Reinventing Scotia

The "last company town" will soon gain its independence, for better or for worse

By Ryan Burns [email protected] @RyanBurnsy[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

In the middle of the storybook lumber town of Scotia, right at the elbow of Main Street between the stately Scotia Inn and a row of quaint bunkhouses, there's a building that looks like a Lincoln Log replica of the Lincoln Memorial. The Scotia Museum, with its robust columns, gable roof and decorative pediment, is textbook Greek Revival architecture, a style that was already on its way out when the Pacific Lumber Company constructed the building as the town bank in 1920. But it's easy to see why they chose the style anyway: Old growth redwood trees make great columns. Their trunks are perfectly cylindrical, and the grooves in their fuzzy bark look a lot like the flutes and fillets carved into Grecian stone. Up close, the all-old growth building has the rich scent of damp soil.

On the manicured lawn just south of the museum sit an old train engine and a steam donkey, long-retired relics of the Industrial Revolution. A slice of old growth redwood, eight or 10 feet across, stands upright on a brick pedestal, its once-rosy heartwood turned ashy with age and cracked through the middle like the Liberty Bell. At the base of this humongous wheel, mounted on a hunk of granite, a metal plaque tells the story of the Pacific Lumber Company, which birthed the town whole some 150 years ago. "Scotia is one of the last company-owned towns," the plaque reads. "With a population of 1,200, almost everyone works for the Pacific Lumber Co. ... Humboldt County's largest private employer, providing jobs for nearly 1,600 people."

The sign was installed by The Native Sons of the Golden West on Valentine's Day, 1998. Less than 12 years ago, and yet its story is as outdated as the nearby machinery. It's hard to imagine any of Scotia's current residents, none of whom work for PL, which was dismantled in bankruptcy proceedings three years ago, reading this sign without a touch of bitterness. The final sentence offers a paternalistic promise: that the company is "dedicated to preserving a heritage, producing high quality redwood and Douglas fir lumber products and continuing that tradition for the future."

Realistically, the illusion of perpetual rewards had already begun to crumble by 1998. Thirteen years earlier, Houston financier Charles Hurwitz, whose name would become an epithet in Humboldt County, gained control of PL via hostile takeover, selling hundreds of millions of dollars in junk bonds to acquire a majority share of the company's common stock. To finance this massive debt, Hurwitz liquidated valuable company assets and abandoned the sustainable harvesting practices that had been the company's trademark through three generations of management by the local Murphy family. Under Hurwitz's Maxxam Group, PL more than doubled harvest rates, felled countless 1,000-year-old trees and by 1998 had accumulated enough Forest Practice Rules violations -- 126 of them in 1997 alone -- to become the first and only company in California history to have its timber operator's license revoked.

Ultimately, no amount of clear-cutting could cover the massive debt, and in 2007 the Pacific Lumber Company filed for bankruptcy. In the ensuing reorganization, Mendocino Redwood Company, a major PL creditor, took ownership of the sawmill and most of the timberland (and renamed the operation Humboldt Redwood Company) while the town of Scotia, including the historic inn, hospital and theater, the shopping center and all 270 homes, went to another creditor, Marathon Structured Finance Fund, under the name Town of Scotia Company, LLC. The company town became a town company, so to speak.

The arrangement is temporary. Two weeks ago, the county Board of Supervisors approved a General Plan amendment and rezoning request, initiated by PL in 2005, that paves the way for Scotia residents to be allowed to purchase their own homes. The inn will soon be sold to a hotelier, the power plant to a power company, the shopping center to a commercial investor and so on. TOS administrators say they're giving the town its independence so that residents can finally realize the American Dream of homeownership. But many residents feel Scotia's glory days are in the past, not the future. Under the wing of company ownership, Scotians have largely been spared societal headaches like unemployment, infrastructure management and crime.

