|

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER September 29, 2005

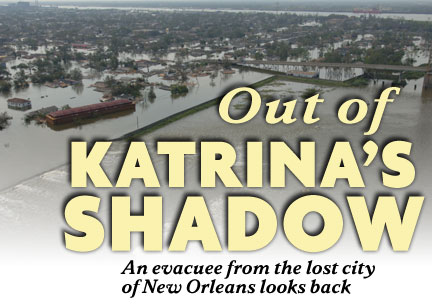

Above: A hurricane-damaged

New Orleans levee, one day after Katrina. Photo by Jocelyn Augustino/FEMA. by REBECCA BIDWELL-HANSON I don't want to get out of bed just yet. I don't want to see what really happened yesterday. My husband's already been up for a while, though. I've been listening to him talk to our dog and watch the news, but I can't hear what's being said, exactly. As I walk toward the armchair in our Baton Rouge hotel room, Paul's face, always calm and gentle to me, has an unsettling shadow this morning. He tells me that Hurricane Katrina wasn't the direct hit New Orleans was expecting, but that we're not out of the woods yet.

Right: Rebecca Bidwell-Hanson. Photo by Bob Doran. These images eat away at me, little by little. I imagine the students of the Lower 9 Head Start whom I'd worked with through my early childhood program at the Audubon Zoo, and the four teachers from that center who became my friends during a summer professional development program. I study the screen for their faces, but I can't find them. Across the city, Lake Pontchartrain fills the Lake View area. Water rushes over the 200-foot break in the levee near the 17th Street Canal, slapping against the roofs of the large, affluent homes there. The manicured lawns lurk below two or more stories of water. I try to absorb shot after shot of New Orleans under water, New Orleans thrashed and battered, New Orleans with trees, debris and the remains of homes and businesses scattered and washing away in the flood. I imagine bodies of people and animals floating among the rubbish and think it's only a matter of time before we see that on TV, too. Besides that, the only thing I haven't seen so far is a spot of dry land. And then there's more bad news. Another newscaster explains that water from the lake is still pouring into the city. Water levels all around New Orleans are rising. Waves flow down Canal Street. Now he announces that a 50-inch water main break has contaminated the city's drinking water. Nothing can be done to repair the break or restore the power until the floodwaters have been drained. New Orleans will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.

Left: Aerial view

of New Orleans the day after the hurricane hit.

Sometimes I think that it couldn't have been that long ago since my husband and I sat in our friends' living room having drinks and joking about another evacuation. "Don't they know this is the beginning of the semester, and I've got an NIH grant to worry about? I just don't have time for this right now," I mocked Bruce, one of Paul's colleagues, using his argument against evacuating for Tropical Storm Cindy in July. We all laughed. When I first moved to New Orleans over three years ago, such conversations would have shocked me, but in the midst of my fourth hurricane season I started to see things differently. Every year the tropical storms and hurricanes trail in one by one, so that Gulf Coast residents would have to move out for most of the summer and fall if they evacuated every time one popped up in the Atlantic. While staying to ride out these storms was a gamble, leaving for a storm that never materialized was a gamble as well. Lost wages and looting were just a few of the risk factors involved with leaving. When I worked as a public school teacher and then as an education coordinator at the Audubon Zoo, I even felt a certain amount of peer pressure from co-workers each time a storm was predicted to roll in. As a New Orleans newcomer, I often bowed to my more storm-experienced colleagues' assessments of oncoming storms. Luckily, not all of them shared the native New Orleanian attitude depicted on the local news every hurricane season. Without fail, someone would be pictured saying, "I'd rather die in New Orleans than live anywhere else," or some such nonsense. But they weren't joking. And we knew it wasn't a joke when we got home around 7:30 p.m. on the evening of Friday, Aug. 26, and turned on the television. A special broadcast featured a collection of parish presidents and local mayors (not including New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin), as well as local emergency officials. They were warning that Hurricane Katrina was heading our way, with the latest projections showing a direct hit on the city of New Orleans. As Katrina lingered over the Gulf of Mexico, gaining force by the minute, meteorologists predicted she would register a Category 4 by the time she made landfall. "If it's a direct hit, New Orleans could be wiped out," I said. "I think we should get out."

