|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ART

BEAT April 20, 2006

ON MARCH 15, KRISTINE MOONEY WAS IN HER SHELTER COVE HOME. She was vacuuming. Hearing a strange sound, she turned off the vacuum and looked out the window. A man was taking his chainsaw to the cypress by her house, while another guy videotaped the work. Mooney started freaking out. She called her friends, she called her attorney, she cowered inside. She was so scared, she threw up. "I was alone," she said, later. "I was scared out of my mind." The tree-trimmer was Eric Schatz, of Schatz Tree Service. And she'd been Googling him. Mooney first met Schatz on Feb. 19. He and Eureka attorney Andy Stunich arrived in Shelter Cove, at the neighboring lot, in a "nice, brand new flatbed Ford truck," she said. It was 10 a.m., she was still in bed. She ran downstairs and let her dog out. There were two men out there. She recognized Stunich -- he represented the neighboring lot's owner, Larry Castelanelli. The other guy she didn't know. They both wore wood-cutter clothes, she said. Castelanelli sued Mooney in July 2004 over the cypress -- a massive, densely-branched, 75-year-old tree, bigger than house-sized, hairy and wild, with a canopy almost as wide as it is tall. It begins, at ground-level, snug against Mooney's home, then bends out over Castelanelli's lot. Castelanelli's suit accuses Mooney of interfering with his attempts to sell the property by declaring -- to him, to his broker, and to some potential buyers -- that because it is a lot-line tree they would need her written consent to trim it, consent she wasn't likely ever to give. The tree, she said, offers aesthetic value, and privacy. And she loves it. She countersued. When Mooney went outside to confront the two men, she and Stunich got into a "screaming match" -- her saying they couldn't cut the tree because the trial was pending, him saying they were going to cut the tree. The other guy stood quietly by. "I ran into my house, after screaming and yelling with Andy Stunich, and woke up my boyfriend," Mooney said. Her boyfriend went outside, and the guy she didn't recognize put out his hand and said, "Hi, my name is Eric Schatz." Her boyfriend "immediately withdrew his hand and said, `Eric Schatz!' And I thought, who's Eric Schatz? And my boyfriend said, `This is the asshole that gets paid thousands of dollars by Pacific Lumber to yank treesitters out of trees.'" More screaming ensued, then Mooney called the cops. Schatz, the whole while, "was very cordial, very calm," said Mooney. While they waited for the cops to arrive, he and her boyfriend ended up joking and talking about fishing. The cops came, they talked and Stunich and Schatz went away. Mooney went inside and got on the phone again. One of the people she called was Darryl Cherney, co-founder of the North Coast Earth First! and veteran forest activist. "Darryl was just flabbergasted," she said. "He said, `Do you have a computer? Google this man, see what it says.' And so I did. There were 644 hits, and I was amazed. I had no idea who he was." She encountered posts abut Schatz on websites such as Earth First!, We Save Trees, Portland Independent Media Center, SF Bay Area Indymedia and others. There were stories calling Schatz a "wife-beater," referring to court documents and alleging he'd broken a bone in his (now-ex-) wife's throat back in 1992. That he dangled screaming treesitters upside down. That he tied cords around a sitter's legs to cut off circulation. That his crew members stepped on sitters, choked them, kicked them in the ribs, threatened them. That Schatz told one treesitter that he and his crew would tell people she had "committed suicide" if she happened to fall. One treesitter he had extracted, Jeny Card -- her forest name is Remedy -- called him a "class-A abuser." "My whole perception of this man changed," Mooney said later. "He's a wolf in sheep's clothing. The man is a monster." After Schatz trimmed the cypress tree in March, she did an interview with KMUD about the experience. "After the KMUD thing," she said, "all the treesitters are talking to me. They're coming out of the woodwork."