The town looks more or less like it did 100 years ago, and nostalgia runs thicker here than perhaps anywhere else on the West Coast. But, like it or not, the era of company towns is over. At a cost of more than a million dollars per year, managing the town is simply not economically feasible for Marathon or any other company. The only question now is how independence will affect on Scotia. Will it allow residents to reclaim the pride and sense of purpose lost under Maxxam, or will opening the doors to modernity erase the things that give this place its unique charm?

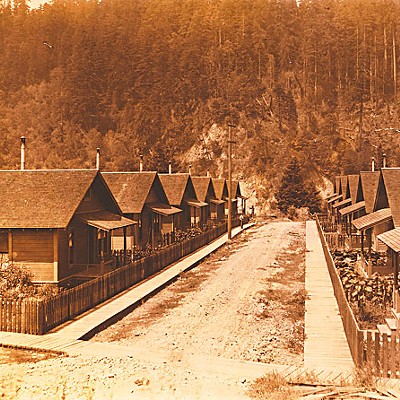

Scotia's K-through-eighth school -- 216 total students -- sits atop a hill, its cyclone-fenced playground overlooking a repeating pattern of rooflines formed by the nearly identical bungalows laid out below in tidy rows. The homes are painted in a limited range of hues, per PL policy, and the town's clean, narrow streets have the insular feel of a movie studio backlot. "Scotia," said the New York Times in 2006, "is both immaculate and surreal, equal parts Mayberry and Twin Peaks." Towering beyond the houses, on the bank of the Eel River, the hulking metal machinery of a power plant -- all chimneys, pipes and scaffolding -- emits thick, billowing plumes of steam. Redwoods and Douglas fir blanket the hills in all directions.

Local resident Robert Rexford walks through the school's damp parking lot to pick up his son from kindergarten. "I liked it when it was Pacific Lumber," he says, and it's not clear whether he means the mill, the town or both. He was employed by PL for 21 years, then spent a year working at the Evergreen Pulp Mill before it, too, went belly up. He's currently unemployed. Previously, all Scotia residents had to be PL employees. "Now anybody can move in," Rexford says somewhat bitterly. "It's not like it used to be, for sure." Asked if he plans to continue living here, he replies, "Until they start selling off the homes." Attitudes in town are split, he says. "A lot of people want to buy their homes. Some can't."

Approximately 800 residents live in the town's 270 homes. Just 60 of them work at the mill. Occupancy remains full (there's even a waiting list) thanks to the likes of police officers, forest rangers, teachers and students who commute elsewhere each day. In this age of freeways, CostCo and the Internet, the company town is an anachronism. Or rather, it was.

"This is the last one anywhere," asserted TOS Vice President and Director of Legal Affairs Frank Bacik. "We know of no other towns like this." Last of its kind or not, Scotia isn't ready to join the 21st century just yet. The rezoning recently approved by the county will simply reflect the town as it currently exists. Its two existing parcels, zoned industrial and unclassified, will be subdivided into smaller lots and rezoned according to what's already there -- just paperwork and line drawing, really. But serious work is needed beneath Scotia's pristine surface.

"This is a 150-year-old town that was owned by entity that didn't have to say 'please' or 'may I?' when they put in a power or water line," Bacik explained. "These things were jerry-rigged over a period of time. Water mains go under people's houses. Sewer lines go between houses, take a left turn under a porch and go across the street." TOS plans include a phased development to relocate sewer and water lines to new trenches following street rights-of-way. The streets themselves must be rebuilt to reflect current Department of Public Works standards (or a scaled-down version, at least), including new curbs, gutters and asphalt, driveway aprons and ADA-compliant ramps.

Bureaucratic hurdles also remain. The Local Agency Formation Commission, or LAFCo, must approve a proposal to transfer management of the town's infrastructure, recreation facilities and volunteer fire department from TOS to an elected community services district board. And the California Department of Real Estate will require disclosures on water quality, sewage handling and infrastructure financing. Bacik said the entire project, which proposes no new development or changes in current usage, will take five to seven years. But he anticipates homes will start hitting the market in six to 18 months.

