|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | STAGE

MATTERS | OFF

THE PAVEMENT

BOOKNOTES | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

November 23, 2006

Food: the tie that binds

by JUDY

HODGSON

"What is it with this

family? How come all our gatherings, every time we get together,

it's all about food? We are obsessed. It's all we talk about!

When we finish one meal, we're planning the next. Even our vacations

are all about food!"

That

statement was shrieked in my direction once, years ago, by one

of our grown daughters, who shall remain nameless because ...

well, she was on a diet and none too happy about it. And she

was exaggerating. But just a little. That

statement was shrieked in my direction once, years ago, by one

of our grown daughters, who shall remain nameless because ...

well, she was on a diet and none too happy about it. And she

was exaggerating. But just a little.

Then, one night last week, my husband said "Remember

that Utah trip we took? What's-her-name, our niece ... that soup

she made after skiing?"

That Utah trip was in the late '80s or early '90s,

at least 15 years ago, and I knew exactly the soup he was talking

about tortilla soup with an entire bar loaded with toppings ready

to pile into our steaming bowls. Shredded chicken, cilantro,

homemade crispy tortillas and lime wedges to squeeze on top.

It was fantastic. And her name is Jennifer, I reminded him, not

for the first time. Spain? We remember that trip because of the

fried calamari sandwiches and olives in the tapas bars. Mexico?

Shrimp, margaritas and piles of guacamole. We eat guacamole every

day we're there because the buttery perfect Haas avocadoes are

about 10 cents apiece.

Left and below: A trip to the former Soviet

Union in the early spring of 1988 was a grim food experience

until the tour group traveled south to Kiev in the Ukraine. The

open markets there were bountiful with fresh meat, dried nuts,

dates, plump apricots and babunyas (grandmothers) offering dried

mushrooms on a string.

I am writing this before Thanksgiving and no, I'm

not going to give you my family recipe for turkey tetrazzini.

But I did want to write about families, and family gatherings,

and, well ... food.

Like the music we listen to and the books we read,

food is such a strong part of our culture. It's who we are. I

was raised in Los Angeles in the '50s by my mother, the daughter

of Russian immigrants. My father died when I was young and we

had no nearby family on that branch of the tree. So my brothers,

sisters and I had my mother and her mother my babunya, the one

who taught me when you are cutting vegetables for borscht all

the little pieces had to be the same size because if they were

irregular or big, you were a sloppy cook. Except the potatoes,

which as everyone knows are peeled and cooked whole in the broth,

removed, mashed and then added back to thicken the borscht.

Shashlik (lemon-onion marinated lamb kebobs)

and vareniki (dumplings filled with egg and hoop cheese)

are part of my food DNA. But I'm also an L.A. kid, so I love

chorizo and scrambled eggs for breakfast, and what all in our

family affectionately call McGirk Street tacos, made by my mother

who often sent me to the corner store to buy fresh corn tortillas,

still warm and sold by the kilo.

I

was prompted to write this family/food story by an article I

read recently by Anne Raver first published in the New York

Times and then last Saturday in the San Francisco Chronicle.

She wrote about how she had hired a live-in caretaker for her

93-year-old mother who still insisted on living alone. The caretaker

assumed many of the duties this feisty woman had previously done

for herself, like making her own morning coffee and other cooking

chores. Eventually, Raver wrote, her mother "lost her joie

de vivre. She spoke in a whisper when I came by to chat,

and she didn't have much to say. `Everything is fine,' she said

with a thin smile." Long story short, the aide eventually

left and her mother perked right up, resuming her own cooking

chores and regaining her independence with all the enthusiasm

of a 16-year-old who just passed her driver's test. I

was prompted to write this family/food story by an article I

read recently by Anne Raver first published in the New York

Times and then last Saturday in the San Francisco Chronicle.

She wrote about how she had hired a live-in caretaker for her

93-year-old mother who still insisted on living alone. The caretaker

assumed many of the duties this feisty woman had previously done

for herself, like making her own morning coffee and other cooking

chores. Eventually, Raver wrote, her mother "lost her joie

de vivre. She spoke in a whisper when I came by to chat,

and she didn't have much to say. `Everything is fine,' she said

with a thin smile." Long story short, the aide eventually

left and her mother perked right up, resuming her own cooking

chores and regaining her independence with all the enthusiasm

of a 16-year-old who just passed her driver's test.

I knew exactly what Raver was talking about. In

2000, my own mother moved from her home in Big Bear (in the mountains

east of Los Angeles) to live with my husband and me in Fieldbrook.

At the time she was recovering from heart surgery and pretty

run down, but eventually she bounced back. The three of us became

good roommates and all shared cooking duties. My mother took

over all the shopping chores and you would often see her tooling

around town in her little red Nissan. She would wander the Co-op

aisles for hours "because they sell so many interesting

things." After four years, however, she bought herself a

little mobile home in McKinleyville and moved out, cheerfully

telling everyone she was divorcing us. She missed her independence.

As long as she was healthy enough, she wanted to be on her own

like she was for the previous 18 years, ever since she lost my

stepdad.