Right: Protestors at the 2003 Freshwater tree-sit

extractions. Many of the Internet postings and articles about Schatz started appearing around then. Forest activists -- or one of their attorneys, perhaps -- obtained, and posted to the Internet, a copy of a report by a social worker with the Humboldt County Center for Child Advocacy that was based on interviews with the Schatzes, their minor children and friends. It tells a story that is more complete and less conclusive than what is found in the activists' other posts. There are no proven crimes; everybody, at one point or another, sounds like a victim. The social worker could only conclude: "Rage appears to be the family theme of the Schatz family. It has been most difficult ... to ascertain clearly where the anger falls." Pacific Lumber Co. accused as many of the treesitters it could identify of trespassing -- the criminal case on those charges ended last year and the sitters were fined. In Remedy's case the fine was $10. The civil case, The Pacific Lumber Company, and Scotia Pacific Company LLC, Plaintiff, vs. Doe 1 "Remedy"; Doe 2 "Wren"; Doe 3 "Shining Light" and Does 4-200, Defendants, is set for trial June 19. Some of the activists could be facing damages and costs up to $300,000.

Left: 2003 Freshwater tree-sit extractions.

Several have since dropped their cross-complaints, including Remedy -- Jeny Card -- who said she wanted to help keep the trial focused on "Maxxam's manipulation of this community," as she told reporters, and on Pacific Lumber Co.'s management. Among the remaining cross-complaints are ones filed by Scott Petersen and Kristi Sanchez, both represented by attorney David Kosmal. Kosmal, in an interview Friday, said Petersen, aka "Luigi," had been living in a tree for six months by the time Schatz and his crew came to get him. He was out on a traverse line, between two trees. "Mr. Schatz, after giving Luigi a real scolding, produced a pair of handcuffs and said, `Look what I have,'" said Kosmal. Peterson resisted by folding himself over his harness so Schatz couldn't unclip his safety and reclip him to one of his lines. At some point, Kosmal's client alleges, Schatz attached a rope to the chains on one of Petersen's arms, threw the line over a branch overhead, and told the ground crew to haul the line -- hoisting Petersen by the arm while his other arm was locked down in the other direction. "So he was basically stretched like that, and he was sitting there screaming in pain," Kosmal said. It lasted, he says, about 10 minutes. "And if you pull back and look at it, this is way beyond the edge -- too extreme, too on the edge."

Kosmal said that Palco, with the help of the county Sheriff's Office, had intentionally tried to terrorize his clients. "They have this kind of pattern of sending up the brute squad," he said. Right: 2003 Freshwater tree-sit extractions.

