'A Brutal End'

The Great Timber Strike of 1935 and lessons from our past

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

As the sun crested over a hazy sky on Labor Day, a steady if shallow stream of shoppers ambled into Eureka's Bayshore Mall from the parking lot. As they went, overlooking the sidewalk between the Boot Barn and the food court, they passed an old, worn copper sign commemorating one of the darker chapters in local labor history. A couple of miles to the north, in the briefing room of the Eureka Police Department headquarters, above a series of plaques commemorating good police work, hangs a glass case displaying a .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun.

The plaque and the gun remain two of the last publicly visible artifacts of the Great Lumber Strike of 1935 and the events of June 21 that year, which are alternately described as a riot or a massacre, depending on who's doing the accounting. And while the gun's history remains somewhat uncertain, it — or one just like it — became the symbol of the bloody clash between striking lumbermen, police and private security guards, even though it's unclear whether the gun was used to shoot anyone that day, much less take any of the three lives lost.

Almost 90 years later, the events of that day — seemingly long forgotten in popular local lore — carry reverberations that can still be seen today, as, at its core, the story of the Great Lumber Strike is a story about power.

The Strike

While work in local mills would come to provide the financial bedrock for generations of Humboldt County families, offering the kind of well-paying jobs today's politicians talk about wistfully in high-stakes deliberations about what kind of industry to welcome to the area, there's no escaping that in the early 1930s life in the mills was rough.

The Great Depression gutted the timber industry, as demand for lumber plummeted amid a glut of supply. As a result, hundreds of thousands of mill workers in the Pacific Northwest lost their jobs and wages dropped. By 1935, demand had started to rebound and about 10 percent of Humboldt County's population worked in the mills, where they generally earned 35 cents an hour for a 60-hour work week. Most lived in poverty.

The workforce had sporadically attempted to unionize in the early 1900s but such efforts were quickly squashed, with lumber companies blacklisting union leaders and "sympathizers." But by 1935, a national labor movement had taken hold and the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act, signed into law by Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, had given all workers the right to collectively bargain.

In early 1935, as high-powered national unions began plotting a strike throughout the Pacific Northwest, Humboldt County's Lumber and Sawmill Workers Union formulated its demands: 50 cents an hour, a 48-hour work week and recognition of its union. A short time later, however, the Norwest Council of Lumber and Sawmill Workers met in Aberdeen, Washington, and set its sights much higher, demanding 75 cents an hour, a 30-hour work week, overtime and holiday pay, and union recognition, according to Organize! The Great Lumber Strike of Humboldt County 1935 by Frank Onstine and Rachel Harris. The following month, a fiery representative of the larger union, Abe Muir, traveled to Eureka and persuaded the local union to drop its demands and stand with millworkers and lumbermen to the north, matching their demands.

"Muir gave a demagogic speech in which he said that if a strike was called, 'no carpenter anywhere in the country will touch a piece of redwood lumber, no painter will paint it, no electrician will put electrical wiring into a home built with redwood, no railroad worker will ship it, no seaman will haul the lumber ... and we will force these lumber barons to their knees,'" Onstine and Harris' account states. "In Washington and Oregon, higher wages and stronger local union organization made the demands of the Northwest Council seem realistic. In Humboldt County, however, the idea that a fledgling redwood local union could force the lumber barons to double wages, to cut the work week in half and — simultaneously — to recognize a union for the first time strained the bounds of credibility."

But members who spoke in favor of postponing a strike and holding to the more realistic local demands were shouted down by Muir as "company agents," and Muir's proposal carried the day. On May 15, Humboldt County workers joined a strike that included much of the West Coast lumber industry. Picket lines soon followed.

The companies responded with a public relations offensive that saw so-called loyalty oaths circulated among their workers, who signed under duress or threat, according to some union reports, and were then excitedly reported by Eureka's two daily newspapers, the Humboldt Times and the Humboldt Standard. Both papers had run front-page editorials denouncing the strike, with the Standard proclaiming it "little short of criminal." Within days, Eureka Mayor Frank Sweasey announced the establishment of a "committee of 1,000" to "guarantee the safety of the citizens and property owners of Eureka" during the strike, according to Onstine and Harris' account.

