|

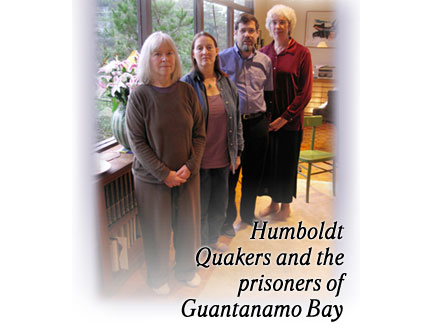

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | THE HUM | CALENDAR January 5, 2006From the left, Margaret Thomas Kelso, Andrea

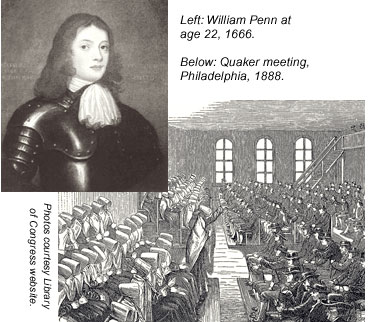

Armin-Hoiland, Dr. Fred Adler and Carol Cruickshank. by WILLIAM S. KOWINSKI AT THE CENTER OF A LARGE, airy room in an Arcata home -- so large a room that a grand piano at its far end is conspicuous but not dominant -- six Humboldt citizens gather in a circle on an oatmeal rug. With afternoon light spattering off the leaves of trees beyond a wall of windows, or in a cocoon of lamplight against the winter evening darkness outside, they talk about what they've done to further their agenda, and consider their next steps. They spend a large part of their time together -- perhaps 35 minutes of it -- in silence. They've been meeting like this at the home of Dr. Fred Adler and Carol Cruickshank at least once a month for a year now. They are trying to do something that's never been done: To go with official permission to the Guantanamo Bay prison on the island of Cuba for a week, to visit with the prisoners and their captors, to offer comfort and bear witness to what both groups are enduring. Guantanamo is where the U.S. government has brought men and boys from 38 countries to be interrogated and held as part of the "war on terrorism." That these six comprise a tiny group of ordinary citizens in a forlorn corner of the country would seem to make their attempt even more futile. But their efforts have already involved Rep. Mike Thompson, the U.S. Defense Department and hundreds of other people in California and across the country. If for no other reason, they are taken seriously for one simple fact: They are members of the Humboldt Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, or the Quakers. As Quakers, they can call upon the credibility of several centuries of active commitment to international peace and social justice, including a Nobel Peace Prize. The nature of their commitment is also informed by Quaker tradition. They don't proselytize for any religion or any country. They oppose war and cruelty, but in past conflicts, the victims on all sides had their help, and all sides learned of their value. They aren't just social activists or only spiritual. Their presence and their process is a unique combination of both. From Persecution to the Peace PrizeWhen I was growing up in western Pennsylvania I knew two things about Quakers: With the leadership of William Penn they settled my state, and they made breakfast cereals shot from guns. One of those two turned out to be true. A new -- and newly banned -- "Nonconformist" offshoot of the official Anglican religion in 17th century England, Quakers got their popular name during the trial for blasphemy of the man usually described as their founder, George Fox. Fox favored the name "children of light," but his followers were dubbed Quakers because in early services they trembled with the knowledge of the divine presence. Fox's contemporary, William Penn, embarrassed his wealthy and powerful family by becoming a Quaker and getting thrown out of Oxford University because of it. When Penn was put on trial in London, apparently for preaching, he was denied the right to see the charges. When the jury acquitted him, the Lord Mayor put him in prison anyway, along with the jury. They eventually won the right of all English juries to be protected from such punishment.

