|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | DIRT

TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

August 24, 2006

story and photos by BOB DORAN

THE FORK MOVED ALL

ON ITS OWN. Not much, just a slight twist, but it definitely

moved. It was the summer of 2004 and I was standing in front

of the Rasta Pasta booth at Reggae on the River, eating a hot

dish of pesto. I'd left the fork stuck in the hot food while

talking with a friend. When I pulled it from the pasta I found

that the tines were warped into a claw shape. My plastic utensil

had melted from the heat of the pasta pesto.

I learned the reason why from the Whitethorn School

folks running the pasta booth: The utensils were biodegradable,

made from corn. This was explained further when I took the plate

and fork to the nearby complex of garbage cans for proper disposal.

A smiling woman sat on a stool amid the barrels

and bags dressed in rolled up jeans and a grey Reggae T-shirt

with bold letters on the back identifying her as part of the

recycling crew. Her job was to direct festivalgoers regarding

the proper disposal of their waste: cans here, plastic bottles

and cups there, glass in another barrel and so on.

She explained that the large bag marked "plates

and utensils" was destined for composting, one part of a

plan to move toward a "greener" festival. While garbage

duty was not the most glamorous job at Reggae, she was happy

to be playing a small part in making the event waste-free and

thus more ecologically sound.

aka PLA

The fork I used that day and the cups used to serve

beer and soda were made from a plastic resin, polylactic acid,

aka PLA, a  material most often

made from corn but also using other plant starches including

potatoes and wheat. material most often

made from corn but also using other plant starches including

potatoes and wheat.

Just about anyone you ask will tell you that bio-based

PLA plastics sound like a great idea. With awareness about the

relationship between petrochemicals and greenhouses gases at

an all time high (along with the cost of gasoline), people see

this new plastic derived from renewable resources as an attractive

alternative to our dependence on oil.

Add in the fact that we are getting buried by an

avalanche of plastic containers used to carry and hold this,

that and the other thing. Around 25 percent of the material in

our landfills is plastic.

The notion that bio-plastic is "biodegradable"

would also seem to be quite a plus. The people who make the stuff

certainly seem to think so. The word is embossed on the handles

of the forks and spoons used at Reggae this year.

The use of corn plastic has grown by leaps and

bounds since I first heard about it. Last year NatureWorks, a

major player in the industry (and the company that makes the

cups used at Reggae) signed a deal to supply Wal-Mart with clear

plastic containers for produce.

In a press release Wal-Mart noted that PLA plastic

will be used for 100 million containers per year and bragged

that, "with this change to packaging made from corn we will

save the equivalent of 800,000 gallons of gasoline and reduce

more than 11 million lbs. of green house gas emissions from polluting

our environment." They also pointed to PLA's "ability

to provide a price stable product as the price of oil needed

to produce conventional packaging keeps climbing higher and higher."

Could there be any downside to this picture of

an eco-groovy plastic future? A closer look into the world of

corn plastic shows that there are problems yet to be resolved.

One is a perception problem faced by the marketing

departments for corn/chemical corporations like Cargill Dow LLC,

owners of the NatureWorks brand. Targeting the ecologically-minded

can be tricky since such consumers tend to distrust mega-corporations,

particularly those who are turning broad swathes of the country

into huge factory farms covered with a genetically-engineered

mono-crop like corn.

Then there's that word -- biodegradable -- embossed

on the fork handle. What exactly does it mean? We'll get to that,

but first let's go back to Reggae.

"A Green Event"

Earlier this month, just before this year's festival

I tracked down Patty McGuire, crew leader for the food operation

feeding all Reggae volunteers. She orders "thousands of

dollars worth" of plasticware to supply the volunteers and

staff kitchens, and the dozens of nonprofit booths. Most of what

she orders comes from a company called Cereplast.

When she mentioned that "all the plastic forks,

spoons and cups are biodegradable/compostable," I asked

what that meant to her. How exactly is the stuff composted? Admitting

that she was unsure, she said, "I don't really know where

it goes after it leaves my kitchen."

In a hurry to get back to preparations for the

festival, McGuire offered the number for Cereplast for further

details.

