|

COVER STORY | IN THE

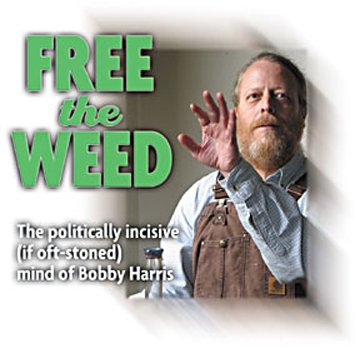

NEWS | PUBLISHER September 15, 2005

|

|

"Prop. 215 was a work of art," Harris said in the front room of his home last month. "It was a work of genius. It was really nobody's work in particular. The legal mind did a good job in this one respect: It crafted the approach of the initiative in a very astute, very effective, very powerful way." Harris is himself a medical marijuana patient. He estimates that he smokes about an ounce a week — mainly, he says, to control his alcoholism. Whether despite or because of this heroic intake, he can speak extemporaneously for hours at a time on his chosen subject, deploying his soft, lulling voice to make his case. His case, in this instance, is that Prop. 215 has never worked as the voters intended it to. |

|

"Harris ... is perhaps the closest thing to a hero in the struggle to achieve implementation of [Prop. 215]," editorialized the Orange County Register in May 1998, two years after the passage of Prop. 215, in reference to his work for the city of Arcata at a time when municipalities around the state were still trying to get their heads around how to coexist with a drug that could be legal in some circumstances but not in others.

Nine years after California voters approved Prop. 215, Harris thinks that state and local governments still haven't figured out what the initiative means. He blames elected officials, who he says have largely caved in to the state's powerful law enforcement lobby. He also blames his fellow medical marijuana activists, who in his judgment have done the same.

These days, armed with little more than a Rolodex, a computer and a flair for argument — he doesn't own a car, and is living on a very limited income — he's dedicating his peculiar talents to setting everyone straight.

The targets of his campaign, meanwhile, seem dedicated to a different task: avoiding his phone calls.

What makes Bobby run?

In 1990, Harris was a barely employed, politically active resident of the Central Valley town of Woodland. A native of Utah and a former philosophy student, he had just come off a stint working as a lobbyist and legislative analyst for the California Coastal Commission. He had taken some time off to read his favorite philosophers deeply, and was something of a gadfly in city politics.

Former

Woodland Mayor Gary Sandy said last month that Harris shook up

the politics in the town, largely for the better. Even then,

he was a conspicuous hippie in a largely Republican town, but

he was making strong arguments about Woodland's future —

in particular, that the city should preserve and restore its

historic downtown.

Former

Woodland Mayor Gary Sandy said last month that Harris shook up

the politics in the town, largely for the better. Even then,

he was a conspicuous hippie in a largely Republican town, but

he was making strong arguments about Woodland's future —

in particular, that the city should preserve and restore its

historic downtown.

"Bobby was quite a compelling public figure," Sandy said. "He was intelligent, he had a lot of energy, he was someone who was open-minded."

In early 1990, Harris decided to run for city council. He ran a campaign pledging to revitalize downtown, something that the city's old guard had deemed a waste of time and money, according to Sandy. But just a few short weeks before the election, his campaign was ended, for all intents and purposes, by the Woodland Police Department.

On Feb. 27 of that year, the police — who said they were acting on a tip — raided Harris' home and found 20 marijuana plants growing in the basement. He was arrested, and newspapers across the state jumped at the story.

A week later, Harris' plight had passed from the news pages of the San Francisco Chronicle to the desk of Herb Caen, the paper's star columnist.

"Let us start the bidding," was the breezy opening of Caen's column of March 5, 1990, "with word that Robert Emery Harris, a candidate for Woodland City Council — Woodland's over there near Sacramento — has been arrested on charges of cultivating marijuana for sale. He's a neighbor of Bob Saucerman, a Sac'to newsman, whose wife, Lee, urged, `We should go down to the jail and tell Bobby we'll help.' When Saucerman asked how, she said brightly, `Well, if he's going to be gone for a long time, we could water his plants.' Right. What are friends for?"

But things weren't so amusing on the home front. Harris lost the election, but worse, the Yolo County district attorney decided to prosecute the case to the maximum extent of the law — which, at the time, authorized him to pursue the seizure of Harris' home. Harris fought the case, acting as his own attorney.

|

Jack Durham, the editor and publisher of the McKinleyville Press, was working as a reporter for the Woodland Daily Democrat. Durham said last month that Harris was a perennial fixture downtown and in the newspaper's offices, where he would come to discuss the particulars of his case with reporters, often for hours at a time. In the end, it was for naught. The court ordered Harris' home seized and sold at auction. "At the time, I don't think I fully appreciated what a blow it was for Bobby to lose that house," Durham said. "It was a classic Victorian with lots of character. Bobby loved that house. Then they took it away. It was a crushing defeat." |

|

"The social contract — with me, it was broken," Harris reminisced last month. "I was radicalized."

But even after the court had confiscated his home for what would today be considered a trifling amount of marijuana, Harris continued to fight. He had no home and only a part-time job as a legal researcher, but he took his battle to the state legislature, aiming to ensure that what had happened to him would never happen to anyone else, ever again.

He came with a strategy — to form a coalition between Democrats and Libertarian-leaning Republicans in the state Capitol to reform state rules on the seizure of property, and to reform the court system to make it easier for people to represent themselves.

It worked, for a time. One of Harris' proposed bits of legislation was to reform the way depositions are recorded. He learned, from fighting his own case, that California state law required the use of stenographers, or court reporters, to record all proceedings leading up to a trial. The court reporters charged — and still charge — very high fees for their work, and Harris was having a difficult time paying for them.

