[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Several cases involving police use of deadly force have received widespread scrutiny during the last year: the July 17 strangling death of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York; the Aug. 9 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; the April 4 shooting in the back of Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina; and the recent beating death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore.

Eyewitness testimonies, video evidence and street protests have made these deaths into a matter of national outrage. But the overwhelming majority of homicides by police happen with minimal and slanted coverage, and inadequate public accountability.

Take, for example, the case of a young man killed a few months ago in a remote part of Northern California.

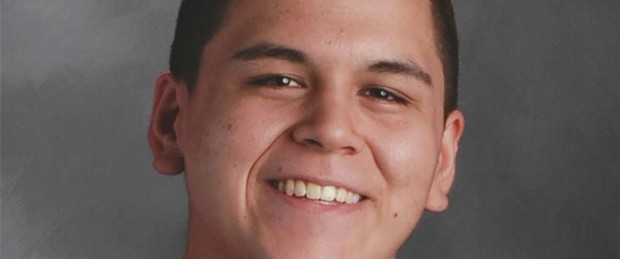

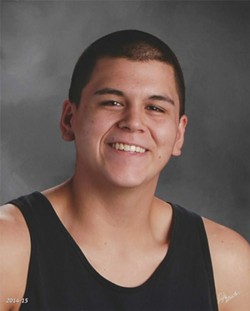

At this point, only one fact has been established: In the middle of the night on Dec. 18, a confrontation took place between 17-year-old Richard Estrada, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe, and California Highway Patrol officer Tim Gray in the small town of Willow Creek, about 50 miles east of Eureka. Estrada died on the spot and Gray was injured.

What happened, how it happened and what led up to the tragedy is not yet known. According to Melva Paris of the Humboldt County Sheriff's legal office, the matter is currently under investigation by Sheriff Mike Downey, whose completed report "will be referred to the Humboldt County District Attorney's Office for review." In 2011-2012, a coalition of regional law enforcement agencies signed off on a protocol for a Critical Incident Response Team (CIRT), to be initiated when an officer is involved in the death of a civilian. The goal of CIRT is to make sure such cases are "fully and fairly investigated," especially when "questions arise about the propriety of a law enforcement agency conducting an investigation wherein one of its own officers is involved."

But before the official investigation was 24 hours old, Estrada had already been tried in the court of public opinion. The day after the shooting, representatives of CHP and the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office talked as though they had all the facts in hand: They told the media that the officer involved had responded to a report of a car crash in Willow Creek. When he tried to help the teenage driver, "there was a sudden, violent attack. Unexpectedly, [Estrada] pulled out a machete." According to CHP Capt. Adam Jager, the young man then assaulted Gray with the weapon. "The officer, fearing for his life, of course, discharged his weapon as he was going down. The officer was able to miraculously maintain his balance, retreat around his patrol car, got into his patrol car, locked the doors, and called for help."

To make his point visibly compelling at the press conference, Jager waved a machete that he claimed was the same size and style as the one used by Estrada.

This neatly packaged narrative — speculation posing as fact — was offered to and gratefully received by the media before investigators even had an opportunity to interview the injured officer.

Press and television coverage of the incident included the terms "reportedly" and "allegedly," but no information was presented from the Estrada family's perspective. Leanne Estrada, Richard's mother, is not cited or quoted, even though, as I discovered, she is readily accessible and wants to talk about her son's death. "There are many hard questions that need to be answered," she told me.

On the evening of Dec. 17, Mrs. Estrada said that she desperately called the tribal police and 911 to report that her severely manic son was missing and a danger to himself. "Did the CHP and Officer Gray receive this information?" she asked. "Did the responding officer ask for back-up and advice about how to handle Richie's situation?"

Meanwhile, headlines and captions told only the police version of the story, portraying Estrada as the perpetrator: "CHP Shoots, Kills Suspect," "Wounded Officer Kills 17 Year Old Attacker," "Officer Involved in Fatal Willow Creek Assault Identified," "California Highway Patrol Officer Attacked By A Man With A Machete."

While we wait for the completion of the official investigation, we should keep in mind that Estrada's homicide was neither an isolated nor unusual incident and that, typically, justice is not served in the aftermath of such tragic encounters.

