[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

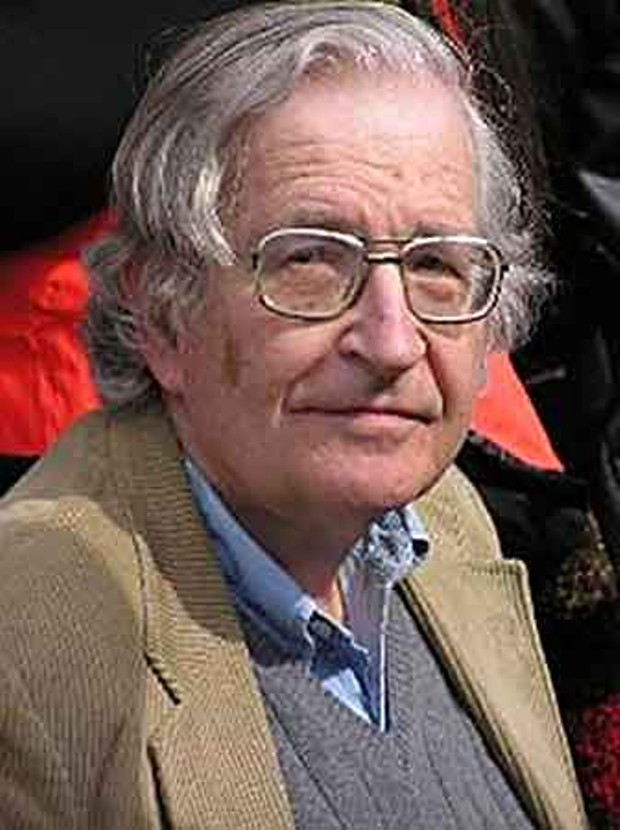

He is the Copernicus of language studies, and by extension, of much of what goes on in the human brain. Until Noam Chomsky (now 80) came along in the late 1950s, linguistics mostly consisted of cataloging and comparing languages from remote parts of the world, attempting to discover family trees and perhaps -- in the most optimistic of scenarios -- recovering a hypothetical original language. For Chomsky, what really mattered about language wasn't that it came from a particular district in Java or the west coast of Greenland or Orick; what mattered was that it came from the depths of the human mind. Instead of searching for a mythical "Ur" language, many linguists and neurologists have spent the last 50 years trying to understand how something as complicated as language -- any language -- can be learned effortlessly by virtually all young children.

Like any scientific theory, a theory of language should explain as much as possible with as little as possible. Copernicus, for instance, proposed that cumbersome earth-centered theories of planetary motion could be discarded in favor of an elegant sun-centered system. Darwin's three-step "heredity-variation-selection" theory of evolution simplified, well, just about everything. For his part, Chomsky looked beyond the complicated sentence structures we humans regularly use (in English, "The man bit the dog" and "The dog was bitten by the man"). He proposed instead simple "deep structures" that we unconsciously transform into our daily utterances, including such hard-to-parse speech as "um" and "er," the different ways we pronounce "ketchup" and our use of intonation.

The problem that Chomsky addressed head-on was what's been called the "poverty of stimulus" phenomenon: How can a three-year old child utter novel sentences based on his or her limited exposure to language? You can be fairly sure that a young kid never heard the exact sentence, "Why does the cat like the green bowl more than the brown one?" -- try getting a computer to say that! -- but out it comes, usually in what we think of as perfect English. Chomsky's solution -- one that has been embraced, challenged, refined, mutilated, discarded and reinvented over the last few decades -- was that all of us are born with a mental component (sometimes called the Language Acquisition Device) that incorporates a Universal Grammar. With the right stimulus -- that is, spending 30-odd months listening to one the 6,000 languages now spoken -- the child's innate language ability kicks in and speech emerges in an almost magical way.

I've barely scratched the surface of Chomsky's influence on linguistics here (and haven't even touched his radical-left politics), but if your curiosity is aroused, I recommend Steven Pinker's The Language Instinct or Christine Kenneally's The First Word. Be warned: once you're bitten by the linguistic bug, it'll never let go.

Barry Evans has no regrets, other than going into engineering when he could have studied linguistics. He lives in Old Town Eureka.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Eclipse!

- Mar 28, 2024

-

The Little Drone that Could

- Mar 14, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022