Oct. 14, 2004

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | GARDEN | PREVIEW | THE

HUM | CALENDAR

2004 CNPA

Award 2004 CNPA

Award

Environmental Reporting - First Place

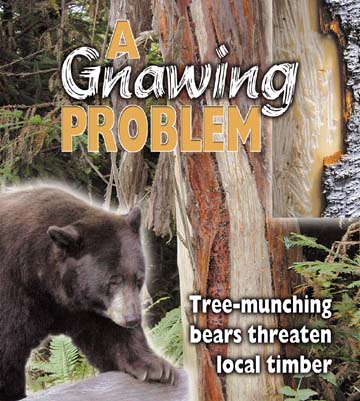

On the cover: Bark stripped

tree photo by Emily Gurnon.

Maxine, one of the resident black bears of the Sequoia Park Zoo,

poses for the cover.

Photo by Bob Doran.

by EMILY

GURNON

![[Mark Higley standing next to Hoopa Valley Tribe sign reading "Hoopa Valley Tribe - planning for the future, forestry - roads - realty, natural resources - building"]](cover1014-markhigley.jpg) Mark Higley [photo

at right] was a 30-year-old Humboldt

State graduate when he started his job as wildlife biologist

for the Hoopa Valley tribe's forestry department in 1991. His

first day there was like most first days at work: introductions

to new co-workers, papers to fill out, directions to the bathroom.

Then he met the tribe's silviculturist, or forest scientist,

who was not much for small talk that day. Mark Higley [photo

at right] was a 30-year-old Humboldt

State graduate when he started his job as wildlife biologist

for the Hoopa Valley tribe's forestry department in 1991. His

first day there was like most first days at work: introductions

to new co-workers, papers to fill out, directions to the bathroom.

Then he met the tribe's silviculturist, or forest scientist,

who was not much for small talk that day.

"Hi, my name is Paul Abbott,"

the man said, holding out his hand to Higley. "We have a

problem."

The tribe had begun seeing a

phenomenon it hadn't encountered much before, Abbott told his

new colleague. Black bears were coming out of their winter hibernation

and dining on the Hupas' bread and butter: the Douglas fir trees

whose sales generate about 90 percent of the tribe's income.

Higley now estimates that the bear damage will cut the tribe's

timber revenues by at least $1 million to $2 million a year --

about 15 percent -- within 10 years.

Just next door, to the west

of the Hoopa reservation, are 100,000 acres of redwoods and Douglas

fir trees owned by Green Diamond Resource Co., formerly Simpson

Resource Co. It, too, is finding the bears a major headache,

as are Pacific Lumber Co. and many smaller foresters.

"We've been concerned about

it for a long time, and finally got our [company's] resources

together to take a hard look at it," said Dan Opalach, timberlands

investment manager for Green Diamond.

The problem is not exactly new,

and it is not limited to California. Timber producers in Oregon

and Washington have been struggling with it for decades. Companies

here and elsewhere have tried various approaches to stopping

it -- from hunting the bears to feeding them.

![[Tree with bark stripped]](cover1014-treedamage.jpg) But it's getting worse, Higley said. And

there's a reason. But it's getting worse, Higley said. And

there's a reason.

"We've converted the habitat,"

he said. Before large-scale forestry, all the trees grew unimpeded,

so that the North Coast was covered in old growth. In recent

decades, timber companies have worked on growing trees as quickly

as possible to get the most profit. That means pruning and thinning

out the weaker trees. Those remaining get more sun and more root

space.

"The trees that they're

maximizing growth on are the ones that the bears love to eat,"

because they tend to be sweeter, Higley said. "We've made

the entire landscape into these fast-growing young stands, and

then you wonder why the bears are eating it."

Steve Horner agreed. Horner

is a silviculturist and manager of sustainable forestry for Pacific

Lumber Co. "We're creating salad bars for these bears,"

he said.

LEFT: Bear-damaged

tree. Photo courtesy Hoopa Tribal Forestry

Sweet-tooth tradition

Black bears have historically

made their home throughout North America, and are still present

in at least 40 of the 50 states, according to the Web site of

the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Service.

Scientists have noted the tree-stripping

behavior since as far back as the turn of the 20th century, Higley

said. And in Humboldt County, foresters have seen it for decades,

although the bears themselves seemed much more scarce in bygone

days.