As President Obama's Task Force on 21st Century Policing recently noted, it is a serious problem that police departments are not currently required to report to the federal government all incidents of "officer-involved shootings." Despite this lack of official accountability, researchers estimate that police in the United States kill about 1,100 people annually, or three people every day. Between Dec. 18, when Estrada died, and May 1, more than 420 people died in confrontations with police.

We also know that, despite the lack of official statistics, the victims of police homicides are usually young, male and disproportionately African American, Latino and Native American. They look like Richard Estrada.

Every study carried out during the last 70 years confirms this conclusion. "In the North, there is as much killings of Negroes by the police" as takes place in the South, observed Gunnar Myrdal in his comprehensive 1944 study of American race relations. Black refugees from Southern violence "do not escape Jim Crow," James Baldwin acerbically noted in 1961, "they merely encounter another, not-less-deadly variety." According to a survey of nine cities in the 1960s, "the rate of Negro victims was seven times that of white victims."

This is not a problem of the distant past. A study of 1,217 fatal police shootings from 2010 to 2012 found young black men are 21 times more likely to be killed than their white peers.

If, as his mother says, Estrada was suffering from a mental illness, this too resonates with what we know about police homicides. The last young Hoopa man to die in a confrontation with police, Peter Stewart in 2007, was suffering from schizophrenia. "His death," his mother Jacqueline Marshall-Alford said, "was a heart-breaking shock to the entire community."

The January 2014 case of Parminder Singh Shergill in Lodi echoes Estrada's situation. When the police tracked down Shergill, a schizophrenic acting erratically and waving a knife, they shot him 14 times. "Being a minority veteran with mental illness in rural America certainly didn't help him," said an advocate for the Shergill family.

The everyday occurrence of police homicides is compounded by the lack of transparency and fairness that characterizes most official post-mortems. In the case of Estrada, for example, the protocol of Humboldt's CIRT, supposedly designed to ensure that his death is "fully and fairly investigated," is not publicly accessible. It took me several requests to Humboldt County Counsel and the sheriff's department to get a copy.

Moreover, if CIRT is supposed to guarantee the appearance of propriety, how is it that the same sheriff's department that was involved in the events surrounding Estrada's death is the lead agency in the investigation? And why is it that, more than four months after Estrada's death, the sheriff's spokesperson "can't provide an estimated date when the investigation will be completed?" Meanwhile, it took less than two weeks for the Maryland state attorney to complete an investigation into the death of Freddie Gray and bring criminal charges against the officers involved.

It is a rare event when an officer is held criminally or professionally accountable for any crime or malfeasance resulting from the death of a civilian. You might expect this in Philadelphia in the 1950s when police officers were vindicated in killing 32 people, of whom 28 were African American. But statistics tell the same story today. A study by criminologist Philip Stinson looking at thousands of "justifiable homicides" voluntarily reported by police departments over the last decade found that only 54 officers were charged with crimes. Of those, 11 were convicted.

Moreover, it has become almost impossible to successfully pursue civil rights claims against police departments because, according to the dean of University of California Irvine's law school, the U. S. Supreme Court puts an unfair burden of proof on petitioners.

"When the police kill or injure innocent people," said Erwin Chemerinsky, "the victims rarely have recourse."

Even as Attorney General Eric Holder spoke out against civil rights abuses by police, his Justice Department resolutely defended individual police officers charged with use of excessive force.

The cover-up and whitewashing of police killings is now so widely recognized that Obama's mainstream task force recommended "policies that mandate the use of external and independent prosecutors in cases of police use of force resulting in death."

I personally don't think this goes far enough, and would like to see politically independent, civilian review boards in charge of investigating serious allegations against the police. But a special prosecutor would be an improvement on current practices, such as those followed in Humboldt County, where law enforcement agencies keep everything in-house and out of sight.

Tony Platt is a Distinguished Affiliated Scholar at the Center for the Study of Law and Society, UC Berkeley Law School. He is the author of 11 books, including Grave Matters: Excavating California's Buried Past (Heyday 2011). Documentation is available from the writer at [email protected].

Have something you want to get off your chest? Think you can help guide and inform public discourse? Then the North Coast Journal wants to hear from you. Contact the Journal at [email protected] to pitch your column ideas.

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8

more from the author

-

Trinidad, Do the Right Thing

- Jan 4, 2018

- More »

Latest in Views

Readers also liked…

-

Hope

- Sep 7, 2023

-

California Says No to Privatizing Medicare

- Sep 21, 2023