Eric Schatz is walking across the soft carpet inside the modern stucco building where Andy Stunich works with the firm Roberts, Hill, Bragg, Angell & Perlman in Eureka, heading for an upstairs conference room. He stops suddenly, leans over and puts his hand on the carpet. "C'mon girl, you'll get stepped on," he coaxes. After a moment, he stands up, and a little red ladybug is scurrying along his thumb. He opens the front door and shakes the ladybug free, then goes upstairs after Stunich. Schatz seems earnest, and patient. He never raises his voice, and the gaze of his scotch-brown eyes is direct. He's 48, trim but not skinny, with graying hair and a fluffy gray-and-white handlebar mustache. He's wearing worn work boots, jeans, and white T-shirt depicting a hand holding a fishing pole, a fisherman and fish in the background, framed by the words "Let 'em off the hook. Catch and Release." He and Stunich both says things like "heck" and, in Stunich's case, "h-e-l-l" for "hell." Yes, Schatz says, he wants to talk about the wife-beater allegations, especially since they've become a theme in some of the treesitters' depositions of him. "That's a very heinous thing to be accused of," Schatz said. "Man, it even has the connotation that you're guilty until proven innocent." And that's just the thing, he and Stunich say. In 1992, Schatz was accused, arrested, and charged with felony and misdemeanor charges of spousal/co-habitant abuse. He pled not guilty. The felony case was dismissed, and he was placed on misdemeanor diversion -- a route he says he chose instead of dragging his children through the spectacle of a trial. The diversion was a year of family violence counseling. The 14-year-old arrest, says Stunich, has been dragged into the depositions of Schatz, with Schatz questioners trying to pry information out of him about his now-grown children, such as their addresses. They also asked Schatz endless irrelevant questions, Stunich says -- it got to the point where Stunich filed a motion last month for a protective order to stop Schatz' deposition. A defining moment came when treesitter Anna Farnam asked Schatz, "Do you think it's possible to love someone and cause them physical harm?" To which Stunich interjected: "Objection. I'm suspending the deposition. It's over. Bye-bye." Attorney Jamie Flower, who represents Farnam (and Remedy), asked to stay on the record. Stunich said: "I'm not going to sit here and listen to these what-is-love questions, all right?" Stunich doesn't buy the violent-Schatz theme. And he shakes his head over the Shelter Cove tree case. "You know, there's a million people who could trim that tree," he says. "But how many people are able to not lose their temper? The guy's got an incredible talent in that regard." Schatz says the calmness, especially during treesitter extractions, feels "very natural." "I'm a problem solver, I'm a negotiator, I'm a tactician," he says. "You have to be very cerebral about this. I knew I could never let one of these people make me angry." The full videos, he and Stunich say, will exonerate him of charges of violence. "There are a ton of knuckledraggers out there who would have loved to go up there and remove those people," Stunich says. "I think Pacific Lumber showed remarkable constraint in hiring someone like Eric." But why did Schatz take on the job? He says once the treesitters began multiplying in the trees back in 2003 in Freshwater, he knew "there were going to be problems."

