culture was compounded by the influx of non-Indian residents who came to take advantage of the lumber boom. As Vivien relates in the video, "The public schools doubled in size. ... The teachers were non-Indian."

Starting in the late 19th century, collectors — some say because they thought Indians were disappearing — began snapping up baskets for museums or to furnish "Indian rooms" in their own homes. Weavers began making fancy baskets with more elaborate designs and non-traditional forms: trays strictly for display, miniatures with ornate lids, covers for jars (the Hailstone collection includes salt and pepper shaker holders). But by the end of World War II, general interest in "Indian things" had waned.

In an attempt to preserve local designs, Vivien and her weaver friends started a pottery guild to build pots from native clay and paint them with local native designs. But clay work wasn't typical for the region.

"After a while it became clear, this was a nice attempt ... but it's not the real thing," says Albert. "So that's when they started basket classes."

His mother got a grant and she and the other weavers taught weaving in Hoopa. Then Vivien petitioned College of the Redwoods to carry basketweaving classes. They laughed at her, says Albert. It was considered "women's craft" or just "part of old Indian things." So Vivien got on the board that determined curricula and, by the late 1960s, was teaching basketweaving at the college (and she taught it for several decades after). It was important to Vivien that her students understand the culture and environment necessary to make a basket. As Albert writes in an introduction to the collection, "Teaching weaving is more than twisting sticks and grasses together. It's a philosophy — a way of observing seasons and understanding the Earth; it teaches you to plan ahead. Weaving begins as you gather your materials. That means when you weave a basket you actually started it last year."

You have to know where and what time of year to collect the plants that provide the sticks, stems and dyes for your baskets. There have to be enough of them of the right size for your project. And once you get them home you have to have the time to prepare them and, later, weave them.

"Say you spent the day out picking sticks, well, who's going to peel them?" Albert says. "They have to be peeled within so many hours, or they're going to be useless."

Bear grass (a lily) and hazel grounds have to be burned a year before gathering can take place. In late summer or fall, Woodwardia ferns have to be picked and their stems hammered right away while they're moist to get to the two strong fibers inside. Maidenhair fern stems have to be split to separate the red side from the black. Roots exposed by high rivers in winter have to be gathered. All of this takes time.

"It didn't matter if students were Native American or not," says Albert. "My mother enjoyed it. She figured the more people that knew about it, the more respect [there would be for the art], and the more value."

It wasn't easy reviving basketweaving. The federal government banned burning, and logging and pesticides impacted collecting grounds. Weavers struggled to convince land managers to burn traditional gathering areas to promote growth of good weaving materials. It helped that a wave of Native American activism and cultural revival was sweeping the nation. Albert's uncle David Risling Jr. was at the forefront, developing Native American Studies programs at the University of California, Davis, and elsewhere, and co-creating the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian. He's considered the "father of Indian education."

Today, says Albert, new weavers carry on the traditions. Some men still weave eel-traps. Some women still make baby baskets, acorn bowls and trinket baskets for family and friends, but don't have much time to make any to sell.

"You have to make a hundred baskets to become a master," Albert says. "The newer basketmakers, they have families, they have many interests, their lives are scattered in interesting ways. They'd like to sit down and do baskets, but they have to do it when they can. ... And you have to be in a good frame of mind. You can't make a basket when you're upset, or when you're angry. Because you'll make mistakes."

Although he's spent most of his adult life away from the Hoopa Valley, it makes sense that Albert shared with his mother an innate love and respect for baskets. He grew up surrounded by them. Everyone had baskets. Babies, including him, his brother and their many cousins, were strapped into them as infants. Baskets were used in ceremonies, as regalia or to cook acorn soup and other traditional dishes. And Albert's grandmother, who lived with them and babysat him in the daytime when he was little, frequently had friends and relatives over who were weavers.

"Often somebody would knock on the door and it would be an elderly lady or two or three and they would have a little sack in their hand, and I knew immediately, 'Oh, they're going to make baskets today,'" recalls Albert. "And then my grandmother would set it up: You need buckets of water to make the materials pliable, so out they would come. Then they would sit and — when you weave, it's like a sewing bee. You talk, you gossip, you laugh, you talk about your grandkids. I would wander in and out. Sometimes they would be speaking Indian, which I didn't know. ... Sometimes when they'd lapse into Indian I'd think, 'OK, they're talking about somebody, and I'll never know.'" He laughs and adds, "That's the stuff I wanted!"

About 10 years before Albert's mother died, he told her not to worry about the baskets — he planned to donate them someday to a museum where they would be protected.

Ron Johnson, a retired Humboldt State University art history professor and the special exhibitions curator for the Clarke Museum, helped prepare the collection for exhibit. It contains amazing works, he says, such as Yurok weaver Amy Smoker's finely woven miniatures.

"[Smoker's] work is very tight, and often there are a lot more strands per inch" than in others' baskets, Johnson says. "And she has a wonderful sense of pattern."

Coleen Kelley Marks, a former Clarke director-curator, appraised, cleaned and reshaped the baskets in the Hailstone collection. With this addition, she says, "the Clarke has the finest collection of Northwestern California baskets of anywhere in the world."

Marks interviewed several of these weavers in 1982 for an oral history project. They were the master weavers, she says.

"Carrie Turner started weaving when she was about 5 or 6 years old," says Marks. "When she was 12, she sold five ceremonial caps to a white trader who came up the river. Her father negotiated for her. She got a dollar for each, and bought her first pair of shoes with that money."

One large case in the Hailstone Collection contains baskets by Nettie McKinnon. Albert, in the museum one recent afternoon, gets tears in his eyes as he points out baskets McKinnon wove when she was young and strong, and then ones she made in her final years: "You can see a basket maker at her end," says Albert. "Her mind is good, but her strength isn't there, her weave is weak, her shape isn't as controlled. But the count is still good. And so you're watching her become old. I thought this was so wonderful. It puts a complete face on a basket maker. You know, you don't die on the top of your game."

It's because of such masters — these mothers and grandmothers who've mostly passed on — and their interest in the future, that basketweaving lives on.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Lincoln's Hearse

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023