|

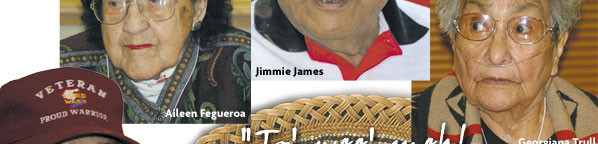

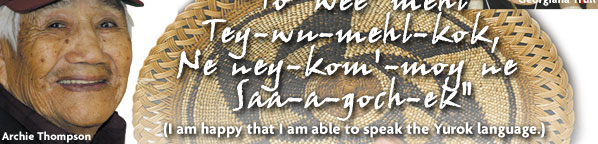

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | ARTBEAT | FOOD | THE HUM | CALENDAR January 12, 2006by HANK SIMS THIS IS HOW IT USED TO BE. For no one knows how long -- at least 700 years, probably many more, maybe back as far as the creation of the world -- all the people who lived between Little River and the Klamath River on the coast, and inland up the Klamath to Weitchpec, were Yurok, and they spoke their own language. Having been born of the area, the language was minutely attuned to the landscape and the seasons, so that the very words and sentences reflected the rhythm of the place By 1950 -- 100 years after settlers began arriving at the North Coast of California in great numbers -- the Yurok language was all but gone, as were the languages indigenous to Humboldt County: Hupa, Wiyot, Tolowa, Karuk, Mattole and Chilula, among others. The children of the Yurok were taken away from their families and sent to boarding schools, where they were beaten for using their native tongue. Parents spoke English to their children when they came home, and grandparents got old and passed away. People were made to feel ashamed of their language. It dwindled away almost to nothing. But a couple of weeks ago, when Archie Thompson arrived in Arcata a little bit late to a meeting and spotted Jimmie James, the two men, both in their nineties, joyously clasped hands and suddenly the old language was pouring out of them, each strange syllable following unhurriedly upon the last. They spoke with the unconscious confidence that people have when expressing themselves in their first language -- the confidence that is the most difficult thing to acquire when learning someone else's. For a moment, listening to them, you could almost imagine what it used to sound like hundreds of years ago, up the coast and along the lower Klamath. Few of the 35 or so people who were attending that day's strategy session at Potawot Village, which had been convened by the Yurok Elder Wisdom Preservation Project, would have been able to understand precisely what Thompson and James said to each other in their greeting. They'd all heard such conversations before, between two people who'd grown up with the language, and even the best speakers among them knew that they had a long way to go before approaching Thompson's and James' fluency. And no one objected -- no one would dare object -- when, for the second time that day, James hijacked the microphone to gently admonish the assembled students of the Yurok language, most of them the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the people of his generation. A kindly gentleman with a sharp sense of humor, James told them that the Yurok they spoke just didn't have the "ring" of the language that the old Indians spoke. "All of us here, we know how to talk, and we know what it sounds like," he said, indicating himself, Thompson, Aileen Figueroa and Georgiana Trull, the four elders who were able to attend the strategy session. "I hope I'm not discouraging you, but what you need to get hold of is the real word, and what the language really means." The words were mostly there, but the younger generation was missing the most important aspect of the language: its soul. "You got to speak it good and strong," James continued a moment later. "There's a lot of you folks out there interested in learning. But it ain't getting to you. And it's our fault. And it's your fault." What James was saying, everybody already knew it. But it helped them to hear it again, from the mouth of a respected elder. Because all of the people there were determined, from those who have been studying Yurok for 20 years to the high school students who have just started to pick up the language. They made a promise to themselves, to their elders and to the generations to come. They're going to bring it back. James' words served as a reminder that more was at stake than grammar lessons, and it made them want to work harder. Kathleen Vigil, a 62-year-old resident of Westhaven, founded the Yurok Elder Wisdom Preservation Project a couple of years ago because she knew that time was running short. Vigil is the daughter of Aileen Figueroa, one of the oldest members of the Yurok Tribe and a master speaker of the language. The project was born of a terrible realization -- that people of her mother's generation, the last generation to have any contact with the old Yurok ways, would not be around forever.

