Roads and Redwoods

Inside the big fight over the Richardson Grove project: Part I of II

By Cristina Bauss[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Mary Keehn founded Cypress Grove Chevre three years before Maxxam descended on Humboldt County.

In 1983, Keehn, a top breeder of Alpine dairy goats, embarked on a new venture: making cheese from their milk, in a time when the American market for goat cheese was extremely limited and virtually no one in the United States was producing it. Working in her home kitchen, she developed techniques for making mild cheeses, both soft and hard, which were very different from the strong, "goaty" European products that then dominated the tiny U.S. market. Business was slow for the first few years, a time during which Keehn and a handful of others pioneered what is now a multimillion-dollar industry. Today, Cypress Grove is world-renowned. Its innovative products have won a number of blue ribbons in international competition, and its most famous cheese, Humboldt Fog, has become a household name.

In 1985, Texas billionaire Charles Hurwitz set his sights on the Pacific Lumber Company, a family-operated enterprise that had, for well more than a century, provided a way of life that remained but a memory to most Americans: solid, well-paying jobs with good retirement benefits, in a mill town where the company paid for everything from public services to park maintenance to scholarships for high-school students. Hurwitz liquidated the company's priceless stands of old-growth redwoods, methodically destroying, in less than two decades, everything the Murphy family had so carefully constructed over a hundred years' time. The forest, of course, had stood for milennia -- and Hurwitz's actions spurred a series of lawsuits by the Garberville-based Environmental Protection Information Center, litigation that ultimately resulted in watershed victories for the environmental movement at large.

For many people who remember the days before Maxxam, Cypress Grove and other businesses like it represent hope for the future: homegrown enterprises that provide local jobs and, in some cases, brand names associating Humboldt County with something other than the timber wars or marijuana. But their success is dependent on their capacity to export their products, an endeavor that costs more here than in most other places this size. To remedy the situation, the California Department of Transportation embarked on a series of projects that, as mandated by the federal Surface Transportation Assistance Act (STAA) of 1982, were designed to facilitate access for commercial-sized trucks through "terminal access routes" such as U.S. Highway 101.

In northern California, the last bottleneck on 101 is through Richardson Grove State Park, just north of the Mendocino county line. Proclaimed by some as the entrance to the fabled Redwood Curtain, the grove is a gateway that many environmentalists and anti-development activists would like to keep locked. And this is why, 20 years after Redwood Summer, EPIC and others have taken on a new fight -- one that raises difficult questions about the future of Humboldt County, the divisions among its residents, and the direction of the local environmental movement in the post-Hurwitz era.

A Short Primer on Trucks

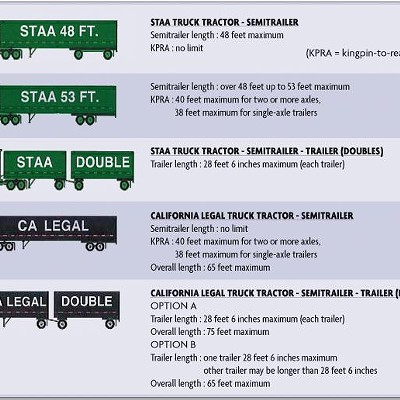

From the junction of U.S. 1 at Leggett north to Benbow, only California Legal trucks may pass. A single-trailer truck is limited to a total length of 65 feet, while a double-trailer truck can be as long as 75 feet. A truck with two shorter trailers is less prone to "off-tracking," which is the tendency for the rear tires to follow a shorter path than the front tires when turning. This is what puts truck trailers over the double-yellow line when rounding tight curves. Off-tracking is the key to the Richardson Grove dilemma -- not speed, as is widely believed.

Total weight limits are the same for both Cal-Legal and STAA trucks, regardless of length -- 80,000 pounds maximum. But there are also limitations on the kingpin-to-rear-axle length, which are different for Cal-Legal and STAA trucks. These affect both the weight that a truck can carry -- when the KPRA length is reduced, so is the load -- and the tractor size. Therein lies the problem: The length limit in the grove precludes the entrance of many STAA-standard trucks, which often have a conventional tractor with a sleeper cab and a 53-foot trailer (longer trailers are used to maximize freight and minimize costs). In order to meet Cal-Legal limitations, a conventional tractor with a sleeper compartment can only have a 48-foot trailer; conversely, a truck with a 53-foot trailer can only have a "day cab," a model without a sleeper.

If a trucker realizes he can't get through Richardson Grove, or gets an over-length ticket from the California Highway Patrol, the company whose load he's transporting must pay a local outfit to meet him at South Leggett and switch the tractor for a shorter one. After the load is delivered, the tractors are switched back. According to Vince Thomas, Director of Logistics and Distribution for the Arcata-based Sun Valley Group, switching tractors at South Leggett costs the company $1,000 each time it has to be done.

