|

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | MEDIA MAVEN | STAGE MATTERS | DIRT | ARTBEAT November 2, 2006

story and photos by HEIDI WALTERS

THE BEAR LIKED ACORNS, ESPECIALLY WHEN HE FOUND THEM CONVENIENTLY DROPPED ONTO THE SMOOTH DIRT PATH THAT WOUND BEHIND THE CAMP to the river. He also liked grubs -- and the wood pile in camp, with those tidy little chunks of tree all split up nice and paw-handy, made it easy for him. All he had to do was swipe a good rotty one up, hug it close and gnaw until the grubs nestling in the fibers popped out like candy into his mouth. And berries, of course -- who didn't like berries? But the thing the bear liked best of all -- loved, with a passion second only to the thrill of a fortuitous pounce on a salmon in the river -- was wasps. Well, OK -- maybe what he really, really, really loved was those times when he happened to wander, all careless-like, up to that big, ripe-smelling metal box in camp -- at night, when the humans were sleeping -- and found the lid easy to open. Then, oh, the riches to be had! Chicken bones and fat rinds off steak and half-mawed burger buns and slimy bits of salad-and-potato and carrot skins and yummy rotted things that he couldn't believe those people, those spoiled kids and camp counselors, didn't want to eat. That was bounty, that was heaven, but that happened less and less these days because, lately, the bear couldn't get the damned lid open. But wasps were delicious, wild, special. A little tricky, sure. The bear could snuffle his way slowly to the spot in the dirt where he could sense the wasps nesting underground. But then he had to dig rapidly, clawing deep and fast, and quickly scoop the seething, tickling mass of wasps, paper and dirt into his mouth. Later, of course, he could poop out their bits of shimmering, chartreuse body parts at his leisure, leaving behind big be-sequined piles.

Left: Kim Cabrera, aka "Bear Tracker." A few weeks ago, as the day slanted toward evening, Kim Cabrera walked purposefully across the high, mown meadow above the camp's main lodge, a camo-colored daypack on her back and a walking stick/tracking stick in her hand. She was intent on showing a reporter the spot where a bear had recently routed out and devoured a family of wasps. The 41-year-old Cabrera -- herself looking like a small bear, stout, curious, with smart, shining dark eyes and glossy, short brown hair -- paused and pointed at a soft, rototilled-looking patch of dirt. "This is turkey scratch," she said. There were big, birdy toe marks in the powdered dirt; nearby, a feather and some long cylindrical grassy lumps of turkey scat. "They're looking for whatever they can find under there to eat: seeds, ants. They like acorns. And this," she added, pointing to a bit of earth unscratched by turkeys that had a faint tennis-shoe-sole pattern in it, "looks like human sign. The soil's a little bit harder here because it got rained on, so there's a little crust. And you don't see regular patterns like that in nature, especially with parallel lines like that. Well, a bird wing, maybe." Next she stopped at a bear-chewed log. Then, she approached a dark hole in the ground, knelt down and lifted up two empty honeycombed paper slabs of former wasp house. She swiveled and pointed out two glittering piles of bear poop. "They love these things," she said. "He really scored when he got that wasp nest." A flying raven cawed, its shadow floating over the ground. A door on one of the empty cabins creaked, nudged by the breeze.

The funny thing is, Cabrera and lots of other trackers don't seem to really care if they ever actually see the animal. Oh, that would be a bonus. But the story it leaves behind in the dirt, leaves and rocks is sustenance enough. "I like to keep track of who's here, and what they eat," Cabrera said. "As a naturalist, I think that helps me learn more about the animals, and I think it gives me a connection to the land." Right: Wild turkeys at Camp Ravencliff. Cabrera has done upkeep and general maintenance at Camp Ravencliff for 10 years. But over the past month she'd been getting the camp ready to host the annual gathering of the International Society of Professional Trackers (ISPT), which was held in mid-October. Many of the world's top animal and man trackers would be there, including South African Louis Liebenberg -- an innovative scientist and leading authority on tracking -- and his countrymen, nine of South Africa's 18 senior trackers from some of the country's major game reserves. Cabrera, an avid tracker and an ISPT member, had been spending her afternoons at the camp preparing tracking exercises for the participants and airing out the cabins. Trackers? Tracking? Yes. To be able to track is to be able to find food, a lost person, a thief, a poacher, an illegal border crosser or perhaps a magnificent leopard for a camera-wielding, high-paying ecotourist. It is to pursue an elusive story. To reconnect to the natural world. Liebenberg, a tracking software developer and author of the book The Art of Tracking: The Origin of Science, even surmises that it was thousand of years of subsistence hunting -- i.e., tracking -- that gave modern humans our particular intellect. That, if so, would appear to be a mixed blessing: Because of modern humans, much of the natural world is disappearing. Now, rather than tracking for food, it seems we track to belatedly connect with -- and to record -- what we are losing.

