The Wall

Cpl. Crystal Landry and the effort to get more women policing Humboldt County

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

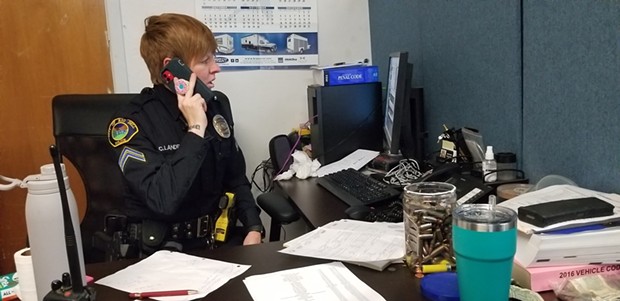

Cpl. Crystal Landry has a cold. It's just a sinus thing, she says, something she picked up from one of the other officers on last week's shift. She blots her nose with a tissue and pecks at the keyboard of her computer, typing a Be On the Lookout for a stolen dirt bike.

"They took it right off the guy's porch in broad daylight," she says. It's Saturday afternoon in Rio Dell, and Landry is looking forward to a busy shift. The sky outside is threatening a late spring rain, with anemic droplets misting the air. Landry blots, types and shifts uncomfortably in her oversized chair. The old computer hums in front of her. On the desk next to her is a repurposed plastic Costco cashew jar full of miscellaneous bullets. The chief, Jeff Conner, is preparing for retirement by cleaning out the evidence locker. Banker boxes full of old files and confiscated detritus are stacked around Landry's desk. She spots a fossilized rat turd and makes a small sound of disgust, cheerfully razzing Conner as he passes through the bullpen.

Blot. Type. Shift. Sniff. Because the dirt bike's owner and a neighbor around the corner had security cameras, Landry has already identified the alleged thief. The cameras gave a good view of his face and that of his female accomplice, as well as the truck and trailer he loaded the bike onto. Within a half-hour of sending stills from the cameras around to other agencies, a colleague at the Eureka Police Department flagged the suspect as a well-known petty criminal. In fact, the EPD officer says they towed the getaway truck just a few weeks prior for lack of license and registration.

The Rio Dell Police Department shares a building with City Hall on Wildwood Avenue, the town's (population 3,400) main drag. The building, like many in Rio Dell, is nestled into the slope of a hill. Because of the evidence locker, the small station smells strongly of cannabis, a smell Landry says she hasn't noticed in years. Landry has short blond hair and bright blue eyes, a quick smile, a blurry tattoo across the back of her right wrist. She graduated from the College of the Redwoods Police Academy in December of 2018, one of only three women in her class, and the only one who remains an officer. She started with RDPD a month later, promoting to corporal in 2021. Landry's goal is to become a detective. She was a stay-at-home parent prior to going into the academy, waiting until her daughter was in pre-school before joining the profession. She likes a fast-paced job, she says, and the Rio Dell police force has that. It's a place where she gets to "do a little bit of everything."

"I like to get to the bottom of things, to work a case from beginning to end," she says. A call comes in with the suspect's most recent addresses. Landry pulls out her phone, which is adorned with a doughnut pop socket, and types them into her navigator. Her cell phone and its voice assistant function is an essential tool for her job, allowing Landry to call contacts and look up information as she drives from call to call.

A few weeks earlier, two teenage boys jumped the fence of the local elementary school and stole an expensive skateboard from an eighth-grade girl. Landry drove from one end of the town to the other while calling contacts using her car's Bluetooth system. Could the principal send her screenshots from the school's security camera? Had the clerk at the Dollar General seen two teenagers come in carrying a yellow skateboard in the last half-hour? She studied the stills of the two boys, watched how they walked through the schoolyard.

"I swear I recognize that one," she muttered. "But no, he's kind of splay-footed. The kid I'm thinking of doesn't walk that way."

Rio Dell's small size (just 2.5 square miles) and Landry's relentless friendliness work to the officer's advantage in property theft cases. There's a lot of foot traffic in Rio Dell, people out on the sidewalks and in their front yards, people who almost universally wave when they see Landry on patrol.

