|

COVER

STORY| IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER October 13, 2005

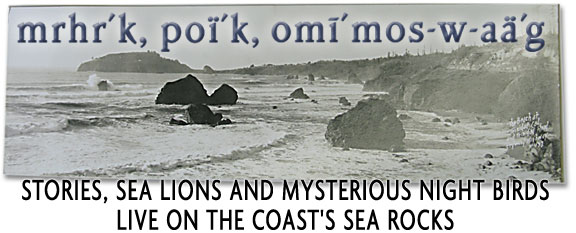

by HEIDI WALTERS Above: View of sea stacks near Trinidad. Humboldt County photograph collection, HSU Library

This is a story about a bunch of rocks. Now, some people would have you believe these particular rocks --- sea stacks, islands and jabby pinnacles out there in the Pacific, mostly visible from shore --- are meaningless, without life or value. They sit there all day, seemingly doing not a damned thing, while the ocean crashes, splashes and rolls all about them. So immobile are these rocks that you can sit on a little bench overlooking Trinidad Bay and compare what you see now to a photo taken in 1920 by A.W. Ericson, or to a sketch made in 1851 by Gold Rush chronicler J.Goldsborough Bruff, and see how nothing has changed. Camel Rock, at the south end of Trinidad Bay, still looks like a huge camel kneeling down in the water as if to let a passenger on. Pilot Rock, that lopsided triangle south of Trinidad Head in the open ocean, likewise remains much the same, alerting boats and ships they're close to land (either gently by day by being visible, or roughly at night by collision), as it has done for centuries. Walk around to the north a bit and you'll find there's still a grove of Sitka spruce on top of Pewetole Island and, in winter weather, water spraying through its blowhole. Green Rock, north of Elk Point, looks white as ever in the drier months (bird poop) and then, once the rains start, turns green with invigorated plants. And Flatiron's still flat.

Left: Sea stack near Trinidad Bay, sketched by J. Goldsborough Bruff in 1851 An oceanic plate dove under an opposing tectonic plate, volcanoes erupted, lava oozed into the trough where the plates mashed to join mud, sand and gravel tumbling in from the continent, mixing with materials scraped off by the merging plates; shiny red and green cherts developed from tiny water critters' exoskeletons, chunks of volcanics broke off and rode in from a thousand miles away and crushing and pressure deformed the whole lot --- it was a mess, and it became the massive Franciscan Formation, a mélange that underlies much of California. The ocean rose and fell hundreds of feet while the formation uplifted, and younger sediments settled on top. Then, much more recently (83,000 years ago), the ocean cut terraces in the up-rising formation, upon which marine sediments accumulated, and on top of that surface is where the Yurok town of Tsurai ("mountain"), now called Trinidad, developed. The sea stacks out in Trinidad

Bay and elsewhere along the coast are part of the mélange:

Some are chert, some sandstone, some greenstone and basalts.

They have an action-packed past. Even so, perhaps you're inclined

to agree with the Times-Standard, which opined on Sept.

18, 2005, whinging about $700,000 "state officials"