Early Pennsylvania Quakers helped establish the principle of religious tolerance in America, and with their bedrock belief in equality (they at least tried to deal fairly with American Indians, buying rather than just stealing their land), they influenced the formation and principles of the United States. Back in England, nine Quakers and three Anglicans formed a committee in 1787 to abolish the British slave trade. With a sophisticated campaign that included petitions, posters, newsletters and consumer boycotts -- all new political tools at the time--they succeeded in making slavery the central moral question of the time, and within 20 years, they achieved their goal. One of their earliest statements of principle (called "testimonies") was against warfare. Individual Quakers decide how they will honor this testimony, but their beliefs have been recognized as grounds for conscientious objection since the Civil War. In many instances, refusing to bear arms was only the beginning of a commitment to peace. In World War I, Quakers organized relief efforts for refugees and other victims of the war, principally through new organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee. They were so effective in combating hunger and disease that after the war ended, Herbert Hoover (then running the American Relief Administration) gave the AFSC the task of feeding the undernourished children of Germany, as well as helping to stem famine and epidemic across Europe. Some Quaker draftees during World War II did public service while in CO camps, while others served as ambulance drivers and medics on the battlefield. Quakers advocated for Japanese Americans interred during the war, and helped survivors of Nazi concentration camps afterwards. Again they helped to bring Europe back from immense devastation. A year after the end of a war that killed an estimated 65 million people, the American Friends Service Committee and the Friends Service Council of London accepted the 1947 Nobel Prize for Peace on behalf of all Quakers. From at least the early 19th century, Quakers also have provided comfort and relief to prisoners. It was their prison work that the Nobel Prize committee cited as their most characteristic. "It is the silent help from the nameless to the nameless," said its chairman, "which is their contribution to the promotion of brotherhood among nations... " From Humboldt to GuantanamoFor a few years after 9/11, Americans knew little about what was going on at Guantanamo Bay, except that prisoners suspected of involvement in terrorism were taken there from various countries as prisoners of war, outside the jurisdiction of any U.S. court, and kept indefinitely and without charges. Then stories of inhumane treatment, torture and interrogation techniques banned by the Geneva Conventions began circulating, finally reaching the American media. "When I started hearing about Guantanamo Bay prison, I just had the feeling that we should go there," Carol Cruickshank said. "But I guess I was hoping that somebody else would do it. I just tried to ignore the feeling." Then an echo of another history changed her mind. Carol Cruickshank is a nurse and midwife employed at St. Joseph's Hospital, where she is currently training Latino women to conduct prenatal and parenting classes in Spanish and to do home visits and support, as part of a program called "Paso a Paso" (Step by Step). She and her husband, Dr. Fred Adler, came to Humboldt County in 1986. He is an emergency room physician at Redwood Hospital in Fortuna and other area hospitals. He also practices at the K'ima:w Medical Center in Hoopa. Though they each had earlier exposure to Quakers elsewhere, it was at the urging of local friends that they attended their first Quaker Meeting in Humboldt in the late 1980s. They've been part of that community ever since. But it wasn't anything specifically Quaker that convinced them to take on the Guantanamo project. It was something from the past of Adler's family. A Belgian author named Marc Vershooris got in touch with Adler about a book he was writing on World War II victims of the Holocaust in the city of Ghent, Belgium. Fred Adler's family in Vienna had all made it to England except for one aunt who stayed in Ghent. She was one of the Jews transported from there to Auschwitz, where she was murdered by the Nazis. Fred Adler was able to provide some letters and other artifacts, and the author in turn discovered more about Adler's aunt than he'd known. Both Adler and Cruickshank attended the exhibition celebrating the book's publication, and Fred played some music he'd written. But the parallels between injustice then and now were becoming too powerful to ignore. "The Europeans were trying to come to terms with that history and deal with it," Cruickshank said, "and here we were ignoring that history, and going in the direction of repeating it. "So I went to Quaker Meeting here in Arcata and told people I thought we should go to Guantanamo Bay prison. We started meeting and worshipping together in January, and out of that group, six of us decided that is what we should do." The six are Fred and Carol, the legendary Dr. Richard Ricklefs of Hoopa, Karin Salzmann (a retired Montessori teacher from Trinidad), Andrea Armin-Hoiland (an instructional assistant for primary schools from Arcata) and Margaret Thomas Kelso (associate professor of theatre at Humboldt State University from Arcata, and my partner. Apart from my keen reportorial instincts, this is how I first learned of this group.) "For me, it's felt very much [like] a shared leading with the other five people," Cruickshank said. "I felt that if the United States was going to be torturing people in our name and with our tax dollars, we should be there to try and comfort the prisoners who are being tortured. But one of the wonderful things about Quakerism is the belief that both sides of the conflict are in need and are damaged, so the other Quakers in the group have really reminded me that we need to provide comfort to the U.S. soldiers at Guantanamo as well." Their first plan was to ask Humboldt's Congressman Mike Thompson to go with them to Guantanamo. They got a meeting with Thompson at his Eureka office in June. By that time, Amnesty International had issued its lengthy, meticulously documented report, describing numerous violations of human rights and international law at Guantanamo, including testimony from FBI observers that they'd witnessed torture there. Amnesty, the American Civil Liberties Union (which had uncovered the FBI reports) and the International Red Cross (the only organization that's ever been permitted to see prisoners at Guantanamo) all had called for Guantanamo Bay prison to be shut down. Shortly afterward, the Pentagon announced it had awarded a $30 million contract to a Halliburton unit to build a new detention facility and security perimeter at Guantanamo. All six members of the Guantanamo group attended the meeting with Thompson. They had divided up the relevant information and each prepared a presentation on their part of it. "But we didn't have to do much of that," Cruickshank recalls. "He was very well informed on the issue." Thompson declined to accompany them to Guantanamo, but told them he would find out if it would be possible for them to go. They soon received a copy of a letter Thompson sent to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld on their behalf. "I was surprised when I