|

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR April 6, 2006

It was difficult to ignore Kaylynne Reeves. Wearing a vivid orange blouse, and clearly on the threshold of tears, she did something unusual during a public comment period at a board of supervisors meeting -- she occasionally turned and confronted the audience seated behind her, eye-to-eye. Mainly, she was addressing herself to Joe Mark, the interim Chief Executive Officer of Eureka's St. Joseph Hospital. Mark, who took over the position last month, had recently announced that the hospital would be laying off a large number of employees as a means of addressing a financial emergency that was on the verge of bringing the Eureka institution to its knees. He was at the meeting that morning to inform county government of the extent of the hospital's problems. Reeves, whose 16-year-old son suffers from cancer and has been treated in St. Joe's pediatrics center, wanted to let Mark know that she didn't think much of his plan. A lifelong Humboldt County resident, Reeves was the only speaker that day not employed by the hospital. What she said turned the discussion from charts and graphs to a mother's grief. It was raw and delivered with the emotional force of a slap in the face. With her hands clasped tightly behind her back, she turned from the podium and looked at the interim CEO. "[My son] cannot be on a floor with adults," she said, her voice trembling. "He cannot be exposed to those types of things. It is important that we have a floor for our children." The Eureka hospital, one of the largest employers in Humboldt County, is in the red, hemorrhaging half a million dollars a month and living off a $10 million line of credit from its parent, the Orange County-based St. Joseph Health System. In six to eight months the money will run out. To survive, Mark had told the board of supervisors, St. Joe's must cut the equivalent of 90 to 110 full-time positions. It might also have to cut some of the services offered by the hospital, Mark continued. Reeves and others feared that the pediatrics ward -- a somewhat unique facility in an area as sparsely populated as Humboldt County -- would be one of the first to be axed. When news of the hospital's financial crisis and impending layoffs was announced last month, hospital managers told nurses that the pediatric unit -- which sometimes has no patients and is, therefore, a money loser -- might merge with the third floor medical/surgical unit, where demanding adult cases are treated. Those patients sometimes include members of the indigent population, some of whom suffer from dementia or addiction. Others are elderly and need diapers changed. In such an atmosphere, pediatric nurses speculate that children who are afraid to ask for help will be overlooked. Reeves didn't want to see that happen. Before St. Joe's began offering chemotherapy treatments a few years back, she would drive her son to Bay Area specialists regularly, sometimes having to arrange police escorts to get around road closures. "He's doing wonderful now, thanks to them," she said gesturing to the 20-or-so St. Joe nurses seated to her left, many of them wearing work clothes. She turned once more to Mark. "The burden shouldn't be put on us," she said. "It should be put on the administration, as far as I'm concerned." The nurses clapped as she headed for the door, crying. Mark said the goal was to eventually achieve a healthy operating margin of 4 percent. Costs savings are in effect already, as the hospital garnered resignations from a number of its highest paid execs, including CEO Mike Purvis, in February. The goals are "doable" Mark said, but will not be implemented without pain. In no uncertain terms, he stated the layoffs will not affect patient care at the Catholic nonprofit hospital. He maintained that the numbers reveal that St. Joe's has more employees than can be justified. One of those employees was the last person to speak -- Kathryn Donahue, a registered nurse who has worked in the intensive care unit of St. Joe's for 20 years. The example she offered had far less emotional punch than Reeves', but still it hit close to home for anyone concerned about their own health care. On Monday, Donahue was on-call and was told to come in at noon. When she arrived at the ICU "it was total chaos." Nurses had worked all day with no breaks and still needed to do their charts. She asked why she wasn't called in sooner and was informed that the ICU was trying to save money. "It's like a big squeeze on the people that are taking care of the patients," Donahue said. "All of you might be there some day and you may have a nurse who's not had a break for 12 hours." - A few weeks earlier, on March 14, the local chapter of the California Nurses Association met to discuss the impending layoffs. Sixty-five RNs came and went, filling the small conference room at the Red Lion Inn to capacity for hours. According to Donahue, it was the group's largest turnout ever. Any nurse will tell you that morale among staff has been declining for years, as the hospital began "corporatizing" health care in the county -- buying up physicians' practices then having to drop them; ignoring radiologists' needs to the point that they broke with the hospital in 2004; competing for patients and nurses with Mad River Hospital in Arcata; and, in 2001, purchasing General Hospital in secret negotiations for $30 million when, according to many hospital-watchers, it was worth around $6 million. As the hospital's financial state has worsened, mainly during the tenure of CEO Mike Purvis, so have employee relationships with administrators.