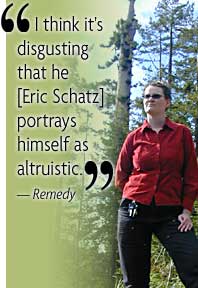

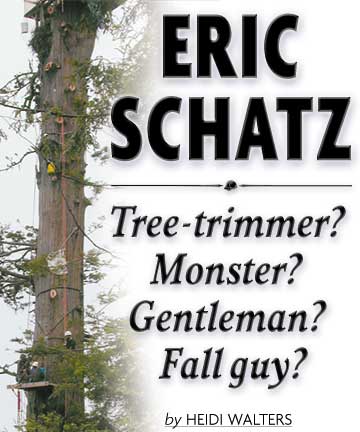

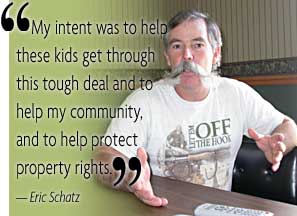

Right: Eric Schatz. Photo by Heidi Walters. Schatz warms to what has been his staunchest theme: He is rescuing these treesitters, because the longer they're up there, he says, the more likely they'll fall and get hurt or die. "I want these kids to go on and have lives, find a cure for cancer, or raise a family," Schatz says. "But don't get sucked into this manipulative, twisted group's misguided design to control other people." He had other reasons for accepting the work, as well. Schatz, who has lived in Humboldt County since he was 12, was raised by a single mother. He went to work in the woods when he was 15. "I kind of feel like I built myself out of spare parts, modeling myself after people I found worthy of liking." He calls himself a "wannabe-Christian" -- his belief, he says, is a bit of a work in progress. But he talks a lot about being a good citizen. "My intent was to help these kids get through this tough deal -- and to help my community, and to help protect property rights," he says. "It's a many-fold thing. I believe that as a person of society, as a community member, a taxpayer, a friend and a neighbor, that we have an obligation that when someone is in need, we need to help." Schatz says he understands that the treesitters have a cause. "I empathize, I'm driven to help 'em," he says. "And everybody's entitled to their opinion, to want to go out and save the world. But they should not do it in an unsafe manner. And whose politics are so saintly they can sidestep the law?" Treesitting, he says, doesn't qualify as civil disobedience. "For them, it's their holy war," he says. "They've blatantly called themselves warriors." The treesitters, likewise, accuse him of being a warrior of Pacific Lumber Co. Or a pawn. Eric Schimps, who was one of several independent observers monitoring the treesit extractions back in 2003, reflects that "corporations are very good at this. They know how to protect themselves, and to put some fall guy out there to take the heat." Schatz objects to the characterization. "I'm not Palco's extension," Schatz says. "I'm not their corporate thug. I'm not anything like that. I am Eric Schatz, Schatz Tree Service, Incorporated. The timber company was simply my client." Schatz says he's had treesitters drop liquids on him. He's been called nasty things in public and on the web. He's gotten hate mail. Convicted arsonist Rodney Coronado, affiliated with Animal Liberation Front actions, came to his house and also posted Schatz' home address and phone number on the web. And they don't mention the time, adds Stunich, that Schatz arrived at Anna Farnam's tree the same time as the pizza delivery guy -- Schatz paid for the pizza and brought it on up. They don't mention the time he rescued a stranded treesitter in the Mattole who was yelling for help. But Schatz seems miffed especially at the accusations coming from Remedy. In Schatz's video, the interaction between him and Remedy seems cordial throughout. There's even some banter. Remedy calmly refuses to come out of the tree voluntarily, so Schatz and his crew go about figuring how to remove her. Her arms are inside a "lockbox" -- a contraption of two metal tubes, welded at an angle, with a pin inside that joins the chainlinks on her wrists. If she pulls the pin, her arms come out. If she doesn't, Schatz and his crew have to saw the tip off the pointed end where the lockbox bends, or cut the branch and lower it with her. She doesn't pull the pin, but remains calm. Eventually, though, her arms relax so that the chainlinks are revealed -- enough so that they can be snipped. She repeats her message that she wants them to stop clearcutting the forest. They chat about Julia "Butterfly" Hill, the most famous treesitter of them all. "She called me today," says Remedy. And, a few moments later, "She's pretty concerned." Schatz assures her that he's been climbing 27 years and that he and his crew were "trained six ways from Sunday." She asks that, when he does lower her down, he not put handcuffs on her. He promises he won't. "I've had dreams about you, you know," says Remedy at one point. "Was I an evil, mean creature in your dream?" he asks. "No. No. No, it was real interesting. The first dream I had, you were coming up and, you just came up on my platform and I was like, `Hi. Thanks for coming,' and you were like, `Oh, yeah, sure.' And I showed you around the tree and you thought the tree was really beautiful." "Oh, it is," says Schatz. "Because it is," says Remedy. "It is," says Schatz. "And I said, `Are you going to chase me around the branches?' And you said, `No, that would be very dangerous.'" "I'm even safe in the dream," says Schatz. "Yeah," says Remedy. Awhile later, still in the tree, Schatz says, "Thank you very much for being easy to get along with." "Thank you," Remedy replies. "Makes it easier, doesn't it?" "Yes, it does," he says. "It does. I think you've got a lot of class." "Thanks," she says. Right: Remedy (Jeny Card). Photo by Heidi Walters. "And then," says Schatz, turning off the video inside Stunich's office, "when she gets to the ground she says she was abused, and assaulted and that I was reckless." She also obtained some of his video footage of transactions and made a video, "Struggle