COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ARTBEAT

TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

June 29, 2006

5 Questions for Ray Raphael

by HANK SIMS

ACCLAIMED SOUTHERN HUMBOLDT HISTORIAN Ray

Raphael (left) doesn't really have anything against the

Fathers (though he doesn't much care for the term). What he objects

to is the central role they have assumed in the teaching of American

history. In his recent work, Raphael has gone back to original

documents to show that the impetus for American Independence

came not from a few heroic leaders, but from the great masses

of the incipient nation's citizenry. ACCLAIMED SOUTHERN HUMBOLDT HISTORIAN Ray

Raphael (left) doesn't really have anything against the

Fathers (though he doesn't much care for the term). What he objects

to is the central role they have assumed in the teaching of American

history. In his recent work, Raphael has gone back to original

documents to show that the impetus for American Independence

came not from a few heroic leaders, but from the great masses

of the incipient nation's citizenry.

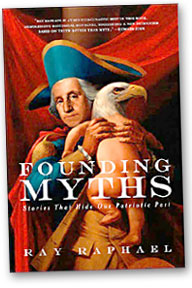

The paperback version of Raphael's latest book

-- Founding Myths: The Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past

-- will be released on July 4. In it, he argues that the

"great man" theory of the Revolution, with its adulatory,

larger-than-life portraits of figures like George Washington,

Thomas Jefferson and the rest, is an invention of the 19th century,

a time when the new country was in need of heroes. Unfortunately,

he says, the great men have overstayed their welcome. Most Americans

still think of the Revolution in terms of their actions. They

miss out on the truly revolutionary aspect of the country's origins,

and therefore fail to understand its powerful lesson -- that

millions of people together were able to invent their own form

of government.

Founding Myths recounts a number of stories

that have worked their way into the American psyche --  Paul

Revere's mission to warn Massachusetts farmers of an impending

invasion, the signing of the Declaration of Independence -- and

shows how the actual history is richer, more complex and more

inspiring that the common story would have it. Paul

Revere's mission to warn Massachusetts farmers of an impending

invasion, the signing of the Declaration of Independence -- and

shows how the actual history is richer, more complex and more

inspiring that the common story would have it.

1. I discovered in your book something I didn't

know before -- that the Fourth of July is kind of a sham. Nothing

that important happened on that day during the Continental Congress.

But does that matter?

It doesn't really matter. There is something to

celebrate, and what there is to celebrate is Independence.

The way we celebrate it, it's as if one man, Thomas

Jefferson, a genius, dreamed up Independence. He wrote up this

document and everybody voted for it and signed it, and that's

what we're celebrating. That's the standard story, and what we're

celebrating is the Declaration of Independence -- the actual

document.

What we should celebrate is Independence, not the

Declaration of Independence. Independence was a huge step, but

it wasn't dreamed up by one man -- Independence was the climax

of a six-month-long national discussion such as the country has

never seen since. In every tavern, and in every meeting house,

whenever people met, throughout the land, people were discussing

whether to take the big step and go for Independence. They debated

and debated and discussed it. They started passing resolutions

at the state and local level, saying yes, it's time to go for

Independence. We know of at least 90 of these documents.

Congress itself was hovering. There weren't enough

votes -- there wasn't a clear majority one way or the other.

And of course they needed an overwhelming majority for this thing

to work. So rather than vote on it prematurely and have a split

vote, the people who were in favor of it said, "Let's let

these local bodies exert more influence" -- sort of send

it back to the people. So, for instance, in Maryland, which was

opposed to it, all the patriots got together, put together a

state convention and reversed their Congressional delegation.

Enough of those came through so that finally, those

who were in favor of Independence, said, "O.K., now we're

ready for the vote." And they did vote -- on July 2. On

the second, they vote for Independence. That was the big vote.

But one of the things they did when they were considering

it, they said, "Well, if we're going to do this, we have

to have a document explaining it." So they appointed a committee

to write that document, and Thomas Jefferson wrote the main part

of the draft. And that's the document we've sort of enshrined

as scripture. But the thing is, that was kind of the rationalization.

It wasn't until July 4 that they actually approved the final

draft of the Declaration. That's where July 4 comes in. But Independence

itself dates from the 2nd. That was the grand event.

But then they started thinking, "We should

make a big deal of this." So they sent to have a fancy copy

of it made, and that was ready on August 2. The delegates who

were there started to sign it. Many of the delegates who signed

it -- I think 14 of them -- weren't even present on July 4. Many

of them weren't even Congressmen on July 4. But they signed it

anyway. And they kept signing it through the fall. One of them

didn't sign it until the next year. Meanwhile, this document

has taken on a life of its own.

We create these scenes -- the signing of the Declaration

of Independence, where everyone is lining up and signing their

name on July 4. And we have this great mythology develop.