"The strength of the strike is difficult to assess because of conflicting reports by the newspapers and the union," they write. "My own estimate is that about 1,000 workers were involved at the peak of the strike and that about 300 were still out by the end."

Harris and Onstine surmise that while many were sympathetic to the strikers, more workers didn't join because of its timing — coming just as many millworkers returned from winter layoffs — and many simply judged it to be a "lost cause."

But there were larger signs of support from the general community. The local chapter of the International Longshoremen's Association stood in solidary with the strikers, pledging not to ship any lumber produced at the involved mills, and donations from some local businessmen, farmers and fishermen were enough to keep a "strike kitchen" feeding several hundred people daily for the strike's duration. And union leaders continued to argue better wages and working conditions for millworkers would benefit 99 percent of the local populace.

For about a month, striking workers picketed local mills, forcing those still working to "run the gauntlet" while crossing the picket lines.

By early June, tensions had escalated. The union reported that the lumber companies had hired a squad of "thugs" to intimidate picketers while local newspapers reported on a number of "near riots" along the picket lines and published stories about picketers scouring the city for rotten eggs to throw at workers or spreading tacks on local roads, reports the union disputed.

The mills and local law enforcement were readying for conflict, according to Onstine and Harris' account, which includes a letter from teargas salesman Joseph Roush to his superiors detailing $1,272 in sales to the Hammond Lumber Co., as well as deals to outfit the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office and the Eureka Police Department.

"I gave a short training course to the various law enforcement groups and guards and they were more than enthusiastic about the equipment," the letter states. "If any serious trouble breaks out I think that I will be able to sell them at least three times the order which I have already delivered, which amounts to quite a bit."

June 21, 1935

By mid June, the ranks of the strikers had waned to only the most devoted and reports that a return-to-work movement among local longshoremen was gaining strength made the strike's end seem inevitable. On June 20, news circulated that bigwigs from the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and the International Longshoremen's Association were coming to Eureka to gauge the strength of the picket lines, prompting the local union to issue a strike bulletin. Under the headline "Now or Never," it invited every one of its members to attend a meeting that night.

During the tense meeting, the union decided to consolidate its efforts and send all picketers to a single mill. The following morning, they were directed to the gate of the Holmes-Eureka Mill, which sat along U.S. Highway 101, where the Bayshore Mall now stands.

By 6:30 a.m., approximately 200 strikers had gathered, according to Onstine and Harris' account, and some created a makeshift barricade of old pallets and wood across the mill's sole entrance.

"Non-striking workers began to arrive almost as soon as the pickets had gathered," their account states. "Confronted with the determined picketers, most simply turned around and left. Witnesses later recounted that some youngsters in the group of pickets began throwing rocks and pieces of concrete at the strikebreakers' cars, although this was contrary to the union's directive to the pickets."

When security officer James O'Neill arrived at the mill in his family car with his wife to start his shift, picketers pushed the car halfway across the road, at which point a woman reportedly threatened them with a rock, prompting O'Neill and his wife to flee for the police station, where they summoned help. A full police response ensued.

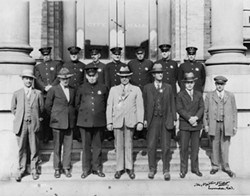

Then Eureka Police Chief George Littlefield arrived at the scene in a brown Packard Sedan driven by O'Neill, who would go on to later become a captain with EPD and become grandfather to current EPD Capt. Patrick O'Neill.

"Several witnesses watching from the flats above said that when the pickets stopped Littlefield's car, he climbed onto the running board, pistol in hand, and began firing into the ground, shouting, 'Who's going to stop me?'" Onstine and Harris write.

Mickie Lima, a picket captain that day, told Onstine and Harris that seeing the escalating scene, organizers had decided to pull the picket line because "the situation looked very dangerous." But as picketers began to disperse, some of the officers began firing their newly purchased teargas canisters.