The number led to Cereplast Vice President of Marketing

Russell Wegner, a bioplastics true believer who told me, "We're

in the resin business," as he launched into a discussion

of the potential for PLA-plastic as a substitute for almost any

type of conventional plastic -- at least within limits.

The main limit: It melts when it gets to a certain

temperature, a fact that is crucial in making it compostable.

Cereplast currently makes plastics that will tolerate up to 155

degrees. "For something to be truly biodegradable, reaching

higher temperatures tolerances is a challenge," said Wegner.

"The composters want it to break down; the consumer wants

it to hold up."

But what if the stuff gets sent to the dump instead

of a compost operation? He concedes that, "depending on

the temperature of the landfill, it could sit for a long time,"

but, he added, even if the product is not composted, "You're

still buying something that's sustainable and bio-based that

uses a renewable source versus fossil fuels."

This year's Reggae on the River was different from

years past. For one thing, the festival moved upriver to a new

site allowing more room for more people. It's safe to assume

more people meant more to recycle and more trash.

The recycling/trash system was stripped down this

year compared to the 2004 set-up. There were no garbage monitors

and no bags for utensils and leftovers, just barrels for plastic,

glass, cans and trash.

An onstage announcer declared, "This is a

green event. Virtually everything is biodegradable, compostable

or recyclable," but there was no sign that the thousands

of forks, spoons and cups coming from the food court were being

collected for composting. A look into the cans showed that the

forks and spoons went into the trashcans; the clear PLA-plastic

cups were thrown in the "plastic" barrel where they

mixed with recyclable petro-plastic water bottles.

Where

did the compost go? Where

did the compost go?

What happened to the compost collected in 2004?

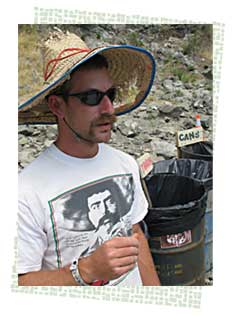

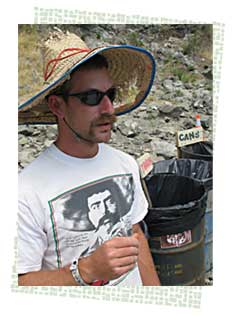

I got a hint when I ran into Ian Sigman (left) of Mattole

River Organic Farms on Bob Marley Boulevard, the main road through

the new Reggae. Sigman was leading a recycling crew, a team of

brown-shirted waste handlers who poured barrels full of bottles,

cans, plastic and trash into large plastic bags to be hauled

off on his biodiesel farm truck.

He told me of his own interest in composting Reggae

green waste. Up until 2004, he had simply amassed the vegetable

trim from the various kitchens and hauled it back to his farm

for composting. Then, as he put it, a guy named Steve Salzman

"weaseled his way in."

Salzman (no relation to political consultant Richard

Salzman) had to inform the composting crew that "some kind

of permit was needed for food waste." While Sigman was all

for "guerilla composting," Salzman had a fairly elaborate

plan for an onsite system.

Salzman is a waste management specialist who works

for Winzler and Kelly. Calling from the engineering firm's Eureka

office he explained that he'd volunteered his time in 2004 to

come up with a proposal to deal with more than just kitchen scraps,

He designed an onsite composting operation "to try to capture

the compostable paper and post-consumer scraps. And P.B. and

his crew had already ordered the compostable plastic that year

and were making all the vendors use it."

P.B. would be Paul "P.B." Bassis, one

of the main players in People Productions, producers of Reggae

-- at least until recently, when he split off to form his own

company, Infinite Entertainment. Among Infinite's clients is

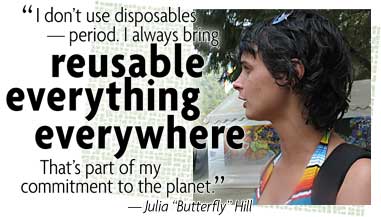

Julia "Butterfly" Hill, the world-renowned tree-sitter/environmental

activist, who, post-Luna, founded the Circle of Life Foundation.

One of Circle of Life's projects was a series of events called

We the Planet, zero-waste gatherings demonstrating the potential

for greener festivals.