In the schoolyard, a scrum of children gathered around to look at the video and stills. No, they said, they didn't know the boys. Landry drove up and down Wildwood, turning down the side streets and stopping when she saw someone. Seniors walking their dogs. The chief of the local volunteer fire department. A woman in a front yard comforting her bereaved friend.

No, said the woman, and her friend, the seniors and the fire chief, they didn't recognize the boys in the video.

Now, several weeks later, Landry says the case was resolved when a relative marched the suspect down to the station with the skateboard. Things like that happen all the time in Rio Dell, she says. People know one another. Word gets out.

Landry checks in with Conner about going to the alleged dirt bike thief's addresses, all of which are in Eureka. Conner gives her the go-ahead, telling her to give the Eureka Police Department a head's up that she's going to be in their area. Although most police officers in California have broad power to work cases outside of their jurisdiction, leaving city limits to pursue a suspect can be risky. Once they've passed a probationary training period, almost all officers work alone unless they've requested back up. Rio Dell and Ferndale both rely on dispatchers at the Fortuna Police Department to route calls for service, and the three Eel River Valley stations offer mutual aid to one another when necessary. Landry says she also gets backup from the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office, the California Highway Patrol and CalFire.

Each contact Landry makes is punctuated by a fastidious call into dispatch to relay where she is and what she's doing and a second call once the contact is completed. In Eureka, Landry will be relying on the availability of officers in other departments to support her if things go wrong. Conner tells Landry to check in with HCSO dispatch during her trip north, "just in case she gets in trouble." He and the other officer on duty will hold things down while she's gone.

"Don't get in trouble," he adds as she leaves.

Landry's vehicle smells vaguely animal. Last week she broke up a fight and took two assailants into custody — a pair of dogs that had been attacking a neighborhood goat. Although Rio Dell has a dedicated community service officer who also does animal control, Landry and other officers pinch hit these duties during the CSO's off hours. Landry and her fellow officers also serve as administrative staff much of the time. When there's no one at the station, walk-ins are instructed to call the phone number on the locked door. This routes to the Fortuna dispatch, which calls whoever's on patrol back to the station. On one recent shift, Landry ping-ponged between the station and a call to a suspicious death, taking custody of an abandoned cat, driving to a local home to examine a dead body, then back to the station to retrieve another cat. According to Conner's staff reports to the city, RDPD responded to 50 animal-related calls for service between April 2 and June 20. The city has an agreement with Miranda's Rescue Animal Shelter to take in stray dogs and cats; the department is stocked with humane traps, bags of dog food, cans of cat food. Landry has rehomed at least two kittens herself; one went with her, the other to a cousin. But not every animal call is heart-warming.

"I was never scared of dogs before I started this job," she says, pulling out of the station. "Something about the uniform freaks them out."

Landry gets on the highway and heads north, dabbing occasionally at her runny nose. She knows Eureka well, she says. She grew up in the area, bouncing from house to house in a chaotic childhood. Some of her family members were and are using drugs. Some were and are on the other side of the law. Landry recalls visiting a notorious apartment building with a group of friends when she was a teenager, someone flicking on a light realizing there were cockroaches everywhere. She jumped on a boy's back, screaming.

"I hate bugs," Landry says, shaking her head.

Her experiences as a child informed her choice to become a cop, she says. She wants to help people, to be there when they're ready to make a crucial decision, to turn their lives around. Like many people in her profession, she is frustrated with recent changes to the California criminal justice system that have reduced sentencing options for low-level drug offenders and other misdemeanor charges. Many of her arrestees bounce out of jail within hours. Landry sees arrests as an intervention, a consequence, and jail as a chance for some people to disrupt their pattern of recidivism.

"I arrest people for charges weekly," she says. "They never help them. Why are we arresting them if they aren't keeping them?"

Landry pulls into the first address, a small battered house in the Pine Hill neighborhood. She calls into dispatch and gives her location. The front yard is stuffed with the rusty carcass of an old fishing boat. The pipe and wire fence has several "Beware of Dog," signs on it. Landry looks around warily then opens the gate. She knocks on the door, which has a paper with a list of hand-written rules duct-taped to it: No visitors after 7 p.m.; Don't come here looking for my daughter. Inside, a dog barks. After several knocks Landry gives up. She gets back into the car and radios back to HCSO, calling in all-clear.