Figueroa is one of the Yurok people's treasure troves of information, of the old stories and history of the tribe. But most important to her mother's heart, Vigil said, was the language. The idea that the language would someday die with her and the few surviving speakers was a great weight on Figueroa's heart, Vigil said. And the language preservation programs in place at the time weren't doing enough, Vigil felt. People weren't learning quickly enough. Not enough people were prepared to devote the amount of time necessary to truly understand it. Classes would cover the basics, then people would drop out. The elders would have to start over with a whole new class, once again teaching students how to say hello, goodbye, man, woman. "The language would get at a point, and it would stop and no one would do anything with it anymore," Vigil said. "It was like -- we don't want to hurt your feelings."

Left: The board of the Yurok Elder Wisdom Preservation

Project, from left to right: Will Einman, Kathleen Vigil, Lawrence

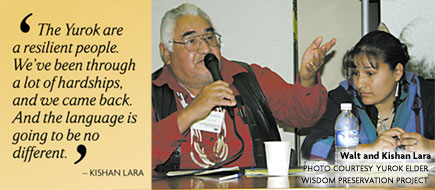

Williams, Wendy Kull and Leo Canez. Leo Canez, a 30-year-old Eureka resident and a special projects coordinator for the Arcata-based Seventh Generation Fund, now sits on the board of the Elder Wisdom Preservation Project and helped organize and coordinate the language strategy session at Potawot Village. He had his own tale to tell about how he came to realize that he had to work to restore the language. A little over a year ago, he was talking with Georgiana Trull --of the elders who attended the strategy session -- and telling her all the things that he was involved with in his work with the Seventh Generation Fund. He was telling her about the interesting, empowering work that various Native American groups were doing around the country, and how he felt honored to play some role supporting their efforts. Trull was nonplussed, he said. Instead, she pointed at him and said, "And what are you doing for your people?" Canez has a name for this type of moment. He calls it "The Elder Hammer." A few weeks later, he said, he was sitting around with some friends. There were a few elders at the table, and they began talking to each other in the old language. As Canez tells it, he and his friends all looked at each other, and they all had the same thought: Why can't we understand what they are saying? That's when he decided to attend language classes, and to devote himself to bringing Yurok back. Early on in the strategy session, 26-year-old Kishan Lara, who is taking her doctorate in linguistics and education at Arizona State University, told everyone that there are people out there, respected linguists, who are saying that Yurok is already an all-but-dead language, that it will be gone in 10 years, when most of the people who grew up with it will be gone. But Lara only brought up what these linguists had to say because she was sure they were wrong.