W hen

I spoke with Hill at this year's Reggae and later after she was

back in the foundation office in Oakland, she allowed that she

doesn't think much of disposable plastic forks and spoons, cups

and to-go containers in general, not even those made from corn

plastic since she sees the current methods of corn production

as "out of balance" with nature. hen

I spoke with Hill at this year's Reggae and later after she was

back in the foundation office in Oakland, she allowed that she

doesn't think much of disposable plastic forks and spoons, cups

and to-go containers in general, not even those made from corn

plastic since she sees the current methods of corn production

as "out of balance" with nature.

She asks rhetorically, "Are we going to use

the toxic petroleum product that's going to go out into a landfill

and slowly and toxically break down? Or are we going to use a

plastic that comes from corn that's genetically modified and

coming from huge corporations that have no interest in taking

care of the planet or the people on it?"

Her personal solution: "I don't use disposables

-- period. I always bring reusable everything everywhere I go.

That's part of my commitment to the planet."

Circle of Life also serves as a clearinghouse for

eco-groovy festival methods through their Greening Events Guide,

which recommends many of the things instituted in the Reggae

2004 composting program: monitors at each recycling station,

onsite composting and the use of compostables, at least where

appropriate.

Salzman said he understood that by implementing

the Reggae composting plan he was "stepping on some toes,"

but he moved forward. After the food waste was gathered along

with the compostable paper, cups and utensils, it was put in

a large mixing vessel brought in by Andrew Jolin of Mad River

Compost, the company that handles green waste composting for

residents of Arcata. An elaborate aeration device was used to

blow air into what is called a "static aerated pile,"

which, said Salzman, "made it get really hot really fast,"

a key factor when it comes to breaking down PLA-plastic.

"We had pretty good success overall,"

he added. "We diverted around 50-100 yards of waste, I can't

tell you how many tons."

The corn plastic? Last time Salzman checked, "forks

and the cups and plates shriveled up and got brittle. But they

did not melt into the pile." Digging into the remains months

later he found, "distorted, weird little pieces of plastic

that were still recognizable." He noted that a mechanical

turner would break up the pieces facilitating dispersal. He was

not sure what ultimately happened to the 2004 compost, if it

was spread around the concert location or taken to some farm.

Carolyn Hawkins, solid waste LEA (local enforcement

agency) program manager for Humboldt County Division of Environmental

Health should know since the experimental composting program

was allowed under a research permit. What happened to the compost?

She's not sure either since, "They never submitted the conclusions

they were supposed to."

Andrew Dillon, top dog in Reggae recycling, knows.

The stuff ended up in the community park in Garberville. Noting

that the 2004 process was "really expensive," he explained

another reason the experiment was not repeated. The Dimmicks,

owners of the new site for Reggae, do not want onsite composting.

This year's kitchen waste? "It went to the landfill, but

it's not bad for the landfill -- it will decompose."

As to this year's corn plastic forks and spoons,

they ended up in the landfill too. The NatureWorks plastic cups

are another story.

Grocers and recyclers

I ran into Phil Ricord, owner of Wildberries Marketplace,

lounging under one of the shade tents at Reggae finishing off

a beer, which as he pointed out, was served in the same sort

of NatureWorks cup used in the smoothie bar at his store. Noting

that he likes i t

that "the cups go back into the food chain," he turned

his over and showed me what seemed to be a recycling symbol on

the bottom: a triangle of arrows with the number 7 in the middle.

What does it mean? Neither of us knew. t

that "the cups go back into the food chain," he turned

his over and showed me what seemed to be a recycling symbol on

the bottom: a triangle of arrows with the number 7 in the middle.

What does it mean? Neither of us knew.

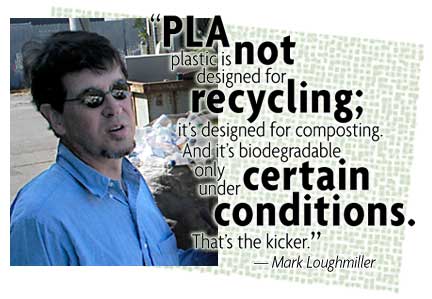

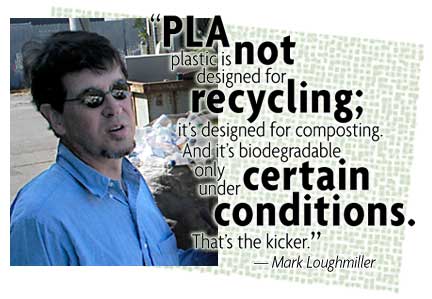

Back in Arcata I stopped by the office of Mark

Loughmiller executive director of the Arcata Recycling Center,

something of a plastics expert. He explained that the "7"

is a resin identification number denoting "other."