(actually, it was the feds) allocated for a management plan for

the California Coastal National Monument: "It seems a little

extravagant to spend that much to manage, well, a bunch of offshore

rocks." Cheers, hoist one for blustery observations. But such dismissal is blunt-headed, says Rick Hanks, the Bureau of Land Management's manager of the CCNM. "They're not just a bunch of rocks," says Hanks. "That's just like Reagan saying, 'If you've seen one redwood, you've seen them all.' They're vital in the protection of California's fragile coastal ecosystem. The thing that folks don't fully realize is, everything's connected to something. If we start to move in on habitat that other species are using along the coast, as our population grows and their habitat disappears, these rocks become sanctuaries. Sea lions, for example: They need a place to rest, to haul out. And both the brown pelican and the cormorant fish. They use a lot of energy to do that. They have to rest. If they're being disturbed all the time and are flying from place to place, they wear out. You ever wonder why harbor seals are lounging around? They're not being `lazy.' They use a lot of energy feeding themselves, and they need to rest. And these rocks provide the opportunity for them to rest undisturbed." As HSU biology professor Rick Golightly puts it, "Some people think they're nothing but a sea stack, but to seabirds they're everything. Seabirds are important, if you want to look at it strictly from an anthropocentric viewpoint. We can watch the seabirds, and see how they're doing, what their production is, and that tells us what the ocean's doing. It's where they're getting their food, and so they're indicators of the health of the ocean." Mad River Biologists founder and seabird researcher Ron LeValley, who helped shape the biological portion of the CCNM management plan and will continue to work on it, says fishing is generally good around sea rocks where seabirds roost and nest because there's a concentration of nutrients there. But unlike many other places that have been designated national monuments, the value of these sea rocks has "mostly been ignored," says Hanks. That is, except by hunters and fishermen of old, who realized the value of pinniped skins and seabird eggs. In the 19th century, traders plundered seabird colonies for eggs and slaughtered seals in droves for their furs, and many species disappeared from the coast. While seabirds and marine mammals are protected now, their habitat is increasingly limited to the offshore rocks because of human development on the shore. The CCNM aims to protect those last refuges. Dispelling ignorance is one way to achieve that protection, and a main goal of the CCNM, for which the final management plan was released in September. The national monument, designated by President Clinton on Jan. 11, 2000, encompasses more than 20,000 sea rocks and small islands under BLM jurisdiction along 1,100 miles of California coast and out 12 nautical miles. The monument only covers the portions of these rocks that are above mean high tide, although the BLM notes there are important tidepools connected to many of the rocky tops. The water between the rocks is not part of the monument, and some rocks are left out --- those privately owned or otherwise appropriated, for lighthouses or military purposes, for instance, or those protected under other types of management such as the Farallon Islands, near San Francisco, and Castle Rock near Crescent City, both important seabird rookeries. The rocks in the monument range from a bit more than 10 acres to as small as "the size of your computer," says Hanks. The monument designation creates a forum for land and wildlife managers --- especially state fish and game and the state parks and recreation departments, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service --- up and down the coast, along with academic researchers, local governments and others, to combine their knowledge of the sea rocks and foster more research, promote education and better protect the rocks and their inhabitants. Acting as "gateways," select local communities will be stewards, lending "local flavor" to each portion of the monument. The Cher-Ae Heights Community of the Trinidad Rancheria played an integral role in the plan's development and will act as a steward for Trinidad's rocks. Hanks notes that the national monument designation doesn't affect natural gas and oil leases, although such threats to sea life on the rocks would have to be weighed. Nor does it interfere with fishing --- that had been a concern at first among fishing groups, but Hanks says they've since come on board. (He adds that the "extravagant" money was used to pay consultants from Jones & Stokes to write the plan, which took three years --- "pretty cheap for a plan," says Hanks.)

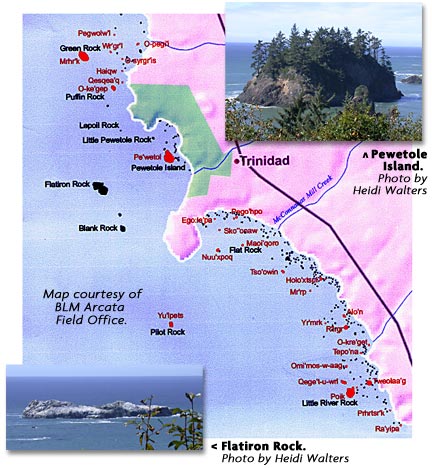

For fun, CCNM manager Hanks decided to rank the rock clusters along the entire California coast according to their combined biological, cultural, geological and scenic values. He gave the jumble of wild rocks jutting out of the ocean around Trinidad the highest rating. "Not only is there a variety of shapes and sizes of rocks, but some have fairly significant seabird colonies, and sea lions use these rocks. They also are highly visible from Trinidad Head with the trail around it." It also helps that there's an academic influence with HSU's Telonicher Marine Lab in Trinidad, says Hanks. Most compellingly, every rock has a Yurok name and sometimes a story. In 1920, anthropologist T.T. Waterman catalogued these rocks and stories, as well as inland features, in his book Yurok Geography. "Hupa his rock" is one entry, for a rock in Trinidad harbor near the mouth of Luffenholtz Creek. Last week, on a calm clear morning,