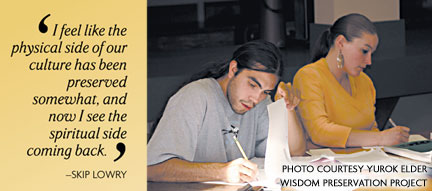

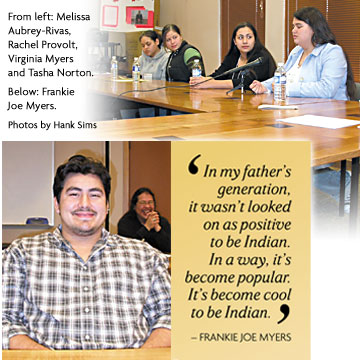

Maybe half of the people at the two-day Potawot Village strategy session were around Lara's age, and all of them were as determined as she was. Many of the young people in the room studied at the several weekly community classes held around the Yurok Reservation and in Arcata. Some of them -- teenagers or recent high school graduates -- had studied at Hoopa High School, where Yurok has been offered as a "foreign language" option for a few years now. Others were students at the brand-new American Indian Academy charter school in McKinleyville, where Figueroa and Vigil lead a daily class in the language for students. At the meeting, many of the young speakers talked about what the language has given them in the time they've been studying it. Skip Lowry, a 25-year-old who does work at the reconstructed Su'meg Village, a Yurok site in present-day Patrick's Point State Park, said that he has found it easier to pray once he became able to do so in Yurok. "I feel like the physical side of our culture has been preserved somewhat, and now I see the spiritual side coming back," he said. One of Georgiana Trull's grandsons, 25-year-old Frankie Joe Myers, said that one of the positive things about living in this day and age is the wider American culture no longer pressures people to give up their roots, as it did in the past. "In my father's generation, it wasn't looked on as positive to be Indian," he said. "In a way, it's become popular. It's become cool to be Indian." Learning the language went along with the rebirth of traditional dances -- the Brush Dance, the World Renewal Ceremony -- over the past few decades, and these ceremonies, together with the language, strengthened his identity as a Yurok, he said.

Part of the problem, everyone realized, was that too often they were still thinking in English then translating their thoughts into Yurok. That, plus the fact that few people had been able to accurately capture the rhythm of their elders' speech. Carole Lewis, a 54-year-old Hoopa resident who has been studying the language for some 20 years, apologized to the elders present on behalf of everyone. "I can see the sorrow they have for their language, because in a way we're murdering it." She exhorted her fellow students, those just starting out, to listen more closely to the audio recordings made by the elders. "We're going to lose some of it anyway," she said "but if we don't pay attention we're going to lose a lot more." But like almost everyone there, Kishan Lara remained confident. "The Yurok are a resilient people," she said. "We've been through a lot of hardships, and we came back. And the language is going to be no different." From the Yurok point of view, the language has

always been there -- it was given to the people by the Creator,

along with the Yurok lands. That's what the old stories teach,

and any questions are pretty much settled there. Although linguists

and anthropologists not brought up in the Yurok tradition raise

a number of interesting questions about where the language came

from, they don't have a much better answer ab Like Wiyot, the language of the people that lived around Humboldt Bay, Yurok belongs to a family of Native American languages called "Algic" languages, meaning they are distantly related to certain languages of the Midwest, such as Cheyenne, Blackfoot and Cree, and to others of the Northeast, like Massachusett, Micmac and Narragansett. But Yurok and Wiyot are the only Algic languages spoken west of the Rocky Mountains -- the myriad other languages spoken in the West before contact belong to some other language family, or, like Karuk, have no apparent relation to any other language at all. The academics are not exactly sure how a language from the east came to be spoken in coastal northern California. But throughout the centuries, the language clearly became deeply intertwined with this land. A couple of days after the strategy session, Canez gave an example. There are two different Yurok words to describe dogwood -- one used when the plant is in bloom, the other when it is not. The words sound nothing alike. But encoded within the words is a small story about the natural systems in which the Yurok lived. By the time the dogwood bloomed each year, Canez said, the great green sturgeon that still inhabit pockets of the Klamath were no longer in the river. That meant it was safe to swim without fear of ripping yourself open on the gigantic creature's ferocious spikes.

There's also the mechanical difficulty common to any attempt to learn a second language: Teaching your mouth to make sounds it is not accustomed to making. For English speakers, this is infinitely harder with Yurok than it is with any other European language. Yurok is filled with noises difficult for an ear used to English to understand. It contains glottal stops --made with the throat rather than the mouth. It contains an unusual vowel, sort of a cross between a short "o" and the consonant "r." One sound, written as "hl," has no close equivalent in English; instructional materials advise a student to place their tongues at the roof of the mouths, then exhale around both sides of the tongue. But even with these impediments, Yurok isn't as poorly off as many other native Californian languages. First and foremost, students can still draw upon elders who have known the language from birth. The Yurok community can work together with Hoopa and Karuk people, both of whom have active language preservation projects. The UC Berkeley Department of Linguistics has long conducted studies in the language, and is making its material available to students of the language. And the Yurok have a small corps of people -- Canez mentioned Carole Lewis and Leroy Halbe of Weitchpec, both in their middle years -- who are on the verge of becoming the next generation's master speakers. In the coming years, the Yurok Elder Wisdom Preservation Project hopes to develop a standard lesson plan for new students in the language, to get more people to attend community classes in the language and to institute an annual summer immersion camp for students, in which only Yurok would be spoken. And the leaders of the project want to continue to record the speech and stories of the elder generation, while they still have time.

