|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ARTBEAT

June 29, 2006

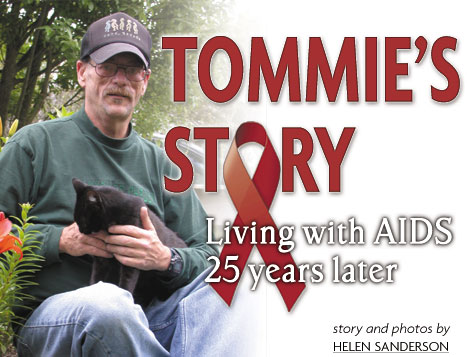

TOMMIE OFFORD ENJOYS GARDENING, YOU CAN TELL. His Arcata yard is small -- about 25 feet across -- and it is literally brimming with flowers. The petals, mainly pinks and purples, some reds and whites, peek over the fence, radiating atop vibrant green stalks that sway a little in the breeze, stirring their sweet smell in the air. Tommie, a middle-aged smoker with a distinct paunch offset strangely by lanky arms and legs, surveys the scene. He refuses to take much credit for the loamy botanical landscape he nurses. The way he sees it, the flowers' survival is not up to him. "My logic is: `I just give you the basics. You determine whether you live or die,'" he says, looking over a tall, 3-month-old dahlia standing solo in the corner of his yard. It wasn't until Tommie almost died 11 years ago that he took those words to heart and decided to live. He picks up a pile of weeds and drops them in a bin, dusts off his hands and carefully climbs the front porch stairs. A sleek black cat skitters past his white sneakers and into the house. Tommie seems especially focused on each step. His pace is steady but not slow. He moves quickly, almost as if he were traversing a balance beam that threatened to deceive his feet. Another kitty, an old fluffy one, watches the procession, but remains lying in the grass. Stepping inside Tommie's home is like experiencing Dorothy's trek to Oz in reverse, trading a Technicolor landscape for black and white. The house is neat, but the furniture is drab and old. The brown carpet is clean, outdated and scruffy. Other than a vase of lilies and a crinkled picture of James Dean hanging by the door, those blue eyes sullenly skyward, there's not much special to the interior of this place. When you live off of $800 a month, and $550 goes toward rent, there's not much left for décor. After food, utilities, laundry and $60 to get the lawn mowed twice a month, Tommie saves any extra pennies -- literally, pennies -- for lily bulbs. Fortunately, his medication and doctors' visits are covered through MediCare and MediCal. As Tommie eases himself into a worn chair draped with an afghan, he mentions that the cats are probably his most constant source of friendship. He can't help but worry about what will happen to them if he dies. Now that he's settled, he's ready to talk about his life. He says he never would have done this five years ago, but there's no use hiding anymore. Tommie Offord has lived with AIDS for more than 25 years. He is 49. He never thought he would live this long. Tommie told his family he was gay when he was 23 years old. "Coming out as gay was nothing because I fell in love," he says. "I wrote a love letter to him and sent a copy to everyone in my family and said, `If you don't accept it, bye!'" Tommie talks about his childhood detachedly. He is the youngest of eight kids -- some of them were "horrible," he says without elaborating further. Some of them are dead now and that doesn't upset him much. He bounced from different towns in Oregon to Trinity County, where he lived with a foster mother. At 8 years old he started smoking, and was up to two packs daily by 13. Before he graduated high school he tried every drug besides heroin. His youth was not ideal, to say the least, but if it bothers him he doesn't show it. "It toughened me up for life," he says. "I think that's why I'm still here." By the time he turned 24, in 1980, Tommie was definitely living on the wild side. He had just moved to Fresno, a conservative Central Valley town without much of a gay scene. "It was kind of like Eureka is now," he explains. "There was maybe one bar that had a gay night once a week." However limited the community, Tommie immersed himself in it. It was the height of the gay rights movement, and people were celebrating. He partied, used meth on occasion and had sex with lots of different men. Then, in late 1980, he went to the doctor with what he assumed was a bad case of "jock itch." He discovered he had second-stage syphilis, which was treatable, and a fatal form of pneumonia called GRID -- Gay-Related Immune Deficiency. Tommie was told he had about three months to live. The doctor asked him to make a list of his sexual contacts so they could come in for testing. There were eight people on the list, though there were more men he'd been with than that. He couldn't remember their names. He left the doctor's office in a daze. "Then I just got me a fifth, a half gallon of liquor, shut my apartment door and screamed and yelled at the walls for three days," he says. He didn't know how else to deal with it. Humboldt County Public Health Nurse Geoff Barrett explains that the moment when someone is told they are HIV-positive, it's not the ideal time to educate them about their condition, nor rattle off a list of medical and social services available to them. "Their mind kind of goes blank at that time," Barrett says. "So I try to give them, on a piece of paper, one referral. I try to give them the emotional support that I can. They have as much of my day as they want. I also try to ascertain what their support system is, and encourage them to make use of that support system -- whether it be a close friend, a close relative, a partner, a spiritual guider and any or all of the above. I also want to get contact information from them and their permission to call later and make sure that they're OK." When Tommie was diagnosed so little was known about the disease that -- as he puts it -- "there was really nothing to do about it." He