According to the 30x30 Initiative, a coalition working to increase the number of women in policing, women make up only 12 percent of sworn officers and 3 percent of leadership positions in the United States. These statistics play out similarly in Humboldt County. Women make up four of 38 sworn officer positions at the Eureka Police Department (10 percent); two of 19 at the Fortuna Police Department (11 percent); four of 22 at the Arcata Police Department (18 percent); seven of 110 deputy sheriffs (6 percent) and 22 of 88 correctional officers (25 percent) at HCSO.

Fortuna Chief Casey Day says that while he is always looking to diversify the make-up of his staff, he says more men are attracted to the field than women.

"Traditionally, it was more of a male-occupied profession," says Day. "I've worked for different agencies. It's always been, at least in my experience, that departments are made up mostly of males."

Mike Perkins, director of the College of the Redwoods' Public Safety Training Center, says he has seen female cadets generally struggle with some of the physical requirements of the training, which include tasks such as scaling a 6-foot wall and a 165 pound "body drag," and is interested in offering a specialized unit of women in policing that would help cadets develop proper technique, as well as prepare them to enter a highly male-dominated field. A similar unit was offered at Perkins' previous post in Santa Barbara. The ability to bring it to Humboldt, he says, is hampered by the same factors impacting his program and the profession overall: recruitment and retention. The academy does not retain a dedicated teaching staff but relies on local officers to teach units and has had an increasingly hard time finding instructors due to a decline in regional staffing levels.

"The struggle that we're facing is the fact that we've seen such a shift out of law enforcement, so many people are retiring and we're not really able to backfill those positions," he says. "There's just a lack of interest in going into the profession. Most agencies around the area are very understaffed. What that results in is officers are working overtime shifts ... and that's our main source of instructors."

The average class size has shrunk over the past two years as well, Perkins says, from 20 down to 13.

Greg Allen, who succeeded Conner as chief of the Rio Dell police in July, attributes the decline in enrollment to a number of factors, including COVID but also a nationwide change in attitude toward policing as a profession. Allen taught at the academy for 10 years, and served as a lieutenant with HCSO and several other agencies for a combined 28 years of experience in law enforcement.

"When you talk about recruiting in general, this is not a countywide problem, it's a nationwide problem," he says, adding that high profile use-of force incidents have tarnished the public image of the profession. "A lot of people are staying away from law enforcement. It's a dangerous profession. The younger generation wants flexible hours and guaranteed time off to spend with their families."

Allen was referring to incidents such as the murder of George Floyd in 2020 by police officers in Minneapolis. Local agencies have also weathered scandals. In 2021, the Sacramento Bee revealed that several officers in an EPD unit were active on a group text exchange that included derogatory and sexist language directed at homeless people, mentally ill people and women, including some of their female colleagues.

Allen adds that many trained officers get recruited away from smaller departments by bonuses and higher pay offered to lateral transfers in other agencies and regions. Compensating for this attrition by recruiting new officers is not easy. While almost all cadets currently being recruited into the academy have jobs waiting for them by their recruiting agency, the wait time between finding the right person for the job and getting that cadet onto a beat can be as long as a year when taking into account the six months of academy training, the 10 to 18 weeks of field training and the intense background check, which can take anywhere from 60 days to six months to complete. These background checks for any criminal history or drug use also often include interviews with former coworkers, roommates and family members. For this reason, the average age of a recruit can skew a bit younger, toward people who haven't had a chance to get a DUI or bounce a check yet.

As for the low numbers of women in the ranks, Allen says in his time with the academy the ratio has always been about 70-30. Allen says women bring important strengths to the profession, including being less likely to use excessive force, and having better de-escalation, interpersonal and communication skills. As to why there aren't more of them, the chief says it's down to a number of factors, mostly culture.

"It's been a male-dominated field," Allen says. "The decisions are being made by males. Law enforcement hasn't been an attractive profession to females. I think the men who hold positions of greater power and influence ... they can get things put into action in terms of recruiting women."