"They were firing tear gas bombs out of a rifle, like a sawed-off shotgun type of rig," Lima said. "One of the women who was picketing, who was behind me, let out a scream and went down in a heap. I ran back to her thinking that she had been shot with a shotgun."

The woman had been hit with a teargas canister, Lima said, but he didn't know that at the time and, feeling blood underneath her, he "imagined it was much worse than it was."

"I yelled to a number of guys and they started back towards me," Lima said. "I yelled that they shot her in the back with a shotgun and yelled for somebody to get a car. Then quite a number of pickets came running back and finally they said, 'Let's get the bastards.' We charged the police and that's when they took a dumping, including Littlefield."

Violent chaos ensued. As strikers attacked the police with rocks, officers opened fire into the crowd.

"Chief Littlefield was overpowered and beaten senseless with his gun by a Native American striker identified as Barry Phillips," Onstine and Harris' book states. "Several other officers were also disarmed and beaten with their own billy clubs and pistols."

A 1995 article in the Times-Standard notes that O'Neill came to Littlefield's defense, saying, "I started shooting at legs. It looked like they were going to kill him, though, and I began to shoot for bodies."

Onstine and Harris capture two scenes that illustrate the confusion and terror of the scene. In one, two officers arrested Virgil Hollis, throwing him into a police car prior to the eruption of violence, only to have Hollis drive the injured officers to the hospital after they retreated back to the safety of the car. In the other, an officer emptied his revolver through the windshield of his patrol car when it was besieged by picketers and then sped off "to find someone who could operate the submachine gun in the back of his vehicle. He quickly returned with Ernest Watkins, a young Holmes-Eureka employee. Watkins proceeded to open fire but the gun jammed and he was only able to discharge a few rounds."

During the melee, picketer Wilhelm Kaarte, 63, was shot in the throat and killed, and Harold Edlund, a 35-year-old Pacific Lumber Co. employee, was shot in the chest while attempting to help him. Paul Lampella, a 19-year-old bystander who was reportedly just lying on the ground, watching the events unfold from a distance of about 400 feet, was shot in the head. Edlund and Lampella later died of their wounds.

Dozens of other picketers were injured and five police officers were treated at a local hospital for gas exposure, cuts and concussions, according to Onstine and Harris, though "all returned to duty later that morning."

It was never publicly reported who shot Kaarte, Edlund, Lampella or the other picketers wounded the morning of June 21, 1935 — though there were no reports of picketers returning fire from officers and security guards. It's unclear if who fired the fatal rounds was ever a subject of investigation.

Aftermath

The official response to the events of that morning was swift, as police and a rumored group of "G-men" rounded up picketers and protesters by the dozen. At the direction of the police department, the local fire department even cleared a poor section of the city — a cluster of wood shacks known as "Jungle Town" — and burnt it to the ground, despite protestations from residents that they had been 'bitterly' against the strike," according to an article in the Humboldt Times.

Police repeatedly cast the picketers as radicals, outside agitators and communists — allegations parroted by the newspapers. In one almost comical example unearthed by Onstine and Harris, police reported finding a "secret door" at the Finnish Federation Hall that contained old clothes "for needy radicals who come to the city" and a box of weapons with "pistols of many makes, daggers, knives, billy clubs and communistic literature."

"It was later learned," the pair write, "that the secret door was a closet located near a stage in the hall; the old clothes were costumes; and the weapons were props made of wood and rubber."

Nonetheless, the Humboldt Times cast the police actions as having brought order to chaos in the following day's paper.

"One of the bloodiest outbreaks of mob violence in Eureka's history was replaced by peace and order last night, after federal, state, county and city officers combined to round up nearly 150 rioters and suspected radicals," the story's lede read. "Although considerable tension continued, officers believed their action had broken the back of a terrorist campaign launched by communist leaders yesterday morning."