The bear wandered over to the dumpster in camp, just to see. He couldn't open it. But it didn't smell, anyway. It was here at this dumpster, actually, in 2001, that a mountain lion had killed a deer. She had hung around 13 days afterward, eating and then retreating to one of her four little matted-down-grass lion beds with a view of the kill where she could curl up, rest and keep guard. Finally, she had dragged the carcass off into the woods. The bear sniffed around the lodge a bit, then ambled along the path and took the spur descending to the river, his big feet leaving large, kidney-shaped tracks in the soft earth. Before the river bar he swung left and bashed a path through the sweet-smelling blackberries, crushing minty pennyroyal and aromatic mugwort along the way.

Alex van den Heever sprawled back on his arms with his legs bent awkwardly in front of him. His rifle had flown from his fingers. His heart thun dered, he couldn't breathe right, his white face had grown even paler and his mind urged him to lunge back up and run, run. The big cat -- gorgeous, enraged, deadly -- practically stood over him where he'd flung himself after she'd leaped from hiding to confront him and his coworker, tracker Mathanjana "Renias" Mhlongo. Every time he made a quick panicky move, she advanced, menacing. Renias spoke quietly to Alex, telling him not to move fast. To drop his eyes. To slowly edge back. Alex did this, and each time he incrementally eased back the cat relaxed a bit more, sensing he wasn't a threat. Finally, she too backed away and then ran off. Van den Heever stood up off the floor inside the

main lodge at Camp Ravencliff. It was Friday evening, the first

day of the tracker symposium, where about 60 people had assembled.

The vision of the African veldt, and "the most beautiful

leopard" van den Heever has ever seen, retreated. Renias

Mhlongo, the tracker who'd saved his life back in the African

bush that day when van den Heever was a new, green employee at

the privately run animal reserve Londolozi, stood beside him

at the front of the room chuckling at the tale. He spoke, and

van den Heever translated: "He [Mhlongo] says he first learned

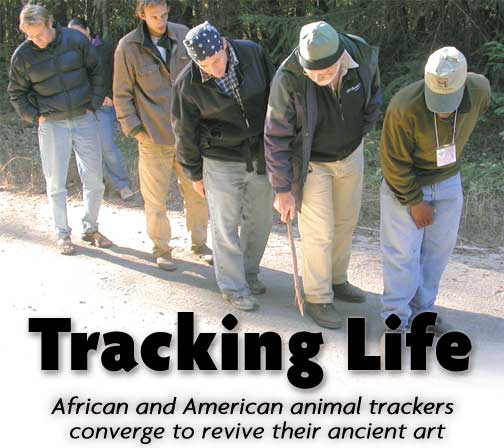

to track from his father. He grew up very close to L Left: Trackers try to "age" tracks, and conclude: They're either fresh, or they're not. But van den Heever's leopard tale was about more than just trackers, neophyte guides and pleasing the tourists. It was, as he titled it, about "The Power of Relationships." And, clearly, the two friends had told this story before -- it was so polished and inspirational, you could imagine them speaking before a suited group of Forbes 400 businesspeople in some nondescript conference hall. Or, same audience, but out on the big game reserve before a tourist photo outing. Indeed, said van den Heever later, walking down from his cabin on the grinding-stone rock, he had studied with a motivational speaker to hone his speaking skills. He'd worked particularly on this presentation. It's a fine, nuanced story: After the experienced older tracker, Renias, saved Alex by coaching him through the tense moment with the leopard, he befriended the young man, took him home to his village to meet his family and, though not rich, hired a gourmet chef to cook them dinner. Mhlongo became a mentor and best friend to van den Heever. Van den Heever said he hoped the tracker audience understood the significance, especially, of the fact that he is white and Mhlongo is black. They faced racial tension, also, and gracefully overcame it. And strong friendships could only be a good thing in the reviving world of tracking, where hunting is being replaced by ecotourism and the big reserves provide important jobs for native trackers as well as help protect the animals and their environment.

