|

by KEITH

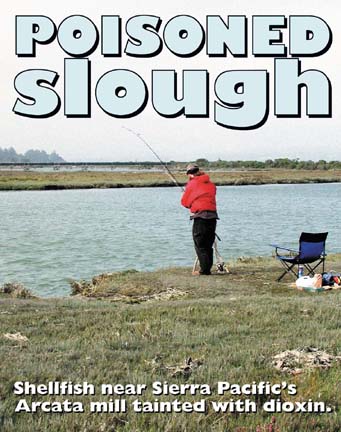

EASTHOUSE ON A BLUSTERY DAY LATE LAST MONTH, JEREMY DANNER STOOD FISHING on the banks of the Mad River Slough. A friend, Lisa Blayney, hunkered down in a lawn chair, bundled up against a chill wind. She was keeping an eye on her fishing pole, which she had stuck into the ground in front of her. To an observer for whom the passion for fishing is a mystery, it didn't look like much fun; nor was the setting very inspiring -- just off Samoa Road, with the sprawling Sierra Pacific Industries lumber mill looming directly across the waterway.

Blayney was so deeply ensconced in her chair that it was hard to tell whether she was enjoying herself, but Danner seemed to be having a good time. A lanky, bearded young man, Danner is a College of Redwoods student with an interest in becoming a fisheries biologist; he hopes to work for the California Department of Fish and Game one day. When asked if he eats the fish he catches in the slough, he said usually not. "I just catch them for the sport" and throw them back, he said. He seemed unphased when told that dioxin from the mill across the way was present in sediment in the slough. He's from the delta region near Stockton, which he said is polluted. "It's pretty much normal for me not to eat what I catch," Danner said.

The water board actsRussell and Ehresman aren't the only ones with concerns about the slough. On June 4, the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board sent a letter to Sierra Pacific requesting that the company perform a "human health and ecological risk assessment" of the slough. The letter, which has not been made public until now, notes that in June of last year water board staff took sediment samples from two locations in the slough near the plant and found dioxin. The letter says dioxin, one of the most toxic chemicals known, was also found in sediment in a ditch on the mill site. "The available information indicates that discharges from the facility have impacted the slough sediments near the facility and (that) additional work is necessary to determine the extent of the contamination and the associated risks to human health and the aquatic life in the Mad River Slough." The letter also makes reference to a recent toxicological study that found elevated levels of dioxin in mussels and crabs immediately adjacent to the Sierra Pacific mill. The study, which has also not been made public before, was commissioned by the Ecological Rights Foundation, a Garberville-based environmental group that is suing Sierra Pacific for alleged violations of the Clean Water Act. In addition to looking at shellfish near the mill, the study also collected and tested shellfish in Hookton Slough, located at the relatively pristine southern tip of Humboldt Bay. Mussels there had no detectable dioxin contamination and the levels for a species of crab were extremely low, according to the study.

