|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ART

BEAT June 15, 2006

by LUKE T. JOHNSON

The announcer's voice cuts through the cacophony of revving engines and squealing tires: "There's a lotta girl power going on at the Samoa Drag Strip," he informs us. A quick glance around the pits and one might not understand what he means. As might be expected, most of the muscle cars and tricked-out trucks lined up to race are indeed driven by men. But look a little closer, and you will see a core group of females who are proving that men are not the only ones who belong behind the wheel of a racecar.

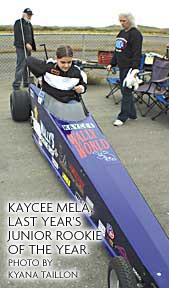

Or look at the Junior Dragster division, for 8- to 17-year-olds. The division was started in 1996 and boasted zero females for the first couple of years. In 1999, 8-year-old Kara Pettit broke the gender barrier for the Junior Dragsters at Samoa. Seven years later, Kara dominates her division, which presently features a healthy majority of young ladies. Close on her tail is Kaycee Mela, last year's Junior Rookie of the Year. If the youth movement is any indication of the direction of drag racing, women will be a force to be reckoned with in no time.

"The spectators are thrilled to cheer for the women," he says. Coming out to the track on a Sunday is very much a family event: Fathers push young ones in strollers; grandmothers hold granddaughters' hands while they wander through the pits, gazing at the cars; husbands help wives gear up for their next explosion into the horizon. Generations of Humboldt County car nuts have gathered between the Samoa Dunes for decades to celebrate their collective need for speed. No, the tracks don't just belong to the men anymore. The women have made their presence known.

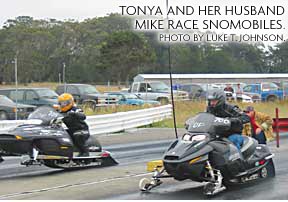

"I used to manage this place," Janis Allen informs me shortly after our introduction. Janis moves and talks with a confidence only a grandmother can have. Her long, bleached-blonde hair and soft blue eyes suggest a youthful vitality that will never go away. Janis has been drag racing for close to 10 years, though she has been on extended hiatus since her '74 Mazda truck broke down. She traces her love of cars back to her childhood. "I just love the sound of the classic cars," she says. "It sounds like when I was in high school." Her love affair with cars eventually led her to marry her high-school sweetheart. She used to clean car parts for him with gasoline and a toothbrush, hoping to entice him to give her a spin around their trailer park in his racecar. As time wore on, the rides lasted longer and longer. They will be married 36 years in October. We all take our seats in a corner booth of Denny's. Three generations of racecar drivers sit before me: Tonja Pettit, at 39 Janis' eldest daughter, is tall and attractive. She is a relatively green racer compared to the rest of her family, as she only started competing this year. She races specialty vehicles, namely snowmobiles. (Snowmobiles? you say. Indeed, these cruisers usually reserved for colder climates have found a home in the motorcycle drag racing classes across the country. They are modified with wheels and hit speeds exceeding 100 mph on the pavement). Though Tonja only recently started racing, she has been a fixture at the track for years. "It's a family thing and it's fun just to be a part of it," she says. "It's fun to be out with my husband and my kids and enjoying something with them." She was predisposed to a need for speed. She remembers riding in her parents' old '67 Shelby Mustang GT 350 when she was very young. "It was a gorgeous car," she says. "I would stand up between the seats and say `Faster, mommy! Faster!' I just loved the whole thing." Kara Pettit, Tonja's daughter, is tall and slender like her mom. At 15, she has a flippant hipness about her that only a high school girl could pull off. She has been racing since she was 8, making her a grizzled veteran compared to her mother. It would seem Kara was born with a racing bug. "I remember sitting in the stands watching my dad and just being bored," Kara says about her pre-racing years. "Then I finally got to race, so I didn't just have to sit there watching him have all the fun. I get to, now." Kara remembers when her dad would take her to empty parking lots before she was old enough to race (yes, for Junior Dragsters, "old enough" means 8 years old) and push her around in her car. He'd even let her start it up and drive it around to get a feel for the car's size. The Juniors' cars look like typical drag machines: low to the ground with long pointy noses, but for kids. But there's nothing childish about driving 80 mph while sitting mere millimeters from the ground. Kara says one of her favorite things about racing is "the look on boys' faces when I woop them and then [they] see it's a girl." Tonja agrees that a lot of the guys are shocked to see Kara out there racing. "I think people are surprised to see her get out and blow the oil out of her puke tank. Then she fixes her hair and she's ready to go." (The puke tank is used to keep excess oil from spilling onto the track).