Building relationships among

the world's trackers also is a function of the ISPT, a relatively

new organization whose diverse membership includes law enforcement

officers, volunteer search and rescue people, border patrol agents,

soldiers, wildlife biologists, game-reserve employees, hobbyists

and kids-camp naturalists and teachers. And this year's tracker

symposium seemed dominated by one particularly unifying theme,

or mission, heavily pushed by th Right: Tracker and track guidebook author Mark Elbroch, at left, and ISPT executive director Del Morris of the Sonoma Search and Rescue. The man who spurred this renaissance of tracking skills is Louis Liebenberg. Over the past decade, Liebenberg has developed a pictorial icon-based software to use in a hand-held computer along with a GPS, called CyberTracker, for African Bushmen to collect data for biological studies while they are out tracking animals. The data collection, in turn, has given the Bushmen a way to make money. Liebenberg also developed a tracker evaluation system, which has been embraced by the South African government. Now, for instance, when a game reserve wants to hire a tracker, it can ask the applicant to show a certificate indicating his or her tracking skill level. Liebenberg even used his tracking system to uncover a complex network of thieves who were robbing, and sometimes murdering, tourists who trekked out onto a remote beach near Cape Town to see a shipwreck. He tracked their routes, then hid and watched them do their deeds. By knowing how they worked and where they themselves hid, he got so he was able to predict where the next attack would occur. He could even, he said, predict which tourist would be attacked. He used his CyberTracker to gather the data. And then he trained the park's rangers in tracking. But he sees endless possibilities for CyberTracker, matched with native expertise, as a biological research tool. "I'm trying to bridge the gap between professional scientists and citizen scientists," Liebenberg said. With global warming, he said, "species are disappearing under our noses." There are not enough scientists to keep track of them all, he added, but there are, in many places, people who've grown up on the land who know everything about every animal. "How many of us know how many honey badgers there are? That's where our tracker comes in. And I would like to see parallel systems for birders, for reptiles, for plants. If we've got any hope of getting any sense of what biodiversity is out there ... we've a need to just get a lot of people out there to collect data."

Left to right: South African trackers Johnson Mhlanga, Renias Mhlongo, Alex van den Heever and J.J. Minye.Left to right: His North American emissary, as it were, is Mark Elbroch, a biologist, tracker and author of several respected tracking guides. He trained in South Africa and believes strongly in the tracker evaluation system. "The difference between South African and North American tracking is, in South Africa people do it as work," Elbroch said at the conference. "In North America, the wildlife trackers are hobbyists. In South Africa, they have generation after generation of refining skills sets to find animals. In North America, the emphasis is on self-discovery, nature awareness. And on 'teaching the kids' -- teaching, teaching, teaching. But what are they teaching? The North American [wildlife] tracker never worries about finding the animals and never worries about accuracy. And the problem is, we're losing our tracking skills here. There is a need to look at our observer reliability. In North America, tracking is worn like a mantle. It's to be aspired to -- you're a 'special tracker.' And it 'defines' us. Whereas, if we just treated it as a skills set," perhaps tracking would be taken more seriously. That standardized skills set, he said, is "so achievable it's amazing." Already several North American trackers, including members of the San Diego Tracking Team, a nonprofit group that helps biologists with population surveys, have successfully completed evaluations.

The three people walked down the dirt path toward the Eel River, stopping often to shine their flash lights on the ground. It was just before midnight, Friday. The bear's tracks from a few days before had been obliterated by human traffic. Kevin Brewer, a search and rescue team member from Virginia, knelt to examine, with delight, a new and perfectly dainty set of mouse tracks. When they reached the gravel bar alongside the quietly gurgling river, they crunched along on the pebbles until Kim Cabrera, who knows this place like the back of her hand, stopped and said, "Want to see some year-old bear poop?" They shined their lights on the pile -- just a bunch of dried seeds now. Someone asked: "What's the first thing you ever tracked?" "First thing?" said Cabrera. "My goodness. First animal, you mean?" "Anything." "Coyote, I think. When I was a kid, a coyote." "Mine was probably a frog," said Brewer. "You tracked a frog? When you were a kid?" "Sure," he said. "If you've got fine river silt, you can track frogs," said Cabrera. They crunched along. Stars shot across the clear sky, repeatedly. Crickets sang, a warm, pulsing rhythm of chirp-and-silence.