two kayaks pushed off from the little port in Trinidad where

Yurok dugouts, then ships carrying conquerors, explorers, hunters,

gold diggers and lumber barons, and now modern-day fishing boats

have launched and returned. The kayaks made a long, slow loop

through the bay, headed toward Camel Rock (poï´k,

a "nighthawk," in Left: Common Murre.

Photo by Ron LeValley.

Other seals swam amid the watery field of bull kelp, or balanced on their bellies on small rocks. "Look at that one, she looks like a ballerina," said Wick about one seal improbably draped over a tiny rock, resting, her tail tipped up. The vigilant seal finally dropped back as the kayaks negotiated a narrow passage between a cluster of mostly submerged rocks. On a taller sea stack farther off stood two black oyster catchers, their long orange legs and orange beaks bright against the dark rock. On an even taller rock, a cormorant stretched tall, likely working a fish down into its belly before it could dive back in the water. Gulls hovered about, looking for opportunities, and once a kingfisher alighted on a close-by sea stack before leaping away again into the air. In myth the kingfisher, or Halcyon bird, calms the sea when it is nesting because it builds its nest on the water. The real kingfisher does no such thing --- but the sea that day was calm. Farther out sat a large sea

stack called Prisoner's Rock (nuu´xpoq, for "double,"

in Yurok), where folklore has it that the Trinidad community

in the 1880s stored its drunks overnight. Cavity-nesting birds,

such as the storm-petrel, nest there. Way out beyond the head

is Pilot Rock (yu´Lpets, meaning "white").

According to a story told by the late Axel Lindgren, of Tsurai

and Swedish descent, in his Sept. 26, 1995 Tsurai-Trinidad Trails

column in the Trinidad News & Views, "the remoteness

of Pilot Rock from the beaches, other rocks and the exposure

to the Pacific storms, presented a daring challenge to male Indians

of Tsurai on which to test their strength, courage and bravery

against nature." Left: "Leon on the beach," a postcard from Trinidad, 1913. Humboldt County photograph collection, HSU Library. Very close to shore, in the surf, the kayaks passed near Little Trinidad Head (kr´nit-w-o´'oL, "Chicken Hawk"). A small rock near it, covered with cormorants, is called kr´nit-we´yots-o-lep. It means "Chicken-hawk his boat where it-lies." Later that day, up on the ground looking down at the bay, long-time Trinidad resident and local historian Ned Simmons cryptically related the tale, as he's heard it, of Little Trinidad Head and the rock nearby. "Peregrine Falcon lives there --- [the Yurok] call him Chicken Hawk [kr´nit]. That's where he lived until he killed those pelicans. And then he had to leave the community, and he went up to Sugarloaf by Somes Bar. When he left he overturned his canoe, and that's that rock where all the cormorants are." Waterman's version doesn't mention the pelicans, but it does say that "Ocean was this hero's wife. She was always talking and muttering, the Indians say; `and she is that way even yet.'"