"Everyone knows the Spanish words uno, dos, tres, hola, adios. Yuroks know them too," he said. "Why doesn't everyone around here know the Yurok words for those? Where we are now, we can bring that back." The first word you learn in any language class is "hello." In Yurok, the word is aiy-yu-kwee'. COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | ARTBEAT | FOOD | THE HUM | CALENDAR Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

"There

was a gathering in Klamath for the Yurok language, and a cry

came out," Vigil said last week. "My mother was 91

or 92 at that time, and we really needed to do some documentation

on her."

"There

was a gathering in Klamath for the Yurok language, and a cry

came out," Vigil said last week. "My mother was 91

or 92 at that time, and we really needed to do some documentation

on her." Vigil

decided that the passing of the language to the younger generation

needed to be intensified --more people needed to devote more

time to language preservation, and they needed to study it more

deeply.

Vigil

decided that the passing of the language to the younger generation

needed to be intensified --more people needed to devote more

time to language preservation, and they needed to study it more

deeply. "People

are going to be speaking this language out in the community in

10 years," she said. "And I hope Aileen and Jimmie

know this, because it is our promise to them."

"People

are going to be speaking this language out in the community in

10 years," she said. "And I hope Aileen and Jimmie

know this, because it is our promise to them." But

many of the young people also talked realistically about their

frustrations in learning Yurok. Virginia Myers, Frankie Joe's

sister, recently took a semester off from her studies at UCLA

to care for her grandmother and to study the language with her.

Myers said that she originally thought that after three months

or so, she would be reasonably fluent. In fact, it is taking

much longer than that. As Virginia recounted to the group, Trull

would at times become frustrated with her granddaughter, telling

her, "You're not thinking Indian! You've got to think Indian!"

But

many of the young people also talked realistically about their

frustrations in learning Yurok. Virginia Myers, Frankie Joe's

sister, recently took a semester off from her studies at UCLA

to care for her grandmother and to study the language with her.

Myers said that she originally thought that after three months

or so, she would be reasonably fluent. In fact, it is taking

much longer than that. As Virginia recounted to the group, Trull

would at times become frustrated with her granddaughter, telling

her, "You're not thinking Indian! You've got to think Indian!" out

how it got to the North Coast.

out

how it got to the North Coast. This

is perhaps the greatest hurdle that young Yurok speakers face

in their efforts to reclaim the language -- the need to understand

not just the words that make up the language, but how to "think

Indian" in a way that the language makes sense. ("You

say a word, and it doesn't mean what it means in English,"

someone noted at the strategy session. "It means more.")

This

is perhaps the greatest hurdle that young Yurok speakers face

in their efforts to reclaim the language -- the need to understand

not just the words that make up the language, but how to "think

Indian" in a way that the language makes sense. ("You

say a word, and it doesn't mean what it means in English,"

someone noted at the strategy session. "It means more.") Canez

takes courage in the way that groups of dedicated individuals

devoted to other indigenous tongues, such as Hawaiian, have been

able to pull their languages back from the brink. These days,

Hawaiian is taught in schools around the state and a growing

number of people are speaking it fluently. And even non-indigenous

Hawaiians have adopted bits and pieces of the language, giving

Hawaiian English a regional flavor that grounds it to the islands.

Canez thinks something similar could happen here.

Canez

takes courage in the way that groups of dedicated individuals

devoted to other indigenous tongues, such as Hawaiian, have been

able to pull their languages back from the brink. These days,

Hawaiian is taught in schools around the state and a growing

number of people are speaking it fluently. And even non-indigenous

Hawaiians have adopted bits and pieces of the language, giving

Hawaiian English a regional flavor that grounds it to the islands.

Canez thinks something similar could happen here.