[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Whether we realize it or not, all of us are designers. And all design is ecological design in that it either hurts or helps nature, regardless of the intent. As gardeners, whether forging paths, building beds or pruning trees, we are always designing. Every choice we make affects the whole and when we become conscious of that fact, we can engage the process in ways that make our gardens more beautiful, easier to maintain, more abundant and, ultimately, better connected to the larger ecosystem.

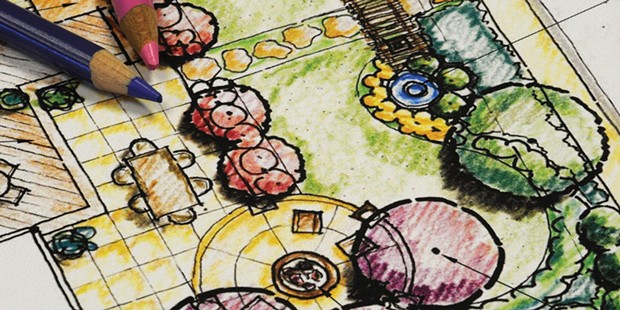

Clarifying goals and ideas by getting them down on paper creates a carefully thought-out road map for implementation that saves time and money, prevents mistakes and helps communicate ideas to others. It is much easier to correct mistakes on paper than on land. Of course, your long-term needs and goals will change and a good design leaves plenty of room for that.

Try GOBRADIME

This is an acronym for Goals, Observation, Boundaries, Resources, Analysis, Design, Implementation–Maintenance/Monitoring and Evaluate/Enjoy. Since 1999, I have spent a lot of time studying and practicing permaculture — defined as "a design system for sustainable living." A detailed overview of permaculture is more than we have space for in this column, but it was through these experiences that I developed GOBRADIME, which is a concise, step-by-step process for making a clear, tangible plan for your garden. And while I could easily write an entire book on GOBRADIME, I can offer this quick two-part introduction with confidence that it will help you through that "what do I do now" feeling that so many of us experience at the beginning of the garden season.

So take some time on one of these rainy days to work through it. Whether you choose to grow just a few small beds of annual vegetables or turn your entire site into a perennial food forest, this will help. Work through the first half of the steps on paper and in your mind. Then, when you get to Implementation, you'll have a deliberate action plan ready to go.

Goals. The first step in any design is to identify personal and collective goals. What do you want to accomplish and why? Write down and prioritize a list of goals, rating each one on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing the highest priority. Then sort the list so that the things you want to accomplish first are at the top. This will help you develop a timeline later on.

Observation. This is the heart of ecological design and the key to finding and cooperating with nature's patterns and cycles. Learn to read the land. Watch where the water drains and where it collects. Notice subtle changes in your soil, see where the shade falls, where the moss grows, where the mushrooms come up. Learn the names of all of your weeds and learn what they do for the soil. Lie down on the ground and look up at the world around you. What do you see? How do you want to change it? What is the most effective and most ecological way to proceed? Take your time, make educated choices and try to avoid irreparable errors, but at the same time don't be afraid to experiment or make little mistakes. That's how you learn!

Boundaries. Find and establish boundaries. Draw a base map of the site. Pace or measure each distance on the ground and do your best to develop a map that is to scale. Note the following things on the map: buildings, irrigation, doors, decks, patios, driveways, fences, hedges, trees, garden and any other physical objects. Add in permanent and temporary paths and make note of any objects that may be temporarily missing, such as parked cars or seasonal motor-home storage. Now document how water, humans and animals move through the site, using dashed lines and arrows. This will establish the main paths through your design. Moving a well-trodden path is rarely a good idea; it is much easier to adapt the design to behavior patterns rather than the opposite, so go with the flow. Other types of boundaries might include legal or social issues such as land-use laws or potential problems with the neighbors. Try to foresee any barriers. Also, define and document your own personal boundaries. What exactly do you want to grow? How many hours a week do you want to garden? How much money will you spend? All of these factors should affect how you design your garden. You wouldn't design a huge garden if you only have an hour a week to maintain it. Be realistic. Make clear, deliberate choices.

Resources. Go back through your observations and start making lists of the resources available. Types of resources might include money, plants, labor, garden supplies, building materials, access to facilities and information from experts. Make an overlay or copy of your base map and note every potential resource, such as water, sun, compost, manure, wood piles and neighbors who might like to volunteer. What do you have? What do you need? What do you need to acquire and what can you do without? As you assemble those lists, it will become apparent that you don't need everything all at once. Rather, there will be a flow of resources in and out of the project, the nature of which will change and evolve over time. And before you go out and spend your hard-earned money on resources you think you need, try to innovate something that will fulfill the same function. Your imagination is renewable, easy to find and free.

Analysis. Now for the fun part! Analysis helps define weaknesses and brings random ideas together to form a cohesive plan. Go back through your notes and re-read everything. Envision how to use those boundaries and available resources to meet your goals.

So, spend the next few weeks working through the GOBRA and we'll pick up where we left off next month.

Heather Jo Flores is an avid seed saver and the author of Food Not Lawns, How to Turn Your Yard into a Garden and Your Neighborhood into a Community. Find her at www.heatherjoflores.com.

more from the author

-

Tales from the Underground

A rainbow of roots from around the world

- Sep 21, 2017

-

Hashtag, Bumper Crop

Veggies to plant now for fall and winter

- Aug 17, 2017

-

Plotting Out Your Garden: Part 2

- Apr 6, 2017

- More »