|

Oct. 14, 2004

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | THE HUM | PREVIEW | CALENDAR

Artistic

legacies

by LINDA MITCHELL

I WAS NEVER MUCH OF A HISTORY

BUFF AS A KID. THIS aversion probably had to do with the fact

that my mother adored anything smacking of bygone eras, and forced

my siblings and me to endure one historical site and ghost town

after another. She was especially fond of California's missions

She thought nothing of taking hundred-mile detours on family

vacations to examine one. "Look at these!" she'd

enthuse over fragments of lumpy pottery housed in damp adobe

remains. "Can you believe the Indians made them by hand?"

At the time, these historical

jaunts didn't inspire much more than boredom and a firm determination

to "be here now," but eventually I came to appreciate

the cultural history of my home state. Oddly enough, my interest

in the past wasn't engaged by my original firsthand visits to

historical sites and vistas, but rather by viewing these things

through the eyes and hands of early California painters.

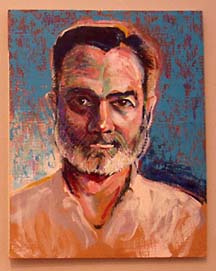

Left, "Dinner with

the McKnights" by Brenda Tuxford. Self portrait by Reese

Bullen.

Throughout my childhood and

early adulthood, I was fortunate enough to live near cities that

were early art colonies, like Pasadena, Laguna Beach and Monterey,

places with galleries and small museums brimming with the work

of artists who had found inspiration in California's historical

treasures. After seeing paintings of missions by William Keith,

Edwin Deacon and Arthur Rider, I began to study the history of

these structures with a more appreciative eye. Similarly, cityscapes

by Wayne Thiebald and landscapes by Maynard Dixon and Edgar Payne

inspired me to travel the state, rediscovering the beauty these

artists had witnessed before me.

Artists chronicle the people,

places, things and ideas in their surrounding environment, whether

they intend to or not. Studying their work can open the door

to an awareness of our connection to our cultural past, often

compelling us to learn more. On a local level, this concept seems

timely, since over the past several months some of our art community's

most influential and inspiring creative voices have crossed over

into history.

Peter Palmquist, photographer

and internationally renowned photo historian, was killed by a

hit-and-run driver in January 2003; Reese Bullen, a multi-media

artist who established the art department at HSU died last November;

we lost Justin Schmit, a sculptor who served on the board of

the Redwood Art Association, this past May; and in August came

the stunning news that Brenda Tuxford, co-founder of The Ink

People, had suffered a fatal heart attack while visiting her

son in Amsterdam.

Although these local voices

have been silenced, their place in our cultural history survives

through the work they produced. I used to think that once an

artist was gone, their work became finite, something historians

could examine in its entirety. I have discovered that artists

live on through their work and their contributions to the community,

continuing to teach and inspire future generations infinitely.

Consider the exhibition of Reese

Bullen's work at the gallery named in his honor at HSU (through

Oct. 23). When Bullen arrived in Arcata in 1946 with his master's

degree from Stanford University, Humboldt State was a small liberal

arts college. Bullen established the art department, hiring teachers,

developing a curriculum, and expanding the program throughout

his 30-year tenure. He retired in 1976, but his influence, as

an educator and visual artist, continues to be felt today.

For me, the most compelling

pieces in the Bullen exhibit are the artist's acrylic paintings

on paper from the `80s, works that hover between reality and

complete abstraction, with crisp, complex layering of colors

and heartbreakingly eloquent brushwork. Yet equally compelling

and historically significant are examples from his time spent

educating future artists at HSU. The exhibit includes early ceramics

and watercolors, as well as photos and demonstration pieces from

his calligraphy classes and two wonderful portraits of the artist

and his wife, Dorothy, from the early `50's. These paintings

capture the couple's youth and intensity at a specific time in

our regional history.

Similarly, the etchings, paintings,

and handmade books in Brenda Tuxford's current retrospective

exhibit at A.G. Edwards in Eureka (through November) illustrate

the artist's presence during a specific era on the north coast.

Tuxford moved to Humboldt from Saskatchewan, Canada in the late

`60s, during that "back to the land" movement. She

met Libby Maynard while they were both pursuing their master's

degrees in art, and the pair founded The Ink People Center for

the Arts in 1979.

Throughout her 25 years of serving

the art community at The Ink People, Tuxford touched and inspired

many lives. Stories about her talent, generosity, wisdom, and

sense of humor abound and remain evident in the art she left

behind.

The work in Tuxford's retrospective

exhibit is almost entirely figurative and narrative, expressing

in a whimsical yet elegantly rendered manner her interpretation

of the people and environment that surrounded her while she lived

here. A prolific artist, Tuxford was constantly experimenting,

reinventing and recycling her work in a variety of media as she

sought to chronicle the time she spent among us.

And perhaps the most prolific

voice of all, in terms of local cultural history, belonged to

Peter Palmquist. A professional photographer, Palmquist was also

a prodigious collector, writer and internationally respected

authority on the history of photography in the American West.

His collection ultimately came to include more than a quarter-million

photographs and much of his archive is permanently housed at

Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(See Journal cover story "A Photographer's Obsession,"

Jan. 24, 2002)

The most recent exhibition of

Palmquist's work at the Morris Graves Museum paired his photographs

with those A.W. Ericson (1848-1927), one of many local photographers

whose work Palmquist collected and wrote about. The combined

work furnished nearly a century and a half of images featuring

significant people, places and events in our county's history,

images destined to bring the past alive for generations to come.

In the literature accompanying

the Palmquist-Ericson exhibit, it was noted that Palmquist "spoke

of photographic images as collective `twigs' on our global society's

`family tree'." I'd like to extend that analogy to all visual

images. Studying these twigs can lead to an understanding of

where we've been, where we are, and what it's possible to achieve.

n

Linda Mitchell can be reached

via

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | GARDEN | THE HUM | PREVIEW | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|