Leadership statistics in local law enforcement also follow national trends. Of 277 sworn officer positions combined between APD, HCSO, FPD and EPD, 12 women are ranked as lieutenants, detectives, corporals or sergeants, or about 4.33 percent. Correctional deputies make up the majority of these positions, eight out of 12. Support staff, including dispatchers and administration, also skews heavily female in most departments. In Eureka, Amber Cosetti is the first woman in the department to hold the rank of senior detective and was recently elected by her colleagues to serves as the first female president of the Eureka Police Officers Association.

Like Perkins, Allen also references that 6-foot wooden wall, saying it's an example of physical requirements for the job that may be outdated. (Landry, who was an avid CrossFit devotee prior to joining the academy, says clearing it is more technique than strength.)

"That's one a lot of academies are looking at whether or not to continue," says Allen. "Traditionally men have more upper body strength, but is it realistic to the job we do? You can ask an officer: 'When's the last time you jumped a wall?'"

Landry's promotion to corporal comes with extra responsibilities. On her days off she receives calls from other officers to authorize high-speed pursuits or to drive down for extra help. She's also working on an associate degree in police science through College of the Redwoods. She tries to keep up with the latest technology and practices, training in red dot sighting for her handgun and victim witness interviews.

The 30x30 Initiative reports that under-representation of women in policing "undermines public safety.

"Research shows women officers use less force and less excessive force," 30x30's mission statement reads, noting they also "are named in fewer complaints and lawsuits; are perceived by communities as being more honest and compassionate; see better outcomes for crime victims, especially in sexual assault cases; and make fewer discretionary arrests."

Landry, for her part, has never had to use any of the weaponry included in the 35 pounds of gear she straps to her waist at the beginning of every shift.

"Even if I have to arrest someone, I try to maintain the rapport," she says. "I don't want to go down to their level. You will have more cooperation being kind to them than being an a-hole. And that comes naturally to me. Even if someone is on drugs or whatever, I still think of my work as a service to them."

The next stop is the McCullens Motel, a cluster of one-room cabins on McCullens Avenue in Eureka that are often rented long-term. The motel gained some infamy in 2016, when Maxx Robison, then 20, opened fire there after a drug deal gone wrong, killing 19-year-old Rihanna Skye McKenzie. Robison was sentenced to 24 years in jail. The motel remains a hot spot for drug activity. It's raining as Landry pulls up in front of the manager's office. In a lighted doorway, a trio of young men are blowing cigarette smoke into the wind. They look momentarily nervous at Landry's arrival but then crane their necks in interest, perhaps curious who she's looking for.

Landry rings the doorbell of the manager's office, waits in the rain, then finally spots a sign in the window and calls the phone number listed. A middle-aged woman in sweatpants and a Crabs Baseball shirt comes to the door. She looks unsurprised to see the uniform. Hearing the name of the man Landry is looking for, she gives a dry guffaw.

"That little fucker isn't here, 'scuse my language," she says. "Not on a dare."

The manager asks what her former tenant's been accused of. Told that it's theft, she shakes her head sardonically. The group of young men in the cabin next door have dissolved inside.

Landry leaves and goes to the next address, a modest and clean craftsman on A Street, although she doesn't expect to find the alleged thief there. No one answers the door. The rain picks up, then slackens to a dull drizzle. A call comes in as she gets back in the car. A friend from the academy who's with the sheriff's office recognized the suspect from Landry's BOLO. He's recovered some stolen property connected with the alleged thief out at a house in Field's Landing. Landry takes down the address, then radios into dispatch. Leaving A Street, en route to Field's Landing, there's a new kind of energy about this call, the tantalizing promise of a solid lead.

"It takes a lot to get my adrenaline going anymore," admits Landry. When she was new on the job, her blood would start pumping when she got a report of a hairy situation, a weapon drawn, a domestic violence situation, but now: "I'm getting adrenaline less and less. I get adrenaline on the ride there, but most of the time when I get there it's not as bad as it seems."

She takes the turnoff for Field's Landing, drives down a rugged little street, slowing, looking for the house number. Then:

"I can't believe it," she says. "That's the truck."

