[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It was probably early morning but it felt like the middle of the night when we were awakened by the guards. We had only been in bed a few hours because of the vigil for Kambing, the baby goat who had magically joined our household one day, tiny and spindly legged, marked just like our black and white tuxedo cat. Kambing had apparently stumbled upon Pinky the cat, the least maternal creature on the planet — a fat American proto-Garfield who would exert himself only at dinnertime or to sit proudly next to the giant rats our small Philippines-born kitty St. Vitus used to kill.

My mother thought the constant crying was the baby next door. It went on and on, and Mom finally went out intending to peer over the glass-topped cement block wall. A tiny, bleating goat in our drive followed the harassed, lethargic Pinky, trying to suckle.

The little goat was almost birdlike. Holding him, I felt his heartbeat, his bones. And he was so needy. The vet was closed. Mom went into action. A tour of the Super Lux Mercado near the American School yielded a plastic baby bottle and, amazingly, canned goat milk. I don't remember Kambing ever taking to the bottle — I do remember some scissoring of rubber nipples, and dipping washcloths into warm goat milk and coaxing Kambing to try it. We took shifts. We made a bed of towels on the sun porch. Pinky, in great relief, took a nap. Blitzkrieg, our German shepherd, stood vigil with us.

Enchanting in his tininess and his orphan status, not to mention his farmyard aura, Kambing tottered straight into my heart. I was still missing the horse we sold when we had to move, still appalled by the world I found myself in, in 1960s Manila, a city where horses still pulled wagons and calesas, beaten and starved in a fashion reminiscent of Black Beauty, and where a drive through downtown showed me many children my age faring no better. In my daydreams, I grew up and returned to Manila with larger, healthy draft horses and a program to encourage the humane treatment of animals. On some days, I couldn't summon that daydream. Those days, I dreamed this whole episode of my life was a fever-inspired nightmare, like Dorothy had about Oz. I couldn't wait to awaken and tell the story to my family.

Kambing fed a need in me but we were still having trouble feeding him. As soon as school was out on Monday, Mom drove us home to pack up the goat and head to the vet's. But when we got to the clinic, Enrique, the wonderful, courtly veterinarian who was our friend and guardian angel in this strange country, was out of town. A brittle young woman with little English disdainfully declined to treat a goat.

What could we do? We went to the Super for more cans of goat milk and home to keep trying. He was bleating less. Pinky had taken to snoozing nearby instead of avoiding the sun porch and its weird inhabitant who still seemed to call him mom.

We all did our best and it truly didn't occur to me that it was not going to be OK. A few days later, Kambing was obviously, even to me, suffering and critically ill. We stayed up, sitting in the sun porch late into the night with ice for fever and warmed towels for chills, and the damned saucers of goat milk that Kambing wouldn't even look at anymore.

I fell asleep with my head in Mom's lap as she watched over our delicate patient, and I woke up to find Dad carrying me to bed. "Kambing!" I cried. Mom leaned in. "Honey, Kambing died."

I cried myself to sleep — cried for the frail little goat we couldn't save, cried for all the whipped horses I would never save, for all the puppies in the farmers market destined to be eaten, that I would never, ever save. I cried for the children I saw through the car window, children I had never daydreamed I could save — even my wildest dreams had limits — and I cried for my own innocence, which I knew would never be retrieved.

A few hours later, two slender uniformed men from the traffic kiosk awaked our household. We lived in the less exclusive gated community where many foreigners and well-to-do Filipinos resided. Forbes Park was the very expensive, fully walled, gated neighborhood with guards and patrols. Kids could probably play in backyards there. We couldn't afford it. Bel Air, where we lived, was a downscale model, with guard posts on the entrance roads but no surrounding walls.

Perhaps it discouraged large, organized home invasions. But we were regularly invaded by giant, grouchy sows from the slums surrounding us, and petty thievery was common. I couldn't go out into the fenced yard by myself. Kidnapping was an issue. Blitz couldn't either. Stealing dogs for meat was even more common.

It didn't require an adult's sophistication to wonder what kind of world we lived in.

The Bel Air guards came by in their jeep and got us all up. When they told us the president had been shot, Mom said, "Macapagal?"

I watched my mother's face when the young guard, who had lost a front tooth, said, "No, mum, President Kennedy." That moment was the end of American exceptionalism for me. I had realized America was a better place to grow up. I knew I was lucky to be born an American. In the U.S., we never had fenced yards. The whole neighborhood played touch football in the street. Although Mom and Dad were careful to talk to us about the Filipino realities with neutral respect — "It's a different culture, that's how they do it here," — I had heard their bemused and condescending tones when confronted with the reality of daily life in Manila. I knew Dad was the only person in his office who didn't carry a gun and he had to submit to a pat-down search because he didn't check his gun at the entrance. There had never been someone with no gun to check.

My parents laughed about this, while acknowledging that people in the offices downtown did sometimes shoot each other or disappear. This was not America, that was for sure.

Now, in the dark early morning, we Americans all over the city were hearing that our president had been shot. It was unclear to me for a while if he was dead. Nobody would tell me if "assassinated" meant dead or just shot.

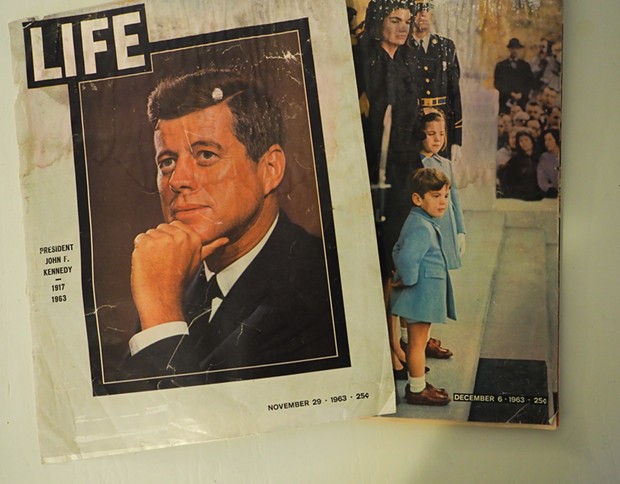

As it happened, Macapagal was safe, Kennedy was dead and we Americans all assembled in our dark, formal attire at the American Cemetery in Manila for a memorial service. Kambing was forgotten in the larger shock and grief.

We all make our own memorials. For the rest of our time in Manila, I looked out the tinted backseat window of the car for the telephone pole I sometimes saw on our way downtown from Bel Air. Scrawled on it was the Tagalog word for goat, kambing. I knew it was unlikely but I thought, maybe, maybe he was buried there. I never asked.

Nancy Short (she/her), former co-owner of Booklegger, still dreams of a world where animals and people are safe.

Speaking of John F. Kennedy, animals

-

Zoo Animal Council Meeting Minutes

Jun 15, 2023 -

Searching for Bertie

Oct 21, 2021 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1