|

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | OFF THE PAVEMENT | ARTBEAT November 9, 2006

by HELEN SANDERSON I DON'T WANT TO GO,"

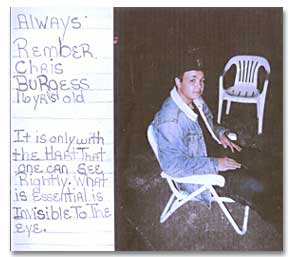

he said. Christopher Burgess (right) -- ward of the court, drop-out, 16 years old, 5 feet 11 inches, 170 pounds and brown-skinned -- was trapped at the bottom of a brush-filled gulch off of Chester Street in Eureka. In his pockets were a dollar bill, breath spray and a small baggie of pot. Meth was in his blood. Pepper spray was on his skin. His belt, which did little to hold up his shorts, was fixed with a knife scabbard. Less than 10 feet away was his would-be captor, 30-year-old Eureka Police Officer Terry Liles, wearing a bullet proof vest. It was a Monday afternoon, Oct. 23, around 2 o'clock. School was letting out at Washington Elementary across the way. Burgess and his girlfriend, Angel Omstead, were watching The Benchwarmers at a family friend's home when county probation officers walked through the open door to apprehend him on a warrant. (Authorities will not say what he did to violate his probation, or what he was on probation for.) Burgess is alleged to have then pulled a hunting knife -- 10 inches from handle to tip -- on the officers. They Maced him but he still managed to back them out of the house at knife point before taking off on foot through neighbors' yards and down into the gully. Probation officers called for back-up, saying they were in pursuit of a male subject with a knife -- they didn't mention his age or name. An off-duty sheriff's deputy, who was picking up his/her child from school saw the commotion and joined the chase.

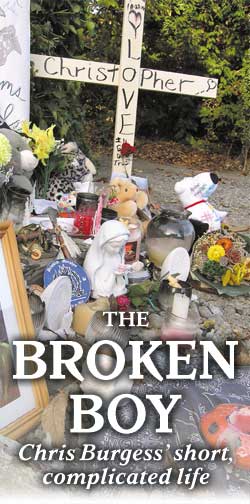

Minutes later, Christopher Burgess was dying. The first bullet had gone through his heart and lodged in his spine. The second entered his hip and came to rest in his abdomen. Liles and other officers carried Burgess to the street. An ambulance brought him to the hospital, just blocks away. He was pronounced dead at 2:39 p.m. An investigation by the county's Critical Incident Response Team has been ongoing since the shooting and is not expected to be completed for at least two more weeks. In the meantime, the community is left wondering whether Christopher Burgess' death -- the second EPD-involved fatal shooting in six months -- was really justified, as has been implied by Eureka Police Chief Dave Douglas, and also what circumstances would lead a teenager to choose such a dangerous path. In a nutshell, Margorie Burgess, who has grieved very publicly at candlelight vigils, protests and City Hall meetings, says that her son simply "wanted to be free." He was locked up constantly from a young age. When he fell in love with a girl he decided he wouldn't go back to an institutionalized life, even though he had less than one month of his probation to serve out. "Teenagers make mistakes," she said, "but they don't need to have dire consequences."

John Smith was Chris Burgess' fifth grade teacher at the Eureka Academy, a now defunct alternative school for students grades four through six with behavioral problems. Chris was recommended for the Academy by teachers and administration at Grant Elementary after he caused too many problems there.

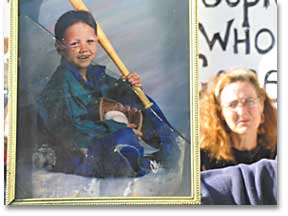

Left: A childhood portrait of Burgess at the courthouse protest. Photo by Helen Sanderson. Smith, a tall, lanky man who has to duck his head to enter his office, sat down at the Transition Opportunity Program School one afternoon last week to talk about Chris. He described him as a kid who was very nice and funny but who also had a temper. And when he got angry he would make bad decisions. Smith remembered the day that Chris first got into serious trouble at the Academy. "As I recall, we were in the gymnasium, and he asked to go to the bathroom, and he never made it back," he said. While he was away, it turned out, Chris had pulled a knife on some high schoolers. "The high school kids disarmed him and took him to the office of Zoe Barnum," Smith said. "They thought it was kind of a joke. What was he doing? He was only a fifth grader, and he was a very small fifth grader."