"I've talked to a lot of

old-timers [who were loggers] about bears," said Horner.

"Back in the `30s and `40s, it was very rare for anybody

to see a bear. If they were to see a bear, it was a big deal."

Today, foresters say, it's not unusual to see two or three bears

a day.

Numbers from the state Department

of Fish and Game confirm that the black bear population is rising;

today the department estimates there are at least 25,000 to 30,000

black bears in California. About half of those live in the region

north and west of the Sierra Nevada mountains, including the

North Coast, and ours is the region with the greatest number

of bears per square mile.

Though they may have kept out

of sight, the bears of earlier days nevertheless made their presence

known. Beginning in the late 1940s, the Hammond Lumber Co. had

enough stripped trees that it began to do surveys of bear damage

on its property, said Jim Able, a private forestry consultant

who has worked on the North Coast for 35 years, starting with

Georgia-Pacific, which had by that time bought Hammond.

![[bear standing in forest]](cover1014-bearoutsideden.jpg) Researchers have found that the tree-stripping

behavior occurs in the spring, when the bears emerge hungry from

their winter torpor, and their main sources of food, such as

berries and acorns, are in short supply. It is a learned behavior,

usually taught from mother to cub, but not all bears do it. The

ones who do may sample a number of trees, stripping off a piece

of bark and scraping their teeth over the sweet cambium layer

underneath, before they find one they really like. The tastiest

trees may be completely denuded. Researchers have found that the tree-stripping

behavior occurs in the spring, when the bears emerge hungry from

their winter torpor, and their main sources of food, such as

berries and acorns, are in short supply. It is a learned behavior,

usually taught from mother to cub, but not all bears do it. The

ones who do may sample a number of trees, stripping off a piece

of bark and scraping their teeth over the sweet cambium layer

underneath, before they find one they really like. The tastiest

trees may be completely denuded.

The effect on the tree can be

catastrophic. A missing piece of bark opens the tree to infestation,

disease and rot. A tree that is stripped all the way around in

one place, or girdled, will die, because the sap cannot travel

up the trunk.

"Driving along [Highway]

299, if you look out, you can see a bunch of red trees,"

Horner said. "Those are the trees that have died after being

girdled by a bear."

The ones that have been partially

stripped may still lose a good deal of their sales value, Horner

said. "It creates a wound in the tree, and they're doing

it to the biggest and most valuable part of the tree."

With profits at stake, timber

producers throughout the Pacific Northwest have tried for years

to combat the problem. Hammond Lumber experimented with a number

of things in the 1950s to stop the bears -- including slaughtering

300 of them in one year, Able said. "A hew and cry went

up" when word of the killings reached the public, and the

company had to stop. It had achieved its goal; few trees were

damaged in the next three years or so, Able said. But the victory

was only temporary. "Within three to five years, it built

right back up again."

Timber companies may invite

hunters onto their land during the fall bear season, but there's

no guarantee that any bears killed were those doing the damage.

Companies in Oregon and Washington

reasoned that, if the bears had other food available to them,

they might stay off the trees. To try a feeding program here,

where the animals are more plentiful, might amount to "welfare

for bears," Opalach of Green Diamond said. It might only

make them dependent on the new food source and risk inflating

the population. Or the alternative food provided might not be

enough to make a difference for such a large number of bears.

In any case, it's illegal in California to feed wildlife.

Trees killed by bark-stripping bears. The tree at the right has

been girdled.

Photos courtesy of Hoopa Tribal Forestry

`That's your grandma'

When he was assigned to tackle

the bear problem in Hoopa, Mark Higley found that the tribe's

special relationship to the animals demanded some creative thinking

on his part.

The Hupa people consider the

bears their ancestors. "We can't just go out and kill them,

because that's your grandma," said Lyle Marshall, tribal

chairman. When Higley went before the tribe's Cultural Committee

to explain the problem of the trees being stripped, he was met

with a lot of questions. "They didn't want to just willy-nilly

kill bears," Higley said. "They wanted to get a real

handle on which were the problem bears -- at no small expense."

![[Jaime Sajecki points to poster showing bear teeth]](cover1014-bearteeth.jpg) So Higley and his staff, including HSU graduate

student Jaime Sajecki [photo

at right] , embarked on a painstaking

two-year study to try to identify the bears that were doing the

damage. They took hair samples from the stripped trees and sent

them to a lab for identification. Then, they captured and anesthetized

240 bears and compared hair samples from them with the hair from

the trees. The genetic tests turned up 78 "bad" bears.