Simmons walked down to Trinidad State Beach and pointed toward Pewetole Island. The Sitka spruce growing on top of the bedded-sandstone islet are the southernmost occurrence of that species of tree on coastal rocks. It also has a blowhole. "One time I watched a spout come up and rainbow, then dissipate like angel clothes," Simmons said. He pointed to Flatiron Rock, a flat-terraced rock directly out to sea from the state beach. It's often covered in California sea lions. "The crab fishermen will sit up there, at the parking lot on 'Chicken Point,' to see how the waves are hitting Flatiron," Simmons says. Then they'll decide who "isn't too chicken to go out." Far to the north of Trinidad beach, just past Elk Head Point, lies Green Rock, mrhr´k in Yurok. Waterman's book doesn't give a Yurok story for Green Rock, but that doesn't mean there isn't one. And today it and Flatiron are two of the most important rocks for nesting seabirds, says Ron LeValley of Mad River Biologists. "Green Rock, in the summertime, it's got a cap of black and white, which is the common murres. That's where they'll nest." A murre lays one pale-green egg on a rocky ledge. The egg is pointed at one end and round at the other, so that if it rolls it moves in a circle this keeps it from rolling off the cliff. Both parents incubate the egg. Parents will fly hundreds of kilometers and "may dive as deep as 100 meters for food" for their chicks, according to the United States Geological Survey's website. The USGS describes most poetically how the chicks, who finish growing up in the water, leave their birthplace: "One of the most beautiful parts of our field season is when the murre chicks leave the nest. At dusk in late August murre fathers congregate on the water below the colonies and call up to their chicks in anxious voices. Soon the chicks begin answering with their shrill calls, and the little downy birds start raining down into the water."

Right: Sea stack near Trinidad Bay, sketched by J. Goldsborough Bruff in 1851 Pellagic cormorants also use Green Rock, as well as pigeon guillemots (who nest on the steep rock face in crevices, and feed on a little fish called a moss-head warbonnet), tufted puffins, the rhinoceros auklet and possibly the Cassin's auklet. The nocturnal fork-tailed storm-petrels nest on Green Rock, and on Camel Rock which is their southernmost known nesting locale, says LeValley. The storm-petrel nests in crevices of natural cavities in the rock, "underground, out of the reach of marauding gulls." "The reason these rocks are so important," says LeValley, "is these seabirds are adapted to spending a lot of time at sea. But, with the exception of the Halcyon, a mythical bird that nests on the water, they have to come to land at some point because it's the only place they can lay their eggs." Because the birds spend so much time on the wing or water, they're awkward on land and so wouldn't be able to get away easily from predators such as foxes or raccoons. So, they use the sea rocks, and either crowd shoulder to shoulder, like the cormorants (who do build nests) and murres, to protect their young or, like the storm-petrel, hide their eggs in underground burrows to protect them from gulls while they're away feeding. The storm-petrel may fly 40 miles out to sea early in the morning and spend all day skimming the water for plankton and krill. "They hover, or kind of walk on the water," says LeValley. "That's why they're called `St. Peter.'" The petrel, which unlike other birds has a strong sense of smell, returns at night, in the fog, to its burrow to feed its chicks a musky oil that it has converted its catch into. If you travel north of Green Rock by land, you'll come to Patrick's Point --- su´mig in Yurok, the much celebrated "abode of the last immortals," writes Waterman. "Although these beings left the other parts of Yurok territory when the Indians came into existence, they still linger on here. I think the most important of them are the Porpoises, who are still considered as people, not as animals." A modern tale is told of how archaeologists exploring Cone Rock (ye´ktsin), south of the point, found a thousand sea lion skulls with two-inch holes bored through their tops. Speculation is that, similar to practices among Arctic people, the skulls were left as offerings to the immortals at su´mig for a good hunt. The stories stretch farther, and the birds and mammals too, up to the rocks clustered around the mouth of the Klamath, and several miles into the ocean where Reading Rock (also "Redding") lies. But we'll leave them be, now. Well, maybe just one more:

Does that convince you that a rock isn't just a rock? As local poet Jerry Martien wrote in the first poem of his book The Rocks Along the Coast:

COVER

STORY| IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

So,

at first glance, there's nothing much to report about those boring

old rocks, other than they're sure pretty on a postcard or the

cover of your Black Phone Book. To see the rocks in action, you'd

have to go back about a million years or so then fast-forward

(and invite along HSU geology professor Ken Aalto for interpretation).