There's a very humorous story. There's this guy,

Samuel Chase from Maryland. We know that he was in Maryland on

July 2, and we know he was in Maryland on July 5. And yet he

signed the Declaration! Now, in truth, this is not a startling

thing, since nobody signed it until August 2. But everybody convinced

themselves that everybody signed it on July 4, so this myth arose

-- that he was so pumped up about Independence that he rode 100

miles through the night just to sign the document on the Fourth,

and then rode home. All these old history books have this great

patriotic story about Samuel Chase, riding through the night.

2. This is the nut of your argument, I think.

In turning our past into stories, and to personify it in certain

great characters, we end up losing touch with our actual history.

Right. And the distortions can be misleading, they

can be derogatory, they can be dangerous. And the use of story

moves us forward to right now. Karl Rove has mastered the art

of the story, and the need for story, and is able to develop

very clean, very clear stories that people want to hear, and

that are totally bogus. It doesn't matter whether they're true.

Saddam is connected to 9/11 -- because he lives

in the same part of the world, and there's a bunch of Muslims

over there. The story works for his purpose. There's not a shred

of evidence for it, but half of the American public believed

it years later, and a third of Americans still believe it. And

look at the harm that story did, and was intended to do.

Stories are invented as tools. In the crudest sense,

they're propaganda tools. And in that sense, the better the story

-- user beware.

3. But stories, also, are unavoidable. Humans

have a sort of innate need for stories to make sense of the world.

You yourself are a storyteller, are you not?

Humans use stories to make sense of the world.

And you can do this responsibly, or you can do this as a means

of grabbing power. From the beginning of time, people who have

sought power have created stories about how they are linked to

God. And they've used these stories to assume power. And they're

still doing it today. Religious fundamentalists in both the Christian

world and the Islamic world are using the story that they are

linked to God to seize power -- to seize crude political and

military power. So you have to beware of that story.

A responsible use of the story is to look at history,

to try to understand how human beings behave and then to boil

it down in a way that makes sense, and makes it interesting and

appealing and kind of gets at the heart of the matter.

Let me give you an example. Instead of the Paul

Revere ride -- which is the story we've kind of developed --

there is an earlier, alternate story about these farmers. The

farmers in Massachusetts come together. For 150 years, they've

come together in their town meetings and they could vote on their

own. Suddenly, they're told they can't do this. And they come

together in every tavern and every meeting house, and they say,

with one voice, they say, "No way. We're not going to do

this. We're going to shut down the government that does this

to us."

And so they stage these marvelous popular demonstrations,

which are more than just demonstrations -- they're actually acts

of overthrow. In the town of Worcester, 4,622 militiamen -- that's

half the adult male population of the entire county of Worcester

-- come together in one town, in one moment. They line both sides

of Main Street, and they get the British-appointed officials

to walk the gauntlet between them, their hats in their hand,

reciting their resignations, saying, "I will not uphold

this British authority. This does not speak for the people."

Now, that's a good story.

4. Except for the fact that it doesn't have

a protagonist.

It doesn't have a protagonist, and that's one big

reason why that story hasn't been told. We like our protagonists.

I'm actually addressing this in my next book. In my next book

-- it's called Founders: The People Who Brought You A Nation

-- I'm retelling the whole founding of the nation with specific

protagonists. but the protagonists are chosen more responsibly,

to reflect a whole cross-section of the American public rather

than just a handful of elite men.

Within this, one of my protagonists is a man named

Timothy Bigelow, who was a blacksmith in Worcester, in this town,

in this story I just told. He was very involved in this group

process. The people met at his home, and he was the representative

to the provincial congress. When the people were ready to declare

their independence, they gave him very specific instructions.

So I can tell this story using Timothy Bigelow as a protagonist,

but I don't have Timothy Bigelow being the motive force of this

entire revolution. That's the irresponsible use of the story.

History, by definition, is a group process. And

the way we tell history, in stories -- we reduce that group process

to a series of individual actions. That distorts history. It's

meant to be empowering -- look at all the impact an individual

can have! -- but in fact it's very disempowering, because we

all know we don't have that kind of power. The only way to achieve

any kind of power is to work together. If we understood real

history, we'd be much better able to seize the reins and to effect

change.

5. How could the Fourth of July be celebrated

in a way that would better reflect the actual history of the

nation?

Well, hey! Fireworks? Take your cooler to the river

and have a good time?

The civic-ness of the holiday has sort of disappeared

into the pleasure of the holiday. Basically, the Fourth of July

has become the midsummer festival. It's gone beyond its nationalism

to a much more general celebration of midsummer. And actually,

that's great. All cultures, throughout history, have figured

out ways to celebrate the middle of summer. l

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ARTBEAT

TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write

a letter!

© Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|