Now it was 1 a.m. or so. The South Africans, and most everybody else, had gone to bed. A few trackers still gazed into the flames of a campfire. A question, tossed like a spark: Why do you track? Emil McCain, a red-haired wildlife management master's student at Humboldt State University, spoke first. "I grew up the only child on a ranch, in the middle of the wilderness in Colorado, and I had nothing to do but track animals." A pause, and then Del Morris, the ISPT executive

director and a search and rescue team member from Sonoma, said,

"You know, I was in Boy Scouts in the '60s. I grew up in

a large family. I remember playing hide and seek with my brothers

and, you know, I'd look at the ground and I'd think, they haven't

been here; if they had come this way, they would have left something.

I was thinking as a tracker even at that point. Later I got involved

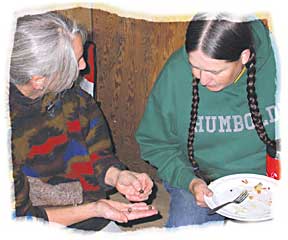

in search and rescue. When the first classes came "Dogs can't do it?" "Dogs can't do it even close," Morris said. "There is so much failure on the dog's part, that they don't even advertise it. They advertise the success stories of the dog. And it's fun to have your best friend out with you in the woods. There's a famous picture [in some book] of a cottontail rabbit trail. And the dog comes up perpendicular to it -- and he follows it the wrong way. In search and rescue, you need to know which way to go. You have to combine a human with that dog to say, 'This way!'" Everybody laughed, young Preston Taylor of San Diego the loudest -- a sort of happy, barking laugh of unabashed merriment. Throughout the weekend, one could tell where Taylor was just by his big laugh. "I would say that I like tracking because I feel alive," Taylor, who's taken the tracker evaluation test, said. "There's nothing like a zero-degree day, and a fresh snowfall, and there's perfect prints on the ground, and it's just you and the cold and the jays out, you know? It just feels great." Once, he said, he pitted himself against a dog, chasing a grey fox, and won: The dog lost the trail. Above: Trackers Tina Smith, from Pennsylvania (left), and Christine Raving, from Humboldt County, examine deer scat during breakfast.

About mid-morning Saturday, outside the lodge, four wild turkeys walked single file down the kid- glyph rock to eat the cracked corn somebody had scattered for them. The sun gleamed white on their dark backs. The trackers, all inside, didn't see them.

Inside the lodge, in the bathroom, somebody had written somewhat of an animal conundrum on the white sheet of paper tacked to the wall for partici pants' comments: "In Africa a giraffe is called 'dlulamithi, taller than the trees.' Here it is called 'panzimithi, lower than the trees.'" Out in the lodge's lit-up kitchen, Del Morris, his daughter and a couple of helpers were fixing the Saturday lunch -- Morris up to his elbows in the salad he was mixing in a giant metal bowl. In the darkened main room, the audience sat rapt while the eye-twinkling Johnson Mhlanga, a South African tracker from the private game reserve Singita Lebombo, talked about "Tracking Dangerous Game." "Elephants are the most dangerous. In my system, if I was to follow an elephant, I would keep a distance. Checking the wind -- be always downwind. You are always in good cover, which is the middle of a thicket. Talking about a lion -- not the sea lion [his audience laughed]. The lion is always a very, very dangerous animal in South Africa. The lion, for me, on foot is easy. When first you see the footprint, check how fresh it is. But also you need to be careful of size. And you need to be downwind. Lion can eat you. You can be a snack to a lion. Two minutes, and you'll be gone. Nothing left. Maybe your boots. "Now, coming to the leopard. It's a different story. You need to know how to treat them. We had the story of the leopard yesterday -- you want me to repeat it? [He fell to his butt on the ground, trembled, then laughed and stood up]. "You are following the lion -- here comes the leopard. You might bump into black rhino, you might bump into anything. Leopard: You need to be careful. Same as lion, but better camouflaged. Keep your eyes open for anything. Up in the tree: It's easy for the leopard to pick you up in the tree. You might find him following you, and then you walk around him like a dog -- ha ha. Monkeys can warn you. "Coming to the buffalo, be careful. You know the boss [he made horn signs on his head]. Buffalo doesn't give a warning. Buffalo can smash you in a minute, yes -- half a second from a distance. It's very fast, and heavy."