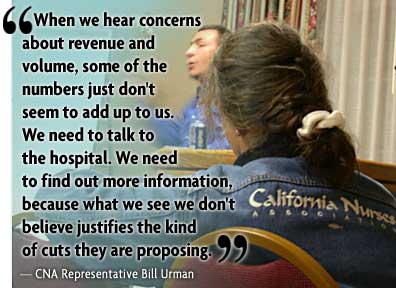

In other words, either you get dumped or you get dumped on. Nurses have already taken on more duties than they would like. When housekeepers' hours were scaled back by administration in recent months, nurses started changing linens, for instance. "What are they going to make us do next?" one nurse asked. "Mop the floors?" Little things, like overflowing garbage cans and unanswered phones, already occur regularly at St. Joe's, the nurses said, and they think it might just be the beginning. Union member Susan Johnson said that nurses fill out "assignment despite objection" (ADO) forms on a daily basis. (The forms are for the nurses' protection from lawsuits; they fill them out when they are required to work in an environment they believe is unsafe.) Lately, more nurses do not file the forms because they're just too tired by the end of their shift, Johnson said. But she warned that if a patient neglect case is ever filed -- "The hospital won't stand behind you and say, `Oh, she had too many patients." Johnson said that at least one overworked nurse who didn't fill out an ADO has had their license stripped, but she wouldn't name names. It was also the nurses' contention that non-unionized "at-will" employees, like housekeepers, many of whom do not speak English, won't complain about conditions because to do so would be to risk being fired. Another nurse wondered out loud if it was appropriate for Interim CEO Joe Mark to tell hospital staff at an employee forum not to air the hospital's "dirty laundry" to the media. "What about our freedom of speech?" another RN barked above the grumbling. One nurse conjectured that the administration was successfully scaring employees and the union and apparently controlling the media with sporadic and well-organized conferences, because the Times-Standard was "still writing about Bill the Chimp." Increasingly, more questions than answers were floated, and a palpable wave of bitterness and anxiety swept over the room. RN George Batiste saw things differently. "No, now we're getting more organized," he declared. "Now we hit the sidewalk. They do not like that negative publicity. We've got to stir the pot. "I know I'm not going to be taken off to slaughter like a little lamb." By virtue of his brazenness, it seemed that Batiste, an African-American man with glasses and a clear, deep voice, began to steer the group toward a proactive posture rather than a defensive one. "I'm not afraid of these turkeys," Batiste said, referring to St. Joe administrators. "I'll put my head on the chopping block right now." He suggested organizing an informational picket, talking to the media, writing letters to the editor, and holding a candlelight vigil. The truth, he said, would hurt the administration. His positivity was rubbing off. The nurses gradually seemed more like lions than lambs. They told themselves that they are the true advocates for patients, the "heart of the hospital" and "more powerful than we think." Union rep Bill Urman, from Oakland, said that the CNA would be requesting financial information from the hospital, so they could find out if money was mismanaged. (Urman is expecting to receive the information this week.) "We've got to take our hospital back, folks," Batiste said. "That's all there is to it." Two weeks later, an e-mail from union leader Lavon Divine-Leal urged CNA members to attend the next union meeting, which