in the Woods; Views of Extraction," and distributed it on the web. Schatz says it manipulates his footage in a misleading way and turns it into propaganda for Earth First! And then there was Kristi Sanchez's extraction. Schatz had brought Remedy down from the tree "Jerry" on March 17, 2003. Sanchez then climbed into Jerry, and Schatz went after her a few days later. She climbed away, and up, from Schatz. And out onto a brittle limb. Schatz says at one point he almost started bawling, he was so scared she would fall. She was 21 at the time, but Schatz says she looked much younger. The transcript of that video reveals long, cajoling speeches by Schatz, intermixed with comments from Sanchez. He tells her repeatedly that the limb won't hold her. She says she's not coming down, talks about the corporation. He promises her, "Listen, I could get you out of this tree and they wouldn't even charge you ... I'll get anything cleared that way." He keeps talking, cajoling, saying anything to coax her in. Sanchez says: "How about this? How about you just sit there and talk to me and then go down and you'll still get paid for your hours." Schatz says, no, he needs to get her down for her own safety. Not long after, the word "suicide" comes up. One of his crew, Jesse Bawcum, says: "You know, Eric, you go up there and she would have to commit suicide --" Schatz: "Right." Bawcum: "-- and she's not going to do that." Schatz: "Well, see, here's the thing is. They won't knowingly commit suicide; but what they do is, they back out on those limbs not understanding that it will break." The talk goes on and on. Schatz tells Sanchez of the other ways she could fight the timber company. She could join forces with others, petition for money, buy the trees. He returns to the incredible danger she's in. He tells her about his training, how it's the same kind firefighters get and law enforcement and so on. "Please, for God's sake, let me make you safe, please. Please. I'm scared sick for you guys," he says. He tells her how he fell once, when he was a young man working for a logging company. "I'm lucky to have my life." He gets closer, at long last, and begins rigging safety lines and harness. She says: "Thank you for being nice and not mean." "You guys are precious souls," Schatz replies. "I mean, everybody deserves to get through this." Schatz attaches safety lines to her, including one of his own. It takes awhile. He tells her he won't put handcuffs on her. "Can you rappel me right down through that beautiful little fern garden so I can just see it one last time?" Sanchez asks, after awhile. "Yeah," says Schatz. "And that little hump that's a U-shape?" she adds. "Well," Schatz says, `I'll tell you what. We'll take you around." The ground crew could wait, he said, while she had a long, last look at Jerry the tree. She asks if she can keep some of his gear. She mentions the view. She asks if she can watch that hawk, first, before being lowered down. Schatz says, "Trees are an emotional issue, aren't they?" Sanchez replies: "To me, they're the perfect being." Schatz: "Well, I think people are." On a half-sunny late afternoon this April, Jeny Card stands on the side of the road, looking at the tree Jerry from a distance -- she's under injunction to stay off PL land. Jerry towers above scruffy undergrowth and smaller trees in an airy space overlooking a steep slope. There were more trees here in 2003, but the timber harvest progressed -- large patches of clearcut swipe the landscape. Jerry has no limbs. It's a knobby, tapered, 180-foot pole with a particularly large, club-like bulge of big-limb stumps about two-thirds of the way up. Oddly, that makes it look a bit like the Earth First! symbol of a raised fist. After the extractions, Schatz de-limbed Jerry hoping to deter other treesitters. It didn't work, so he took off more limbs. And in the end, Pacific Lumber decided not to cut Jerry down -- the company decided it wasn't worth logging, apparently because of the way it's situated with a steep drop to one side and the road to the other -- it would likely break into unusable pieces upon felling. Fuzzy, short, green fronds are starting to sprout in its upper reaches. "I don't come up here very often," Remedy says. "It's actually great to see Jerry recovering. All that growth is new." Remedy spent 361 days in Jerry, with her cell phone, conducting a well-researched campaign to save the Freshwater forest. She says it's hard to say exactly what she felt when she saw Schatz climbing up to get her that day in 2003. She knows she decided "it would be crazy to fight with three men in a tree," and so she was compliant. But she maintains her stance that all of the extractions were violent, regardless of whether anyone was hurt. They were done against someone's will. She says Schatz is a "good bullshitter," and that his tapes might have been edited. "Someone's investigating that now," she says. Remedy says he would turn into a different, less polite man when the camera was off. "I think it's disgusting that he portrays himself as altruistic," she says. When the trial comes, on June 19, both sides will have a chance to make their case. For Pacific Lumber, the question is what did the treesitters do to their business? In the treesitter's case: Who is Eric Schatz? This story has been corrected from the original printed version.