Of these, 25 were killed. So Higley and his staff, including HSU graduate

student Jaime Sajecki [photo

at right] , embarked on a painstaking

two-year study to try to identify the bears that were doing the

damage. They took hair samples from the stripped trees and sent

them to a lab for identification. Then, they captured and anesthetized

240 bears and compared hair samples from them with the hair from

the trees. The genetic tests turned up 78 "bad" bears.

Of these, 25 were killed.

For her master's thesis, Sajecki

also studied dental patterns of the captured bears. The study

seemed to confirm her hypothesis: that the tree-eating bears

would have more tooth decay than the bears who weren't doing

the damage. Now, Higley's staff can continue to trap the bears

and decide, with reasonable certainty, whether a particular bear

is a trouble-maker or not -- just by peering inside its mouth.

[Photo below left: Sajecki

studies dental evidence in bear's mouth]

![[Jaime Sajecki looking into bear's mouth and measuring teeth]](cover1014-jaimesajecki.jpg) "It looks like it's going to be valuable,"

Sajecki said. "It looks like it's going to be valuable,"

Sajecki said.

The tribe has spent about $400,000

on identifying problem bears, Higley estimated. It is also altering

its basic forest practices -- which may turn out to be the most

effective measure of all. "We've changed our management

tremendously," Higley said. With no more clear cuts, and

more of the older trees left intact, new trees will grow more

slowly. The bears will be less likely to attack them.

The new pest

Dan Opalach [photo below right] remembers

talking about forest pests when he was an undergraduate in the

forestry department at HSU. Pests were things like fungus and

insects. What he doesn't remember -- even through his master's

and doctoral study -- is any discussion of tree-eating bears

threatening timber. But as he took a visitor on a tour of the

company's Crannell Tree Farm, a vast area just east of Clam Beach,

it was clear that the problem was now impossible to miss.

In some places, "if you

look closely, you can see damage on every other tree," he

said. "It's really amazing.

"In this region right here

[in Humboldt County], most of what gets damaged is redwood and

Doug fir, sometimes red cedar," he continued. "Oregon

says hemlocks will get hit."

It's only in the last two years

that Green Diamond has begun to do some serious analysis of the

tree-stripping, Opalach said. The company has started by asking,

among other things, why the bears are stripping the trees --

and why some trees and not others. "Sometimes they'll taste

a redwood and they'll walk away, and other times they'll just

strip the whole tree top to bottom," he said. "That's

the other thing we need to learn: Why are some redwoods more

tasty than others?"

![[Dan Opalach points to the forest]](cover1014-DanOpalach.jpg) The fledgling research has led Opalach to

do some things he never thought he'd do. One day, he was out

in the woods with Lowell Diller, a wildlife biologist for the

company. "We're looking at this redwood, and he pulls out

a knife and he starts hacking away at it," Opalach said.

"He said, `Taste it.' And I tasted it. And I thought, it's

not so bad." The many cloned trees in the company's nursery

may include one or more that the bears don't like, Opalach is

hoping. But that finding is likely a long way off. The fledgling research has led Opalach to

do some things he never thought he'd do. One day, he was out

in the woods with Lowell Diller, a wildlife biologist for the

company. "We're looking at this redwood, and he pulls out

a knife and he starts hacking away at it," Opalach said.

"He said, `Taste it.' And I tasted it. And I thought, it's

not so bad." The many cloned trees in the company's nursery

may include one or more that the bears don't like, Opalach is

hoping. But that finding is likely a long way off.

And the company is nowhere near

putting a dollar amount on the bear damage. "It's going

to be extremely hard to quantify," Opalach said.

Palco is also studying the issue.

"We know that there's a problem; we don't know how much

of a problem it is yet," said Horner, the silviculturist.

"The conventional way of dealing with any pests is to go

out and kill the thing. But we want to understand more about

what's going on there before we start to do anything about it."

![[Bear cub in tree]](cover1014-cub.jpg) ![[Mama bear and two cubs emerging from den in tree]](cover1014-bearfamily.jpg)

Bear photos courtesy of Hoopa Tribal Forestry

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | GARDEN | PREVIEW | THE

HUM | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|