was scheduled for the night before Mark was to address the board of supervisors. "Let's put a `face' to the proposed layoffs, not just a theoretical discussion!" The e-mail went on to say: "Our CNA stance is opposition to ANY LAYOFFS IN ANY DEPARTMENT. WE ARE ADVOCATING FOR ALL EMPLOYEES. To believe that patient care won't be affected by layoffs is folly and pretense, smoke and mirrors. There are too many unanswered questions about this situation that need to be reflected in the light of day." - Supervisor Roger Rodoni wanted to know -- how did Humboldt County's health care spiral down so? Where there were once three hospitals in Eureka, now there remained only one struggling outfit. Joe Mark couldn't speak to the history of local issues, but said that currently, the hospital carries too much staff, has a large number of non-paying, indigent patients and has a high MediCal percentage that reaps only 19 cents on the dollar. On average, he said, the entire medical center collects 31 cents on the dollar. The remaining 69 cents is written off "as a contractual discount, or it's the cost shift that's taking place for those who are not paying anything, to not paying enough, to the very small percentage that are still paying some percentage of charges. That's a national phenomenon that's not unique to Humboldt County." What is somewhat unique to a county of this size is the money the hospitals shell out for the poor. Unfunded care and voluntary services amounted to $32 million in 2005 between Joe's and Fortuna's Redwood Memorial. Queen of the Valley Hospital, in Napa, which is comparable in size and also part of the Catholic health system, contributed $20 million. To close the gap and maintain services at the hospital, Mark said, philanthropy from the community and, possibly, a new county tax district, will be required, in particular to fund money-draining emergency services. But Mark said that even if those funds materialize, it still will not be enough to cure St. Joe's. "Then we need to go downstate together and be able to talk to our elected representatives in Sacramento and talk about what can the state do to recognize what's truly unique about the situation in Humboldt County," he told Rodoni. "And if necessary if that's not enough we're gonna have to approach the feds in the same thing." He says that better times are ahead. But CNA Representative Bill Urman countered Mark's presentation by arguing that the hospital administration seemed loath to discuss the problems that had brought St. Joe's to the brink, and even called into question whether its crisis was as serious as it seemed. Though the hospital has not been forthcoming with the CNA's requests to view financial information, he said, he did share with the board public documents submitted to the California Office of Statewide Planning and Development . The documents reported that from 2001 through 2004, gross patient revenue and net patient revenue increased by 50 percent and 20 percent, respectively. The most recent numbers for 2005 indicated the trend was continuing. How could St. Joe's be suffering, he wondered, considering that business seemed strong? "When we hear concerns about revenue and volume, some of the numbers just don't seem to add up to us," Urman said. "We need to talk to the hospital. We need to find out more information, because what we see we don't believe justifies the kind of cuts they are proposing." -