Adding Curves to the Road?

"There are so many misconceptions as to what this project is," Project Manager Kim Floyd said on March 11. "We're actually adding more curves to the road, which seems counter-intuitive." The bulk of the work would be done between mile post markers 1.35 and 1.40, where the roadway is essentially being moved over 17 feet: What is now the southbound lane would be removed and restored to natural soil; what is now the northbound lane would become the southbound lane; and what is currently an embankment on the east side of the highway would be filled in and paved over to become the northbound lane. The completed roadway in that section would be up to two feet wider to provide shoulders. The curve would actually be wider and more sweeping, to accommodate two STAA trucks traveling in opposite directions.

In several other parts of the mile-long project area, shoulders would be added or widened, and bicycle awareness signs are planned throughout. At the northernmost tip of the project area -- outside of the park -- a retaining wall would be constructed on the east side of the highway, just north of Singing Trees Recovery Center. An earlier plan, which was scrapped due to protests from both Singing Trees and project opponents, would have included the construction of a 300-foot-long, 17-foot-tall wall across from the center, on the west side of the highway. And while the Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) indicated that 89 trees were slated for removal, the number has been reduced to about 40 in the final EIR. Of those, 30 are within the park, with the largest being a 24-inch tan oak.

If approved, funding for the project will come from the State Highway Operation Preservation Program, or SHOPP; the estimated total cost is now $7 million, including the $1.1 million that's been spent to date on the DEIR and EIR.

Project opponents argue that Caltrans' stated primary reason for the project -- safety -- is disingenuous. "There is no problem with safety in the grove," Kerul Dyer, Outreach Coordinator for EPIC, said during a Feb. 24 forum held at the Garberville Veterans' Hall. "The DEIR claims that the road needs to be widened because of collisions. So we went ahead and reviewed the CHP reports, and this is what we found: For a five-year period, there were only six accidents involving trucks in this stretch of 101. Two of those occurred within one minute of each other; only one involved trucks going in opposite directions; and according to the information we reviewed, there has not been one truck accident in the grove since June 21, 2005."

Floyd's response, when she spoke with the Journal on March 11, was that the project is considered "an operational improvement that will have safety-related benefits." As made clear in the DEIR, the problem isn't so much the safety of the Grove now, it is the safety of that stretch of road if or when it fully opens to STAA vehicles. She added that safety concerns extend to recreational vehicles as well. Both trucks and RVs routinely hit some of the trees in the grove, as evidenced by battle scars on the trees and the detritus on the side of the road: side-view mirrors smashed to pieces, broken reflectors, and even RV steps half-buried in the duff.

Project opponents also question why there are no written regulations for STAA-accessible roadways. "There is no written standard as such for STAA trucks," Julie East, Caltrans District 1 Public Information Officer, wrote in an e-mail dated Nov. 18, 2009. "What we use are truck turning templates [which] show the spatial requirements for STAA trucks." The templates are found in the state Highway Design Manual; for STAA-standard trucks, total lengths incorporated in the designs run from 64 feet for the shortest single-trailer truck, to 81 feet for the longest double-trailer model.

To Cut or Not To Cut

While the possibility of longer trucks is a concern of Caltrans' opponents, it's tangential to the two main arguments against the project: the potential impacts to the environment, and the potential of further big-box development in Humboldt County. Environmentalists' major concern about the project is neatly summarized on page 83 of the DEIR: "Long-term impacts to the trees resulting from this project include placement of impervious material, placement of fill over the roots, changing drainage patterns, and compaction. Short-term impacts from construction can affect tree roots from such activity as soil disturbance, excavation, compaction, cutting roots, and exposure to fuel and oil from leaky equipment.

"Of most concern," the DEIR continues, "is construction activity that occurs within the structural root zone of the trees for both long-term and short-term impacts. The structural root zone is a circular area, with the tree trunk at the center, with a radius equal to three times the diameter of the tree trunk measured at 4.5 feet above the ground level. There would be construction activities that occur within the structural root zone of approximately 30 redwood trees ranging in diameter from 18 inches to 15 feet."

The idea that the roots of old-growth redwood trees are going to be cut has horrified project opponents. "It is basic redwood science that redwood trees have interrelated shallow root systems," Dyer wrote in an e-mail dated March 24, in response to questions submitted to EPIC Executive Director Scott Greacen and Staff Attorney Sharon Duggan. "We cited to that in our comments on the DEIR. Caltrans maintains that it can cut roots, compact soil and place fill on the roots of these ancient trees with no impact. Unfortunately, Caltrans provided no science to support this position, which is contrary to basic redwood science. The public does not have the burden to develop studies, or for that matter, find studies. Caltrans had that burden in the DEIR, and it failed to satisfy that burden." (Caltrans actually does acknowledge that there might be both long-term and short-term impacts, but it cannot say what they might be.)