"That's where the recycling industry is having

an issue" with the PLA-plastic manufacturers, he contended.

He launched into a tangled history of the resin identification

system. Reduced to basics it comes down this: The triangle of

arrows does not necessarily mean the plastic can or will be reused.

No. 1 and No. 2 plastics are pretty much the only grades that

are effectively recycled. Nos. 3-7 are typically lumped together

and shipped out to plastics handlers who send them to China and

a fate unknown. (See Journal cover story June 5, 2003,

"The Problem With Plastics.")

Loughmiller thinks adding PLA in the "other"

category just confuses the consumer who falsely assumes the material

is recyclable. It is not. Once it shows up at the recycling center,

said Loughmiller, "It's trash."

Loughmiller sits on the board of directors of the

North Coast Co-ops. His advice to the Co-op: "Go with the

cheapest thing. The PLA sells at a premium, and the fact is,

the [PET] containers they're using now are recyclable. PLA plastic

is not designed for recycling; it's designed for composting.

And it's biodegradable only under certain conditions. That's

the kicker.

"They're hanging their hat on the public's

environmental desires, knowing the public is not really educated

about all of the side issues. All most people care is, `Oh, petroleum

is bad; there's an oil shortage. We need an alternative, so let's

buy this package.' When it comes down to it, it's all marketing.

You've got a company with a product that's an alternative to

petroleum, at least somewhat. They're marketing that point, but

ignoring things like the energy inputs."

"We haven't adopted corn plastic," said

Len Mayer, general manager of the Co-op. "Eco-friendly plastic

or paper is a half step. It would be great if it was a solution,

but there are still some issues. Ultimately the best thing is

for people to reuse containers, for people to bring their own

in."

Loughmiller's other concern is with the contamination

factor. Since PLA can look almost identical to recyclable plastics,

most consumers will not recognize it and will add it to their

other recycling. If a bundle sent off for processing is 2 percent

contaminant, the load will be rejected.

If you go to the Cereplast or NatureWorks website,

you'll find that there's usually an asterisk next to the word

"biodegradable." Their definition is based on guidelines

set by the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI). They'll tell

you the biopolymers will degrade in a certified "controlled

composting environment," a municipal/ industrial facility

with a digester that meets their standards. They even supply

a map showing the nearest such facility in your area. There are

none in Humboldt County.

Those plastic cups at Reggae? Since most people

saw them as "plastic" they are currently part of the

recycling material headed for Eel River Disposal & Resource

Recovery in Fortuna, the company that handles the recycled glass

and plastic for the festival. When I spoke with company president

Harry Harden last week, he had not yet picked up the Reggae recycling

and seemed unaware that the plastic collection could be a co-mingling

of No. 1 petro-plastic bottles and No. 7 corn plastic cups, but

he's not surprised.

Right: Comingled No. 1 plastic bottles

and corn plastic cups at Reggae 2006.

To the consumer, "Plastic is plastic,"

he told me. "They'll come in here and throw laundry baskets

in with the recycling.

"If [the plastics from Reggae are] not too

badly contaminated I'll just bail it altogether," he said,

"but if it's heavily contaminated, I'll have to run it across

my sorting belt and we'll hand pick it," separating the

No. 7 cups.

Harden said he would probably add the corn-plastic

cups to his "film-plastic," a mix that includes grocery

bags and the like. "We send the film plastic to San Leandro

and they process it to mix it with wood chips and make lumber

with it, decking."

According to Mark Loughmiller, the co-mingled corn

plastic will have to be removed from the recycling stream at

some point. If Harden sends it to San Leandro, it will happen

there. Putting it bluntly, Loughmiller said PLA is "trash,"

destined for the landfill.

"The Trex decking he referred is generally

made exclusively from plastic film. PLA plastic would be a contaminant.

