|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | STAGE

MATTERS March 23, 2006

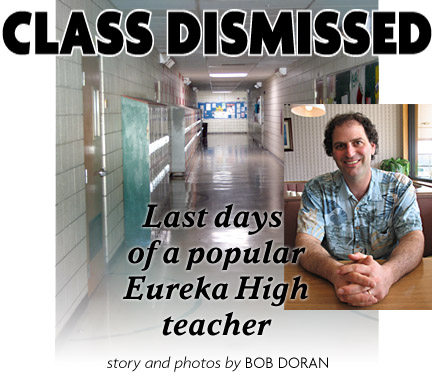

The school board meeting room was packed. Teens, parents and teachers filled every chair. More lined the wall in back. One girl held a pink tagboard poster decorated with stars and happy faces demanding, "SAVE Mr. Price!" There were other brightly colored handmade signs, the sort you'd see at a school sports rally, but instead of "Go Team!" messages, they were made to rally behind one of their teachers, Darin Price -- Mr. Price to the kids (pictured above). Until recently, he had been their chemistry and physics teacher, specializing in courses for the brightest kids, and he was much beloved. Suddenly, and for reasons no one could quite ascertain, he was gone. The decision not to rehire Price was officially

made on March 1, at an earlier meeting of the Eureka City Schools

Board of Education. Along with approving the adoption of new

courses in "Drama as Literature" and "Performing

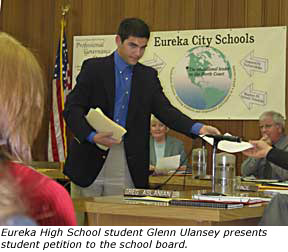

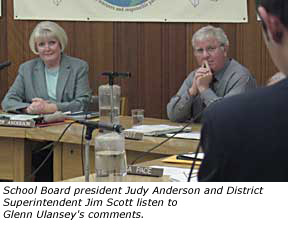

Arts Freshman And there wouldn't have been any discussion at the meeting two weeks later, either, if students, parents and other teachers hadn't come forward to protest the dismissal of the popular Mr. Price. The question of Mr. Price's employment -- the matter that stuffed the meeting room -- would be confined to the public comments period. His supporters were given 20 minutes only, with a limit of three minutes per speaker. As the meeting began, a stream of parents and students offered testimony about the importance of Price's teaching and the effect he'd had on young lives. Said Laura Hennings, a retired Eureka City Schools teacher and mother to Eureka High senior Colby Burns, "We have young people standing here, believing in the system, who are passionate about this teacher. I know that Mr. Price's leadership, his integrity and his honesty are not to be questioned. So, what is the motivation" for letting him go? Glenn Ulansey, a Stanford-bound senior and a student in Price's college-level Advance Placement (AP) physics class, presented the board with a petition signed by 295 students and several faculty members asking the board to reconsider its decision, and then read from a prepared statement. He spoke of students "impassioned" about their teacher and of responsibility: the teachers' responsibility to "provide a superior level of instruction," the students' responsibility to work diligently and the administrators' "absolute responsibility to advocate on behalf of the students of the school." Ulansey, wearing a sport coat and tie for the occasion, also spoke of honor and integrity. "We believe and trust that you have our best interest at heart," he read. "Moreover, you are all we have to rely on. Respectfully we implore you to further review this matter, and if you find that inappropriate and ill-advised actions were taken, you must do everything within your power to rectify them. Please show us that the system in fact works, that we have not been forsaken, that we can rely on you to do the right thing." The final speaker, another mother of one of Price's students, wondered aloud why he was pulled from his job a month and a half before the important AP test, which determines if the student gets college credit for the class. "Think about the students, the parents who don't know what happened, who are not allowed to know what happened. Please reconsider." The board didn't. That evening, despite the many pleas and the show of support for the teacher, the board upheld the decision to let Price go, in closed session, without comment. The most frustrating part of it, for devoted students and their parents, is that no one will ever know exactly why their school board decided to let an experienced, popular and apparently talented teacher slip through their fingers. A sign on the wall behind Eureka City Schools Superintendent Jim Scott listed "Professional Governance Standards" for the board of trustees. Standard No. 5 -- "Keep confidential matters confidential" -- pretty much ruled out any chance of shedding light on the matter.