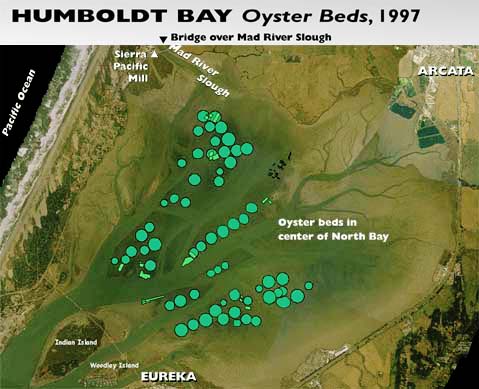

The study, done by toxicologist Marc Lappe of the Center for Ethics and Toxics in Gualala, Calif., adds that "any increase in body burdens of (dioxin and related) chemicals increases the human risk of several toxic end points including cancer, developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity, and possibly immunotoxicity." Tuck Vath, a senior engineering geologist with the regional board, said in a telephone interview from his Santa Rosa office Monday that there is cause to believe that aquatic life in the slough is ingesting the dioxin -- and is thereby creating a pathway for dioxin to enter into humans. "Dioxin is making its way into the food chain in the slough and could be impacting the resources of Humboldt Bay," Vath said. The Lappe report, along with the water board's action, has raised questions about whether dioxin from the Sierra Pacific mill is posing a threat to Humboldt Bay's oyster industry, the biggest in the state. The health and environmental concerns are becoming public just days before Arcata's annual oyster festival, taking place this Saturday. Dean Prat, also with the regional board, said it was "fairly routine" for the board to require polluters to conduct studies assessing the threat to human health and the environment. But he said this particular study will require "quite a bit of work" because of the difficulty and expense of analyzing for dioxin and because the company will be required to determine the extent to which contamination has spread. "It's a pretty big water body," Prat said. Vath, Prat's superior, said the water board does not have the necessary expertise on staff to ensure that Sierra Pacific designs and conducts the study in a proper manner. As a result, he said the board will seek input from toxicologists with the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, as well as from natural resource experts with the California Department of Fish and Game. David Dun, a Sierra Pacific lawyer, said Tuesday the company feels the water board's request is "reasonable and appropriate" and that the company will do the study. He said he did not know how long it would take nor how much it would cost. He said the purpose of the study is to determine "whether there has been any damage (to the bay) at all, and whether or not SPI would have (contributed to) that. "We believe and are hopeful that we will get a negative to both of those questions," Dun said. Dun said that whatever levels of dioxins and furans (an associated substance) are currently in the bay could have come from "a multitude of sources," especially old mill sites. He said the position of the company, which has operated the mill for some 40 years, is that it has not released any dioxin into the bay environment. "We do not agree that any dioxins (in the slough or the bay) came from our mill site," Dun said. That statement seems to be at odds with the company's own testing. Stormwater sampling conducted by Sierra Pacific from 1995 to the present detected pentachlorophenol on 43 separate occasions -- although the concentrations in recent years have declined, perhaps because of pollution prevention measures that the company has recently enacted. Pentachlorophenol is the fungicide that the company used from the 1960s through the late 1980s to treat wood. It is also the source of the dioxin at the plant. PCP, as it is known, is often contaminated with dioxins, an impurity produced when PCP is manufactured. As for the water board's sediment sampling of a year ago, Dun said that the company's scientists "don't put great weight" on that. One reason is simply that only three samples were taken. "According to our engineers, that's not enough testing to draw any conclusions," Dun said. The other reason, according to Dun, is that the dioxin levels that were detected in the sediments were low; two of the samples, he said, were low enough to fall within what is considered by regulations to be acceptable for residential areas. Many scientists believe that dioxin is so toxic that there is no safe level of the chemical. Scientists with Fish and Game and the Humboldt County Health Department, meantime, expressed support for the water board's action. Vicki Frey, a Fish and Game environmental scientist, said Sierra Pacific needs to do a health and environmental study "as soon as possible." Frey said her agency wants the company to take sediment samples, water samples and tissue samples of shellfish and fish over a broad area of the slough -- including in the Mad River Slough Channel, which extends into Arcata Bay. "We need to know what the natural resource damage is," said Frey. Jim Clark of the Humboldt County Health Department said the study should include tissue samples of fish caught from a popular fishing spot: the bridge that crosses the slough next to the plant. Clark said it will be particularly important to do sampling of fish that prey on shellfish -- such as sharks -- because dioxin concentrations become greater the further up the food chain the chemical goes. Sharks are routinely caught and eaten by people fishing near the Sierra Pacific plant. Clark said he did not think there was any need at this point to ban fishing in the area or to post warning signs. He said waiting a few more months for the results of Sierra Pacific's study wouldn't make much of a difference since the health threat is over the long term; in other words, to people who consume fish from the slough regularly over an extended period. Oyster beds safe?Jim Lamport, executive director of the Ecological Rights Foundation -- the environmental group that is suing Sierra Pacific -- said that commercial oysters in Humboldt Bay could be vulnerable to dioxin from the mill. Noting that many commercial oyster beds are located along the Mad River Slough Channel that extends out into the bay, Lamport said: "That is the tidal channel that feeds and empties the slough. These beds may be affected by contaminated sediments that are discharged from the mill, or that have accumulated near the mouth of the mill. "There are also some oyster beds located in the slough, just north of the mill," Lamport added. The toxicological report the group had done found elevated levels of dioxin in sediments 2.5 miles up the slough -- a possible indication that contamination from the mill has spread extensively throughout the slough ecosystem. Lamport said that no commercial oysters were sampled in the toxicological report "because the beds are privately owned." Lappe, the toxicologist who did the study, said that oysters are very efficient filter feeders and that they are likely to take up more dioxin than mussels. He said the fact that commercial oysters are suspended in water would not necessarily protect them from dioxin in sediments. The reason, in part, is that oysters eat creatures -- such as small, shelled copeopods -- that both lurk in the mud and swim around in the bay; in other words, the oyster's food sources may be contaminated with dioxin. If so, then oysters themselves -- just like the predators who prey on them -- "bioconcentrate" the dangerous chemical. "Oysters may be two steps removed from the creatures in the muck," Lappe said. Lappe said he was not saying that a hazard exists to the oyster beds, but that they should be tested. "It would be irresponsible to say a hazard exists. But it would also be irresponsible to ignore it," Lappe said. Frey of Fish and Game agreed, saying that the Sierra Pacific study should analyze tissue samples taken from oysters in the beds to determine if there's a problem. But she expressed a good deal more skepticism about the extent to which the beds may be vulnerable. She said the nearest commercial bed along the Mad River Slough Channel is located more than a mile south of the Sierra Pacific mill. "I don't have a huge concern over the oysters because they're far enough away and there's so much dilution from the amount of water in the bay that I doubt it would be that significant an amount (of dioxin)." "However," she added, "it still needs to be looked at." The nearest commercial oyster operation is actually in the slough itself, less than a half-mile north of the mill. But it turns out those oyster rafts, which belong to North Bay Shellfish, are a temporary storage area -- not a place, like out in the bay, where oysters are grown for as long as three years before they become marketable. Scott Sterner, owner of North Bay Shellfish, said that oysters are typically suspended from the rafts for a period ranging from a day or two to two or three weeks. The rafts are "certified wet storage," Sterner said. "I'm allowed to hold product that I harvest out of the bay before I pull them out of the water to take to market." Sterner said that in the past he has grown mussels in the slough, but that that part of his operation has shrunk dramatically due to a shortage in California of mussel seed. Another operator, Ted Kuiper, grows oyster seed further up the slough than Sterner's rafts -- in the general area where the Ecological Rights group found elevated dioxin levels in sediments. Kuiper was not reached for comment, but Sterner said it is his understanding that Kuiper's oyster seed also stays within the waters of the slough for a relatively short period before being sold to growers. There are, of course, numerous contaminated sites ringing Humboldt Bay in addition to the Sierra Pacific mill. The water board has identified 15 locations, including the Sierra Pacific mill, as cleanup priorities. There is some monitoring of shellfish in Humboldt Bay for chemical contamination under a state program called "Mussel Watch." But that effort is nowhere near as large as the monitoring that seeks to ensure that the bay's shellfish are free of bacterial contamination or of the potentially lethal naturally occurring organism known as "red tide." Another problem with Mussel Watch is that it is not comprehensive. According to Del Rasmussen, a state water board scientist involved in the Mussel Watch program, the pollutants that are typically analyzed for include metals, pesticides and petroleum byproducts. Dixon is not looked for because dioxin testing is very expensive. Additionally, there is only one lab within the state government that is set up to analyze dioxin, Rasmussen said. Sterner, along with Greg Dale of Coast Seafoods, the biggest oyster operation in the bay, said that in terms of man-made chemicals, the greatest danger to the beds would be from pollutants that would likely get released during a cleanup. "Most of the chemicals are tied up in sediments and the worst thing we can do is to go into those sites and free up the contaminants," Sterner said. "It's probably best to let sleeping dogs lie." Frozen chowderAs for Russell, his concern is that pollution -- in particular dioxin from Mad River Slough -- may be inside his own body. Rachael Brilbeck, a Manila resident, has a similar concern, although not so much for herself as for her three teenagers, "who've all eaten a certain amount of seafood" from the slough. Brilbeck has plans to post notices at the railroad bridge and down at the Manila Market about dioxin being found in shellfish in that area. Russell, meantime, has some frozen mussel chowder in his freezer that came from mussels in the slough. "I'm afraid to eat it," he said.