The reason Caltrans cannot satisfy that burden is simple: There are no studies on the impact that cutting roots, compacting soil and placing fill on roots has on redwoods. Project supporters contend that the very fact that the trees lining the roadway are healthy challenges opponents' fears -- especially given that the construction methods used when the road was first built, in 1915, were undoubtedly much less sensitive than what Caltrans is proposing. EPIC couldn't give a clear response about the apparent health of the trees next to the road: "What we see in Richardson Grove along Highway 101 is a balance in nature," the March 24 e-mail read, "a balance that has been successful for nearly a century. What Caltrans fails to justify is why that balance must be placed at risk."

Caltrans argues that it will have a certified arborist, Darin Sullivan, overseeing the project, and that several mitigations listed in the DEIR are designed to offset any potential impacts to redwood roots. They include the "use of an air spade while excavating the soil within the structural root zone of redwood trees"; "use of a sharp instrument in order to promote healing" for "roots less than two inches in diameter"; and the use of "Cement Treated Permeable Base (CTPB) to minimize the thickness of the structural section, provide greater porosity, minimize compaction of roots and minimize thermal exposure to roots from Hot Mix Asphalt paving."

While county-based environmentalists have taken a hard stance against Caltrans, the Save-The-Redwoods League -- the first group to fight for the preservation of the great trees -- has thus far taken a nuanced view. On March 29, Executive Director Ruskin Hartley acknowledged that the League has "a long and difficult history of working with Caltrans going back to the ’30s," citing work on the Avenue of the Giants, Prairie Creek and Cushing Creek as examples of projects where hundreds of old-growth trees were cut. But representatives "who took a look at the draft and walked the alignment with Caltrans" were encouraged by the fact that no old-growth redwoods will be removed, and struck by the fact that several in the main project area are scarred from being hit. "From a human safety perspective, and the health and safety of the trees, it's not an optimal situation," Hartley said.

The League does share others' concerns about how roots will be impacted. "The last frontier in the redwoods is what happens in the ground," Hartley continued, "and yet there are cases where the trees right next to the road have remained healthy." In regards to an oft-discussed section on the Avenue of the Giants "where all the tops have died back," Hartley theorized -- as others have -- that "the placement of culverts and ditches seem to have really affected the hydrology. As long as the water supply is left intact, the trees seem to do okay." So does the League support or oppose the project? "It's hard to have a definitive point of view without having seen the final EIR," Hartley responded. "But Caltrans does keep raising the bar on projects like this. They have managed to find a way to do it without cutting big trees."

Project opponents have also criticized Caltrans for failing to invest in a full EIR from the get-go; instead, the agency had to be pressured into doing so, after receiving correspondence from numerous groups including the Northcoast Environmental Center and EPIC. Caltrans has also come under fire for initially refusing to conduct a marbled-murrelet count in the area, on the grounds that -- per a Jan. 15, 2009, letter from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service -- "no murrelet nest area or habitat would be disturbed by the proposed project." The agency has reversed that decision because of pressure from environmental groups, and now plans to conduct a survey this spring at an estimated cost of $300,000.

The Big-Box Argument

Project opponents also argue that opening 101 to STAA access will open the floodgates for big-box development in Humboldt County. Describing the "buffer zone" that isolates the North Coast, "You can see why Wal-Mart and Home Depot are asking for STAA access," Dr. Ken Miller said at EPIC's Feb. 24 forum in Garberville. "They're asking for it in the Del Norte County Goods Movement Plan. You wouldn't know that if you listen to our county and Caltrans; they don't tell you that."

No discussion of the Richardson Grove proposal ever ends without the specter of Home Depot being invoked at least once. Among opponents, there is a widespread belief that the sole purpose of the project is to facilitate the highly controversial Marina Center project. In other words, it's all being done for Marina Center developer Rob Arkley. "It is worth noting that we have already witnessed the reliance on an STAA designation, as revealed in the Marina Center Project DEIR, which specifically refers to using STAA trucks," EPIC wrote on March 24. "So the concern about an STAA designation opening up the area to big-box stores is not speculation."

But according to Randy Gans, Vice President of Real Estate for Arkley's Security National Corp., "When the Marina Center was designed, the parking lot and the intersection were designed for STAA access per the request of Caltrans." And while it's "absolutely" true that there are still plans to anchor the complex with a Home Depot, "in no way, shape or form has the relevance of STAA ever come up in our negotiations with that store," Gans told the Journal on March 8. "They're serving a Home Depot and a Wal-Mart in Crescent City without STAA access. ... If anything, it puts the local retailers at a disadvantage, because they don't have the resources that Winco and other big-box stores have."