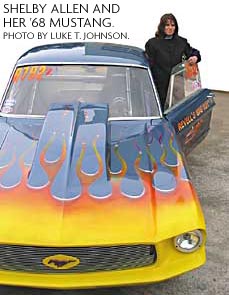

Janis' youngest daughter is soft-spoken and unassuming. Her hair is tussled. She has big brown eyes and a humble smile. She delicately picks through a basket of fries with hands calloused from years of car repair, fingers worn and stained by engine grease. A love of cars is not just in Shelby's blood — it's in her name. Her parents named her after their beloved '67 Shelby Mustang, the car, Tonja says, "that would probably be all of our dream cars." Shelby races in the Super Pro division at Samoa and, fittingly, she races a '68 Mustang. Her Mustang, not a Shelby itself, is special in its own right: It is one of only seven of that particular model made in the world, only four of which still exist. It is similar to Shelby's namesake, but with a fiberglass and aluminum frame. The car she drives was specifically designed to race. She is understandably cautious when she drives it — sometimes too cautious, her mom says. "It weighs heavy on my mind every time I go down the track," Shelby says. "I don't want to wreck it."

That all changed when Shirley Muldowny became the first female to be licensed by the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) to race supercharged gasoline dragsters in 1965. She was greeted by a chorus of boos and taunts from her male counterparts, but was never deterred. In 1973, she became the first woman to race in the popular Top Fuel dragster class, and by 1976 she was an NHRA champion. Her story was made into an Oscar-nominated film, Heart Like a Wheel, in 1983. Since Muldowny broke the gender barrier in auto racing, women have slowly filtered into driver's seats. One of the biggest sports names in 2005 was Danica Patrick, who placed fourth in the Indianapolis 500, the best-ever performance by a woman in an Indy Car race, earning her the Indy Racing League Rookie of the Year award. Still, some of the males who have dominated auto racing over the years are resistant to the paradigm shift. Richard Petty, the winningest driver in NASCAR history, has a reputation for unwelcoming attitudes toward female racers. When Janet Guthrie became one of the first female NASCAR drivers in 1976, Petty was quoted as saying, "She's no lady. If she was she'd be at home." Thirty years later, his attitude has hardly warmed; he recently told the Associated Press, "I just don't think [auto racing is] a sport for women." Petty's chauvinism is fueled in part by the seemingly meager success women have had in auto racing, particularly in NASCAR. But times are definitely changing. While the size of the female population of NASCAR drivers still leaves something to be desired, more and more women are popping up in the drag racing world, and their success is earning them respect. Melanie Troxel, for example, is the current point leader in the Top Fuel division and has proven to be a formidable opponent to the men who cross her path. Fortuna-native Hilary Will has made recent headlines on the national Top Fuel circuit. Registering the fastest speed of any racer at The Strip in Las Vegas during January test runs, she has been impressive in her rookie year on the circuit. Her strong performances won her a position as the driver for a team owned and managed by racing legends Ken Black and Connie Kalitta. Though she has struggled recently and has yet to win a Top Fuel race this year (a tough feat for any rookie, male or female), she is still ranked 12th in the Top Fuel point standings. Tonja believes that it is only a matter of time before women start to have a more noticeable presence in all types of auto racing, not just drag. "Drag racing has had women infiltrating the ranks for years," she says. "Women have been accepted in drag racing longer than in other types of racing, so it'll just take a little longer for more women to filter in." But not all men are eager to concede their monopoly on auto racing. The Samoa Drag Strip has a reputation for being family-friendly (it was highlighted on NHRA 2 Day, the weekly drag racing show in ESPN2, a few weeks ago for being especially family-oriented), and people at Samoa have been more welcoming to women drivers than some other places. But old habits die hard, even in Samoa. While a lot of Shelby's male counterparts are good sports, she says, "about half the guys" are pretty sour after they lose to her and refuse to shake her hand after a race. Even at her family's drivelines shop, she says, men greet her with cold receptions on the phone when she calls to order parts. They often ask if there is a man around they can talk to. "Anytime a woman wants to go anywhere in a man's world they've got to work twice as hard as the men do," Shelby says. Janis agrees that it took a while for the men at the track to warm up to the idea of a woman racing against them. She used to get dirty looks from men as they lined up against her. "I'm a grandmother and I was 50 years old, so the first couple years they just assumed I didn't know what I was doing. People really wouldn't talk to me much," she says. But then she started winning. After a couple first place finishes, the dirty looks turned into envious gazes. On days Janis was not able to make it out to the track, men eager to dethrone the "Hot Rod Grandma" asked her husband, Jackie, where she was. Now, working as an assistant starter, she has the respect of the men around her. She says they often come up to her afterwards and tell her they really appreciate her work. Shelby has performed well in her races, collecting a number of second- and third-place trophies. But she has never quite gotten over that first-place hump. She has instead earned the respect of her male opponents with a lot of hard work and a wealth of mechanical knowledge. Her mom brags about how Shelby is able to disassemble her entire car and put it back together. She need only listen to an engine and she'll know what's wrong with it, Janis says, beaming with pride. Kara says she also got a lot of funny looks when she started racing because she was the only girl in her division. But like her grandmother, she quickly earned the respect of her male opponents once she started beating them. Since the boys in Kara's division have grown up competing against girls, they tend to be more accepting of the females at the track. Kara's younger brother, Mike Jr., who also races, has to endure the agony of not just losing to a girl, but losing to his sister. Still, he makes a point of congratulating all the winners, regardless of their gender.