confided in his roommate, who then confided in his friends. The word spread. Everyone at the bar knew within a week. Some of them, Tommie said, whispered behind his back. Others offered their sympathy, with a pat on the shoulder, saying they were sorry he was going to die. He didn't tell many people after that. It wasn't until eight years later, in 1988, that he told one of his sisters. This month marks the 25th anniversary of the U.S. Center for Disease Control's first diagnoses of AIDS among a few men in Los Angeles. Known as Gay-Related Immune Deficiency until 1982, now some 45 million men, women and children worldwide have AIDS; 25 million have already died from it. AIDS has surpassed malaria and tuberculosis as the top microbial killer. It's transmitted through blood or bodily fluids sexually and intravenously. It's decimating poor South African countries. It is not just a gay disease. It is not just an IV drug user's disease. An estimated 8,000 people die daily from AIDS, mostly in the developing world. There are antiretroviral medicines also known as "drug cocktails" that can prolong an infected person's lifetime by decades. But there is no cure. We know this stuff. We learn about it in sex ed at school, at the doctor's office, through national media. But what do we know about the status of AIDS in our own back yard? According to the most recent records, 225 people in Humboldt County have been diagnosed with AIDS since 1985: 191 men, 30 women and four children. But that tally doesn't reflect the number of AIDS patients actually residing on the North Coast. A person diagnosed outside of the county is not included in local statistics, even if they've lived here for years. Others test positive in Humboldt, then move away. And the number doesn't reveal how many AIDS patients are living. More than half of them have died -- 136 people. Gone. Also, the AIDS statistics do not include people living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. There is a separate report for that. As of June 6, 87 people -- 65 men and 22 women -- had tested positive without yet developing symptoms. These statistics date back only four years, when HIV "surveillance reporting" began in Humboldt County in July of 2002. Taken together, 312 people have been diagnosed with AIDS/HIV here in the past 21 years. Geoff Barrett, who maintains the county's records on HIV and AIDS, estimates that 180 to 200 infected people are actually residing in Humboldt County today. Peggy Falk was one of the founders of the North Coast AIDS Project (NorCAP) in 1985. That year -- the same year actor Rock Hudson died of AIDS -- the county received a $20,000, one-year grant to start an education and awareness program. There was a lot of work to be done. Falk recalled that at the time people believed AIDS was casually contagious, spread from telephones or toilet seats. Meanwhile nurses and paramedics were still lax about wearing rubber gloves when treating bleeding patients. This is not to mention the way AIDS was treated on the political level nationally. President Ronald Reagan did not use the word "AIDS" publicly until 1987. One of his close supporters, Rev. Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority, called AIDS the "wrath of God upon homosexuals." Falk is now the deputy director of the Humboldt County Public Health Branch. She comes off as vigilantly unemotional. She answers questions with facts, not anecdotes. She doesn't babble, she doesn't elaborate. She calls NorCAP "highly effective, highly respected." She lists the volunteers that helped the program along -- among them many members of the gay community, Open Door Health Center, Hospice of Humboldt, therapists, attorneys, the American Cancer Society. Some volunteers visited dying patients' homes just to give them a haircut or talk. Within a few years NorCAP had over 100 volunteers. Could she tell a story about one of her former clients, perhaps something that illustrates what it means to live on the North Coast with AIDS? "We built this program," Falk said in a phone interview, "with many, many people who were living with the virus and a lot of those people are not here anymore. So I don't feel comfortable taking one person's story..." She stopped then and inhaled sharply. "Excuse me. It's hard sometimes. There are a lot of people who put a lot of effort into this and if I pick one person's story it diminishes the other people's stories." Through the 1980s Tommie moved around, working as a blackjack and roulette dealer in Reno and as a bartender in Sacramento. His condition didn't keep him from partying and, generally, his health was finethough many ofhis old friends had died. In 1990, a friend who was in the later stages of AIDS said he was leaving Sacramento for Eureka to be closer to family. Tommie decided to head north too, and be a caretaker for his friend, Carl. It wasn't an easy job. Carl was self-destructive. He would stay high on meth and drunk for days. His friend's health was deteriorating fast. When it was clear he was nearing the end, his family -- who did not accept the fact that he was bisexual -- took Carl in. He died a day later. Tommie imagines they gave him too much morphine. It was probably the humane decision, he said, better than letting him suffer any longer. Tommie joined the family for the funeral. They took a boat from King Salmon and scattered Carl's ashes in the waters off the South Spit. There was a small obituary in the newspaper, but of course it didn't mention why he died. "That's all there was to it," Tommie says with a shrug. "I never thought that would be me." In its previous capacity,