He later learned that in federal proceedings, the parties in a case had the option of allowing for electronic taping of depositions, which drastically decreased the court costs. Despite the fact that a similar bill had been defeated in the legislature before, Harris found a sponsor — Orange County Republican Assemblyman Scott Baugh — to champion the cause.

When a key committee passed the bill, the press took notice. Bill Ainsworth of the Recorder, a San Francisco legal paper, noted that the odd couple of Harris and Baugh had succeeded where others had failed.

"Bobby Harris may be the only Capitol lobbyist to describe himself as 'meaningfully homeless,' but he has achieved something one of the state's most powerful legislators could not," Ainsworth reported. "He has defeated — temporarily at least — the court reporters' lobby." (As it turned out, Harris' victory was short-lived. Under pressure from that lobby, the bill died on the floor of the Assembly.)

Bobby's vow

Along with his lobbying activity on seizure and court reform, Harris had been poking around the early legislative efforts to legalize marijuana for medical uses. When Prop. 215 passed, he accepted an invitation by a Humboldt County patients' group to move to the county and help set up a local system of implementing the new law.

But even after all these years, Harris said, the state has still not heard the message of Prop. 215, a very simple initiative that said, in essence, that patients may have access to marijuana if their doctor authorizes it. When California voters approved the initiative, that right was incorporated in the state Constitution.

In particular, Harris faults last year's Senate Bill 420, sponsored by Sen. John Vasconcellos (D-San Jose). SB420 set statewide standards for how much processed marijuana, and how many plants, a medical marijuana patient would be allowed to possess at any time. It also instituted a voluntary statewide identification card system for medical marijuana patients.

|

From Harris' way of thinking, the Vasconcellos bill was flagrantly unconstitutional, as it modified, through an act of the legislature, a right approved by the citizens of California, though the initiative process. Voters said that patients get their marijuana; the Vasconcellos bill placed limits on that right. Harris believes that SB420 was essentially a compromise to the state's powerful police officers' lobby. Police oppose 215, he says, because it makes their jobs more difficult. How to distinguish, in the field, between a medical marijuana user and an illicit one? One answer is to institute a mandatory ID card program, which Harris opposes on civil liberties grounds. |

|

Any other answer is stickier. A person can show an arresting officer a doctor's prescription, but the officer might question if the prescription in question is authentic or forged. How can the officer confirm that it is valid?

Harris maintains that as in any other case of suspected crime, the burden should be on the arresting officer. The officer must have probable cause to assume that the patient is not, in fact, a valid medical marijuana patient. Prop. 215 wasn't invented to make his job easier.

"Law

enforcement has to respect the initiative enough to use —

you know, beyond a reasonable doubt," Harris said, laughing.

"And probable cause. With law enforcement, there's a presumption

of legality, on its face. How can you intrude into that and say,

'I don't think so. Where's your stinking card?'"

"Law

enforcement has to respect the initiative enough to use —

you know, beyond a reasonable doubt," Harris said, laughing.

"And probable cause. With law enforcement, there's a presumption

of legality, on its face. How can you intrude into that and say,

'I don't think so. Where's your stinking card?'"

This point of view — which seems to be at least a legitimate legal argument — has not been seriously entertained by the establishment, Harris charges. He cites several court cases which would appear to back him up. Nevertheless state legislators and even other medical marijuana advocates are not taking up the case.

He's trying to change that.

"I don't have many resources. I'm lobbying — I'm contacting members of the legislature. I'm contacting the machinery of the legislature that is relevant to addressing this issue. It's really coming out of a ditch trying to get anywhere."

According to some, Harris' zeal to make his case has isolated him from potential allies. Dale Gierenger, coordinator for the California chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, recently called Harris a "lone wolf, rather than a fellow activist."

"He has been a difficult person to work with," Gierenger said. "Every time I speak to him on the phone, he goes on for an hour without letting me speak to tell him I've got work to do." (Several Sacramento figures contacted for this story declined to comment on the record on Harris' activities or his arguments for fear that they would be similarly filibustered.)

|

Still, Gierenger agreed with the principles of Harris' argument: SB 420 was a flawed compromise with law enforcement, and the onus should be on the police to show probable cause for arrest, rather than on non-card-carrying medical marijuana patients to prove that they are legitimate users. This emnity with the state's Prop. 215 establishment hasn't slowed Harris — if anything, it has emboldened him. This is true to form. Jack Durham remembered Harris' dark days in Woodland, when he was defending himself at trial and his house was on the verge of being seized. |

|

"I think Bobby thought that if he took the time to explain his case, people would understand why the charges should be tossed out," he said. "He took an academic approach, carefully laying out his case in page after page of legal documents. He would come into the newsroom with thick folders filled with legal briefs and supporting materials."

Harris is employing the same, earnest approach in his efforts on behalf of Prop. 215. He's vowed to contact every candidate for the legislature and the governorship between now and next year's election in order to seek out their views on medical marijuana implementation. He said that he is in contact with Democratic gubernatorial candidate Phil Angelides' campaign consultants, and hopes to make the case directly to them soon.

"I'd like to make it a litmus test for whoever's going to be governor of this state," he said. "You're going to have to understand Prop. 215, finally, and assist in its implementation."

It's an argument he will continue to make — to politicians, to bureaucrats, to the media, to other medical marijuana proponents — until someone listens.

COVER STORY | IN THE

NEWS | PUBLISHER

THEATER ROUNDUP |

PREVIEW | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a letter!

© Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal, Inc.