One of those independent things she missed was

cooking all her own meals yes, three times day and eating exactly

what she wanted when she wanted it. She always ate dinner at

6 p.m., not 8 p.m., as we preferred. When my husband cooks, he

doesn't particularly care if you think something is weird, or

if you like it. The important thing is he likes it. For instance,

he makes a smoky, grilled radicchio salad sprinkled with corn

kernels and straight radicchio that's not exactly for everyone's

palate. My mother, however, tended to choose food to please  others,

her roomies, when it was her turn to cook. I noticed that when

she was back on her own turf, however, out came a lot of the

old recipes. She made akroshka, a cold buttermilk, cucumber

and egg soup. Or stewed tomatoes, not a big favorite of mine.

Some nights she just ate leftover lima bean casserole if she

felt like it. And she made borscht again, happily sharing it

with neighbors since it's impossible to make a small quantity

of borscht. others,

her roomies, when it was her turn to cook. I noticed that when

she was back on her own turf, however, out came a lot of the

old recipes. She made akroshka, a cold buttermilk, cucumber

and egg soup. Or stewed tomatoes, not a big favorite of mine.

Some nights she just ate leftover lima bean casserole if she

felt like it. And she made borscht again, happily sharing it

with neighbors since it's impossible to make a small quantity

of borscht.

Left: The author's mother, Holly Gubrud, spoke

fluent Russian to students in St. Petersburg, eager to learn

of news from outside the Soviet Union. the building in the background

is the Hermitage.

I would often stop by on my way to work and she

would offer me coffee perked in her old aluminum pot or some

tea. On my way home, we often shared a glass of wine and nibbled

on pistachios, Brio bread and olive oil, a daily habit she acquired

when she lived with us. I would sit and watch her cook her early

dinner and we would talk about family history past and present,

trips we'd taken together and yes, food.

In 1988, the two of us took a journey of a lifetime

together to Russia (then the Soviet Union). Since she did not

speak English until she went to kindergarten in Los Angeles,

her language skills quickly returned and she was my interpreter.

It allowed us incredible freedom to go anywhere and mingle with

ordinary people. Instead of the hotel dining rooms frequented

by our American tour partners, we ate where the Russians ate,

often in cafeterias. The food was mostly grim and not the Russian

food of my childhood. As we traveled from St. Petersburg to Novgorod

to Moscow, we noticed there was one cheese a rubbery tasteless

white blob in the entire country. It was very early spring, so

there were no fresh vegetables or fruit. Cafeteria, by the way,

was a misnomer. There was often no choice involved. At one place

we ate steaming bowls of broth with dumplings the only selection.

We were going to have tea, but at the end of the line I saw something

from my childhood and busted out laughing. It was prune juice.

Not the stuff we find in a bottle at Safeway. My family made

prune juice from dried prunes boiled in sugar water and lemon.

It was served with a plump prune in the bottom of the glass.

Wherever we traveled, we shared tables with people, told our

stories and listened to theirs.

The food improved as we traveled south to Kiev,

where they told us they were not Russians, they were Ukraines,

and they certainly knew how to eat. At the open markets, we feasted

on nuts and dried apricots and watched the butchers practice

their art. (My mother, several uncles and cousins were all butchers

in L.A.) We were supposed to travel south all the way to Yerevan

(in the Caucasus Mountains) where my family originally came from,

but that leg of the trip was canceled due to civil unrest. I'm

sure the food there would have been even better.

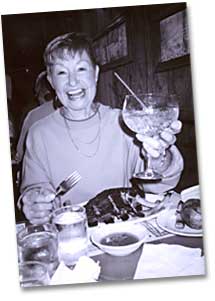

Last Thanksgiving, my mother (pictured at right)

was briefly in the hospital and then, with the help of Hospice

(a story for another day), I took her home to McKinleyville.

She died Dec. 15 at age 85. So in her honor, here's one of her

recipes when you get tired of leftover turkey. My No. 2 son-in-law

Phil, who loves peasant food, thinks I'm a genius when I cook

it.

Cut the core out of a head of cabbage, put the

head in a deep bowl and pour boiling water over it to wilt the

leaves. Mix a stuffing of ground lamb, finely chopped onions,

salt, pepper, lots of dill weed and a handful of uncooked rice.

(Russians don't measure.) Cut the tough rib end from each cabbage

leaf so they will roll easily. And here's the secret: put a pitted

prune in the center of each meat roll. Place the rolls in a deep,

heavy pot, cover with water and canned tomatoes. Top with quartered

carrots and potatoes and any leftover cabbage, more salt, pepper

and dill, and simmer on a low flame, slowly for a very long time,

at least an hour. Top the rolls with sour cream, a staple in

every Russian's refrigerator.

Even my grandchildren will eat these cabbage rolls

(except the one who sneakily peels off the cabbage and pushes

it to the side of his plate). I just tell them there's a secret

inside each roll. It was a family secret, now it's yours.

your

Talk of the Table comments, recipes and ideas to Bob Doran.

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | STAGE

MATTERS | OFF

THE PAVEMENT

BOOKNOTES | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a

letter!

© Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|