The industry has a mechanism to separate the contaminants, but

once they do, it's garbage for them.

"My attitude is to be up front with the residents,

to tell them, `This is garbage' and make them throw it away rather

than paying the freight to send it elsewhere."

Loughmiller noted that the PLA industry made a

presentation at a recent national recycling conference and suggested

that a system be put in place so that recyclers could accept

PLA plastic. "They're argument was, `Yes it is a contaminant,

but if you collect it and send it to us, we will make sure it's

composted.' But we're not going to collect it and spend thousands

of dollars to truck it to them."

Nevertheless, when

it comes to the bottom line, Loughmiller does not seem too worried

about the impact of corn plastic because it's not as toxic as

much of the material that goes into the landfill. Nevertheless, when

it comes to the bottom line, Loughmiller does not seem too worried

about the impact of corn plastic because it's not as toxic as

much of the material that goes into the landfill.

"It has almost no weight; you can dispose

of it and it's not going to hurt a damn thing. I'd rather spend

our limited resources on getting batteries out of the waste stream

or hazardous household chemicals."

Left: Reggae 2006, biodegradable fork in the

trash.

Organic Planet

Simply from the name of the local festival coming

up in Eureka this Saturday, the Organic Planet Festival, you

have to assume the organizers are striving for sustainability.

This is the second such event sponsored by Californians for Alternatives

to Toxic Sprays "celebrating a natural and non-toxic world."

Said Patty Clary executive director of CATS, "We've

been going through hell trying to get our waste stream down.

We've been trying to do the right thing, but there are controversies

in everything you do."

For example, last year's festival followed one

of Julia Butterfly's waste reduction tips by asking people to

bring their own foodware.

"We told people to bring their own plate for

the world's largest organic salad," said Clary. "We

found out you can't do that."

After the festival the county health department

called Eureka Natural Foods, the primary sponsor of the big salad,

to let them know that the possibility of contamination made the

BYO suggestion a no-no.

Karen Sherman is the volunteer in charge of procurement

of supplies for Saturday's festival. She also works for the City

of Arcata's environmental services department, a job that includes

looking at trash generated during public events like those held

regularly on the Arcata Plaza.

"There's a new law that states [events] over

2,000 people must show what they're doing to reduce waste. So

we've been talking with event coordinators asking them to make

plans as to what they're going to do: Whether they're going to

try to go with compostable cups and dishes or what other kind

of materials they'll have, whether they'll be recycling."

Asked where the material might be composted, Sherman

suggested, "either backyard composting or at a commercial

facility," admitting she was not sure about the logistics

or about the laws regulating composting.

For the Organic Planet Festival she settled on

compostables purchased through a local company, Gess Environmental.

She says she tried to minimize use of corn PLA, "because

of the GMO-related controversy around using corn. For the most

part we went with bagasse, a material made from sugar cane. We

went with the SpudWare for our forks and spoons thus limiting

the PLA to our wine and beer."

She has arranged for volunteers like those used

at Reggae 2004 who will direct people on what item goes in which

container. "I don't want the beer and wine cups to get into

the recycling bins," she said.

While she was aware of the potential for corn plastic

contamination, she did not really know the fate of the material

used at the festival. From talking with Christine Jolin of Gess

Environmental, she assumed it would be composted. Since Christine's

husband, Andrew Jolin, is the composter who runs Mad River Compost

(and the same guy who aided in the Reggae operation), she figured

it would be composted there. It won't. It's not that he couldn't

-- legally he can't.

As Loughmiller explained, "Andrew, when he

says he can do it, he has to be speaking technically. Legally

he cannot recycle post-consumer food waste. That's one of his

big issues. He can collect the waste from prep kitchens, but

not the food left on the plate that a customer has touched. It's

a health code issue."

Hawkins, the environmental health enforcer whose

department oversees Jolin's compost operation concurred, "That

is not waste that's allowed at the [Mad River] facility under

his current operation agreement. They don't have a permit to

do food."

The composter

Andrew Jolin spent much of the last 10 years collecting

food waste, composting it and using it on his worm farm, then

the law changed and he is not allowed to do so any more. He's

still intent on seeking out a viable option for that part of

the waste stream, and for bioplastics, but says the laws make

it quite complicated.