saw it," Fred Adler said. "I didn't realize he was going to help us in that way." "The Quakers have provided religious witness for peace since 1660," Thompson's letter said. " In major conflicts around the world, Quakers have been present to listen and provide spiritual relief for all sides engaged in conflict." He asked that they be permitted access to prisoners inside. They didn't receive a reply until late September. The letter signed by an aide to Rumsfeld described detentions at Guantanamo as "ongoing military operations," for which access is "generally limited to those with an official purpose connected to the global war on terrorism." Their request was denied. The group met a few days later. "The sense of the meeting was that this wasn't unexpected," Carol said, "and now we at least have something to respond to." Commitment to HopeAs the Guantanamo group marks one year since it started, its members consider new concerns and new approaches. Some 200 Guananamo prisoners have gone on hunger strikes to protest their indefinite incarceration, and more than 20 have been fed forcibly through feeding tubes while they are strapped down. This forced feeding has become an ethical issue for the international medical community, and since two of the local group are doctors, it's become another area of activity. Then came the revelations of secret prisons and "renditions" to foreign prisons known for torture. "All of us are concerned that the problem is if anything larger than we thought a year ago," said Cruickshank. "We know there are some youngsters who were maybe 14 when they were first imprisoned. They have basically grown up at Guantanamo." According to United Press International, there are at least nine juveniles among the detainees. Even the apparent good news of the law banning torture that Congress passed recently has alarmed human rights organizations -- they say it contains provisions that could make torture during interrogations even more likely at Guantanamo. As 2005 ends, the U.S. government admits to holding 650 prisoners at Guantanamo. UPI has determined they come from 38 different nations. "Our sense of urgency about being in Guantanamo is persisting," Cruickshank said, summing up the sense of their final meetings of 2005. "We're going to keep knocking on as many doors as we can to find access into the prison. The group is clear that this is a long-term commitment and we're willing to keep working on it until we're allowed to go in, or even better, that the United States decides to dismantle this system of prisons." Still, when even the United Nations can't get into Guantanamo, their prospects are remote. After their last meeting of the year, Andrea Armin-Hoiland talked about what settled her doubts. "I feel really strongly that we have to do it for the kids. Our kids hear us say `Do the right thing,' and then they're watching: Are we doing it or not? I feel we will create real hopelessness if we just give up without trying, however crazy it is. My kids can do without a lot, but they can't do without hope." Since their first contacts with other Pacific Coast Quakers at a regional meeting were encouraging, the group will now emphasize reaching out to other Quaker groups, as well as other political leaders, such as California's U.S. senators. They're also writing directly to Guatanamo's chaplain. But unlike most other groups involved in social causes, their meetings will continue to include long periods of silence. I witnessed one meeting along with a Montreal-based filmmaker, Carlos Ferrand, who was filming it for a documentary called "Americano." After some discussion, the group paused for a 35-minute period of "worship," which a Quaker pamphlet describes as "silence and expectant waiting" in "mystical communion, individual meditation or prayer, with spoken ministry only as Friends may feel led to share their insights and messages." So for awhile, Ferrand's sound engineer kept his boom mike hovering over the group, recording the sound of silence. Eventually each person did feel moved to speak. They contemplated the mental and emotional costs of their work, the need to accept the suffering of others -- that life goes on, yet they can't ever accept what was happening in Guantanamo. They must find a balance, a way of acting with equanimity. They had to find a way to be compassionate without closing down, without allowing it to break their hearts. They talked about what a rabbi said after 9/11, that in even all that sorrow they had a commandment to be joyful, to keep their hearts open. How was that possible? Perhaps, one said, by turning anger and despair into joyful action. It is this approach of an examined inner life combined with exterior action that perhaps best characterizes Quaker activism. "This is different from anything any of us has ever done," Andrea Armin-Hoiland said. "What helps is the half or third of our time together in silent worship. That is how we are figuring out what to do, much more than talking about it." The Quaker Way in HumboldtEvery step of the way, the Guantanamo group has been nourished by the support of their Humboldt Quaker community. The Humboldt Friends "Meeting for Worship" occurs Sunday mornings in the Subud House, a small, wood frame building in the Arcata Bottom. Under the skylight in a large room, three comfortable old sofas and a row of chairs face each other. Those attending may sing a few songs before worship, especially if children are present. For instance, one called "George Fox," with a tune similar to the Shaker hymn, "Simple Gifts:" "Walk in the light wherever you may be/In my old leather britches and my shaggy shaggy locks/I am walking in the glory of the Light, said Fox!" But they are just as likely to sing a few verses of "Yellow Submarine." Then worship for an hour, followed by news of interest to the community and perhaps discussion of thoughts they had that didn't seem to quite meet the test for sharing during worship. "Not everyone is comfortable with Quakerism, " observed Leslie Zondervan-Droz, administrative analyst at Internews in Arcata, and currently "clerk" in charge of official business for the Humboldt Friends. "It's a difficult approach. There isn't a leader to answer your questions. There's a lot of personal responsibility for your practice and your spiritual life." She was attracted to Quaker worship by its similarities to the Northeast Woodlands tribal beliefs passed down to her as a child in Michigan. "For me, Quakerism is a process," she explained. " It gives you tools for working on your connection with the spirit. ... Some people find that the Christian heritage in Quakerism is very important, and for me it's irrelevant. What feels very comfortable to me about Quakerism is that there isn't a dogma, and the emphasis is on connection with the spirit, and being responsible to the spirit. That's very much the sense of the spirit in Northeast Woodlands culture -- you have this responsibility, and you are a spiritual being." "I refer to myself religiously as a Native American Quaker, and I've known other Quakers who refer to themselves as a Catholic Quaker or a Jewish Quaker," she said, "because they bring that culture and cosmology to the Quaker practice." But without leaders or dogma, a lot of emphasis is placed on the Quaker community. "Because it's those other people who help guide you in your spiritual life," she said. "In the community is where you can act on your faith."