On a sunny Saturday morning a couple of days before the meeting that finally sealed his fate, over breakfast at a McKinleyville restaurant not far from his home, Darin Price mused on Isaac Newton's First Law of Motion. "The first law is about inertia," Price began. "An object at rest stays at rest; an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by an outside force." He did not have the look of your stereotypical chemistry/physics high school teacher: A tangle of curls replaced the flat-top haircut, and he sported a pastel Hawaiian shirt (his usual classroom attire) instead of a white shirt with pocket protector. Despite the fact that his life path had just been knocked off course, he seemed upbeat, almost giddy as he looked back on his short time at Eureka High.

"There's personal satisfaction, I enjoy it, and it keeps you young working with these kids. And I think I make a bigger impact than I did teaching low-end college chemistry classes." Price, who is 42, said, "I thought I would probably retire between the ages of 55 and 60 as a high school teacher, but on Tuesday [Feb. 28] at 4:17, my whole world was changed." What was the force that altered Price's inertia at precisely that moment? A meeting with Eureka High Principal Bob Steffen, one that Price had every expectation would assure his future teaching Eureka's best and brightest. California law sets definite rules for hiring and retention of teachers. The first two years after a teacher is hired are considered a probationary period, during which time he or she can be removed from the job at the will of the administration -- without explanation. By the two-year point the teacher should have had four formal classroom observations and evaluations -- two each year. This was Price's last evaluation before receiving tenure and becoming a permanent school employee, a position that affords a teacher layers of protection against dismissal, including a hearing at which the school district must prove just cause. "I had expected [the evaluation] to be pretty much a formality that would [lead to] my recommendation for rehire and tenure next year," said Price. "We talked about 45 minutes, discussed all these things -- things I've done really well, things that could be improved. I've been there for about a year and a half and I've never had one negative comment. All my other evaluations have been stellar, so I was kind of shocked at the end of meeting. He said, `You know, Darin, I really like you, but I'm going to have to recommend we not rehire you.' I was shocked. There was no clue until that last second. That's what changed things for me. "I asked if he could tell me anything, something that might help me be a better teacher in the future elsewhere. He said he could not, that they're not allowed to by law -- they're afraid of litigation." Price noted that his write-up included a couple of negatives: His desk was messy and he admittedly was not always current with something called PowerSchool, an online record of student performance accessible by students, parents, teachers and administrators. But those seemed too minor to warrant letting go a science teacher with 17 years experience. Especially one with his record, Price argued: In the year and a half he taught at Eureka High, his students' scores on the standardized STAR tests showed marked improvement. Scores on the chemistry portion rose 10 percent over the previous year, placing Eureka High in the top 2 percentile in the state.

As per the school's policy -- and the policy of most any employer -- Principal Steffen cannot officially discuss personnel matters. But he gave his clearest statement of his reasons for Price's dismissal to Julio Miles, a reporter for Eureka High's newspaper, The Redwood Bark. "I can't make a comment on anything [as to] why he was not given tenure," he said. Pressed further, Steffen said the decision was based strictly on classroom observation. But he then conceded that other factors played a role as well. "Obviously there are things that I have to judge him on that are bigger than the curriculum delivery to the student. There are reasons why I make decisions, whether it's the non-reelect issue we're discussing here, or any policy. I do everything I can to make sure I'm making as balanced a decision as possible -- you talk to colleagues, students, parents. The ultimate decision is based on my direct observations.