When I woke up on Saturday morning, Paul was already sitting on the futon holding a mug of coffee. While residents of St. Bernard, Plaquemines and Jefferson parishes had already begun to evacuate, Mayor Nagin told the people of New Orleans that neither a mandatory nor voluntary evacuation was being called. In the next breath, he encouraged those who had the means and the will to get out to do so a soon as possible. Paul had already booked a room at the AmeriSuites Hotel in Baton Rouge, one of the few that would allow us to bring Molly, our 6-month-old lab mix. We decided that Paul would go

to the grocery store to buy bottled water for the drive, in case

we ended up sitting in traffic for hours, as many people did

during the evacuation for Hurricane Ivan last year. I would start

packing. I walked to the closet and pulled out my weekend bag

and Paul's backpack. On second thought, I grabbed a duffel bag

for the dog, too. After each round of folding clothes or packing

personal items, I went back to listen for some indication that

the storm would pass, that all this preparation would be for

nothing. I didn't hear anything like this, but my slow, methodical

movement calmed me. Right: Outside the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in downtown New Orleans. Photo by Win Henderson/FEMA. By the time Paul got back, I'd already carried the bags and the plastic file boxes I'd packed with insurance info, our marriage certificate and various other important documents out to the car. We drove away from our home with one bag of clothes each, one bag of dog supplies, a couple of bags of food and bottled water, and Molly's bed. We followed the crawling traffic across the city, working our way toward City Park and then south to Airline Highway. Usually a 15-minute drive, that day it took twice as long. We passed gas station after gas station with lines of cars waiting their turns at the pump. Some stations already had bags over their pumps -- they were selling out fast. We had taken only a few necessities, but some people seemed to be pulling everything they owned behind them in trailers and RVs. We kept listening to the radio for evacuation information. People were calling the radio station asking for alternative routes out, or shortcuts to get to family members. Just past the St. Charles Parish line, we heard some important news: The contraflow was open. This meant that all lanes of traffic on the major highways out of the New Orleans metro area, including Interstate 10, would be opened in the direction of safety. The idea was to get more people out faster and to keep them from getting back into the metro area. This only happened in very serious situations. This would not affect us on our Airline Highway route, but traffic picked up with every mile that we drove.

When we stepped up to the hotel counter over two hours later, more than one phone was ringing in the background. "Thanks for calling AmeriSuites. We are currently booked through Thursday, Sept. 1st," said the girl behind the counter. Then a minute later, "Yes, the hotel's filled up. We're booked through Thursday." Whoever was on the other line finally understood. The phone rang again, and the woman delivered her line. This time, the look on her face told us the caller hung up as soon as they heard that there were no rooms. We checked in using our online reservation number and a credit card. On Sunday afternoon, dark clouds started rolling in, and Baton Rouge took on a markedly different feel. Stores and banks had already posted signs reading, "Closed Monday due to Katrina. God bless." The shelves of bottled water and non-perishable foods were nearly wiped clean at local stores, including the Rite Aid where I tried to get a prescription filled. The pharmacy line was over an hour long, and the empty white shelves shook my nerves. I wondered whether the storm would find us here, too. When I returned, the hotel was packed. Late evacuees who couldn't find a room in this overbooked city were driving from hotel to hotel looking for accommodations, dragging along most of what they owned. A bit later, Paul found out that AmeriSuites had opened the lobby to stranded evacuees in need of a place to camp out. Every inch of space was filled with people. I stood for a moment in the midst of the madness, feeling as if I were unable to move through the throngs swirling around the lobby. A couple with a teenage son rolled in with two ice chests, a bulk box of cat litter and several bags. A very pregnant woman sprawled across one of the couches. The older woman accompanying her, probably her mother, paced back and forth saying, "You're going into labor, I'm sure of it." Students of all ages sat at café-style tables with books and binders scattered in front of them. Just getting onto the elevator proved a challenge, as hotel guests seemed to have lost all turn-taking skills. The doors would open and people on both sides would stand waiting for someone to decide who moved first. Outside, the parking lots of the hotel and two neighboring restaurants were filling up steadily. Those not fortunate enough to find space in the hotel lobby were taking up residence in their parked cars. A couple of RVs stood parked beside one another, canopies up, with people congregated between them for shelter and consolation. Children walked from the nearby King Buffet, one of the few restaurants open by that time, carrying boxes of Chinese food to eat in the car. The hotel manager and her husband were sinking the outdoor furniture to the bottom of the pool to keep it from blowing into the building as the winds picked up. It made sense, but it felt like a scene from The Twilight Zone. The rain continued from Sunday into Monday, with winds picking up over 30 miles per hour.