The black lifted truck is sitting in the driveway. The trailer isn't there, however, nor is the stolen bike. Landry radios into HCSO then waits impatiently for them to confirm she'll have backup if she needs it. The small house is weathered, its porch leaning slightly. The fenced front yard is littered with trash. A battered trailer sits in the driveway. The rising wind causes a blanket covering one of the trailer's broken windows to ripple and wave. Landry starts there, knocking on the side of the trailer. Nobody answers. She goes to the door of the house and knocks. An elderly woman opens the door, releasing a small pack of large dogs. They are barking but friendly, weaving around Landry's legs. A middle-aged man, possibly her son, appears in the doorway, as well. Landry introduces herself and asks if the owner of the truck is there.

"Is who?" the woman asks. She gives Landry permission to look around the yard and behind the house for the dirt bike or the truck's owner. Landry does, picking her way through the trash. A package of meat is spoiling on top of an old oil drum. No bike. No suspect. Landry goes back to the front door, where a young woman is now waiting, procured from the back of the house by her grandmother. She has long dark hair and tattoos and is wearing a tank top. One leg of her sweatpants is pulled up to reveal an intense poison oak rash. She scratches at it as Landry explains the situation.

"I know you," Landry says. "You were in the video we got, from the security camera. Is that your boyfriend?"

The girl, clearly upset, insists that her boyfriend was just taking back a bike he'd already paid for.

"Explain to me what he thought about the bike," Landry asks as the girl scratches furiously at her rash.

"He put a lot of money into it, $100,000, he tried to do it right," the girl insists. But someone sold it to the guy in Rio Dell even though it didn't belong to them. She'll get him to bring it back.

Landry nods. The girl can't tell her where her boyfriend and the bike are now. She gives the girl her phone number, says to have her boyfriend call her. The girl agrees. Landry gets back in her car, then realizes she didn't get the interaction on her body camera. She nudges it to life, then goes back to the porch and secures the promise from the girl again. The rain is coming down harder now, whipping stinging little blasts in the wind.

Landry drives south, back to Rio Dell. She tries to pay a visit to the man whose bike was stolen, but he's not home. He, too, has a list of rules in front of his door, written on a whiteboard: Don't visit without calling; I don't have time to work on your car; Don't knock on the door, I can't hear you.

She tries calling him. No answer.

Landry returns to the station and begins working on her report. The owner of the bike calls back, finally. He's on his way back to Eureka, he says. The kid who stole the bike is freaked out that the cops are involved and he's going to meet him and give it back.

"Do you want to press charges?" Landry asks. No, he says, he just wants his property back.

Landry blots her nose once again and begins to type up her report. Like most local police departments, Rio Dell has struggled to find and retain officers, many of whom are attracted to a better rate of pay at other agencies after their probationary period is over. Landry says she prefers the "low drama" atmosphere of RDPD. She gets along with her coworkers, they get along with her. That counts for a lot. Also, she feels supported by the community. Last year she had to arrest a combative suspect and several citizens stepped in to help. She didn't need the help, she insists, but was glad to know they had her back. Conner, who worked in local law enforcement since the '90s, says diversifying recruitment and hiring practices are crucial to improving the profession. While the average recruit is young and male, he'd much rather hire someone in their 30s or 40s, he says, someone with more life experience and patience. He and the older cops he knows have changed their approach to a lot of things, Conner says, becoming better at de-escalation because they "don't want to roll around on the ground anymore."

"Crystal is the future of the Rio Dell Police Department," he later adds in an email.

Her report finished, Landry gets back in her vehicle and comes to the assist of an officer making a traffic stop on U.S. Highway 101 just north of Scotia. The driver, who's been popped for drugs before, is known to Landry. He was pulled over for a traffic violation and is now being cited for driving with a suspended license. As the other officer searches the car, Landry talks to the guy. What's he doing now, is he working? She gives him a pep talk.

"It's a great time to get a job," she says. "Lots of places are hiring. Lots of opportunities out there."

Linda Stansberry (she/her) is a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @LCStansberry.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

-

Graduation Day: A Fortuna Teacher Celebrates with her First Grade Class

- Jul 18, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023