Eventually, Chris was brought back to the Academy because, as Smith put it, "that is where expelled kids go." And generally, Smith said, Chris had many good experiences at school including a three-day camping and canoing trip at Camp Ravencliff in Southern Humboldt. He worked with Blue Ox Millworks to build a schooner. He also taught English on the Zoe Barnum campus to foreign language-speaking adults, something Smith said he liked a lot. Chris also became close with a pre-law student mentor from Humboldt State and with Eureka Police Officer Mike Johnson, who came to the school often to shoot hoops and read with the students. But Chris' temper tantrums never ceased, and Smith said he never understood the source of the boy's anger. "My work with him was to try to get him more involved in positive things," he said. "He was a young kid that just wasn't successful in traditional schools. We did what we could to try to mitigate that." Vicki Holsworth, a retired Zoe Barnum resource specialist, also remembered Chris, even though he was not a student of hers.

Holsworth and Chris forged a relationship after that. He would stop by to see her on occasion and she took a special interest in him, even offering to help pay for his tae kwon do lessons if he got good reports from his teacher and his mother. According to Holsworth, Chris was a smart kid and academics weren't his problem, it was his behavior. "So I asked him, `What do you like to do? What do you do well?'" Holsworth recalled. "And most of the time, for a little guy like that they don't know. But he gave me probably five answers, clear as a bell. He liked to go fishing, he liked camping, he liked working on the nature trail over at Grant -- that was one of the first things they'd take away from him for misbehaving, and they wouldn't allow him to go out for weeks at a time." Chris later invited Holsworth to his weekend tae kwon do match. But he never showed up. She found out later he got in trouble again and had gone to juvenile hall. Above: Chris Burgess in a recent photo. Courtesy of the Burgess family.

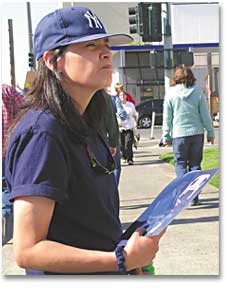

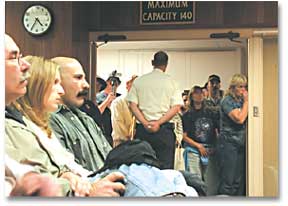

Left: Phenicia Martinez, Chris Burgess' godmother, at the courthouse protest Oct. 27. Photo by Helen Sanderson. Chris' mother, Margorie Burgess, said Chris was in foster homes from Fortuna to Manila. "They pulled him away from me," she said one recent evening on the porch of her parents' Eureka home. "Apparently I wasn't good enough for them." Caring for Chris and his younger brothers was never easy. Chris' father, a man of Hawaiian descent, died in San Francisco before Chris was born, Margorie Burgess said -- not that he was likely to have been part of his life anyway. Over the years she worked as a prep cook at the Ingomar Club in Eureka. "I was the first person in my family in years to get off of welfare," she said. The trade-off was spending less time parenting her children. Chris bounced between foster homes -- at least one of which he ran away from -- to juvenile hall, to the Regional Facility/New Horizons in Eureka for minors with substance abuse and mental health issues, to Homes of Refuge, a group home for juveniles who habitually commit "status offenses" such as running away and curfew violations, or even misdemeanors and felonies. He was also sent to a center in Ukiah, where Margorie said he escaped and hitchhiked home. "If I wasn't in court I was meeting with probation officers," she said of her days off of work. And when Chris would run away she would think she spotted him everywhere she went. "Everybody had his head," she said. On one occasion, Homes of Refuge released Chris without calling her first to make sure her living situation was squared away. As it happened, the timing was very bad. She was staying in a tent in her parents' backyard when Chris showed up toting garbage bags full of his stuff. Margorie Burgess said her son never caused serious trouble but continued to "run amok." He wasn't dealing drugs or stealing. He'd break windows in an abandoned warehouse, skip school, run away, play with matches. She didn't know how to control him. "Officers kept telling me, `Just keep getting him cited and it will work out,'" she said. She took their advice but now regrets it. "I had faith in the county and look at what I got."