Aerial photo courtesy of Humboldt Bay Harbor Recreation and Conservation District IN THE NEWS | IN THE GARDEN | SUMMER FESTIVALS GUIDE | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com © Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Two views of Sierra Pacific Industries

Arcata Mill and Mad River Slough and bridge. [photos courtesy

of Steve Bond]

Two views of Sierra Pacific Industries

Arcata Mill and Mad River Slough and bridge. [photos courtesy

of Steve Bond] Howard Russell

[in photo at right with Manila resident Rachael Brilbeck] and Dan Ehresman may wish they had exercised similar

caution. Kayaking enthusiasts, they used to come to the slough

frequently for recreation -- as well as for food. Ehresman, a

former Manila resident, said he often fished from an old railroad

trestle that parallels Samoa Road near the mill site, as well

as from the banks of the slough. "I've eaten shark and mussels

from the slough," he said. Russell sometimes would fill

up a five-gallon bucket with shellfish from the area. "Some

(specimens) were as big as a tennis shoe," he recalled.

The two lost their enthusiasm for the place when they started

exploring on their kayaks and saw pollutants being discharged

directly into the slough from the mill. "We found black,

foamy, gross-looking" liquid running off the site, Russell

said, adding that the discharge smelled foul. "That's when

I started to think `maybe I shouldn't be eating fish from here.'"

Howard Russell

[in photo at right with Manila resident Rachael Brilbeck] and Dan Ehresman may wish they had exercised similar

caution. Kayaking enthusiasts, they used to come to the slough

frequently for recreation -- as well as for food. Ehresman, a

former Manila resident, said he often fished from an old railroad

trestle that parallels Samoa Road near the mill site, as well

as from the banks of the slough. "I've eaten shark and mussels

from the slough," he said. Russell sometimes would fill

up a five-gallon bucket with shellfish from the area. "Some

(specimens) were as big as a tennis shoe," he recalled.

The two lost their enthusiasm for the place when they started

exploring on their kayaks and saw pollutants being discharged

directly into the slough from the mill. "We found black,

foamy, gross-looking" liquid running off the site, Russell

said, adding that the discharge smelled foul. "That's when

I started to think `maybe I shouldn't be eating fish from here.'" Sharks caught off the Mad River Slough Bridge

Sharks caught off the Mad River Slough Bridge