Scott Mitc Mitchell is the program coordinator for the North Coast AIDS Project. He's been in this office, at the public health department, for three years. Before that he was in another office across the hall. This office, he said, is far better. "Now I have a window," he says, gesturing to a sliver of barred glass offering a spare view of a grassy courtyard. Right: North Coast AIDS Project Mitchell has been with NorCAP since 1991, working his way up, so to speak, from a volunteer in the "Buddy Program," which offers social and emotional support for people with HIV/AIDS, then as a part-time health educator and eventually to the top spot. When the program began in 1985, Peggy Falk was the only paid employee. Now NorCAP has a staff of 10, working in both prevention and medical case management for HIV-positive residents. Funding amounts to a few hundred thousand dollars (exact figures were not available) from a number of county, state and federal grants, including the Ryan White fund, named for a 13-year-old hemophiliac with AIDS who was denied entry into his public school in Indiana in 1985. He died in 1990. And while NorCAP is far bigger and better financed than before, funding for prevention efforts has been scaled back. NorCAP's biggest prevention grant was recently slashed by 60 percent. That's not unique to Humboldt County, Mitchell says, it's happening across the state. Meanwhile, federal funding for the program on a whole has remained "flat" for years. Meanwhile, client loads increase along with costs of services. That translates to reduced funds. A year and a half ago one staff member was laid off as a result. NorCAP serves 140 clients. Mainly they're from the Humboldt Bay region, Arcata and Eureka. But NorCAP brings their van to the outskirts of the county weekly, to places like Orick, the Hoopa Valley and to Southern Humboldt. They offer HIV testing, condoms, bleach kits for sterilizing needles and prevention information. But not everyone living with HIV wants to be part of the program. "Some people don't want it known that they are infected with HIV," Mitchell says. "There may be some people who go out of the county for services because of the confidentiality concern. However, you should understand that confidentiality is the name of the game. We don't refer to patients by name within our own staff, we use code numbers." Tommie has gotten help from NorCAP over the years and was also a part of its Buddy Program. But lately, he says, "I generally just deal with things myself." After his friend's death, Tommie says he continued to live like he was invincible. But in 1995 the party stopped. He was diagnosed with a fatal neurological disorder called Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy, PML, and everything changed. The opportunistic infection usually affects cancer and AIDS patients with compromised immune systems by creating lesions on the brain. Patients with PML typically die within nine months. Three lesions formed on Tommie's brain. He lived. However, the disease brought him to "ground zero." All basic tasks like walking, talking, writing and eating had to be re-learned. He still can't run or sing, he says. His balance is bad. He can walk only at one rate of speed, so he avoids crowds, like the Farmers' Market, where people constantly stop and start. Bowling is a thing of the past, too. He was semi-pro before. He also gave up driving. Today, he feels about 80 percent "normal," and he says it is as good as he will get. That means he's essentially homebound, with dwindling energy, balance problems and severe diarrhea. Dr. Lee Leer is Tommie's primary physician. He says that he has other patients who've lived with AIDS almost as long, more than 20 years. For those who have been on medication long-term a common side effect is called lipodystrophy. "It's a change in the way the body metabolizing fat," he explains. "They lose the fat in their face, for instance. Their legs and arms get scrawny, and for unknown reasons it will re-distribute elsewhere in the body. You'll often see people with a big tummy." Tommie doesn't look like a person with a grave disease. Though he is gangly, exactly in the way Dr. Leer described, he doesn't look frail. He's not perfectly mobile, but he gets around OK. Still, one of the things that most brings him down is his appeareance. The drugs have dramatically altered him. He used to be cute -- a nine out of 10, he says. At his job in Reno, looks opened doors. The more attractive you were, the better the job you could get. He got good jobs. Now, he knows, he wouldn't qualify. Below: Tommie's medication.

That meant quitting speed, and taking his meds religiously -- four pills a day, five pills every other day. In the late '90s he took 48 pills every day. Tommie also manages his money scrupulously. He still smokes cigarettes, but has cut back to less than a pack a day. He's also been celibate since 1995 -- partly because of his looks, he says, but mainly because he could never forgive himself if he accidentally infected someone. He moved to Arcata seven years ago. His landlady seems to like what he's done with the yard, because she hasn't raised his rent. Mainly he passes the time watching TV, playing cribbage with a friend or poker on the computer, or chatting online with other gay people with HIV. And of course, he gardens. Tommie points to the purple dahlia that stands alone in the corner. It was just about dead when he first brought it home three months ago. An employee at Longs Drugs gave it to him for free. "For the first two months I wondered if it would make it," he said. "But it just kept living." COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ARTBEAT

Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

hell's

seven- by nine-foot office was a jail cell for juvenile delinquents.

It's a claustrophobic space with mint green walls, a desk, two

chairs, a book shelf and precious little room for anything else.

hell's

seven- by nine-foot office was a jail cell for juvenile delinquents.

It's a claustrophobic space with mint green walls, a desk, two

chairs, a book shelf and precious little room for anything else. Still, he doesn't regret getting PML, even

though it nearly killed him. It was a wake-up call. He explains

that it forced him to become ultra-vigilant about his health.

"I basically had to make a decision," he says. "Whether

to live or give up and die."

Still, he doesn't regret getting PML, even

though it nearly killed him. It was a wake-up call. He explains

that it forced him to become ultra-vigilant about his health.

"I basically had to make a decision," he says. "Whether

to live or give up and die."