[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

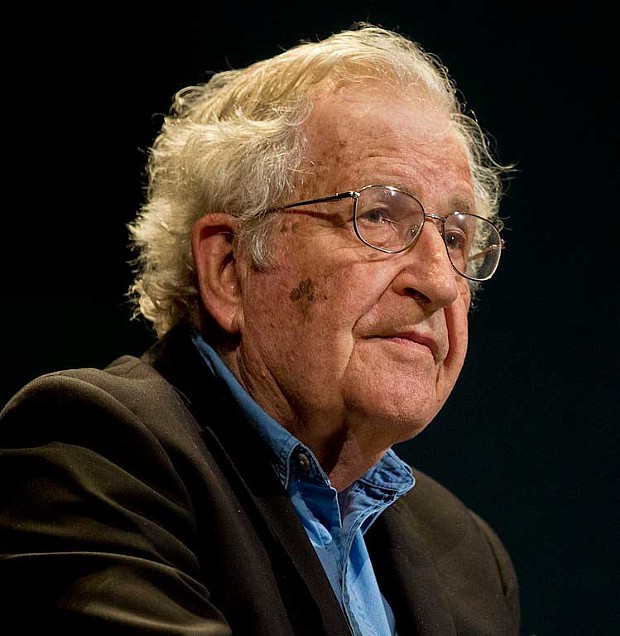

Last week I discussed linguist Noam Chomsky's theory of Universal Grammar, the idea that we're all born with some sort of "language module" that we adapt, at a very early age, to the language in which we're being raised. Here, I'm going to go into some detail to discuss a particular and tricky bit of English syntax, "multiple auxiliaries," because this construction is a mainstay of Chomsky's UG.

Consider the declarative sentence, "The dog in the corner is hungry" (using an example from Chomsky, elaborated by David Shariatmadari in his new book Don't Believe a Word.). To turn that into a question, we move the auxiliary "is" to the front of the sentence, "Is the dog in the corner hungry?" So far, so good. Now add a second auxiliary: "The dog that is in the corner is hungry." Move the first auxiliary to the front and the question becomes the odd sounding, "Is the dog that in the corner is hungry?" Yet children rarely make a mistake like this. They figure out, early on, to say, "Is the dog that is in the corner hungry?" They correctly move, not the initial "is," but the one in the main clause, to the front, and dropping the secondary "is."

How come? According to Chomsky, "You can go over a fast amount of data of experience without ever finding such a case" — the case being "question" sentences like this with two auxiliaries. This is a core finding of his "poverty of stimulus" argument. Since kids never hear such a question, he says, they must have been born with the rule already embedded in their genes. Similarly, Steven Pinker, whose bestselling 1994 book The Language Instinct brought linguistics to a whole generation of curious minds, makes the same "poverty of stimulus" mistake. He writes, "... questions with a second auxiliary embedded inside the subject phrase [like the 'dog in the corner' example above] are so rare as to be non-existent in Motherese."

They're both wrong. Such sentences are two-a-penny. Researchers who recorded endless hours of Pinker's "Motherese" concluded that double auxiliary questions are frequently used with children. Kids don't need a "language module" in their brains to learn this, they just have to listen. "Where's the other doll that goes in here?" and similar questions are commonplace in children's play environments.

So where does that leave Chomsky's Universal Grammar? Without his key arguments from "Merge" and "poverty of stimulus," there's not much left of his "nature" thesis. But let's not throw the baby out with the bathwater. The answer to my "nature or nurture" title is: yes. As with virtually every other aspect of human behavior, it's a false dichotomy. Of course "nurture" is involved — that's why we speak the language of our parents or caregivers. But "nature" has to play a role, too. Lacking any genetic learning module, we'd never pick up language in the way that everyone on Earth does, early and effortlessly. As Pinker (pretty much a Chomskyite) puts it, "There is no learning without some innate mechanism that makes learning happen."

In the case of language, the common machinery we're born with results in language universals as nouns and verbs, cases and auxiliaries and so on. The real question — what the "language wars" are all about — is whether we have a specific module devoted uniquely to language (Chomsky's claim) or whether (Daniel Everett's view, from last week) we have a general skill-learning module that humans, sometime in the last 80,000 years, co-opted for language.

In any case, language-learning can take its place in the treasure trove of universal — so presumably innate — human traits that includes: smiling as a friendly greeting, flirtation, taboo on mother-son incest, reciprocity and retaliation, property inheritance, having sex in private. What language, more than any other trait, demonstrates is the flexibility and potency of our capacity to learn. Not quite magic but pretty close.

Speaking of...

-

Language: 100,000 or 1 Million Years Old?

Feb 24, 2022 -

Black English

Dec 5, 2019 - More »

more from the author

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 3: Whodunnit?

- May 9, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 2: Problems

- May 2, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 1: Stratfordians vs. anti-Stratfordians

- Apr 25, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022