Current residents of Scotia will get first crack at purchasing them (their leases provide the right of first refusal), but ultimately the houses will be available to anybody and priced according to what the market will bear. "They'll be affordable or we're not doing our job," Bacik promised. "These are small homes in a dense urban atmosphere near a power plant and a sawmill."

In approving Scotia project proposal, the Board of Supervisors characterized Scotia a bit more charitably. Supervisor Clif Clendenen, who was born in the Scotia hospital in 1953, noted the value of the town's historical character and community pride. He and Supervisor Mark Lovelace held Scotia up as a shining example of new urbanism and high-density planned development -- hot-button concepts during the county's ongoing General Plan update.

"This is a perfect example of all of these things," Lovelace said, "and it's wonderful."

The town of Rio Dell, just across the bridge from Scotia, provides an interesting compare-and-contrast for the old lumber town. Javan Saffell was born in Scotia, and in third grade his family moved across the Eel to Rio Dell. Outside Hoby's Market and Deli in Scotia on a recent afternoon, Saffell said both towns have a friendly atmosphere but that Scotia, unlike Rio Dell, has remained unchanged over the years, despite several floods and a 1992 earthquake that caused a fire, which burned down the shopping center.

"Rio Dell's a small town but feels like a ... ." He paused, looking for the right words before giving up and addressing Scotia instead: "This is a beautiful town that's kept up." In part by Saffell's own father. "My dad still works for PALCO," he said. Then, realizing his mistake, he corrected himself. "For Scotia. He's the gardener."

While PL provided Scotia with plumbing, carpentry and gardening crews, Rio Dell has been more visibly affected by the drastic downturn in the lumber industry. Their property values, household income and education levels rank well below the state average, and the town's crime rate is much higher than Scotia's. A previous plan would have annexed Scotia to Rio Dell, but Scotia's owners balked at a request for expensive infrastructure upgrades, and its residents expressed a desire for independence.

Scotia's home inventory will help the county achieve state-mandated affordable housing supply quotas, but many people worry that, in the absence of a thriving industrial base, the historical character praised by Clendenen will begin to deteriorate. The town has already begun to transition into a bedroom community, which tend to function better in higher-income areas.

"Often times it's more difficult for poorer people to live in a bedroom community," said Humboldt State University Associate Professor of Economics Beth Wilson. Without a reliable automobile or convenient alternative (the bus comes to Scotia, but it takes more than an hour to reach Eureka), people like to live close to their jobs, Wilson said. "What might be more common to see," she speculated, "is wealthier people might come in, buy a couple of lots next to each other, tear down the [existing] homes and build something larger. Gentrification."

Such development would require its own series of community and governmental approvals, but it's not out of question. Another possibility is that outsiders will purchase many of the homes and maintain them as rentals. Better than either of these options, Wilson said, would be to bring jobs to Scotia. County-wide, niche manufacturing has helped fill the void left by the loss of timber and fishing jobs, Wilson said, and a small town like Scotia could benefit from, say, an industrial park.

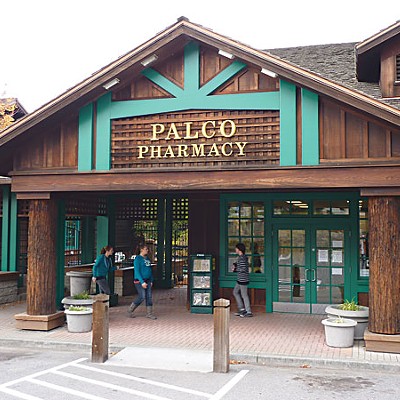

Bacik said things have already been moving in that direction, with a wide variety of companies submitting proposals to locate inside Mill A, the massive structure that used to house the saws and handling equipment for giant old growth redwoods. Now mostly empty, with broken window panes and peeling paint, the building has been converted to the Scotia Industrial Park, home to the Eel River Brewery, a sheet metal manufacturing shop and a mobile truck servicing company.