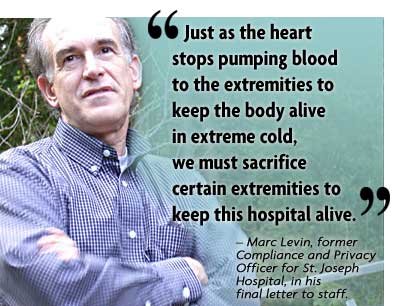

Six-year CEO Mike Purvis resigned on Feb. 28, shortly after several top-tier administrators -- Chief Financial Officer Galen Gorman; Chief Operating Officer Mary Ann McCrea; Vice President of Business and Strategic Planning Ann Orders; Co-manager of Laboratory Services Ellen Jackson; Director of Values Integration Mike Goldsby and Compliance and Privacy Officer Marc Levin -- also tendered their resignations. (The word "resignation" was used in each of these cases, but no one's sure whether the administrators in question weren't told to leave.) Hospital spokespeople would not say what the severance packages for the administrators totaled, or if it was siphoned from the $10 million line of credit extended to the hospital. However, $4 million of the line of credit was spent within the first two months, and administrators report that the remainder will last the hospital only six to eight more months. Purvis' "golden parachute" will be paid through the St. Joseph Health System in Orange, as was his salary -- $491,302, including benefits and other allowances for fiscal 2004, the most recent figures publicly available. The top money-makers on the local budget no longer employed at St. Joseph, according to public records, were McCrea ($306,314); Gorman ($282,042); and Orders ($239,012). Purvis did not return phone calls to the Journal for comment. No attempts were made to contact former CFO Galen Gorman, who has moved to Southern California to take a new job and be closer to family. Ann Orders was out of the area and unavailable for comment. Ellen Jackson would say only this: "I support the hospital. They are doing what needs to be done. I was with them 29 years." In essence, that was also Marc Levin's sentiment. Levin was the only former administrator who agreed to sit down for an interview following the layoff announcement. Using a somewhat macabre medical metaphor, Levin summarized his job termination in a final memo to staff dated Feb. 10. A line from the letter states: "Just as the heart stops pumping blood to the extremities to keep the body alive in extreme cold, we must sacrifice certain extremities to keep this hospital alive." Levin considers himself an arm of the hospital whose contributions, unfortunately, were not realized by turnaround firm Navigant Consulting and Joe Mark. "They saw an organizational chart. What they didn't see was all these different projects that I have done," he said, adding that he imagines he paid for his position many times over with cost-saving projects he implemented. "They don't have the time to look into that kind of depth when they're trying to do what they're trying to do." What they're trying to do is save close to $7 million in salary and benefits by cutting close to 140 employees, by Levin's estimation. Since he lost his job, the 56-year-old with salt-and-pepper hair and keen brown eyes has busied himself around his two-story Eureka home, remodeled the garage, and found a new position as compliance officer for Queen of the Valley Hospital in Napa, part of the St. Joseph Health System. Levin now lives there in an apartment. He and his wife, Teresa Levin, a nurse at St. Joe's, visit each other on alternating weekends. And while he says he has the right to be bitter about his situation, Levin claims he is not. (It should be noted that publicly disparaging the hospital would jeopardize his severance package.) Over and over, Levin drove home the point that he wants to see St. Joe's get better, and more than anything he wants the community to know it is crucial to get behind the hospital. Without philanthropic support, residents will not get the health care they might someday need, including cardiac surgery and neurosurgery -- two expensive specialties not offered elsewhere on the isolated North Coast. St. Joe's Heart Institute, Levin said, has never made money, but the hospital has kept it going anyway, because it believes it is important to provide that service. "There are a good number of people in this county that probably wouldn't be alive if they would have had to been taken out in an air ambulance," he said. It stupefies Levin to think that a Humboldt County radio station can raise over $50,000 for the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, or that Relay for Life pulls in hundreds of thousands of dollars for the American Cancer Society, but no one will step up to support the county's own. It would seem that for some, supporting St. Joe's is a bitter pill to swallow -- not only because the nonprofit's administrators have made a series of financial blunders in recent years, but also because of anti-Catholic sentiments and concerns over religious doctrine guiding reproductive rights. Levin thinks the Catholic stigma is unfair. Most vasectomies, he said, are done in doctor's offices and "probably all Catholic hospitals in this country do tubal ligations on a regular basis if a doctor documents that it is medically necessary and the doctors are pretty liberal on their documentation of that." And while Levin couldn't say exactly how the hospital got to this financial crisis, he offered a few thoughts, including that patient volumes at the hospital have been down. Part of that, he said, is because physicians who can't forgive St. Joe's for past mistakes choose to send patients outside of the area for treatment instead of referring them to Eureka. Other doctors "cherry-pick" from money-making services at the hospital by starting their own outpatient centers for things like urology, gastroenterology and outpatient surgery, leaving St. Joe's with cases that don't pay. - With money from its line of credit quickly running low, St. Joe's is trying to turn things around as quickly as possible. Whether it will be able to make the staffing cuts it has announced in the face of opposition