What do Eureka High's teachers have to say about Price? Like everyone else, they can only speculate as to why he was not rehired. Byron Zinselmeyer, who teaches health and physical education at Eureka High, noted, "Depending on who you are, depending on the school you're at, being a probationary teacher is kind of interesting -- if you shake the boat too much, or make too many waves in the wrong direction, they don't have to keep you, and they don't have to tell you why. They can just get rid of you." According to social studies teacher Ron Perry, Price "didn't stay low; didn't accept the quiet role typical of a probationary teacher. [He] didn't play the game well -- in staff meetings he was really aggressive." In particular, Price was "vocal in criticism of the technology situation It was out of line, based upon his position as a probationary teacher." "The technology situation," specifically problems with the school computer network, weighed heavy on Price, and he said it got in the way of doing his job effectively. "That was a shame," he said. "Over the summer a virus got into the computer system at the high school. It made every computer in the science department unusable. In any modern physics class part of the curriculum involves using computers in many ways. We have something like $50,000 worth of equipment interfaced through computers that's integral to understanding things like the laws of motion, sound, every aspect of physics. We collect data and manipulate it through computers, [put it into] spreadsheets. With the system down, we were not allowed to use them. I was upset to have 40 computers in the science department not able to be used. It was bad, so I was aggressive in getting the computers fixed and online. "But," he insisted, "that was between me and the tech department, and it wasn't like I was impolite." Price actually proposed replacing the buggy computers out of his own pocket, with help from concerned parents. "Not using computers in a college-level AP course, well it was not even possible. I offered to replace the lab computers, buy 12 new computers, screaming remanufactured Dells, with a full-on warranty: $400 each. They would not let me purchase them; they had to be bought through a specific [supplier], and they were over $1,000 each. I wasn't willing to spend $12,000 for something I could get for $5,000. But if [the computers] were a bone of contention, it was never brought up."

Students and parents have another guess as to how Price fell from the good graces of the administration. They claim that other teachers disagreed with Price's teaching methods, in particular the fact that he rarely assigned homework in his chemistry classes. Speaking with pride about the rise in test scores during his time at EHS, Price suggested that "one of the things that bothered people was the reputation that my chemistry classes were, quote/unquote, `easy.' A lot of students will say that. They may say it's easy because I minimize homework. It was very controversial, part of my downfall. It may be hearsay, but students truly did like the class." Based in part on research he did with other teachers at Anderson Valley High, Price subscribes to the theory that additional busy work does not aid retention of information. In fact, he asserts, homework can actually have a negative effect on learning by increasing stress and leaving students working on their own without guidance.

In his interview with Miles, Principal Steffen did not dispute the fact that test scores went up during the short Price era, but he argues the statistical sample is too small to have real meaning. "Mr. Price certainly is in those classes that are at the top of the food chain, and I'm proud of them for having those kinds of scores," he said. "[But] he's only been here for a year, so it's hard to attribute [the changes to him]. We're very happy with the entire science department in terms of their performance, especially in physical science ... but I don't judge teachers based on their students' test scores, whether they're good or bad." For students in Price's AP physics class, "easy" is not necessarily a bad thing. "The reason it is easy is because of his way of teaching: He gets through to students," said Andrea Howard. "I've had science teachers that I've liked before, but nobody has made me like a subject and made me understand it as much as Price. He goes above and beyond the call of duty to make sure that his students get it, and if they don't, he'll find another way to explain it to you." Heather Price (no relation) deemed Mr. Price's unconventional methods of teaching "awesome," adding, "I loved the fact he didn't give as much homework [but] I always felt I understood the material. I think that the outpouring [of support] from students is just proof of how great a teacher he is." Colby Burns, a senior who took chemistry from Price and then went on to AP physics, had nothing but praise for his former teacher. "Every day he'd be in his classroom before school and at lunch. If you had any questions, he'd be more than happy to answer them. There are not many teachers that do that. The science budget was drained this year. He went out and spent his own money on lab equipment so we could do these labs for physics." It's clear that Price was highly esteemed by those who took his classes. Even Steffen, speaking with Miles, had to agree. "It's wonderful that Mr. Price has a following, people who respect him as a teacher and his competence, and I respect that," he said. "Obviously he's connected with some students."