For better or worse, we spent most of Monday watching news coverage of Hurricane Katrina's progress and updates from New Orleans. Scenes of people trying to get into the Superdome on Sunday evening, when Mayor Nagin finally called for mandatory evacuation, played over and over again. The mayor asked those coming to the shelter to bring enough food, water and supplies for three to five days, but many showed up with nothing. An image of a young mother hoisting her toddler up to her hip but not carrying a single bag haunts me still. By 5:30 p.m., the storm had passed through Baton Rouge, and I felt compelled to get outside and see what was going on. I think in some strange way I believed I could see how the people of New Orleans were holding up against this tragedy, if I would just go outside and look. I didn't find much that looked promising. Traffic lights were out, power lines were down in some of the streets and half of a wind-blown tree blocked the entire lane in front of us as we approached a shopping plaza area. We made a stop at a Greek restaurant with an "Open" sign. As Molly and I waited outside for Paul to return with dinner, I saw a couple of kids dangling their legs out the back of an SUV. I walked Molly over, and the little boy in the back put down his ham sandwich and started walking toward us. He wanted to know if Molly would bite him, and I told him to go ahead and pet her. When I asked if he was also from New Orleans, his mother came around the side of the vehicle and asked if I'd heard any news of our home city. She'd driven with her husband and four children from New Orleans to Lafayette looking for a place to stay. They were turned away from shelters in Baton Rouge and Lafayette, and when a woman from the Lafayette tourist bureau tried to rent her family a houseboat, she decided to come back to Baton Rouge. "I've got money. I just can't find any places with rooms left. I mean, what are we supposed to do?" she asked. I didn't have an answer for her. All I could do was wish her luck and walk back to my car. That night, Paul and I debated different options for the immediate future. We could try to stay with friends in Baton Rouge, we could head toward my family in Pennsylvania or we could go to his parents' house in California. Where and when we would go were still up in the air. I suggested we wait until the next morning when more news about storm damage might be available. Tuesday's bad news made our decision clear. We would take off that morning to California, where a party celebrating our recent wedding had already been planned for that weekend. Leaving Molly in a kennel and flying from the Louis Armstrong Airport was no longer an option. If we split the 2,400 miles of driving over 4 days, we would make it to Paul's parents' house in Kneeland just in time.

Paul did most of the driving,

but I felt an urge to keep moving faster. I couldn't feel safe,

couldn't relax at all, until we reached the point where I-10

crossed the California state line. We would still have a ways

to go, but focusing on that point was all that kept me from falling

apart. I didn't know the state of our home. My workplace was

likely gone. I had no way of knowing if my friends and co-workers

were safe. The sheer uncertainty made me sick to my stomach. Left: Family members carry signs outside the Houston Astrodome shelter looking for lost relatives. Photo by Andrea Booher/FEMA. Another wave of nausea struck every time we turned on the radio. News from New Orleans seemed to be getting worse by the minute. Damage to the Superdome roof made it uninhabitable. Bodies were being dragged out of the Convention Center. Snipers shot at rescue workers as they brought the old, injured and infirm into hospitals. Looters graduated from stealing food and water to lifting tennis shoes, jewelry and computers. And still there was no food or water for those stranded in an unlivable city. Not only was the physical structure of New Orleans destroyed, but the spirit of goodwill and hospitality was being destroyed as well. Why weren't all those people evacuated to begin with? And why were there so many black faces in the crowd, and so few white? I don't believe it was because New Orleans' large, underprivileged black population was too lazy or too dumb to take responsibility for their own safety, as some would have us think. The circumstances of their generational poverty left them few options. They came to the Superdome knowing that their own homes were not stable enough to protect them. They brought little with them because they had little in their cupboards, and stores had already started to sell out and close up. They didn't get in their cars and drive away because many of them didn't have cars to hop into. For Mayor Nagin, or any other public official, calling a mandatory evacuation puts the responsibility for transferring citizens to safety squarely on one's own shoulders. Moving all of the impoverished people of New Orleans by plane, train or bus was not something the city budget was prepared for. And it wasn't just the poor who stayed: A white, two-doctorate family that we know narrowly escaped the Lake View area flood. They were airlifted out.