Gans added that for its part, Security National "has never once lobbied" for STAA access, and has not submitted comment to Caltrans about the Richardson Grove proposal. He further opined that big-box stores will only come to Humboldt County if they perceive that it's economically sound to do so: "Home Depot is interested in this market because there's a demand for it here," he said. "There are a lot of goods sold by Home Depot to Humboldt County residents, but those goods are sold outside of the county and those dollars are spent elsewhere [in Crescent City, for example]."

In response to a question about corporate stores that are already here, EPIC's reply was, "Your mention of existing big-box stores with their own fleets of trucks establishes that the STAA designation is not necessary." But not necessary for whom? If the big boxes don't need STAA access to be here, how can providing that access be the cause of their coming here? The argument seems to be circular and self-defeating. It is, of course, "necessary" for Caltrans to be in compliance with federal law -- a fact that was curiously ignored at the Feb. 24 forum.

Several people interviewed for this story questioned the idea that a corridor open to STAA traffic would quickly become overrun with commercial trucks, or that Eureka will become another Santa Rosa. "The only time I can think of where someone on I-5 would choose 101 is if there's snow in the Siskiyous, and the road is closed," Second District Supervisor Clif Clendenen said on March 18. "Even then, they'd probably just be advised to sit tight and wait. ... I don't believe it to be true that truckers will use this as a conduit."

"If the road access was going to turn us into a hotbed of economic activity, Redding would be becoming one now," Bob McCall, Sales & Marketing Manager for Cypress Grove, said on March 5. "They've got cheap land, cheap housing, and access to I-5 -- but their unemployment rate is higher than ours." J. Warren Hockaday, President/CEO of the Eureka Chamber of Commerce, emphasized the differences between Santa Rosa and Humboldt County: "Santa Rosa was a bedroom community to the Bay Area, and housing was affordable there," he told the Journal on March 9. "The development was driven more by investment than community interest. It was a different time, with different circumstances and different politics. I can't imagine it happening here."

Caltrans has been soundly criticized for failing to provide a more in-depth analysis of the economic justifications for the proposal in the DEIR. According to Floyd, "the final EIR does have sections on land use, community impacts and growth. I have heard many concerns about big box and why the project is planned. ... Humboldt County Planning conducted a business survey, and from that survey we performed an analysis. This was limited only to those sectors responding to the survey, and within those sectors, the response rate was significant. Those responding were likely the businesses most concerned with shipping costs."

County officials -- including Clendenen, First District Supervisor Jimmy Smith, Fourth District Supervisor Bonnie Neely, and Economic Development Director Jacqueline Debets -- were all of the same mind when it comes to keeping Humboldt County rural. "I share the fear of big-box development, but this isn't what's going to stop it," Debets said on March 10. "It's a red herring." "I don't believe living in self-imposed transportation isolation is the way to limit big-box development," Neely wrote in a March 17 e-mail. "Each community needs policies in their General Plan. In Humboldt County, our Board established discretionary review authority over any big-box development, meaning we can review and decide to approve or disapprove each proposal on a case-by-case basis. This is the process for weighing the impacts of big boxes on our local businesses and environment."

Is a Fight For the Grove Near?

The opposition campaign spearheaded by EPIC has certainly been fruitful: During the official public-comment period, which ended on March 9, 2009, Caltrans received about 1,000 comments, approximately 300 of which were form letters. The agency is mandated to provide official responses to all comments received in that period. By comparison, about 300 comments were received on the Environmental Impact Statement for work on the Eureka/Arcata corridor, another controversial project.

That's not all. According to Dyer, since the official public-comment period was closed, "we have sent in over 2,000 postcards from concerned community members to Caltrans, opposing the project and supporting our campaign. Now we are teaming up with the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council, the Bay Area Coalition for the Headwaters, the Center for Biological Diversity, and others in a new coalition opposed to this project. This organizational collaboration is in addition to our ongoing participation in the Coalition to Save Richardson Grove locally."

Meanwhile, it appears that EPIC is preparing to go to court. "Fundamentally, the DEIR was a legally deficient document, and absent a new document which is circulated for public review, we think it violates the law," EPIC wrote on March 24. Duggan would not confirm that they're preparing a lawsuit -- "We really cannot discuss potential legal claims in hypothetical situations" -- but the indicators are clear that they are. It's now up to Caltrans to consider whether there are any more environmental mitigations it can make, and to bolster its economic argument.

In next week's issue, the impact of transportation costs on local businesses will be examined, along with weaknesses in the arguments set forth by both Caltrans and its opponents.

Cristina Bauss is a staff writer for The Independent and a reporter for KMUD News.

Comments (39)

Showing 1-25 of 39

more from the author

-

Pity and Fury

In Southern Humboldt, a painful reckoning with the inevitable

- Oct 12, 2017

-

Roads and Redwoods

Inside the big fight over the Richardson Grove project: Part II of II

- Apr 15, 2010

-

Drive-Thru Redwoods

No peace in SoHum over Richardson Grove realign

- Jan 8, 2009

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023