Creative Commons via Wikipedia

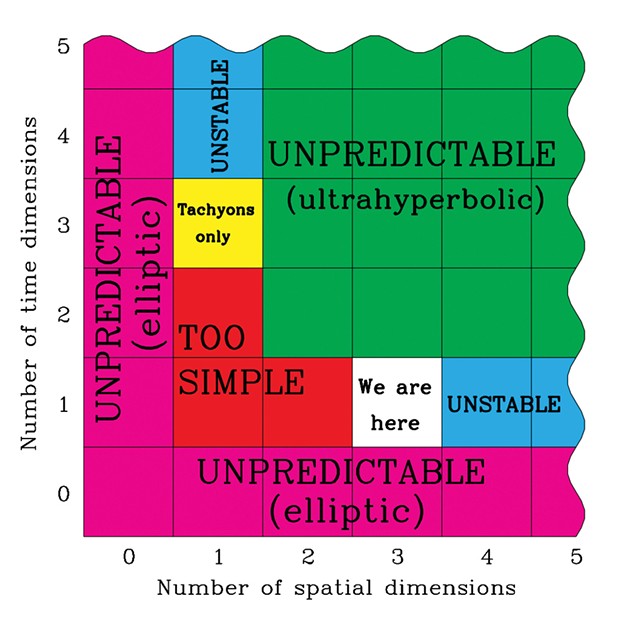

Not only can you mess with the physical constants of our universe, you can also tinker with the number of dimensions of time and space to emphasize, apparently, the unlikelihood of our existence.

[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

"Our Universe has not been fine-tuned for life: life has been fine-tuned to our Universe."

Klaas Landsman, The Challenge Of Chanc

The fine-tuning of many of the "constants of nature" is offered as evidence for both the existence of God and of an infinity of universes beyond our own, aka the multiverse. It's pretty weird both theists and physicists cite the same argument, both looking to support ideas that are neither provable nor scientific. Here, I'll try to show that the fine-tuning argument is spurious and has no bearing on your or my beliefs about God and/or the multiverse.

The constants of nature — there are currently between 19 and 25, depending on whose system you follow — are the foundations upon which everything depends: matter, time, space, life, right down to the existence of intelligent beings who probe them. They include well-known ones, such as the strength of gravity, and arcane ones such as: Plank's constant (the "quantum" of quantum mechanics); the cosmological constant (the energy density of otherwise empty space); and so on. The fine-tuning argument claims values of these constants are really finicky; if they were other than what they actually are, we wouldn't be here. In some cases, neither would the universe. So, goes the argument, either God must have had a hand in creating it all, or our universe — out of an infinity of them — happens to have just the right constants.

Take, for example, the fine-structure constant, upon which the strength of the electromagnetic force depends. It's approximately (not exactly, as was once thought) equal to 1/137. If it were just a tad different, either the element carbon wouldn't be present in the universe or stars (stellar fusion) wouldn't happen, depending on whether you decrease or increase its value. No carbon, no life (probably); no stars, no life (for sure). The same applies to the other constants — adjust them a bit up or down, and atoms won't form or the universe won't survive for more than a few thousand years. In particular, the conditions for life, at least as we know it, won't be present. So the universe itself and our presence in it is really, really unlikely.

Do you see the flaw in this reasoning? How can we know what's likely or unlikely? We have exactly one universe in our sample. To say something is "unlikely," we need to know what "likely" is — presumably by checking a few other universes to see what their constants are, then decide if our universe is likely or not. Theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder likens it to seeing a pencil balanced on its tip — we'd look at it and say, "Wow! What are the odds?" Because we've seen many other pencils lying flat, we know a pencil balanced on its tip is an anomaly. Since we can't observe other universes to be able to say, "Wow!" we can't say anything about the likelihood of our own universe. It's just the way it is.

If you're thinking "anthropic principle" at this point, you're ahead of the game. The principle, in its weak form, says that the universe must be the way it is because we're here to observe it. So — back to fine-tuning — this universe has to have the physical constants necessary to accommodate conscious life, otherwise we wouldn't be here to observe it. (That's known formally as a "logical truism," or, less formally, "Duh!")

Finally, I should mention that there's a wildly speculative, not to say narcissistic, strong form of the anthropic principle that says, in essence, that our being here means that the universe was somehow compelled to produce intelligent life. However, I understand you need to be chemically high to wrap your brain around that one.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]) notes that while the universe may allow for intelligent life, it's hardly optimal — we're here by the skin of our teeth!

Speaking of...

-

Multiverse

Feb 29, 2024 - More »

more from the author

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 2: Problems

- May 2, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 1: Stratfordians vs. anti-Stratfordians

- Apr 25, 2024

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022