On March 1, the day after he learned he would not be rehired, Price returned to his classroom. As Price put it, "I had to be honest with them, so I told them what had happened." His students did not take the news well, particularly those in his AP physics class. "I just feel betrayed," said Chris Scheffler, noting that he took two years of physics from Price, "and he interested me so much in [the subject] that I'm now majoring in physics, and that's how I got [accepted] into my colleges." Scheffler and his classmates Fred Hope and Glenn Ulansey decided they had to do something to reverse what they saw as a wrong decision. They wrote and circulated a petition in support of Price and made plans to present it at the next school board meeting. Word spread quickly around the school and hundreds signed. It's worth noting that the core of this uprising was what might seem an unlikely group of rebels: students at the top of their class academically, all of them college-bound, and for the most part candidates for top schools. "The best and brightest" was how one proud mother described them.

He insists that he played no part in rousing the students. "It was spontaneous compulsion they felt," he said. "From what I've been told, they thought something wrong had happened and they wanted to do the right thing, to make a difference, to right a wrong. I'm proud of them for doing it, but I did not encourage it, I did not initiate it and I did not expect it." "He told us he wasn't going to be rehired," Colby Burns recalled. "He said he figured sooner or later there'd be rumors. He wanted us to know the facts right away. I'm not sure if the administration was too happy about that, but I think it was the right thing to do. But he never told us to do anything to help him out, to write the petitions. The students decided to do that on their own." Word that the students were circulating petitions in support of Price got to the administration quickly. Before the week was out, Price was asked to meet with Associate District Superintendent Greg Aslanian. While the administration denies that the petition was the direct cause, they suddenly wanted Price out -- immediately. "The district came to me, they said they figured this was devastating and it would probably be best for me if I would move on with my life and take some time to readjust," said Price. "Officially I'm on [paid] administrative leave until the end of the school year. It was a mutually agreed upon decision." According to Aslanian, pulling a teacher out of his classes like that is not unprecedented. "For some people it's fine to finish out the end of year, for some people it works out better for both parties not to, and that was the case here," he said. "When I spoke with him he was pretty pleased. It gives him an opportunity to move on. I'm not going to second-guess him, but I think if you asked him about the separation, he'd probably agree it was something that was mutually agreed to." Price did consent to the early departure, but only after specific conditions were met. The final weeks of the school year are crucial, particularly for AP classes where the score on a year-end test is all-important. "One of my biggest requirements was that the students would not get screwed," said Price, "that they get a highly qualified teacher in these specific subjects. I did not want to see an endless stream of different substitute teachers [taking my place]. I made a commitment to these kids." Price suggested that the district contact Weldon Benzinger, the science teacher he had replaced. Benzinger agreed to come out of retirement to take over Price's classes for the duration of the school year. "He's sacrificing a lot in my opinion, coming into a difficult situation because he cares about these kids," said Price. "That requirement being met took a lot of weight off my shoulders. I knew the kids were in good hands. So I agreed to go on administrative leave, without coercion."