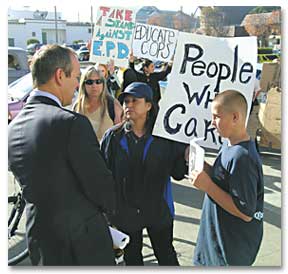

One foster care employee, who asked to remain anonymous, said that typically the county will not remove children from their parents' custody unless there is an immediate threat to the child's health and safety. "A lot has to go down for these kids to be taken away," he said. Left: Margorie Burgess, left, and Angel Omstead listen to DA Paul Gallegos' prepared statement regarding the officer-involved shooting. Photo by Helen Sanderson. A juvenile hall employee, also speaking on the condition of anonymity, said Margorie visited Chris very rarely. Once, she said, Margorie showed up drunk and started a fight with his godmother, Phenicia Martinez, and was not allowed back. "Chris and his mom didn't get along," the employee said. But Margorie has maintained that Chris was very affectionate with her. When she visited him, she said he would sit in her lap and cry and hug and kiss her even though he was too old to be acting that way. And when it was time for her to leave, he was the last kid in the hall. He was "squawking," she said -- "I love you, mom," over and over as she walked out the door. "They wanted to put him on depression pills because he kept crying all the time," she said. "I told them no. He didn't need pills, he needed me."

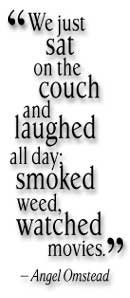

Right: DA Paul Gallegos' listens to protestors. Photo by Helen Sanderson. Two weeks ago, the girl that Chris had fallen in love with -- Angel Omstead, 16 -- sat on the C Street curb across from the Eureka Police station, wearing jeans and a baggy red windbreaker. A crowd had gathered with signs -- "Murderers in uniform are murderers no less,"; "EPD killing spree: Who's next?"; "It's not OK to shoot a child." Omstead held a badly misspelled sign by her feet without enthusiasm that declared to passersby that the police killed her boyfriend. She remembered him as "funny, caring, hella helpful, respectful," and always trying to put a smile on someone's face. "We just sat on the couch and laughed all day; smoked weed, watched movies," she said of their time together. She said things were looking up for Chris. He was holding down his job at Burger King. She said she recently got him to stop using methamphetamine. On the day he was shot, though, he did have speed in his system, as toxicology reports later revealed.

Since the shooting, she said, her days have felt almost like a dream, like she'd just wake up and Chris would be there again. Now that she might be pregnant -- she's not sure, since she hasn't been to a doctor yet -- that hazy sense of limbo has only been accentuated. Before Chris was killed they discussed the possibility of having a kid. "It's what Chris wanted," she said. Right: Margorie Burgess at a town hall meeting Oct. 30. Photo by Helen Sanderson. The vigils, she said, are helping her cope, and also giving her hope that the police will be found to have been in the wrong in his death. "There is no way me nor his family are going to let this shit get slid under the rug," she said. "Chris will be fucking known." In the meantime, Martinez is having trouble adjusting to life without her godson. "I'm pretty much distraught," she said. She's been sleeping in his bed, and thought she heard him call her nickname -- "Phooch" -- the night before. She misses fishing with him "eight days a week" down by the Adorni Center and the Del Norte Street dock, and said that she'll always remember him as "a nature boy."

A few nights later, on the porch of her parents' house, Margorie Burgess recalled how every time her son came back to her, he would only talk about memories from when he was 10, or younger -- the times when he was still at home, when they were still a family, the days before her son got caught up in the system. Traffic roared by through the rain as she sat on the stoop, smoking a cigarette. "Ten to 16 is a lifetime," she said. "He had no life." COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | OFF THE PAVEMENT | ARTBEAT Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Officer Liles arrived, located

Burgess, yelled to him to give up and made his way into the steep

ravine.

Officer Liles arrived, located

Burgess, yelled to him to give up and made his way into the steep

ravine.