Two days later, both the Humboldt Times and the Humboldt Standard ran front page stories warning that "truckloads" of "radical sympathizers" were headed to the county from Oregon and elsewhere, according to Onstine and Harris.

"Vigilantes were assigned to stop all cars approaching Eureka from the north and south, and anyone who looked as if he might be a 'radical sympathizer' was forced to turn around," they write.

While the strike ended June 21, 1935, the fight soon moved to local courtrooms, where more than 100 people were to face charges of rioting. Only a handful stood trial, with one acquitted and others ending with hung juries after several responding officers were found to have perjured themselves on the stand. By the end of September, the district attorney had abandoned plans to bring any other cases to trial. No charges were ever brought against police officers or private security who shot teargas canisters or opened fire into the crowd.

The Times-Standard concluded in its 1995 retrospective: "The brutal end of the labor movement's effort to organize the lumber industry in 1935 was a deterrent to union efforts for nearly a decade."

'Don't Want to Forget'

On Aug. 19, 1995, the city of Eureka held a dedication ceremony to place the plaque on the Bayshore Mall to — 60 years later — publicly acknowledge the bloody day the timber strike ended. Then state Assemblymember Dan Hauser, local labor leaders and city officials gave speeches before the rectangular bronze plaque was unveiled, memorializing the day and commemorating the deceased.

Then Police Chief Arnie Milsap opened the proceedings.

"I want to make it perfectly clear: You'll never see me — never see me — riding on a running board into the middle of a crowd firing my gun in the air," he said, drawing laughs and claps from the crowd, according to Onstine and Harris. "The labor movement has contributed much to this country. Everywhere you go, you see evidence of it — the streets, the buildings, the waterways — everything that we take pride in for being part of a civilized society was built by people, many of them union members, many of them nothing more than conscripted people from foreign lands."

Milsap then invited anyone from the public to — for "historical purposes" — come down to the police department to look at the tear gas guns and the Thompson submachine gun used on June 21, 1935, which he described as part of an "ancient past."

"We can't escape the tragedies or mistakes that were made 60 years ago; we don't want to forget them and we don't want to relive them," he's quoted as saying by Ornstine and Harris. "We use those as building steps, to build a better future."

What Milsap apparently didn't tell the crowd that day is he'd taken a liking to firing that submachine gun.

William Honsal Sr., a retired longtime EPD captain, said he remembers that when he started with the department in the early 1970s, Milsap, one of his training officers, would occasionally get out the Tommy gun and let officers fire it in the shooting gallery that used to be in the basement of the Humboldt County Courthouse. At the time, Honsal said Milsap told him the department had purchased the gun in the early 1930s, though he was never explicitly told it was used that day in 1935. Honsal said the gun stayed in the armory, and was never displayed or used outside the shooting gallery while he was at EPD.

When first contacted for this story, current EPD Chief Steve Watson said he didn't know the gun's history or how it came to be displayed in the department's briefing room, adding that the city has no records detailing when it was acquired. He's since dispatched a detective — who's also an amateur history buff — to research the gun's past but, as the Journal went to press, had been unable to authenticate it, though he did hear from former Chief Ray Shipley that he vaguely recalled a news report about a Thompson submachine gun being added to the department's armory in 1950 or 1951, before he became chief.

If the gun is determined to be the one used June 21, 1935, Watson said it would obviously have a "historical significance" and he'd work to figure out an appropriate use for it, perhaps putting it on display in a local museum, if laws allow.

Whether it's the Tommy gun sitting in EPD's briefing room or not, the gun taken up by a millworker in 1935 seems to have played a minimal part in the gruesome events that unfolded at the gate of the Holmes-Eureka Mill. That it would become one of the enduring symbols of that day — splashed on newspaper front pages — is itself curious, and probably a sign that Humboldt County still has a lot to learn from its past.

Thadeus Greenson (he/him) is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

more from the author

-

Failed Leadership

- May 2, 2024

-

'On Siemens Hall Hill'

How an eight-day occupation at Cal Poly Humboldt divided campus

- May 2, 2024

-

Failed Leadership

- May 1, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023