Asked if the decision not to rehire Price was set in stone, Principal Steffen had told Miles that despite any protestations from supportive students and teachers, the determination was essentially irreversible. "It's the nature of the beast," he said. "Mr. Price and I are locked in this dance. He can't appeal [the decision], unless he finds something I did incorrectly." As it turns out, it's likely there was an irregularity in the process leading to Price's non-reelect. According to contract rules he should have had four formal evaluations in the two years he was employed. "I observed him first," said Steffen, "and Mr. Faeth [an administrator who has since moved on to another district] was scheduled to do his spring evaluation. I haven't talked with Mr. Faeth. I didn't see the paperwork, the paperwork gets sent to the district office, so I'm not completely sure [if it happened]." But according to Price, Faeth's observation never happened. After talking further with a lawyer and with the union, he determined that he could in fact file a grievance, "but they'd still have the right not to rehire me, even with the technicality, so why fight it if there's no change in the outcome? It's still sad, though. Maybe if I'd had a little more feedback I might have had some indication that they thought there was a problem." "There are definitely shortcomings in the process," Steffen conceded. "We're definitely too busy to monitor our teachers as effectively as we would like. The school system does not get enough money to do all we'd like to do." Ben Henshaw, the union rep for Eureka High teachers, sees Price's departure as a shame. "It's not like there's [honors] chemistry teachers knocking at the door," he said. "There's not a lot of teachers coming in, and you have this teacher with a passion for teaching, who's very personable with students and [let him go], I think it's a travesty. I think it's criminal, on the verge of malicious." As Price's supporters filed out of the March 15 school board meeting, Glenn Ulansey was still feeling moderately optimistic. The school board had moved on to business as usual, a report on the budget and later on another closed session including discussion of personnel matters. "We would certainly hope that all the students being behind him would mean something to the administrators and school board members here," Ulansey said. But even though it might not have had any effect, he was still glad he spoke up. "The outcome may not change, but I think it will make them reevaluate their decision and question whether or not they made the right one." The next day, the board's president, Judy Anderson, would say only that Price's dismissal was upheld. "The board decided to let the vote stand," she reported the following day. "I can't foresee it coming up again." Two days after the school board meeting, Price was driving his car out of McKinleyville on his way to meet a client who might be interested in doing business with Baypoint Mortgage, his new employer. Over his cell phone, he spoke with optimism about his new career in real estate, but it was clear he already missed teaching. "I've been encouraged to go back into it at HSU," he said. "I submitted my resume and a letter of intent to get into the temporary pool yesterday. I'm assuming I'll get work if there's labs or classes they need me for that fit into my schedule." Would he like to get back to teaching full-time? "Maybe, but not high school -- not high school." Eureka High School senior Julio Miles contributed to this report. COVER

STORY | IN

THE NEWS | STAGE

MATTERS Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Selective"

and accepting the "Lice Busters Project Grant," the

board approved item No. 26 on the consent calendar: "Non-Reelect

of Certificated Personnel." The bureaucratic term "non-reelect"

boiled down to this: Mr. Price had lost his job. The item passed

without discussion.

Selective"

and accepting the "Lice Busters Project Grant," the

board approved item No. 26 on the consent calendar: "Non-Reelect

of Certificated Personnel." The bureaucratic term "non-reelect"

boiled down to this: Mr. Price had lost his job. The item passed

without discussion. Price

came to the school in 2003 after teaching chemistry and running

chem labs for eight years at Humboldt State University. He took

the place of a retiring teacher seeking something he had experienced

earlier in his career, when he taught high school at Anderson

Valley High in Boonville: a sense of importance.

Price

came to the school in 2003 after teaching chemistry and running

chem labs for eight years at Humboldt State University. He took

the place of a retiring teacher seeking something he had experienced

earlier in his career, when he taught high school at Anderson

Valley High in Boonville: a sense of importance. "Often

times administrators get blamed by students for certain policies

that really are born out of teacher input and staff input. And

that's OK, that's why we get the big bucks."

"Often

times administrators get blamed by students for certain policies

that really are born out of teacher input and staff input. And

that's OK, that's why we get the big bucks." "So

if I have students who enjoy this class with no homework, yet

they excel to the absolute pinnacle in the state of California,

the 1 or 2 percentile at the top, and almost no one dropped the

class -- well, that's my goal. I succeeded with flying colors.

Is that a problem? I think if I was an administrator and I saw

something like that, I'd say that's a model I would want my teachers

to observe. Was that part of their decision to let me go? I don't

know."

"So

if I have students who enjoy this class with no homework, yet

they excel to the absolute pinnacle in the state of California,

the 1 or 2 percentile at the top, and almost no one dropped the

class -- well, that's my goal. I succeeded with flying colors.

Is that a problem? I think if I was an administrator and I saw

something like that, I'd say that's a model I would want my teachers

to observe. Was that part of their decision to let me go? I don't

know." "I've

never seen such an outpouring of support from students and teachers

for anyone in my 18 years teaching," said Price, describing

it as "a humbling experience."

"I've

never seen such an outpouring of support from students and teachers

for anyone in my 18 years teaching," said Price, describing

it as "a humbling experience."