So,

at first glance, there's nothing much to report about those boring

old rocks, other than they're sure pretty on a postcard or the

cover of your Black Phone Book. To see the rocks in action, you'd

have to go back about a million years or so then fast-forward

(and invite along HSU geology professor Ken Aalto for interpretation).

Yurok, perhaps

named for the nocturnal storm-petrels that nest there). On the

way back, a harbor seal began trailing one of them. This was

after the kayaks had cut a wide berth around a flat rock crowded

with jittery sea lions, and after they'd spied a porpoise diving

through the water to seaward.

Yurok, perhaps

named for the nocturnal storm-petrels that nest there). On the

way back, a harbor seal began trailing one of them. This was

after the kayaks had cut a wide berth around a flat rock crowded

with jittery sea lions, and after they'd spied a porpoise diving

through the water to seaward. Now

and then the seal swam forward to pop up beside the kayak for

a better look. Its dark, wide-set eyes were hard to read before

it ducked back under. Bob Wick, paddling the kayak, noted aloud

that "they are territorial." Wick, a planner

with the Arcata office of the BLM, is the local coordinator for

the CCNM. Wick explained protocol: Never get too close to rocks

with seabirds or mammals on them --- they're either resting or breeding,

and disturbing them can be disastrous. The Marine Mammal Protection

Act dictates that if your presence alters the behavior of a marine

mammal, you need to back off. And CCNM director Hanks says seabirds

such as the common murres are especially sensitive. "If

one takes off they all take off. A kayak could come out and scare

them, and the whole colony's production for that year could be

wiped out in minutes by gulls. Gulls also come and eat the chicks,

too."

Now

and then the seal swam forward to pop up beside the kayak for

a better look. Its dark, wide-set eyes were hard to read before

it ducked back under. Bob Wick, paddling the kayak, noted aloud

that "they are territorial." Wick, a planner

with the Arcata office of the BLM, is the local coordinator for

the CCNM. Wick explained protocol: Never get too close to rocks

with seabirds or mammals on them --- they're either resting or breeding,

and disturbing them can be disastrous. The Marine Mammal Protection

Act dictates that if your presence alters the behavior of a marine

mammal, you need to back off. And CCNM director Hanks says seabirds

such as the common murres are especially sensitive. "If

one takes off they all take off. A kayak could come out and scare

them, and the whole colony's production for that year could be

wiped out in minutes by gulls. Gulls also come and eat the chicks,

too." After

"many months of pre-training," the men "would

swim from the beach to Pilot and climb upon the rock... the task

was to remain overnight and swim home in the morning." Tales

of sea serpents and giant octopuses dragging people into the

deeps surround Pilot Rock, which was also a good place to collect

mussels.

After

"many months of pre-training," the men "would

swim from the beach to Pilot and climb upon the rock... the task

was to remain overnight and swim home in the morning." Tales

of sea serpents and giant octopuses dragging people into the

deeps surround Pilot Rock, which was also a good place to collect

mussels. Locals

report being able to watch the murres fledging from the coastal

cliffs. And, on another rock in the CCNM where common murres

nest, Devil's Slide off San Mateo, biologists have set up monitoring

video cameras to observe the birds up close. Thousands of murres

used to nest on Devils' Slide, until a combination of drowning

by gill net and a 1986 oil spill killed them. Biologists set

decoys up to draw the murres back, and it worked. This time of

year, the murres are gone, but there are plenty of preening cormorants

and pelicans to watch: www.fws.gov/sfbayrefuges/murre/murrehome.htm.

Locals

report being able to watch the murres fledging from the coastal

cliffs. And, on another rock in the CCNM where common murres

nest, Devil's Slide off San Mateo, biologists have set up monitoring

video cameras to observe the birds up close. Thousands of murres

used to nest on Devils' Slide, until a combination of drowning

by gill net and a 1986 oil spill killed them. Biologists set

decoys up to draw the murres back, and it worked. This time of

year, the murres are gone, but there are plenty of preening cormorants

and pelicans to watch: www.fws.gov/sfbayrefuges/murre/murrehome.htm.