"Because of changes in the rules, we've had

to discontinue picking up [the PLA plastic] from Wildberries

and others we were dealing with," he said. "The problem

is that we don't have an established food waste program in the

county, and because of the [small] volume we probably won't."

Jolin said he's been talking to a number of local

businesses: Robert Goodman Winery, Footprint Biodiesel, HSU and

others about collecting their bio-waste.

"We are preparing to a do a pilot project

with the city of Eureka, Arcata and HSU collecting food waste.

The Organic Planet Festival will be an advance part of that.

We'll be collecting their food waste [and compostables] to characterize

it: check for contaminants, see what volume you have."

And once it's analyzed? "It will go to the

landfill."

Jolin is obviously passionate about the importance

of composting and the potential for bioplastics. He worries that

his plans will be misunderstood.

"This is all new, cutting-edge stuff,"

he tells me as he calls for the third time in the space of an

hour. "I hate to see red flags go up on biodegradables.

The Co-op has been questioning whether they should go over. One

of the board members was saying it makes it hard on recycling

because it gets mixed in. It's not really [a contaminant for

recycling]. Down in the Bay Area the oil industry got together

with the plastic recyclers making false claims against it. With

the equipment they already use for sorting PET, you can easily

remove the PLA.

"Let's get down to what's really important

here: We can sit by and be like Ford and GM are with the hybrid

[vehicles] and be way behind, or we can embrace this new technology

and work on perfecting it. But if we just sit around and criticize

it, it just won't happen. The other option is more polystyrene,

more oil-based PET and other oil-based plastics, most of which

are not recycled and end up in landfill. Let's face it: It's

made from oil and that's the scourge of our civilization right

now. [Bioplastic] is not a perfected technology, but companies

like Cereplast and NatureWorks are putting a lot into it. No,

it's not perfect, but it's going in the right direction."

Post-script

After I spoke with Patty Clary from CATS telling

her a little bit about what I'd learned about this complex issue

she sent me an e-mail. "So, in your article, is CATS to

be made out to look like hypocrites or dupes for buying compostable

plastic?" she asked. "Actually, I feel pretty good

about what we're attempting overall with our festival, and I'm

not naïve enough to think that trying to do something won't

stir things up...."

I wrote her back to say I didn't really think of

anyone I talked with as being hypocritical on the subject of

bioplastics. Most consumers seem woefully under-informed, but

it's heartening that they are willing to try to do the right

thing. The harsh reality is this: Even if your plastic is greener,

it's still going to end up at the dump. As Harry Harden so eloquently

put it, "Plastic is plastic."

Above:Trash and recycling at Reggae on the River.

TOP

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | DIRT

TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a

letter!

© Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

material most often

made from corn but also using other plant starches including

potatoes and wheat.

material most often

made from corn but also using other plant starches including

potatoes and wheat. Where

did the compost go?

Where

did the compost go? hen

I spoke with Hill at this year's Reggae and later after she was

back in the foundation office in Oakland, she allowed that she

doesn't think much of disposable plastic forks and spoons, cups

and to-go containers in general, not even those made from corn

plastic since she sees the current methods of corn production

as "out of balance" with nature.

hen

I spoke with Hill at this year's Reggae and later after she was

back in the foundation office in Oakland, she allowed that she

doesn't think much of disposable plastic forks and spoons, cups

and to-go containers in general, not even those made from corn

plastic since she sees the current methods of corn production

as "out of balance" with nature. t

that "the cups go back into the food chain," he turned

his over and showed me what seemed to be a recycling symbol on

the bottom: a triangle of arrows with the number 7 in the middle.

What does it mean? Neither of us knew.

t

that "the cups go back into the food chain," he turned

his over and showed me what seemed to be a recycling symbol on

the bottom: a triangle of arrows with the number 7 in the middle.

What does it mean? Neither of us knew.

Nevertheless, when

it comes to the bottom line, Loughmiller does not seem too worried

about the impact of corn plastic because it's not as toxic as

much of the material that goes into the landfill.

Nevertheless, when

it comes to the bottom line, Loughmiller does not seem too worried

about the impact of corn plastic because it's not as toxic as

much of the material that goes into the landfill.