"You're not getting dizzy going around in circles," Shelby says pointedly. Drag racing, after all, takes place on a quarter-mile straightaway, not the oval loops of NASCAR or IndyCar (or, as Kara calls them, "Roundie-boundies"). Part of the reason Kara is attracted to drag racing is because the cars are the real stars and the drivers themselves are less scrutinized. "You get to actually show off your paint job more than anything," she says. "You can show off your car instead of yourself." Tonja adds, "The best thing about it is you can have a nice car, it can look good, and you don't have to worry about someone side swiping you every two seconds." But they all agree that nothing compares to the sensation of traveling at speeds that would land any of us everyday highway drivers a hefty traffic ticket.

If given the chance to race any vehicle, Kara knows right away what she would pick. "Top Fuel dragster, all the way," she says. "I would enjoy the rumble sitting in the seat, and the acceleration as you pass and just feel your head slam back." Indeed, Top Fuel cars are some of the fastest accelerating vehicles on the planet, going from 0 to 100 mph in less than a second, and approaching top speeds of 330 mph. But none of these women have ever traveled quite that fast in their cars. Kara, who is "always big for speed," her mother says, has to settle for the 85 mph limit put on the Junior Dragsters. Tonja's snowmobile maxes out at around 100 mph. Shelby, who races in the fastest division at the Samoa Drag Strip, says her top speed was 130 mph. Unfortunately, she redlighted that particular race (meaning she left too early and got disqualified). "It was still a lot of fun," she says about her moment of maximum velocity.

"I was high for about four days afterwards," she says. "I always want someone to have that feeling that I had when I won that first first-place trophy." These days, Janis is awaiting her chance to get back on the track. Kara continues to clean up in her division. Meanwhile, though everyone in the family would like a taste of victory, they are hardly preoccupied with it. "My big goal is to just win one race," Tonja says. "It's about trying to better myself each time. It's a learning experience, and it's fun for me." Win or lose, the generations of Allens and Pettits have grown closer with their high-speed pursuits. Week after week, Janis, Tonja, Shelby, Kara and the rest of the ladies at the Samoa Drag Strip prove that women do have a place in auto racing. As more and more women flock to the track, men will see that a woman's place is not just on a risque calendar, not just in the passenger's seat, but behind the wheel as well. And in the winner's circle. COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ART

BEAT Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

.jpg)

.jpg) A

lot has changed on the strip of land that sits just north of

the U.S. Coast Guard Base at the end of Samoa Blvd. What was

once a blimp landing pad during World War II was converted into

a race track in 1955. Back then, only men raced. Danny Wright,

current president of the strip, has been a part of it since 1973.

He says only recently has there been such a swell of women at

the track. As more women race, he says, more women come to watch.

A

lot has changed on the strip of land that sits just north of

the U.S. Coast Guard Base at the end of Samoa Blvd. What was

once a blimp landing pad during World War II was converted into

a race track in 1955. Back then, only men raced. Danny Wright,

current president of the strip, has been a part of it since 1973.

He says only recently has there been such a swell of women at

the track. As more women race, he says, more women come to watch. I scan

these generations of Denny's patrons, searching for one particular

family of racecar drivers who exemplify the evolving spirit of

the Samoa Drag Strip. Another jingle behind me and a young waitress

walks quickly toward the door, wide smile, arms spread. I turn

to see her locked in an eager embrace with the eldest of a group

of women who has just walked into the restaurant. With hugs and

smiles all around, this is clearly a happy reunion. The Allen

family has arrived.

I scan

these generations of Denny's patrons, searching for one particular

family of racecar drivers who exemplify the evolving spirit of

the Samoa Drag Strip. Another jingle behind me and a young waitress

walks quickly toward the door, wide smile, arms spread. I turn

to see her locked in an eager embrace with the eldest of a group

of women who has just walked into the restaurant. With hugs and

smiles all around, this is clearly a happy reunion. The Allen

family has arrived. The

Denny's door jingles open again. "Auntie!" Kara exclaims.

Just off from a long day of work at her family's business, J

& J Drivelines in Fortuna, Shelby Allen, 31, joins us at

our corner booth.

The

Denny's door jingles open again. "Auntie!" Kara exclaims.

Just off from a long day of work at her family's business, J

& J Drivelines in Fortuna, Shelby Allen, 31, joins us at

our corner booth. "It's

the adrenaline," Shelby says. "Going from a standstill

to a hundred miles an hour ... it's a rush."

"It's

the adrenaline," Shelby says. "Going from a standstill

to a hundred miles an hour ... it's a rush." By

the end of the afternoon, a small handful of drivers will be

crowned winners of today's event. Most will go home and prepare

for the next big race in two weeks. For the Allens and the Pettits.

First-place trophies have been elusive for some, and occasions

of euphoria for others. Janis vividly remembers the first event

she won.

By

the end of the afternoon, a small handful of drivers will be

crowned winners of today's event. Most will go home and prepare

for the next big race in two weeks. For the Allens and the Pettits.

First-place trophies have been elusive for some, and occasions

of euphoria for others. Janis vividly remembers the first event

she won.