Elbroch interrupted him: "There's tremendous danger in making broad statements," he said. "The things you say are large and sweeping, and there's value in that. But how do we get there? Where do we go tomorrow?" Dr. K. responded, "Mark, I'm an academic!" Another scientist there said, "And that's more reason to hold your feet to the fire." Dr. K. finished his presentation. Afterward, Elbroch and Liebenberg tried to explain their exasperation. They want to see application, not glorification. "Why did the Bushmen track? To feed their families," Elbroch said. "Here, it's about self-discovery. But is that curiosity enough to keep people tracking when they need to get along in the modern world?" Liebenberg, who had spoken earlier of global warming, its effects on biodiversity and his desire to see everybody out there collecting data, added that it wasn't that he thought we could "save the world." "I think it's too late to save the world," he said. "We need to monitor it."

Late that night, in camp, there was a tremendous crashing through the brush. The bear? Then there was a scampering patter of someone running through the leaves. A lion chasing deer? Burglars? But, no. It was the resident mother deer with her two near-grown fawns, who were chasing each other around the cabins, their shapes visible in the porch light shining from one of the cabins.

Sunday morning, after breakfast and a drawing for goodies, the trackers split into groups led by the South African trackers. One group wandered south toward the river. Several groups wandered up the road -- a perfect "track trap," the dirt road was riddled with the little, sharp, split-hoof prints made by deer. But which deer? The mother and her teen fawns? Or some other black-tailed deer who'd happened to wander up the road from camp in the night, crossed the deep, gold-grass meadow, and then headed back downhill to the north of where it began?

And so the group turned, reluctantly, and followed the tracker into the empty meadow. The deer watched them, raising their front hooves hesitantly, one then the other, tentatively stepping in place. Then they, too, slowly followed. COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | MEDIA MAVEN | STAGE MATTERS | DIRT | ARTBEAT Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

"I

love bears," Cabrera said. "They're just this animal

that blunders through the woods, wherever they want. They're

at the top of the food chain, and people see them and go, 'Ah!'

But they're not very aggressive. They're vegetarians mostly.

They're curious."

"I

love bears," Cabrera said. "They're just this animal

that blunders through the woods, wherever they want. They're

at the top of the food chain, and people see them and go, 'Ah!'

But they're not very aggressive. They're vegetarians mostly.

They're curious." available

to me, it all just made sense to me. It doesn't make sense to

be on a search and rescue team if you're not going to track 'em.

There's so much evidence on the ground."

available

to me, it all just made sense to me. It doesn't make sense to

be on a search and rescue team if you're not going to track 'em.

There's so much evidence on the ground." Saturday night there was an argument. An American

professor, "Dr. K," was giving a sprawling presentation

on "What tracking can teach us about the past." Paleontologists,

he said, need to use trackers to study ancient trails; NASA needs

to employ trackers; kids need unstructured playtime in the dirt;

trackers need to conserve "heirloom runs" (remnants

of ancient trails); trackers need to track their own history

and put out a magazine; trackers can gain courage from the "justice

for males" movement; "Why is it this country memorializes

its stars with tracks? Marilyn Monroe, Roy Rogers..."; trackers

were the first artists; and, basically, trackers can save the

world.

Saturday night there was an argument. An American

professor, "Dr. K," was giving a sprawling presentation

on "What tracking can teach us about the past." Paleontologists,

he said, need to use trackers to study ancient trails; NASA needs

to employ trackers; kids need unstructured playtime in the dirt;

trackers need to conserve "heirloom runs" (remnants

of ancient trails); trackers need to track their own history

and put out a magazine; trackers can gain courage from the "justice

for males" movement; "Why is it this country memorializes

its stars with tracks? Marilyn Monroe, Roy Rogers..."; trackers

were the first artists; and, basically, trackers can save the

world.