Since we've been here, we've only seen glimpses of normal life. The family party and a few dinner invitations by family friends have saved our sanity and reminded us that life does go on. Otherwise, we've spent our days trying to track down friends and colleagues. We've spent hours on the phone trying to reach insurance agents. We watch the news religiously in an effort to keep up with the ever-changing situation in the city of New Orleans and the progress of other evacuees. The constant change and uncertainty wears on me. I don't sleep some nights; I lie in bed picturing scenes from our evacuation, footage I've seen on television and the moments I shared with fellow New Orleanians last time I saw them in person. Every day brings new and different information. Satellite pictures and online flood maps tell us that two breaks in the London Avenue Canal dumped more than six feet of water into our neighborhood, waterlogging Paul's truck. Our insurance company totaled it without even taking a look. Another Allstate representative called a few days ago to tell us that she had tried to get into our neighborhood but was escorted out by police. She said she'd call back once she had actually seen the house. But last week brought Hurricane Rita and another evacuation. On Friday, only seconds after looking at pictures of our house taken by a friend who sneaked back in, we read the news that one of the levees in New Orleans had broken again under the pressure of Hurricane Rita's wind and rain. Who knows how long this will keep us -- and all of those people struggling to get out of shelters, find jobs and get their kids in school -- out of New Orleans? Many of the friends we'd been searching for have surfaced. Jane, a friend and former co-teacher from my days at West St. John Elementary, finally got through after weeks of calling my cell number. She is safe at home and confirmed that my former students and colleagues are okay. Other friends have passed on updates via e-mail, so that I am almost certain no one I know was hurt in the storm. Another friend and former co-worker reminded me how lucky we are again when she reached me on my sometimes-working cell phone last week. "Do you remember Michael?" Joy asked. Of course I remembered Michael, the tall, always polite and hard-working black teenager who volunteered at the Audubon Zoo's zoo camp each summer. I thought about the evening he stayed after camp to help out with a membership event. "I talked to him the other day," she continued. "He was on the roof of his house with his grandfather and 2-year-old brother for three days. They were finally rescued, and now they're in an apartment in Baton Rouge." Then I saw a different picture of Michael, fighting for his own survival and the survival of his family, waiting for someone to wake up and rescue them, something I don't think any 16-year-old should have to do. I am glad for his safety.

Right: Rebecca Bidwell-hanson wth her husband, Paul, and Molly at his parents' home in Kneeland. Photo by Bob Doran. When we first arrived here,

the big question was whether or not we'd get back to New Orleans.

Now I question whether the New Orleans I knew can ever exist

again. Will those who were forced to run from their homes not

once, but twice, have any reason to return? I think about the

three-and-a-half year chunk of my life that belongs to the Crescent

City, the Big Easy. Without planning to, I fell in love with

the children I was teaching, with the culture and personality

of the South and with the man who would become my greatest support

and husband. A little piece of my heart will always live in that

New Orleans, but the new New Orleans is a place still far off

in the distance. Rebecca Bidwell-Hanson is a former assistant editor of BabyTalk magazine. Her husband Paul, a Humboldt County native, is a professor of chemistry at the University of New Orleans.

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

We sit and watch the news together. Some reporter

is saying that the levees have been breached. We see a shot of

the Lower Ninth Ward, where many of that area's modest one-story

homes can't be seen above the waters. We watch as those who escaped

the flood walk across bridges, carrying their children and what

little possessions they can handle, seeking dry land and aid.

We look at two-story homeowners who didn't believe the floodwaters

would follow them upstairs. They peer out of attic windows or

sit huddled on their rooftops, water just a few feet below them.

We sit and watch the news together. Some reporter

is saying that the levees have been breached. We see a shot of

the Lower Ninth Ward, where many of that area's modest one-story

homes can't be seen above the waters. We watch as those who escaped

the flood walk across bridges, carrying their children and what

little possessions they can handle, seeking dry land and aid.

We look at two-story homeowners who didn't believe the floodwaters

would follow them upstairs. They peer out of attic windows or

sit huddled on their rooftops, water just a few feet below them. As

we left New Orleans on Saturday, just three days prior, there

was part of me that thought we'd be on our way back already.

But now it was evident that the voice that spoke from the pit

of my stomach, telling me we wouldn't be back so soon, was right.

We knew then that we'd have to start the next leg of our journey,

but I never imagined we'd be here in Kneeland a month after Hurricane

Katrina.

As

we left New Orleans on Saturday, just three days prior, there

was part of me that thought we'd be on our way back already.

But now it was evident that the voice that spoke from the pit

of my stomach, telling me we wouldn't be back so soon, was right.

We knew then that we'd have to start the next leg of our journey,

but I never imagined we'd be here in Kneeland a month after Hurricane

Katrina.

I am thankful beyond words for my family's safety

as well. When the water of the industrial canal poured into the

homes of the Lower Ninth Ward, I was safe and warm in a hotel

room in Baton Rouge. As parents arrived at the Astrodome in Houston

worried sick about children they'd been separated from, my husband

and I were together. And when stranded New Orleanians stood in

crowds on I-10 waiting for someone to rescue them three and four

days after the storm, we were in the arms of family 2,400 miles

away. I've got no reason to complain.

I am thankful beyond words for my family's safety

as well. When the water of the industrial canal poured into the

homes of the Lower Ninth Ward, I was safe and warm in a hotel

room in Baton Rouge. As parents arrived at the Astrodome in Houston

worried sick about children they'd been separated from, my husband

and I were together. And when stranded New Orleanians stood in

crowds on I-10 waiting for someone to rescue them three and four

days after the storm, we were in the arms of family 2,400 miles

away. I've got no reason to complain.