It was

at the Academy, though, that Chris paved his way into the juvenile

justice system.

It was

at the Academy, though, that Chris paved his way into the juvenile

justice system. It turned out -- "unfortunately,"

Smith said -- that the knife Chris had had a locking blade, making

it a more serious weapon than a simple pocket knife. The police

were called, Chris was expelled and sent to juvenile hall. A

short time later he wound up in foster care. (Before then he

lived down the street from Zoe Barnum in a housing project with

his mother.)

It turned out -- "unfortunately,"

Smith said -- that the knife Chris had had a locking blade, making

it a more serious weapon than a simple pocket knife. The police

were called, Chris was expelled and sent to juvenile hall. A

short time later he wound up in foster care. (Before then he

lived down the street from Zoe Barnum in a housing project with

his mother.) "Chris made himself

known even at our school," she said. "The first time

I actually saw him he was on his bike. He was going to park it,

and an older student was trying to take his bike. The little

guy was not going to back down, and he was going to get trashed

over it. So I got the bigger student to move along and Chris

kind of thanked me for my help."

"Chris made himself

known even at our school," she said. "The first time

I actually saw him he was on his bike. He was going to park it,

and an older student was trying to take his bike. The little

guy was not going to back down, and he was going to get trashed

over it. So I got the bigger student to move along and Chris

kind of thanked me for my help."

After

his first run-in with the juvenile justice system in Humboldt

County, Chris Burgess spent a lot of time in group homes, foster

homes and other types of institutional care. As with Chris' encounters

with the police, though, it's difficult to precisely trace his

life through the system. In both cases, officials either cannot

or will not discuss Chris' experiences, citing laws designed

to protect the privacy of children.

After

his first run-in with the juvenile justice system in Humboldt

County, Chris Burgess spent a lot of time in group homes, foster

homes and other types of institutional care. As with Chris' encounters

with the police, though, it's difficult to precisely trace his

life through the system. In both cases, officials either cannot

or will not discuss Chris' experiences, citing laws designed

to protect the privacy of children. At

the same time, though, her very public, critical stance has plucked

some nerves among some people in the community who got to know

Chris -- and Margorie -- through the child's travails within

the criminal justice system.

At

the same time, though, her very public, critical stance has plucked

some nerves among some people in the community who got to know

Chris -- and Margorie -- through the child's travails within

the criminal justice system.

About

a month before he died, Chris had fallen in love. He was staying

with his godmother, Phenicia Martinez at the time, as the court

had ordered. He was supposed to adhere to a 7 p.m. curfew. One

night about a month before the shooting, Chris came home and

told Martinez a girl had asked him on a date. Could he go? She

told him no -- he didn't have much longer to serve and he should

just cool out. The next day he gathered his stuff and left.

About

a month before he died, Chris had fallen in love. He was staying

with his godmother, Phenicia Martinez at the time, as the court

had ordered. He was supposed to adhere to a 7 p.m. curfew. One

night about a month before the shooting, Chris came home and

told Martinez a girl had asked him on a date. Could he go? She

told him no -- he didn't have much longer to serve and he should

just cool out. The next day he gathered his stuff and left. Judging

by the amount of meth found in his blood, he certainly must have

been feeling its effects as he pulled the knife on the probation

officers. After Chris backed the officers out of the house, it's

Omstead's contention that he dropped the knife. (Police said

they found the knife at the scene.) She said she saw him use

both hands to hike up his shorts when he started to run. For

a minute she was running behind him, but stopped at the elementary

school. When she heard gunshots she crumpled to the ground. She

had a feeling Chris was dead.

Judging

by the amount of meth found in his blood, he certainly must have

been feeling its effects as he pulled the knife on the probation

officers. After Chris backed the officers out of the house, it's

Omstead's contention that he dropped the knife. (Police said

they found the knife at the scene.) She said she saw him use

both hands to hike up his shorts when he started to run. For

a minute she was running behind him, but stopped at the elementary

school. When she heard gunshots she crumpled to the ground. She

had a feeling Chris was dead. "He

wanted to get out of this town," she said. "He was

trying to find himself."

"He

wanted to get out of this town," she said. "He was

trying to find himself."