from its nurses and medical staff is still an open question. Whatever the case, something has to be done to solve the short-term cash flow crisis that has all but bankrupted the hospital. Not everyone agrees that staff cuts would necessarily harm the hospital. In a phone interview , Dr. Lee Leer, former Chief of Staff at St. Joseph, said that efficiencies in housekeeping and other departments could actually improve patient comfort and satisfaction. "If they [the administration] can improve efficiency and also cut some staff, more power to 'em," Leer said. "I've certainly seen places where a lot of people were doing a little bit of work." That's the first step. There's still the question of how to best put the hospital back on its feet for the long-term. In an e-mail sent to the press last week, Mark said that the hospital is exploring several options, including a change in ownership. He said that the Sisters of Orange recently received an unsolicited offer for St. Joe's-Eureka. "While no decision to sell the hospital has been made -- nor will there be until we have thoroughly considered all available options --we are taking a `listening posture' and striving to consider all solutions with an open mind." Another possibility, he wrote, would be transfer of the hospital to a "community-based model," in which a public hospital district would form and take ownership of St. Joe's. Or the hospital's ownership could stay as it is, with the hope that donations and fundraising would be more successful in the future. In the meantime, though, with the hospital on the ropes, it is abandoning some of its traditionally combative relations with certain other members of the medical community. It is exploring how to better work with competitors. Dr. David Gans of Mad River Hospital met with St. Joseph administrators last week, and said that the hospital is weighing its options. "Whether they're going to stay a Catholic Sisters of Orange hospital or not at this point is up in the air," Gans said. "Could they possibly give the hospital in some fashion to the community and the Sisters of Orange stay up here with a foundation or some other charitable thing; will they keep it depending on how well they turn it around or not; can they turn it around; would some outside buyer be interested?" Gans said that previously, the hospital was "culturally incapable of sharing." Now, though, St. Joe's seems much more interested in collaborating with the small Arcata hospital on imaging work and recruitment of physicians. Mad River has even agreed to take over laundry duties for St. Joe's. And while Mad River administrators said there have been no offers made to buy their hospital, Dr. Gans says it would make sense to merge all three major local hospitals -- St. Joe's, Mad River and Redwood Memorial in Fortuna (a St. Joe's affiliate) -- and form a single, public community hospital district. "If we were a single entity, a single license number, it would put us in great shape with the government and the insurance companies to negotiate much better deals, more income, more health care for the people," he said. "We could cap Medical and Medicare for example in the county, get everybody insured, perhaps." It would also put an end to the technological duplication that already plagues the hospitals' coffers. St. Joseph has also entered negotiations to buy out Humboldt Radiology. The radiologists allowed St. Joseph's to review their financial information last week, after hospital administrators agreed that if they were to take over the radiology clinic, the doctors would still have control over several "deal-breaking" issues: recruiting and salaries, among them. The hospital would also have to promise not to buy the center simply to shut it down. "Their vision, I believe, is that they own the place," said Dr. Richard Greaney. "Our position is that we want to maintain ownership and/or control but we're willing to listen to anybody's proposals. " Meanwhile, Marc Levin, one of the first layoff casualties, will work in Napa. He'll look for future employment in Humboldt County and keep hoping that people here do the right thing, and support the hospital, the way he's found Napa County residents do for his new employer, Queen of the Valley. His final memo to staff summed up the situation: "Some people have told me my loss ... my fellow managers' loss, is a tragedy. Whether it is a tragedy or not remains to be determined. It is now up to you ... all of you to make this streamlined hospital work. If you fail, then yes, our sacrifice will be a tragedy." l COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

The

nurses shared their frustrations, and somewhat chaotically outlined

their fears. Most RNs said they aren't especially afraid that

they will be fired since the hospital is mandated by the state

to maintain patientto-nurse ratios. But they worried that

when housekeepers, clerks, dieticians and other staff are

fired en masse, a trickle-up effect will occur, and more work

will be piled on the caregivers.

The

nurses shared their frustrations, and somewhat chaotically outlined

their fears. Most RNs said they aren't especially afraid that

they will be fired since the hospital is mandated by the state

to maintain patientto-nurse ratios. But they worried that

when housekeepers, clerks, dieticians and other staff are

fired en masse, a trickle-up effect will occur, and more work

will be piled on the caregivers. While the majority of the layoffs -- an

estimated 10 percent or more -- will affect the lower paid and

non-clinical employees at St. Joe's, administrators have already

shouldered some of the burden.

While the majority of the layoffs -- an

estimated 10 percent or more -- will affect the lower paid and

non-clinical employees at St. Joe's, administrators have already

shouldered some of the burden.