Adler sought draft and C.O. counseling at the Peace Center in Palo Alto where he grew up. "I remember the Quaker woman who was the main administrator. She was a real bulwark. She was there every day, and held the place together." Left: Dr. Fred Adler. Photo by Bob Doran. Cruickshank had a similar experience as a student at Kalamazoo College in Michigan. "We had a weekly silent vigil on Wednesday afternoons at the draft board," she recalls. "Most of us were young and maybe not totally reputable looking, but every week a Quaker elder came and stood with us, looking very prim and proper in her dress. She was there every week, and she was a real comfort, to have an adult there who stood with us." Their social and political activism also helped determine their choice of career. "The reason I went to nursing school was the fear that I wouldn't be able to work in the states because of my politics," Carol said. "Now I have enormous freedom to do political work and speak out because I'm very employable. Being in health care gives you that freedom." Fred Adler studied classical piano until early in his college education. He still studies composition and continues to play -- he and pianist Felicia Oldfather will perform a benefit concert on Jan. 15 at HSU for the GI Rights Hotline, in which he is also active (see "Answering the call," Oct. 6, 2005). He switched to medicine from music for the usual practical reasons -- the uncertainty of a musical career -- but also to enhance his effectiveness in social causes. "There were years when I struggled with it," he admitted. "It wasn't my first choice. I would rather be doing music than any of these other things. But I think I'm a good doctor, and now I'm even happy as a doctor. It's been very good to me, and it gives you a role that a lot can be done with, aside from the medical practice itself. As a doctor, you have status. When we went to talk to Mike Thompson, it helped that we had two physicians in our group. It helps you get in the door." On any given Sunday, the Quakers probably form one of the smaller congregations in Humboldt. The Humboldt Friends have a mailing list of 40 families and individuals. There are usually around 15 people at the Sunday Meeting for Worship. But Meeting is open to everyone, and sometimes it attracts curious students from HSU, or Quakers from other places who are visiting Humboldt. "And there are certain times, like when we're about to get into a war, when a lot of people come to Meeting who don't usually come," Fred Adler observed. "Yes," Cruickshank agreed. "We know to put out extra chairs that day."

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | THE HUM | CALENDAR Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Penn

secured two large grants of land in America from Charles II (who

owed his family money) and founded a colony where Quakers would

not be persecuted -- and unlike some other colonies established

by unpopular sects, neither would adherents of other religions.

He called it "Sylvania" (Latin for lots of trees) and

Charles added the "Penn."

Penn

secured two large grants of land in America from Charles II (who

owed his family money) and founded a colony where Quakers would

not be persecuted -- and unlike some other colonies established

by unpopular sects, neither would adherents of other religions.

He called it "Sylvania" (Latin for lots of trees) and

Charles added the "Penn." While Zondervan-Droz

was drawn most strongly to Quaker spirituality, it was Quaker

social activism that attracted Adler and Cruickshank, during

the Vietnam War.

While Zondervan-Droz

was drawn most strongly to Quaker spirituality, it was Quaker

social activism that attracted Adler and Cruickshank, during

the Vietnam War.