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS | ART

BEAT Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Most of Schatz's battles with forest activists

date back to 2003, during the last frenzied days of the Freshwater

treesits. That spring, Pacific Lumber's controversial timber

harvest plan to log a unit of trees along Greenwood Heights Road

was approved, amid unanswered questions about flooding in the

Freshwater watershed suspected by many to be caused by logging

and related silting of Freshwater Creek. The treesitters multiplied,

although one of them, Remedy, had already been up in a tree named

Jerry (after singer Garcia) for the better part of a year. Schatz,

contracted by Pacific Lumber to bring them down, climbed after

them in March and April with a crew of fellow climbers and a

videocamera hidden in his helmet. And when it was all over --

after the drama of the extractions, the media blitz, the celebrity

visitations, the wolf howls, the whoops and the yells subsided

-- the battle moved into the courtroom.

Most of Schatz's battles with forest activists

date back to 2003, during the last frenzied days of the Freshwater

treesits. That spring, Pacific Lumber's controversial timber

harvest plan to log a unit of trees along Greenwood Heights Road

was approved, amid unanswered questions about flooding in the

Freshwater watershed suspected by many to be caused by logging

and related silting of Freshwater Creek. The treesitters multiplied,

although one of them, Remedy, had already been up in a tree named

Jerry (after singer Garcia) for the better part of a year. Schatz,

contracted by Pacific Lumber to bring them down, climbed after

them in March and April with a crew of fellow climbers and a

videocamera hidden in his helmet. And when it was all over --

after the drama of the extractions, the media blitz, the celebrity

visitations, the wolf howls, the whoops and the yells subsided

-- the battle moved into the courtroom. Seven

treesitter defendants filed cross-complaints against Eric Schatz,

his tree service, his climbing crew members and the Pacific Lumber

Co. and its subsidiary, Scotia Pacific. Among their allegations:

assault, battery, kidnapping, negligence to hire, statutory invasion

of privacy, deprivation of constitutional rights and intentional

infliction of emotional distress.

Seven

treesitter defendants filed cross-complaints against Eric Schatz,

his tree service, his climbing crew members and the Pacific Lumber

Co. and its subsidiary, Scotia Pacific. Among their allegations:

assault, battery, kidnapping, negligence to hire, statutory invasion

of privacy, deprivation of constitutional rights and intentional

infliction of emotional distress. His

client Sanchez free-climbed -- no harness, no ropes -- to the

top of the tree Jerry and went out on a limb so brittle that

everyone feared she would fall. She did it, said Kosmal, because

she was terrified of Schatz, who was climbing up to get her.

Sanchez has also said that Schatz told her that if she fell,

he and his crew would say she had committed suicide.

His

client Sanchez free-climbed -- no harness, no ropes -- to the

top of the tree Jerry and went out on a limb so brittle that

everyone feared she would fall. She did it, said Kosmal, because

she was terrified of Schatz, who was climbing up to get her.

Sanchez has also said that Schatz told her that if she fell,

he and his crew would say she had committed suicide. "I

couldn't sit by and watch some young person make an emotional

decision, being egged on by some professional agitators -- you

know, these extremists come in, from Earth First!, and egg these

kids on," Schatz says. "You get these kids that are

traveling around, riding their thumb, you know, traveling with

the wind, and then they come in and all of a sudden they become

these icons, these heroes, because they're talked into going

up trees. Well, the next thing you know, they're crossing traverse

lines and using substandard gear."

"I

couldn't sit by and watch some young person make an emotional

decision, being egged on by some professional agitators -- you

know, these extremists come in, from Earth First!, and egg these

kids on," Schatz says. "You get these kids that are

traveling around, riding their thumb, you know, traveling with

the wind, and then they come in and all of a sudden they become

these icons, these heroes, because they're talked into going

up trees. Well, the next thing you know, they're crossing traverse

lines and using substandard gear."