Bacik said he recently wrote a lease for an indoor archery facility and is in talks with a group that acquired an in-line hockey rink from Southern California, complete with the perimeter boards, Plexiglas and scoreboards. "We have the only building in Humboldt County big enough to hold it without a post holding up the roof," Bacik said. In addition to hockey, he said it could host indoor soccer, basketball, volleyball and even roller derby. He also mentioned a Native American casino, hotel and RV park called "The Mill" that's located in an old Coos Bay, Ore., lumber mill.

"The possibilities seem endless," Bacik said.

Inside the Scotia Museum and various other buildings around town you'll find old sepia-tone photos of men with handlebar mustaches sitting astride felled redwoods as thick as school buses, or pushing through the Scotia log pond on a de-barked redwoods like lumberjack gondoliers. Mounted on walls you'll see old whipsaws, circular saws and rope-thick cables, ink-dotted paperwork and countless old stories. But it's not just the wall hangings; the entire town is something of a museum, a curious relic of the past, well preserved if obsolete. Like any museum, Scotia's artifacts -- the inn, the homes, the mill ... all of it, really -- juxtapose the past with the present. People who've been here for generations can and quite often do recount old stories -- taking their future spouse to the Winema Theatre, playing baseball at the old ballpark or roller-skating at the rink before it was destroyed in the ’55 flood. As Scotia belatedly enters the 21st century, some of these old-timers are waxing a bit wistful at the inevitability of change.

The Bertain family moved to Scotia in 1920. Bill, the youngest of 10 children, fondly remembers his days attending Scotia Elementary School (even after his family moved to Rio Dell).

"[Scotia] was a wonderful place to live then," Bertain said. "It felt like I lived in the Golden Age."

Bill Hunsaker worked for PL from 1937 to 1984, just prior to Hurwitz's takeover. When he moved into Scotia just after World War II, rent on the four-room house he shared with his wife and two children was $42 per month. Garbage and water service was free, and free firewood was delivered weekly. The company, he said, always treated him well.

"It was the best you can imagine," said Hunsaker, now 90. "When I first started to work there I was a mail boy, and when I retired I was a vice president. So I guess you can't complain about that."

The days of 47-year careers with the same company are pretty much gone in Humboldt County. Humboldt Redwood Company, which resurrected sustainable harvesting practices, has been forced to lay off workers and drastically reduce harvesting during the current housing slump, the worst in decades. Current Scotia residents have very little job security, to say nothing of the next generation.

On a recent brisk, foggy day, just after the mill's lunch whistle blew, rows of kids started filing down the hill from the school to Hoby's Market, where they gathered, laughing and chattering, around the deli counter. Outside, three eighth-grade boys talked about the good and the bad of living here.

"It's OK," said one who's lived here his whole life. "They need to put some more activities for kids in, like skate parks. And they should put, like, more restaurants in and stuff."

His friends agreed. Asked what their parents do, another boy replied, "My dad doesn't work for the mill anymore because everybody started getting fired."

"My dad got laid off too," said the third.

What do they do now?

"My dad does construction," said the first.

"My dad works down at South Fork School," said his friend.

The third looked sheepish for a second, then, shrugging it off with a laugh, said, "I have no idea what my dad does."

Which says something about Scotia at the end of 2009: The singular identity that defined this town for the past 150 years has been relegated to plaques and old photos. The present is complicated and difficult to track. And the future, well, Frank Bacik got it right: The possibilities -- good, bad or somewhere in between -- are endless.

Comments (10)

Showing 1-10 of 10

more from the author

-

Last Days of the Surfing DA

Heading into his final year in office, Paul Gallegos talks politics, family and The Smiths

- Jan 2, 2014

-

Unequal Opportunities

Behind the ACLU's allegations of racial, sexual and disability discrimination in local schools

- Jan 2, 2014

-

Systematically Misled

- Dec 26, 2013

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023